The osprey tolerates a wide variety of habitats, nesting in any location near a body of water providing an adequate food supply. It is found on all continents except Antarctica, although in South America it occurs only as a non-breeding migrant.

As its other common names suggest, the osprey's diet consists almost exclusively of fish. It possesses specialised physical characteristics and exhibits unique behaviour to assist in hunting and catching prey. As a result of these unique characteristics, it has been given its own taxonomic genus, Pandion and family, Pandionidae. Three subspecies are usually recognized, one of the former subspecies cristatus has recently been given full species status and is referred to as the eastern osprey. Despite its propensity to nest near water, the osprey is not classed as a sea eagle.

Taxonomy and systematics

The osprey was one of the many species described by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae, and named as Falco haliaeetus.[2] The genus, Pandion, is the sole member of the family Pandionidae, and used to contain only one species, the osprey (P. haliaetus). The genus Pandion was described by the French zoologist Marie Jules César Savigny in 1809.[3][4]Most taxonomic authorities consider the species cosmopolitan and conspecific. A few authorities split the osprey into two species, the western osprey and the eastern osprey.

The osprey differs in several respects from other diurnal birds of prey. Its toes are of equal length, its tarsi are reticulate, and its talons are rounded, rather than grooved. The osprey and owls are the only raptors whose outer toe is reversible, allowing them to grasp their prey with two toes in front and two behind. This is particularly helpful when they grab slippery fish.[5] It has always presented something of a riddle to taxonomists, but here it is treated as the sole living member of the family Pandionidae, and the family listed in its traditional place as part of the order Falconiformes.

Other schemes place it alongside the hawks and eagles in the family Accipitridae—which itself can be regarded as making up the bulk of the order Accipitriformes or else be lumped with the Falconidae into Falconiformes. The Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy has placed it together with the other diurnal raptors in a greatly enlarged Ciconiiformes, but this results in an unnatural paraphyletic classification.[6]

Classification

American subspecies

Australasian subspecies is the most distinctive

Californian bird with scraps of fish on its beak

- P. h. haliaetus – (Linnaeus, 1758): Palearctic.[7]

- P. h. carolinensis – (Gmelin, 1788): North America. This form is larger, darker bodied and has a paler breast than nominate haliaetus.[7]

- P. h. ridgwayi – Maynard, 1887: Caribbean islands. This form has a very pale head and breast compared with nominate haliaetus, with only a weak eye mask.[7] It is non-migratory. Its scientific name commemorates American ornithologist Robert Ridgway.[8]

- P. (h.) cristatus – (Vieillot, 1816): coastline and some large rivers of Australia and Tasmania. The smallest and most distinctive subspecies, also non-migratory.[7] (most taxonomists continue to consider this a subspecies. A few authorities have given it full species status[9] as the eastern osprey.[10]

Fossil record

To date there have been two extinct species named from the fossil record.[11] Pandion homalopteron was named by Stuart L. Warter in 1976 from fossils of Middle Miocene, Barstovian age, found in marine deposits in the southern part of California. The second named species Pandion lovensis, was described in 1985 by Jonathan J. Becker from fossils found in Florida and dating to the latest Clarendonian and possibly representing a separate lineage from that of P. homalopteron and P. haliaetus. A number of claw fossils have been recovered from Pliocene and Pleistocene sediments in Florida and South Carolina.The oldest recognized family Pandionidae fossils have been recovered from the Oligocene age Jebel Qatrani Formation, of Faiyum, Egypt. However they are not complete enough to assign to a specific genus.[12] Another Pandionidae claw fossil was recovered from Early Oligocene deposits in the Mainz basin, Germany, and was described in 2006 by Gerald Mayr.[13]

Etymology

The genus name Pandion derives from the mythical Greek king of Athens and grandfather of Theseus, Pandion II. Although Pandion II was not used to name a bird of prey, Nisus, a king of Megara, was used for the genus.[14] The species name haliaetus comes from Ancient Greek haliaietos ἁλιάετος[15] from hali- ἁλι-, "sea-" and aetos άετος, "eagle".[14]The origins of osprey are obscure;[16] the word itself was first recorded around 1460, derived via the Anglo-French ospriet and the Medieval Latin avis prede "bird of prey," from the Latin avis praedæ though the Oxford English Dictionary notes a connection with the Latin ossifraga or "bone breaker" of Pliny the Elder.[17][18] However, this term referred to the Lammergeier.[19]

Description

|

|

Problems playing this file? See media help. |

|

The upperparts are a deep, glossy brown, while the breast is white and sometimes streaked with brown, and the underparts are pure white. The head is white with a dark mask across the eyes, reaching to the sides of the neck.[22] The irises of the eyes are golden to brown, and the transparent nictitating membrane is pale blue. The bill is black, with a blue cere, and the feet are white with black talons.[5] A short tail and long, narrow wings with four long, finger-like feathers, and a shorter fifth, give it a very distinctive appearance.[23]

In flight, over Lake Wylie, South Carolina

The juvenile osprey may be identified by buff fringes to the plumage of the upperparts, a buff tone to the underparts, and streaked feathers on the head. During spring, barring on the underwings and flight feathers is a better indicator of a young bird, due to wear on the upperparts.[22]

In flight, the osprey has arched wings and drooping "hands", giving it a gull-like appearance. The call is a series of sharp whistles, described as cheep, cheep or yewk, yewk. If disturbed by activity near the nest, the call is a frenzied cheereek![24]

Distribution and habitat

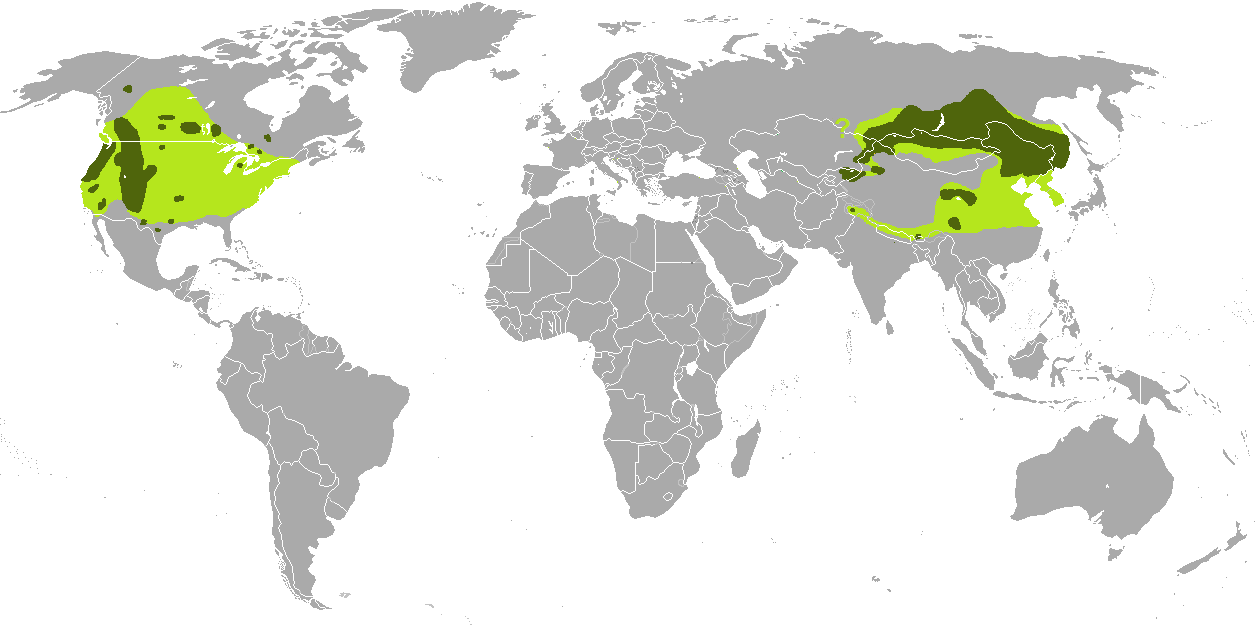

The osprey is the second most widely distributed raptor species, after the peregrine falcon. It has a worldwide distribution and is found in temperate and tropical regions of all continents except Antarctica. In North America it breeds from Alaska and Newfoundland south to the Gulf Coast and Florida, wintering further south from the southern United States through to Argentina.[25] It is found in summer throughout Europe north into Ireland, Scandinavia, Finland and Scotland, England, and Wales though not Iceland, and winters in North Africa.[26] In Australia it is mainly sedentary and found patchily around the coastline, though it is a non-breeding visitor to eastern Victoria and Tasmania.[27]There is a 1,000 km (620 mi) gap, corresponding with the coast of the Nullarbor Plain, between its westernmost breeding site in South Australia and the nearest breeding sites to the west in Western Australia.[28] In the islands of the Pacific it is found in the Bismarck Islands, Solomon Islands and New Caledonia, and fossil remains of adults and juveniles have been found in Tonga, where it probably was wiped out by arriving humans.[29] It is possible it may once have ranged across Vanuatu and Fiji as well. It is an uncommon to fairly common winter visitor to all parts of South Asia,[30] and Southeast Asia from Myanmar through to Indochina and southern China, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines.[31]

Behaviour and ecology

Diet

Eating a fish

Ospreys have vision that is well adapted to detecting underwater objects from the air. Prey is first sighted when the osprey is 10–40 m (33–131 ft) above the water, after which the bird hovers momentarily then plunges feet first into the water.[33]

Occasionally, the osprey may prey on rodents, rabbits, hares, amphibians, other birds,[34] and small reptiles.[35]

Adaptations

The osprey has several adaptations that suit its piscivorous lifestyle :- reversible outer toes[36]

- sharp spicules on the underside of the toes[36]

- closable nostrils to keep out water during dives

- backwards-facing scales on the talons which act as barbs to help hold its catch.

- dense plumage which is oily and prevents its feathers from getting waterlogged.[37]

Reproduction

Preparing to mate on the nest

Osprey standing next to its nest showing their relative sizes

Generally, ospreys reach sexual maturity and begin breeding around the age of three to four, though in some regions with high osprey densities, such as Chesapeake Bay in the U.S., they may not start breeding until five to seven years old, and there may be a shortage of suitable tall structures. If there are no nesting sites available, young ospreys may be forced to delay breeding. To ease this problem, posts are sometimes erected to provide more sites suitable for nest building.[40] In some regions ospreys prefer transmission towers as nesting sites, e.g. in East Germany.[41]

Egg, Collection Museum Wiesbaden

Ospreys usually mate for life. Rarely, polyandry has been recorded.[44] The breeding season varies according to latitude; spring (September–October) in southern Australia, April to July in northern Australia and winter (June–August) in southern Queensland.[38] In spring the pair begins a five-month period of partnership to raise their young. The female lays two to four eggs within a month, and relies on the size of the nest to conserve heat. The eggs are whitish with bold splotches of reddish-brown and are about 6.2 cm × 4.5 cm (2.4 in × 1.8 in) and weigh about 65 g (2.3 oz).[38] The eggs are incubated for about 35–43 days to hatching.[45]

The newly hatched chicks weigh only 50–60 g (1.8–2.1 oz), but fledge in 8–10 weeks. A study on Kangaroo Island, South Australia, had an average time between hatching and fledging of 69 days. The same study found an average of 0.66 young fledged per year per occupied territory, and 0.92 young fledged per year per active nest. Some 22% of surviving young either remained on the island or returned at maturity to join the breeding population.[44] When food is scarce, the first chicks to hatch are most likely to survive. The typical lifespan is 7–10 years, though rarely individuals can grow to as old as 20–25 years.

The oldest European wild osprey on record lived to be over thirty years of age. In North America, great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), and bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) are the only major predators of ospreys, capable of taking both nestlings and adults.[35][46][47][48][49] However, kleptoparasitism by bald eagles, where the larger raptor steals the osprey's catch, is more common than predation. The white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla), which is very similar to the bald eagle, may harass or predate the osprey in Eurasia.[50] Raccoons (Procyon lotor) can be a serious threat to nestlings or eggs if they can access the nest.[51] Endoparasitic trematodes (Scaphanocephalus expansus and Neodiplostomum spp.) have been recorded in wild ospreys.[52]

Migration

European breeders winter in Africa.[53] American and Canadian breeders winter in South America, although some stay in the southernmost U.S. states such as Florida and California.[54] Some ospreys from Florida migrate to South America.[55] Australasian ospreys tend not to migrate.Studies of Swedish ospreys showed that females tend to migrate to Africa earlier than the males. More stopovers are made during their autumn migration. The variation of timing and duration in autumn was more variable than in spring. Although migrating predominantly in the day, they sometimes fly in the dark hours particularly in crossings over water and cover on average 260–280 km (160–170 mi) per day with a maximum of 431 km (268 mi) per day.[56] European birds may also winter in South Asia, an osprey ringed in Norway has been recovered in western India.[57]

Status and conservation

Juvenile on a man-made nest

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the main threats to osprey populations were egg collectors and hunting of the adults along with other birds of prey,[35][58] but osprey populations declined drastically in many areas in the 1950s and 1960s; this appeared to be in part due to the toxic effects of insecticides such as DDT on reproduction.[59] The pesticide interfered with the bird's calcium metabolism which resulted in thin-shelled, easily broken or infertile eggs.[25] Possibly because of the banning of DDT in many countries in the early 1970s, together with reduced persecution, the osprey, as well as other affected bird of prey species, have made significant recoveries.[32] In South Australia, nesting sites on the Eyre Peninsula and Kangaroo Island are vulnerable to unmanaged coastal recreation and encroaching urban development.[28]

Cultural depictions

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder reported that parent ospreys made their young fly up to the sun as a test, and dispatched any that failed.[60]Another odd legend regarding this fish-eating bird of prey, derived from the writings of Albertus Magnus and recorded in Holinshed's Chronicles, was that it had one webbed foot and one taloned foot.[58][61]

There was a medieval belief that fish were so mesmerised by the osprey that they turned belly-up in surrender,[58] and this is referenced by Shakespeare in Act 4 Scene 5 of Coriolanus:

I think he'll be to RomeIn Buddhism, the osprey is sometimes represented as the "King of Birds", especially in 'The Jātaka: Or, Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births' , no. 486.

As is the osprey to the fish, who takes it

By sovereignty of nature.

The osprey is mentioned in the famous Chinese folk poem "guan guan ju jiu" (關關雎鳩); "ju jiu" 雎鳩 refers to the osprey, and "guan guan" (關關) to its voice. In the poem, the osprey is considered to be an icon of fidelity and harmony between wife and husband, due to its highly monogamous habits. Some commentators have claimed that "ju jiu" in the poem is not the osprey but the mallard duck, since the osprey cannot make the sound "guan guan".[62][63]

So-called "osprey" plumes were an important item in the plume trade of the late 19th century and used in hats including those used as part of the army uniform. Despite their name, these plumes were actually obtained from egrets.[64]

The Irish poet William Butler Yeats used a grey wandering osprey as a representation of sorrow in The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems (1889).[60]

In heraldry, the osprey is typically depicted as a white eagle,[61] often maintaining a fish in its talons or beak, and termed a "sea-eagle." It is historically regarded as a symbol of vision and abundance; more recently it has become a symbol of positive responses to nature,[58] and has been featured on more than 50 international postage stamps.[65]

Cap badge of the Selous Scouts was a stylized osprey

In 1994, the osprey was declared the provincial bird of Nova Scotia, Canada.[66] It is also the official bird of Södermanland, Sweden.

The osprey is used as a brand name for various products and sports teams. Examples include: the Ospreys (a Welsh Rugby team); the Richard Stockton College Ospreys (a NCAA Division III intercollegiate athletics team of the U.S. State of New Jersey); the first college in the nation (and the only one for many years) to adopt the osprey as its mascot and athletic team name, North Florida Ospreys (a NCAA Division I intercollegiate athletics team), the Missoula Osprey (a minor league baseball team); the Seattle Seahawks (an American football team of the National Football League); the Wagner Seahawks (a NCAA Division I intercollegiate athletics team); the Cold Spring Harbor Seahawks (a High school football team in Cold Spring Harbor, New York[67]); the Peninsula High School Seahawks (a High School Football Team in Gig Harbor, Washington); and the St. Mary's College of Maryland Seahawks (a NCAA Division III intercollegiate athletics team).

Examples of the osprey used as a mascot include: Ozzie Osprey (of the University of North Florida); Talon the Osprey of New Jersey's Stockton University; Sammy the Seahawk (of University of North Carolina Wilmington); the Wells International Seahawks (of Bangkok, Thailand); the Salve Regina Seahawks (of Newport, Rhode Island); the LA Harbor College Seahawks (of South Bay); and Rowdy the Riverhawk (of the University of Massachusetts Lowell).[68][69]

Binomial name Pandion haliaetus

(Linnaeus, 1758)