The European badger is a powerfully built black, white, brown and grey animal with a small head, a stocky body, small black eyes and short tail. Its weight varies, being 7–13 kg (15–29 lb) in spring but building up to 15–17 kg (33–37 lb) in autumn before the winter sleep period. It is nocturnal and is a social, burrowing animal that sleeps during the day in one of several setts in its territorial range. These burrows, which may house several badger families, have extensive systems of underground passages and chambers and have multiple entrances. Some setts have been in use for decades. Badgers are very fussy over the cleanliness of their burrow, carrying in fresh bedding and removing soiled material, and they defecate in latrines strategically situated around their territory.

Though classified as a carnivore, the European badger feeds on a wide variety of plant and animal foods. The diet consists mainly of earthworms, large insects, small mammals, carrion, cereals and root tubers. Litters of up to five cubs are produced in spring. The young are weaned a few months later but usually remain within the family group. The European badger has been known to share its burrow with other species such as rabbits, red foxes and raccoon dogs, but it can be ferocious when provoked, a trait which has been exploited in the now illegal blood sport of badger-baiting. The spread of bovine tuberculosis has been attributed to badgers, however, studies in 2016 conclude that the issue is more to do with cattle and farm management.[4]

Nomenclature

The source of the word "badger" is uncertain. The Oxford English Dictionary states it probably derives from "badge" + -ard, referring to the white mark borne like a badge on its forehead, and may date to the early sixteenth century.[5] The French word bêcheur (digger) has also been suggested as a source.[6] A male badger is a boar, a female is a sow, and a young badger is a cub. A badger's home is called a sett.[7] Badger colonies are often called clans.

The far older name "brock" (Old English: brocc), (Scots: brock) is a Celtic loanword (cf. Gaelic broc and Welsh broch, from Proto-Celtic *brokko) meaning "grey".[5] The Proto-Germanic term was *þahsu- (cf. German Dachs, Dutch das, Norwegian svin-toks; Early Modern English: dasse), probably from the PIE root *tek'- "to construct," so the badger would have been named after its digging of setts (tunnels); the Germanic term *þahsu- became taxus or taxō, -ōnis in Latin glosses, replacing mēlēs ("marten" or "badger"),[8] and from these words the common Romance terms for the animal evolved (Italian tasso, French tesson/taisson/tasson—now blaireau is more common—, Catalan toixó, Spanish tejón, Portuguese texugo).[9]

Until the mid-18th century, European badgers were variously known in English as 'brock', 'pate', 'grey' and 'bawson'. The name "bawson" is derived from "bawsened", which refers to something striped with white. "Pate" is a local name which was once popular in northern England. The name "badget" was once common, but restricted to Norfolk, while "earth dog" was used in southern Ireland.[10] The badger is commonly referred to in Welsh as a "mochyn daear" (earth pig). [11]

Origin

The species likely evolved from the Chinese Meles thorali of the early Pleistocene. The modern species originated during the early Middle Pleistocene, with fossil sites occurring in Episcopia, Grombasek, Süssenborn, Hundsheim, Erpfingen, Koneprusy, Mosbach 2, and Stránská Skála. A comparison between fossil and living specimens shows a marked progressive adaptation to omnivory, namely in the increase in the molars' surface areas and the modification of the carnassials. Occasionally, badger bones may be discovered in strata from much earlier dates, due to the burrowing habits of the animal.[12][13]

Subspecies

As of 2005,[14] eight subspecies are recognised.| [hide]Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common badger Meles meles meles  |

Linnaeus, 1758 | A large subspecies with a strongly developed sagittal crest, it has a soft pelage and relatively dense underfur. The back has a relatively pure silvery-grey tone, while the main tone of the head is pure white. The dark stripes are wide and black, while the white fields fully extend along the upper and lateral parts of the neck. It can weigh up to 20–24 kg in autumn, with some specimens attaining even larger sizes.[15] | All Europe, save for Rhodes, Crete and Spain. Its eastern range encompasses the European area of the former Soviet Union eastward to the Volga, Crimea, Ciscaucasia, and the northern Caucasus | alba (Gmelin, 1788) britannicus (Satunin, 1905) caninus (Billberg, 1827) caucasicus (Ognev, 1926) communis (Billberg, 1827) danicus (Degerbøl, 1933) europaeus (Desmarest, 1816) maculata (Gmelin, 1788) tauricus (Ognev, 1926) taxus (Boddaert, 1785) typicus (Barrett-Hamilton, 1899) vulgaris (Tiedemann, 1808) |

| Cretan badger Meles meles arcalus  |

Miller, 1907 | Crete | ||

| Trans-Caucasian badger Meles meles canascens  |

Blanford, 1875 | A small subspecies with a dirty-greyish back with brown highlights, its head is identical to Meles m. meles, though with weaker crests, and its upper molars are elongated in a similar way to the Asian badger[16] | Transcaucasia, Kopet Dag, Turkmenia, Iran, Afghanistan and possibly Asia Minor | minor (Satunin, 1905) ponticus (Blackler, 1916) |

| Kizlyar badger Meles meles heptneri |

Ognev, 1931 | A large subspecies, it exhibits several traits of the Asian badger, namely its very pale, dull, dirty-greyish-ocherous colour and narrow head stripes.[16] | Steppe region of northeastern Ciscaucasia, the Kalmytsk steppes and the Volga delta | |

| Iberian badger Meles meles marianensis |

Graells, 1897 | Iberian Peninsula | mediterraneus (Barrett-Hamilton, 1899) | |

| Norwegian badger Meles meles milleri  |

Baryshnikov, Puzachenko and Abramov, 2003 | A small subspecies | South-west Norway | |

| Rhodes badger Meles meles rhodius |

Festa, 1914 | Rhodes | ||

| Fergana badger Meles meles severzovi |

Heptner, 1940 | A small subspecies with a relatively pure, silvery-grey back with no yellow sheen. The head stripes are wide and occupy the whole ear. Its skull exhibits several features which are transitory between the Asian and European badger[16] | Right tributary region of the Panj River, the upper Amu Darya, Pamiro-Alay system, the Fergana Valley and its adjoining southern and mountains | bokharensis (Petrov,1953) |

Description

A European badger skeleton at the Royal Veterinary College

Dentition

Skull

Badger skin - the contrasting markings of the fur serve to warn off

attackers rather than camouflage, as they are conspicuous at night.[31]

| Dentition |

|---|

| 3.1.3.1 |

| 3.1.4.2 |

Fur

Mounted erythristic badger

Behaviour

Social and territorial behaviours

Badgers' scratching-tree

Two European badgers mutually grooming

A badger's claws

Grunting and snuffling sounds

Reproduction and development

Badger with cubs

The average litter consists of one to five cubs.[45] Although many cubs are sired by resident males, up to 54% can be fathered by boars from different colonies.[40] Dominant sows may kill the cubs of subordinates.[43] Cubs are born pink, with greyish, silvery fur and fused eyelids. Neonatal badgers are 12 cm (5 in) in body length on average and weigh 75 to 132 grams (2.6 to 4.7 oz), with cubs from large litters being smaller.[45] By three to five days, their claws become pigmented, and individual dark hairs begin to appear.[46] Their eyes open at four to five weeks and their milk teeth erupt about the same time. They emerge from their setts at eight weeks of age, and begin to be weaned at twelve weeks, though they may still suckle until they are four to five months old. Subordinate females assist the mother in guarding, feeding and grooming the cubs.[45] Cubs fully develop their adult coats at six to nine weeks.[46] In areas with medium to high badger populations, dispersal from the natal group is uncommon, though badgers may temporarily visit other colonies.[42] Badgers can live for up to about fifteen years in the wild.[44]

Denning behaviours

Entrance to a badger sett

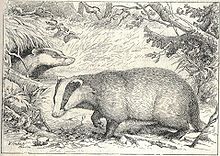

A sett shown in an engraving.

Winter sleep

Badgers begin to prepare for winter sleep during late summer by accumulating fat reserves, which reach a peak in October. During this period, the sett is cleaned and the nesting chamber is filled with bedding. Upon retiring to sleep, badgers block their sett entrances with dry leaves and earth. They typically stop leaving their setts once snow has fallen. In Russia, badgers retire for their winter sleep from late October to mid-November and emerge from their setts in March and early April.[52] In areas such as England and Transcaucasia, where winters are less harsh, badgers either forgo winter sleep entirely or spend long periods underground, emerging in mild spells.[44]Diet

Along with brown bears, European badgers are among the least carnivorous members of the Carnivora;[53] they are highly adaptable and opportunistic omnivores, whose diet encompasses a wide range of animals and plants. Earthworms are their most important food source, followed by large insects, carrion, cereals, fruit and small mammals including rabbits, mice, shrews, moles and hedgehogs. Insect prey includes chafers, dung and ground beetles, caterpillars, leatherjackets, and the nests of wasps and bumblebees. They are able to destroy wasp nests, consuming the occupants, combs, and envelope, such as that of Vespula rufa nests, since thick skin and body hair protect the badgers from stings.[54] Cereal food includes wheat, oats, maize and occasionally barley. Fruits include windfall apples, pears, plums, blackberries, bilberries, raspberries, strawberries, acorns, beechmast, pignuts and wild arum corms.Occasionally, they feed on medium to large birds, amphibians, small reptiles, including tortoises, snails, slugs, fungi, and green food such as clover and grass, particularly in winter and during droughts.[55] Badgers characteristically capture large numbers of one food type in each hunt. Generally, they do not eat more than 0.5 kg (1.1 lb) of food per day, with young specimens yet to attain one year of age eating more than adults. An adult badger weighing 15 kg (33 lb) eats a quantity of food equal to 3.4% of its body weight.[53] Badgers typically eat prey on the spot, and rarely transport it to their setts. Surplus killing has been observed in chicken coops.[42]

A badger in England scavenging food

Relationships with other non-human predators

A red fox challenging two badgers moving towards a bird feeder at night.

Distribution and habitat

The European badger is native to most of Europe and parts of western Asia. In Europe its range includes Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Crete, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Ukraine. In Asia it occurs in Afghanistan, China (Xinjiang), Iran, Iraq and Israel.[1]The distributional boundary between the ranges of European and Asian badgers is the Volga River, the European species being situated on the western bank. They are common in European Russia, with 30,000 individuals having been recorded there in 1990. They are abundant and increasing throughout their range, partly due to a reduction in rabies in Central Europe. In the UK, badgers experienced a 77% increase in numbers during the 1980s and 1990s.[1] The badger population in Great Britain in 2012 is estimated to be 300,000.[60]

The European badger is found in deciduous and mixed woodlands, clearings, spinneys, pastureland and scrub, including Mediterranean maquis shrubland. It has adapted to life in suburban areas and urban parks, although not to the extent of red foxes. In mountainous areas it occurs up to an altitude of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft).[1][44]

Badger tracking to study their behavior and territories has been done in Ireland using Global Positioning Systems.[61]

Status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature rates the European badger as being of least concern. This is because it is a relatively common species with a wide range and populations are generally stable. In Central Europe it has become more abundant in recent decades due to a reduction in the incidence of rabies. In other areas it has also fared well, with increases in numbers in Western Europe and the United Kingdom. However, in some areas of intensive agriculture it has reduced in numbers due to loss of habitat and in others it is hunted as a pest.[1]Diseases and parasites

Bovine tuberculosis (bovine TB) caused by Mycobacterium bovis is a major mortality factor in badgers, though infected badgers can live and successfully breed for years before succumbing. The disease was first observed in badgers in 1951 in Switzerland where they were believed to have contracted it from chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra) or roe deer (Capreolus capreolus).[62] It was detected in the United Kingdom in 1971 where it was linked to an outbreak of bovine TB in cows. The evidence appears to indicate that the badger is the primary reservoir of infection for cattle in the south west of England, Wales and Ireland. Since then there has been considerable controversy as to whether culling badgers will effectively reduce or eliminate bovine TB in cattle.[63]Badgers are vulnerable to the mustelid herpesvirus-1, as well as rabies and canine distemper, though the latter two are absent in Great Britain. Other diseases found in European badgers include arteriosclerosis, pneumonia, pleurisy, nephritis, enteritis, polyarthritis and lymphosarcoma.[64]

Internal parasites of badgers include trematodes, nematodes and several species of tapeworm.[64] Ectoparasites carried by them include the fleas Paraceras melis (the badger flea), Chaetopsylla trichosa and Pulex irritans, the lice Trichodectes melis and the ticks Ixodes ricinus, I. canisuga, I. hexagonus, I. reduvius and I. melicula. They also suffer from mange.[64] They spend much time grooming, individuals concentrating on their own ventral areas, alternating one side with the other, while social grooming occurs with one individual grooming another on its dorsal surface. Fleas tried to avoid the scratching, retreating rapidly downwards and backwards through the fur. This was in contrast to fleas away from their host which ran upwards and jumped when disturbed. The grooming seems to disadvantage fleas rather than merely having a social function.[65]

Relationships with humans

In folklore and literature

Mr. Badger, as portrayed in an illustrated edition of Kenneth Graham's The Wind in the Willows

Tommy Brock, as illustrated by Beatrix Potter in The Tale of Mr. Tod

In Kenneth Graham's The Wind in the Willows, Mr. Badger is depicted as a gruff, solitary figure who "simply hates society", yet is a good friend to Mole and Ratty. As a friend of Toad's now-deceased father, he is often firm and serious with Toad, but at the same time generally patient and well-meaning towards him. He can be seen as a wise hermit, a good leader and gentleman, embodying common sense. He is also brave and a skilled fighter, and helps rid Toad Hall of invaders from the wild wood.[67]

The "Frances" series of children's books by Russell and Lillian Hoban depicts an anthropomorphic badger family.

In T.H. White's Arthurian series The Once and Future King, the young King Arthur is transformed into a badger by Merlin as part of his education. He meets with an older badger who tells him "I can only teach you two things - to dig, and love your home." [68]

A villainous badger named Tommy Brock appears in Beatrix Potter's 1912 book The Tale of Mr. Tod. He is shown kidnapping the children of Benjamin Bunny and his wife Flopsy, and hiding them in an oven at the home of Mr. Tod the fox, whom he fights at the end of the book. The portrayal of the badger as a filthy animal which appropriates fox dens was criticised from a naturalistic viewpoint, though the inconsistencies are few and employed to create individual characters rather than evoke an archetypical fox and badger.[69] A wise old badger named Trufflehunter appears in C. S. Lewis' Prince Caspian, where he aids Caspian X in his struggle against King Miraz.[70]

A badger takes a prominent role in Colin Dann's The Animals of Farthing Wood series as second in command to Fox.[71] The badger is also the house symbol for Hufflepuff in the Harry Potter book series.[72] The Redwall series also has the Badger Lords, who rule the extinct volcano fortress of Salamandastron and are renowned as fierce warriors.[73] The children's television series Bodger & Badger was popular on CBBC during the 1990s and was set around the mishaps of a mashed potato-loving badger and his human companion.[74]

Hunting

Illustration of a badger brought to bay by a Dachshund (Dachshund is German for "badger-dog")

Badger-baiting

Badger-baiting was once a popular blood sport,[77] in which badgers were captured alive, placed in boxes, and attacked with dogs.[78] In the UK, this was outlawed by the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835[78] and again by the Protection of Animals Act of 1911.[79] Moreover, the cruelty towards and death of the badger constitute offences under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992,[80] and further offences under this act are inevitably committed to facilitate badger-baiting (such as interfering with a sett, or the taking or the very possession of a badger for purposes other than nursing an injured animal to health). If convicted, badger-baiters may face a sentence of up to six months in jail, a fine of up to £5,000, and other punitive measures, such as community service or a ban from owning dogs.[81]Culling

Many badgers in Europe were gassed during the 1960s and 1970s to control rabies.[82] Until the 1980s, badger culling in the United Kingdom was undertaken in the form of gassing, to control the spread of bovine tuberculosis (bTB). Limited culling resumed in 1998 as part of a 10-year randomised trial cull which was considered by John Krebs and others to show that culling was ineffective. Some groups called for a selective cull,[83] while others favoured a programme of vaccination, and vets support the cull on compassionate grounds as they say that the illness causes much suffering in badgers.[83] Wales and Northern Ireland are currently (2013) conducting field trials of a badger vaccination programme.[84] In 2012, the government authorised a limited cull[85] led by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), however, this was later deferred with a wide range of reasons given.[86] In August 2013, a full culling programme began where it is expected about 5,000 badgers will be killed over six weeks in West Somerset and Gloucestershire by marksmen with high-velocity rifles using a mixture of controlled shooting and free shooting (some badgers will be trapped in cages first). The cull has caused many protests with emotional, economic and scientific reasons being cited. The badger is considered an iconic species of the British countryside, it has been claimed by shadow ministers that "The government's own figures show it will cost more than it saves...", and Lord Krebs, who led the Randomised Badger Culling Trial in the 1990s, said the two pilots "will not yield any useful information".[84]Domestication

A tame orphan badger with keeper.

Uses

A shaving brush using badger hair.

Some badger products have been used for medical purposes; badger expert Ernest Neal, quoting from an 1810 edition of The Sporting Magazine, wrote;

'The flesh, blood and grease of the badger are very useful for oils, ointments, salves and powders, for shortness of breath, the cough of the lungs, for the stone, sprained sinews, collachs etc. The skin being well dressed is very warm and comfortable for ancient people who are troubled with paralytic disorders.'[88]The hair of the European badger has been used for centuries for making sporrans and high end shaving brushes.[88][77] Sporrans are traditionally worn as part of male Scottish highland dress. They form a bag or pocket made from a pelt and a badger or other animal's mask may be used as a flap.[89] Compared to the fur of other animals, badger's hair is ideal for shaving brushes because it retains the hot water that needs to be applied to the skin while wet shaving.[90] Although some brushes are made from wild badger hair, most hair is sourced from China where badgers are farmed for this purpose.[91] The pelt was also formerly used for pistol furniture.[77]