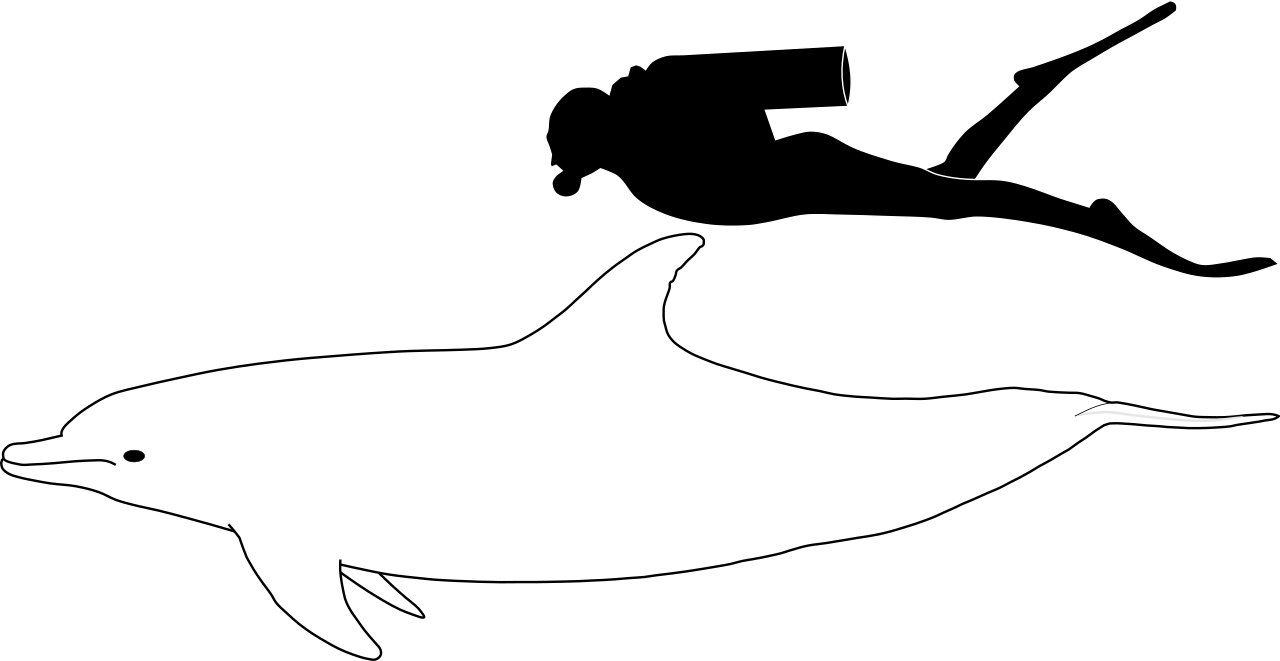

The Amazon river dolphin is the largest species of river dolphin, with adult males reaching 185 kilograms (408 lb) in weight, and 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) in length. Adults acquire a pink color, more prominent in males, giving it its nickname "pink river dolphin". Sexual dimorphism is very evident, with males measuring 16% longer and weighing 55% more than females. Like other toothed whales, they have a melon, an organ that is used for bio sonar. The dorsal fin, although short in height, is regarded as long, and the pectoral fins are also large. The fin size, unfused vertebrae, and its relative size allow for improved manoeuvrability when navigating flooded forests and capturing prey.

They have one of the widest ranging diets among toothed whales, and feed on up to 53 different species of fish, such as croakers, catfish, tetras and piranhas. They also consume other animals such as river turtles and freshwater crabs.[2]

In 2008, this species was ranked by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as being data deficient, due to the uncertainty regarding its population trends and the impact of threats. While hunting is a major threat, in recent decades greater impacts on population have been due to the loss of habitat and inadvertent entanglement in fishing lines.

It is the only species of river dolphin kept in captivity, mainly in the United States, Venezuela and Europe; however, it is difficult to train and a high mortality is seen among captive individuals.

Taxonomy

An Amazon river dolphin as depicted in Brehms Tierleben, 1860's

There is ongoing debate about the classification of species and subspecies with large international bodies being in disagreement. The IUCN recognizes three subspecies:[7]I. g. geoffrensis (Amazon river dolphin), I. g. boliviensis (Bolivian river dolphin) and I. g. humboldtiana (Orinoco river dolphin).[4] While the Committee on Taxonomy of the Society for Marine Mammalogy only recognizes the first two of these.[8]

However, based on skull morphology in 1994, it was proposed that I. g. boliviensis was a different species.[9] In 2002, following the analysis of mitochondrial DNA specimens from the Orinoco basin, the Putumayo River (tributary of the Amazon) and the Tijamuchy and Ipurupuru rivers, geneticists proposed that genus Inia be divided into at least two evolutionary lineages: one restricted to the river basins of Bolivia and the other widely distributed in the Orinoco and Amazon.[10][11] A recent study, with more comprehensive sampling of the Madeira system, including above and below the Teotonio Rapids (which were thought to obstruct gene flow), found that the Inia above the rapids did not possess unique mtDNA.[12] As such the species level distinction once held is not supported by current results. Therefore, the Bolivian river dolphin is currently recognized as a subspecies. In addition, a 2014 study identifies a third species in the Araguaia-Tocantins basin,[13] but this designation is not recognized by any international organization and the Committee on Taxonomy of the Society for Marine Mammalogy suggests this analysis is not persuasive.[8]

Subspecies

The Bolivian river dolphin is a subspecies of Inia geoffrensis

Inia geoffrensis boliviensis[4] has populations in the upper reaches of the Madeira River, upstream of the rapids of Teotonio, in Bolivia. It is confined to the Mamore River and its main tributary, the Iténez.[14]

Inia geoffrensis humboldtiana[4] are located in the Orinoco River basin, including the Apure and Meta rivers. This subspecies is restricted, at least during the dry season, to the waterfalls of Rio Negro rapids in the Orinoco between Samariapo and Puerto Ayacucho, and the Casiquiare canal. This subspecies is not recognized by the Committee on Taxonomy of the Society for Marine Mammalogy,[8] but is recognized by the IUCN.[7]

Biology and ecology

Description

Male Amazon river dolphins are either solid pink or mottled grey/pink.

The texture of the body is robust and strong but flexible. Unlike oceanic dolphins; the cervical vertebrae are not fused, allowing the head to turn 90 degrees.[16] The flukes are broad and triangular, and the dorsal fin, which is keel-shaped, is short in height but very long, extending from the middle of the body to the caudal region. The pectoral fins are large and paddle-shaped. The length of its fins allows the animal to perform a circular movement, allowing for exceptional maneuverability to swim through the flooded forest but decreasing its speed.[17]

The body color varies with age. Newborns and the young have a dark grey tint, which in adolescence transforms into light grey, and in adults turns pink as a result of repeated abrasion of the skin surface. Males tend to be pinker than females due to more frequent trauma from intra-species aggression. The color of adults varies between solid and mottled pink and in some adults the dorsal surface is darker. It is believed that the difference in color depends on the temperature, water transparency, and geographical location. There is one albino on record, kept in an aquarium in Germany.

Amazon river dolphins have a heterodont dentition

Longevity

Apure the dolphin lived for forty years at the Duisburg Zoo

Behavior

The Amazon river dolphin are commonly seen singly or in twos, but may also occur in pods that rarely contain more than eight individuals.[20] Pods as large as 37 individuals have been seen in the Amazon, but average is three. In the Orinoco, the largest observed groups number 30, but average is just above five.[20] Typically, social bonds occur between mother and child, but may also been seen in heterogeneous groups or bachelor groups. The largest congregations are seen in areas with abundant food, and at the mouths of rivers. There is significant segregation during the rainy season, with males occupying the river channels, while females and their offspring are located in flooded areas. However, in the dry season, there is no such separation.[16][21] Due to the high level of prey fish, larger group-sizes are seen in large sections that are directly influenced by whitewater (such as main rivers and lakes, especially during low water season) than in smaller sections influenced by blackwater (such as channels and smaller tributaries).[20] In their freshwater habitat they are apex predators and gatherings depend more on food sources and habitat availability than in oceanic dolphins where protection from larger predators is necessary.[20]Captive studies have shown that the Amazon river dolphin is less shy than the bottlenose dolphin, but also less sociable. It is very curious and has a remarkable lack of fear of foreign objects. However, dolphins in captivity may not show the same behavior that they do in their natural environment, where they have been reported to hold the oars of the fishermen, rub against the boat, pluck underwater plants, and play with sticks, logs, clay, turtles, snakes, and fish.[4]

They are slow swimmers; they commonly travel at speeds of 1.5 to 3.2 kilometres per hour (0.93 to 1.99 mph) but have been recorded to swim at speeds up to 14 to 22 kilometres per hour (8.7 to 13.7 mph). When they surface, the tips of the snout, melon and dorsal fins appear simultaneously, the tail rarely showing before diving. They can also shake their fins, and pull their tail fin and head above the water to observe the environment. They occasionally jump out of the water, sometimes as high as a meter (3.14 ft). They are harder to train than most other species of dolphin.[4]

Courtship

Adult males have been observed carrying objects in their mouths such as branches or other floating vegetation, or balls of hardened clay. The males appear to carry these objects as a socio-sexual display which is part of their mating system. The behavior is "triggered by an unusually large number of adult males and/or adult females in a group, or perhaps it attracts such into the group. A plausible explanation of the results is that object-carrying is aimed at females and is stimulated by the number of females in the group, while aggression is aimed at other adult males and is stimulated by object-carrying in the group."[22] Before determining that the species had an evident sexual dimorphism, it was postulated that the river dolphins were monogamous. Later, it was shown that males were larger than females and are documented wielding an aggressive sexual behavior in the wild and in captivity. Males often have a significant degree of damage in the dorsal, caudal, and pectoral fins, as well as the blowhole, due to bites and abrasions. They also commonly have numerous secondary teeth-raking scars. This suggests fierce competition for access to females, with a polygynous mating system, though polyandry and promiscuity cannot be excluded.[23]In captivity, courtship and mating foreplay have been documented. The male takes the initiative by nibbling the fins of the female, but reacts aggressively if the female is not receptive. A high frequency of copulations in a couple was observed; they used three different positions: contacting the womb at right angles, lying head to head, or head to tail.[6]

Reproduction

Breeding is seasonal, and births occur between May and June. The period of birthing coincides with the flood season, and this may provide an advantage because the females and their offspring remain in flooded areas longer than males. As the water level begins to decrease, the density of food sources in flooded areas increases due to loss of space, providing enough energy for infants to meet the high demands required for growth. Gestation is estimated to be around eleven months and captive births take 4 to 5 hours. At birth, calves are 80 centimetres (31 in) long and in captivity have registered a growth of 0.21 metres (0.69 ft) per year. Lactation takes about a year. The interval between births is estimated between 15 and 36 months, and the young dolphins are thought to become independent within two to three years.[6]The relatively long duration of breastfeeding and parenting suggests a strong mother-child bond. Most couples observed in their natural environment consist of a female and her calf. This suggests that long periods of parental care contribute to learning and development of the young.[6]

Diet

Amazon river dolphin feeding

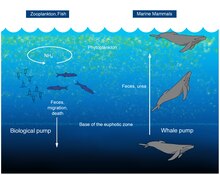

Usually, these dolphins are active and feeding throughout the day and night. However, they are predominantly crepuscular. They consume about 5.5% of their body weight per day. They sometimes take advantage of the disturbances made by boats to catch disoriented prey. Sometimes, they associate with the distantly-related tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis), and giant otters (Pteronura brasiliensis) to hunt in a coordinated manner, by gathering and attacking fish stocks at the same time. Apparently, there is little competition for food between these species, as each prefers different prey. It has also been observed that captive dolphins share food.[2][4]

Echolocation

Amazonian rivers are often very murky, and the Amazon river dolphin is therefore likely to depend much more on its sense of echolocation than vision when navigating and finding prey. However, echolocation in shallow waters and flooded forests may result in many echoes to keep track of. For each click produced a multitude of echoes are likely to return to the echolocating animal almost on top of each other which makes object discrimination difficult. This may be why the Amazon river dolphin produces less powerful clicks compared to other similar sized toothed whales.[24] By sending out clicks of lower amplitude only nearby objects will cast back detectable echoes, and hence fewer echoes need to be sorted out, but the cost is a reduced biosonar range. Toothed whales generally do not produce a new echolocation click until all relevant echoes from the previous click have been received,[25] so if detectable echoes are only reflected back from nearby objects, the echoes will quickly return, and the Amazon river dolphin is then able to click at a high rate.[24] This in turn allow these animals to have a high acoustic update rate on their surroundings which may aid prey tracking when echolocating in shallow rivers and flooded forests with plenty of hiding places for the prey.Communication

Like other dolphins, river dolphins use whistling tones to communicate. The issuance of these sounds is related to the time they return to the surface before diving, suggesting a link to food. Acoustic analysis revealed that the vocalisations are different in structure from the typical whistles of other species of dolphins.[26]Distribution and population

The main branch of the Amazon River near Fonte Boa, Brazil, with multiple floodplains, lakes and smaller channels. The Amazon river dolphin is observed here throughout the year

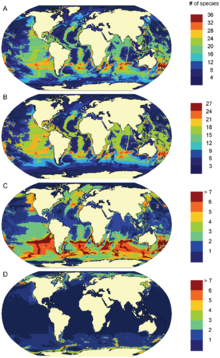

They are also distributed in the basin of the Orinoco River, except the Caroni River and the upper Caura River in Venezuela. The only connection between the Orinoco and the Amazon is through the Casiquiare canal. The distribution of dolphins in the rivers and surrounding areas depends on the time of year; in the dry season they are located in the river beds, but in the rainy season, when the rivers overflow, they disperse to the flooded areas, both the forests and the plains.[4]

Studies to estimate the population are difficult to analyze due to the difference in the methodology used. In a study conducted in the stretch of the Amazon called Solimões River, with a length of 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) between the cities of Manaus and Tabatinga, a total of 332 individuals was sighted ± 55 per inspection. Density was estimated at 0.08- 0.33 animals per square kilometer in the main channels, and 0.49 to 0.93 animals per square kilometer in the branches. In another study, on a stretch of 120 kilometres (75 mi) at the confluence of Colombia, Brazil and Peru, 345 individuals with a density of 4.8 per square km in the tributaries around the islands. 2.7 and 2.0 were observed along the banks. Additionally, another study was conducted in the Amazon at the height of the mouth of the Caqueta River for six days. As a result of the studies conducted, it was found that the density is higher in the riverbanks, 3.7 per km, decreasing towards the center of the river. In studies conducted during the rainy season, the density observed in the flood plain was 18 animals per square km, while on the banks of rivers and lakes ranged from 1.8 to 5.8 individuals per square km. These observations suggest that the Amazon river dolphin is found in higher density than any other cetacean.[4]

Habitat

The Amazon river dolphin is located in most of the area's aquatic habitats, including; river basins, major courses of rivers, canals, river tributaries, lakes, and at the ends of rapids and waterfalls. Cyclical changes in the water levels of rivers take place throughout the year. During the dry season, dolphins occupy the main river channels, and during the rainy season, they can move easily to smaller tributaries, to the forest, and to floodplains.[6]Males and females appear to have selective habitat preferences, with the males returning to the main river channels when water levels are still high, while the females and their offspring remain in the flooded areas as long as possible; probably because it decreases the risk of aggression by males toward the young and predation by other species.[6]

Migration

In the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve, Peru, photo-identification is used to recognize individuals based on pigmentation patterns, scars and abnormalities in the beak. 72 individuals were recognized, of which 25 were again observed between 1991 and 2000. The intervals between sightings ranged from one day to 7.5 years. The maximum range of motion was 220 kilometres (140 mi), with an average of 60.8 kilometres (37.8 mi). The longest distance in one day was 120 kilometres (75 mi), with an average of 14.5 kilometres (9.0 mi).[27] In a previous study conducted at the center of the Amazon River, a dolphin was observed that moved only a few dozen kilometers from the dry season and wet season. However, three of the reviewed 160 animals were observed over 100 kilometres (62 mi) from where they were first registered.[14] Research in 2011 concluded that photo-identification by skilled operatives using high-quality digital equipment could be a useful tool in monitoring population size, movements and social patterns.[28]Interactions with humans

In captivity

A trained Amazon river dolphin at the Acuario de Valencia

Threats

The region of the Amazon in Brazil has an extension of 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi) containing diverse fundamental ecosystems.[29][30] One of these ecosystems is a floodplain, or a várzea forest, and is home to a large number of fish species which are an essential resource for human consumption.[31] The várzea is also a major source of income through excessive local commercialized fishing.[29][32][33] Várzea consists of muddy river waters containing a vast number and diversity of nutrient rich species.[22] The abundance of distinct fish species lures the Amazon River dolphin into the várzea areas of high water occurrences during the seasonal flooding.[34]In addition to attracting predators such as the Amazon river dolphin, these high-water occurrences are an ideal location to draw in the local fisheries. Human fishing activities directly compete with the dolphins for the same fish species, the tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) and the pirapitinga (Piaractus brachypomus), resulting in deliberate or unintentional catches of the Amazon river dolphin.[35][36][37][29][38][39][40][41] The local fishermen overfish and when the Amazon River dolphins remove the commercial catch from the nets and lines, it causes damages to the equipment and the capture, as well as generating ill will from the local fishermen.[37] [39][40] The negative reactions of the local fishermen are also attributed to the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources prohibition on killing the Amazon river dolphin, yet not compensating the fishermen for the damage done to their equipment and catch.[41]

During the process of catching the commercialized fish, the Amazon river dolphins get caught in the nets and exhaust themselves until they die, or the local fishermen deliberately kill the entangled dolphins.[31] The carcasses are discarded, consumed, or used as bait to attract a scavenger catfish, the piracatinga (Calophysus macropterus).[31][42] The use of the Amazon river dolphin carcass as bait for the piracatinga dates back to 2000.[42] Increasing demand for the piracatinga has created a market for distribution of the Amazon river dolphin carcasses to be used as bait throughout these regions.[41]

Of the 15 dolphin carcasses found in the Japurá River in 2010–2011 surveys, 73% of the dolphins were killed for bait, disposed of, or abandoned in entangled gillnets.[31] The data do not fully represent the actual overall number of deaths of the Amazon river dolphins, whether accidental or intentional, because a variety of factors make it extremely complicated to record and medically examine all the carcasses.[31][36][39] Scavenger species feed upon the carcasses, and the complexity of the river currents make it nearly impossible to locate all of the dead animals.[31] More importantly, the local fishermen do not report these deaths out of fear that a legal course of action will be taken against them,[31] as the Amazon river dolphin and other cetaceans are protected under a Brazilian federal law prohibiting any takes, harassments, and kills of the species.[43]

Conservation

In 2008, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) expressed concern for captured botos for use as bait in the Central Amazon, which is an emerging problem that has spread on a large scale. The species is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species Fauna and Flora (CITES), and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals,[44] because it has an unfavorable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organized by tailored agreements.According to a previous assessment by the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission in 2000, the population of botos appears great and there is little or no evidence of population decline in numbers and range. However, increased human intervention on their habitat is expected to, in the future, be the most likely cause of the decline of its range and population. A series of recommendations were issued to ensure proper follow-up to the species, among which is the implementation and publication of studies on the structure of populations, making a record of the distribution of the species, information about potential threats as the magnitude of fishing operations and location of pipelines.[45]

In September 2012, Bolivian President Evo Morales enacted a law to protect the dolphin and declared it a national treasure.[16][46]

In 2008, the species was listed on the Red list of endangered species, but in 2011, the IUCN stated it as Data Deficient (DD).[1] The species was previously listed as "vulnerable" but the conservation status changed due to the limited amount of currently available information on threats, ecology, and population trends. In areas where these dolphins have been studied, they appear well extended and relatively abundant. However, these areas represent only a small proportion of the total distribution of the species and are often sites where the animals are protected. Consequently, the information from these areas may not be representative, and may not be valid in the long term.[1]

Increasing pollution and gradual destruction of the Amazon rainforest add to the vulnerability of the species. The biggest threats are deforestation and other human activities that contribute to disrupt and alter their environment.[4] Another source of concern is the difficulty in keeping these animals alive in captivity, due to intra-species aggression and low longevity. Captive breeding is not considered a conservation option for this species.[47]

In mythology

In traditional Amazon River folklore, at night, an Amazon river dolphin becomes a handsome young man who seduces girls, impregnates them, and then returns to the river in the morning to become a dolphin again. Similarly, the female becomes a beautiful, well - dressed,wealthy - looking and young woman. She goes to the house of a married man, places him under a spell to keep him quiet, and takes him to a thatched hut and visits him every year on the same night she seduced him. On the 7th night of visiting, she changes the man into a female - baby or male, and soon transfers it into his own wife's womb. The mythology is said to be the cycle of a baby. This dolphin shapeshifter is called an encantado. The myth has been suggested to have arisen partly because dolphin genitalia bear a resemblance to those of humans. Others believe the myth served (and still serves) as a way of hiding the incestuous relations which are quite common in some small, isolated communities along the river.[48] In the area, tales relate it is bad luck to kill a dolphin. Legend also states that if a person makes eye contact with an Amazon river dolphin, he or she will have lifelong nightmares. Local legends also state that the dolphin is the guardian of the Amazonian manatee, and that if one should wish to find a manatee, one must first make peace with the dolphin.Associated with these legends is the use of various fetishes, such as dried eyeballs and genitalia.[48] These may or may not be accompanied by the intervention of a shaman. A recent study has shown, despite the claim of the seller and the belief of the buyers, none of these fetishes is derived from the boto. They are derived from Sotalia guianensis, are most likely harvested along the coast and the Amazon River delta, and then are traded up the Amazon River. In inland cities far from the coast, many, if not most, of the fetishes are derived from domestic animals such as sheep and pigs.[49]