Terminology

Male rabbits are called bucks; females are called does. An older term for an adult rabbit is coney, while rabbit once referred only to the young animals.[2] Another term for a young rabbit is bunny, though this term is often applied informally (especially by children) to rabbits generally, especially domestic ones. More recently, the term kit or kitten has been used to refer to a young rabbit. A young hare is called a leveret; this term is sometimes informally applied to a young rabbit as well.A group of rabbits is known as a colony or nest (or, occasionally, a warren, though this more commonly refers to where the rabbits live).[3] A group of baby rabbits produced from a single mating is referred to as a litter,[4] and a group of domestic rabbits living together is sometimes called a herd.[5]

Taxonomy

Rabbits and hares were formerly classified in the order Rodentia (rodent) until 1912, when they were moved into a new order, Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). Below are some of the genera and species of the rabbit.Family Leporidae

- Genus Brachylagus

- Pygmy rabbit, Brachylagus idahoensis

- Genus Bunolagus

- Bushman rabbit, Bunolagus monticularis

- Genus Lepus ← NOTE: This genus is considered a hare, not a rabbit

- Genus Nesolagus

- Sumatran striped rabbit, Nesolagus netscheri

- Annamite striped rabbit, Nesolagus timminsi

- Genus Ochoronidae ← NOTE: This genus is considered a pika, not a rabbit

- Genus Oryctolagus

- European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus

- Genus Pentalagus

- Amami rabbit / Ryūkyū rabbit, Pentalagus furnessi

- Genus Poelagus

- Central African Rabbit, Poelagus marjorita

- Genus Prolagidae ← NOTE: This genus is extinct.

- Genus Romerolagus

- Volcano rabbit, Romerolagus diazi

- Genus Sylvilagus

- Swamp rabbit, Sylvilagus aquaticus

- Desert cottontail, Sylvilagus audubonii

- Brush rabbit, Sylvilagus bachmani

- Forest rabbit, Sylvilagus brasiliensis

- Mexican cottontail, Sylvilagus cunicularis

- Dice's cottontail, Sylvilagus dicei

- Eastern cottontail, Sylvilagus floridanus

- Tres Marias rabbit, Sylvilagus graysoni

- Omilteme cottontail, Sylvilagus insonus

- San Jose brush rabbit, Sylvilagus mansuetus

- Mountain cottontail, Sylvilagus nuttallii

- Marsh rabbit, Sylvilagus palustris

- New England cottontail, Sylvilagus transitionalis

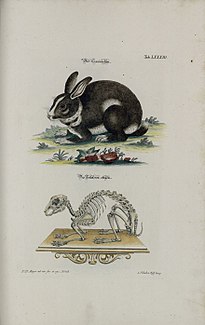

Johann Daniel Meyer (1748)

Johann Daniel Meyer (1748)

Differences from hares

Hares are precocial, born relatively mature and mobile with hair and good vision, while rabbits are altricial, born hairless and blind, and requiring closer care. Hares (and cottontail rabbits) live a relatively solitary life in a simple nest above the ground, while most rabbits live in social groups underground in burrows or warrens. Hares are generally larger than rabbits, with ears that are more elongated, and with hind legs that are larger and longer. Hares have not been domesticated, while descendants of the European rabbit are commonly bred as livestock and kept as pets.Domestication

Rabbits have long been domesticated. Beginning in the Middle Ages, the European rabbit has been widely kept as livestock, starting in ancient Rome. Selective breeding has generated a wide variety of rabbit breeds, many of which (since the early 19th century) are also kept as pets. Some strains of rabbit have been bred specifically as research subjects.As livestock, rabbits are bred for their meat and fur. The earliest breeds were important sources of meat, and so became larger than wild rabbits, but domestic rabbits in modern times range in size from dwarf to giant. Rabbit fur, prized for its softness, can be found in a broad range of coat colors and patterns, as well as lengths. The Angora rabbit breed, for example, was developed for its long, silky fur, which is often hand-spun into yarn. Other domestic rabbit breeds have been developed primarily for the commercial fur trade, including the Rex, which has a short plush coat.

Biology

Evolution

(wax models)

Morphology

Oryctologus cuniculus

European rabbit (wild)

As a result of the position of the eyes in its skull, the rabbit has a field of vision that encompasses nearly 360 degrees, with just a small blind spot at the bridge of the nose.[10]

Hind limb elements

This

image comes from a specimen in the Pacific Lutheran University natural

history collection. It displays all of the skeletal articulations of

rabbit's hind limbs.

Musculature

The rabbits hind limb (lateral view) includes muscles involved in the quadriceps and hamstrings.

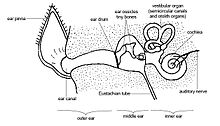

Ears

Within the order lagomorphs, the ears are utilized to detect and avoid predators. In the family leporidae, the ears are typically longer than they are wide. For example, in black tailed jack rabbits, their long ears cover a greater surface area relative to their body size that allow them to detect predators from far away. Contrasted to cotton tailed rabbits, their ears are smaller and shorter, requiring predators to be closer to detect them before fleeing. Evolution has favored rabbits to have shorter ears so the larger surface area does not cause them to lose heat in more temperate regions. The opposite can be seen in rabbits that live in hotter climates, mainly because they possess longer ears that have a larger surface area that help with dispersion of heat as well as the theory that sound does not travel well in more arid air, opposed to cooler air. Therefore, longer ears are meant to aid the organism in detecting prey sooner rather than later in warmer temperatures.[18] The rabbit is characterized by its shorter ears while hares are characterized by their longer ears.[19] Rabbits ears are an important structure to aid thermoregulation and detect predators due to how the outer, middle, and inner ear muscles coordinate with one another. The ear muscles also aid in maintaining balance and movement when fleeing predators.[20]

Anatomy of mammalian ear.

The Auricle (anatomy), also known as the pinna is a rabbit's outer ear.[21] The rabbit's body surface is mainly taken up by the pinnae. It is theorized that the ears aid in dispersion of heat at temperatures above 30°C with rabbits in warmer climates having longer pinnae due to this. Another theory is that the ears function as shock absorbers that could aid and stabilize rabbit's vision when fleeing predators, but this has typically only been seen in hares.[22] The rest of the outer ear has bent canals that lead to the eardrum or tympanic membrane.[23]

Middle ear

The middle ear is filled with three bones called ossicles and is separated by the outer eardrum in the back of the rabbit's skull.The three ossicles are called hammer, anvil, and stirrup and act to decrease sound before it hits the inner ear. In general, the ossicles act as a barrier to the inner ear for sound energy.[23]

Inner ear

Inner ear fluid called endolymph receives the sound energy. After receiving the energy, later within the inner ear there are two parts: the cochlea that utilizes sound waves from the ossicles and the vestibular apparatus that manages the rabbit's position in regards to movement. Within the cochlea there is a basilar membrane that contains sensory hair structures utilized to send nerve signals to the brain so it can recognize different sound frequencies. Within the vestibular apparatus the rabbit possesses three semicircular canals to help detect angular motion.[23]

Thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the process that an organism utilizes to maintain an optimal body temperature even if there are severe external conditions.[24] This process is carried out by the pinnae which takes up most of the rabbit's body surface and contain a vascular network and arteriovenous shunts.[25] In a rabbit, the optimal body temperature is around 21℃.[26] If their body temperature exceeds or does not meet this optimal temperature, the rabbit must return to homeostasis. Homeostasis of body temperature is maintained by the use of their large, highly vascularized ears that are able to change the amount of blood flow that passes through the ears.

Rabbits use their large vascularized ears which aid in thermoregulation to keep their body temperature at an optimal level.

During the summer, the rabbit has the capability to stretch its pinnae which allows for greater surface area and increase heat dissipation. In the winter, the rabbit does the opposite and folds its ears in order to decrease its surface area to the ambient air which would decrease their body temperature.

The jackrabbit has the largest ears within the Oryctolagus cuniculus group. Their ears contribute to 17% of their total body surface area. Their large pinna were evolved to maintain homeostasis while in the extreme temperatures of the desert.

Digestion

Rabbits are herbivores that feed by grazing on grass, forbs, and leafy weeds. In consequence, their diet contains large amounts of cellulose, which is hard to digest. Rabbits solve this problem via a form of hindgut fermentation. They pass two distinct types of feces: hard droppings and soft black viscous pellets, the latter of which are known as caecotrophs and are immediately eaten (a behaviour known as coprophagy). Rabbits reingest their own droppings (rather than chewing the cud as do cows and numerous other herbivores) to digest their food further and extract sufficient nutrients.[27]Rabbits graze heavily and rapidly for roughly the first half-hour of a grazing period (usually in the late afternoon), followed by about half an hour of more selective feeding.[citation needed] In this time, the rabbit will also excrete many hard fecal pellets, being waste pellets that will not be reingested.[citation needed] If the environment is relatively non-threatening, the rabbit will remain outdoors for many hours, grazing at intervals.[citation needed] While out of the burrow, the rabbit will occasionally reingest its soft, partially digested pellets; this is rarely observed, since the pellets are reingested as they are produced.[citation needed]

with ears twitching and a jump

Rabbits are hindgut digesters. This means that most of their digestion takes place in their large intestine and cecum. In rabbits, the cecum is about 10 times bigger than the stomach and it along with the large intestine makes up roughly 40% of the rabbit's digestive tract.[28] The unique musculature of the cecum allows the intestinal tract of the rabbit to separate fibrous material from more digestible material; the fibrous material is passed as feces, while the more nutritious material is encased in a mucous lining as a cecotrope. Cecotropes, sometimes called "night feces", are high in minerals, vitamins and proteins that are necessary to the rabbit's health. Rabbits eat these to meet their nutritional requirements; the mucous coating allows the nutrients to pass through the acidic stomach for digestion in the intestines. This process allows rabbits to extract the necessary nutrients from their food.[29]

The chewed plant material collects in the large cecum, a secondary chamber between the large and small intestine containing large quantities of symbiotic bacteria that help with the digestion of cellulose and also produce certain B vitamins. The pellets are about 56% bacteria by dry weight, largely accounting for the pellets being 24.4% protein on average. The soft feces form here and contain up to five times the vitamins of hard feces. After being excreted, they are eaten whole by the rabbit and redigested in a special part of the stomach. The pellets remain intact for up to six hours in the stomach; the bacteria within continue to digest the plant carbohydrates. This double-digestion process enables rabbits to use nutrients that they may have missed during the first passage through the gut, as well as the nutrients formed by the microbial activity and thus ensures that maximum nutrition is derived from the food they eat.[9] This process serves the same purpose in the rabbit as rumination does in cattle and sheep.[30]

Rabbits are incapable of vomiting.[31] Because rabbits can't vomit, if buildup occurs within the intestines (due often to a diet with insufficient fiber[32]), intestinal blockage can occur.[33]

Sleep

Rabbits may appear to be crepuscular, but their natural inclination is toward nocturnal activity.[34] In 2011, the average sleep time of a rabbit in captivity was calculated at 8.4 hours per day.[35] As with other prey animals, rabbits often sleep with their eyes open, so that sudden movements will awaken the rabbit to respond to potential danger.[36]Diseases

In addition to being at risk of disease from common pathogens such as Bordetella bronchiseptica and Escherichia coli, rabbits can contract the virulent, species-specific viruses RHD ("rabbit hemorrhagic hisease", a form of calicivirus)[37] or myxomatosis. Among the parasites that infect rabbits are tapeworms (such as Taenia serialis), external parasites (including fleas and mites), coccidia species, and Toxoplasma gondii.[38][39] Domesticated rabbits with a diet lacking in high fiber sources, such as hay and grass, are susceptible to potentially lethal gastrointestinal stasis.[40] Rabbits and hares are almost never found to be infected with rabies and have not been known to transmit rabies to humans.[41]Ecology

(one hour after birth)

Habitat and range

Rabbit habitats include meadows, woods, forests, grasslands, deserts and wetlands.[47] Rabbits live in groups, and the best known species, the European rabbit, lives in underground burrows, or rabbit holes. A group of burrows is called a warren.[47]More than half the world's rabbit population resides in North America.[47] They are also native to southwestern Europe, Southeast Asia, Sumatra, some islands of Japan, and in parts of Africa and South America. They are not naturally found in most of Eurasia, where a number of species of hares are present. Rabbits first entered South America relatively recently, as part of the Great American Interchange. Much of the continent has just one species of rabbit, the tapeti, while most of South America's southern cone is without rabbits.

The European rabbit has been introduced to many places around the world.[9]

Environmental problems

Rabbits have been a source of environmental problems when introduced into the wild by humans. As a result of their appetites, and the rate at which they breed, feral rabbit depredation can be problematic for agriculture. Gassing, barriers (fences), shooting, snaring, and ferreting have been used to control rabbit populations, but the most effective measures are diseases such as myxomatosis (myxo or mixi, colloquially) and calicivirus. In Europe, where rabbits are farmed on a large scale, they are protected against myxomatosis and calicivirus with a genetically modified virus. The virus was developed in Spain, and is beneficial to rabbit farmers. If it were to make its way into wild populations in areas such as Australia, it could create a population boom, as those diseases are the most serious threats to rabbit survival. Rabbits in Australia and New Zealand are considered to be such a pest that land owners are legally obliged to control them.[48][49]As food and clothing

[Note rabbit being chased by a (trained?) domesticated hound]

Taddeo Crivelli (Italian, died about 1479)

Simulation of daily life, mid-15th century

Hospices de Beaune, France

Wild leporids comprise a small portion of global rabbit-meat consumption. Domesticated descendants of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) that are bred and kept as livestock (a practice called cuniculture) account for the estimated 200 million tons of rabbit meat produced annually.[51] In 1994, the countries with the highest consumption per capita of rabbit meat were Malta with 8.89 kilograms (19.6 lb), Italy with 5.71 kilograms (12.6 lb), and Cyprus with 4.37 kilograms (9.6 lb), falling to 0.03 kilograms (0.066 lb) in Japan. The figure for the United States was 0.14 kilograms (0.31 lb) per capita. The largest producers of rabbit meat in 1994 were China, Russia, Italy, France, and Spain.[52] Rabbit meat was once a common commodity in Sydney, Australia, but declined after the myxomatosis virus was intentionally introduced to control the exploding population of feral rabbits in the area.

In the United Kingdom, fresh rabbit is sold in butcher shops and markets, and some supermarkets sell frozen rabbit meat. At farmers markets there, including the famous Borough Market in London, rabbit carcasses are sometimes displayed hanging, unbutchered (in the traditional style), next to braces of pheasant or other small game. Rabbit meat is a feature of Moroccan cuisine, where it is cooked in a tajine with "raisins and grilled almonds added a few minutes before serving".[53] In China, rabbit meat is particularly popular in Sichuan cuisine, with its stewed rabbit, spicy diced rabbit, BBQ-style rabbit, and even spicy rabbit heads, which have been compared to spicy duck neck.[51] Rabbit meat is comparatively unpopular elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific.

An extremely rare infection associated with rabbits-as-food is tularemia (also known as rabbit fever), which may be contracted from an infected rabbit.[54] Hunters are at higher risk for tularemia because of the potential for inhaling the bacteria during the skinning process. An even more rare condition is protein poisoning, which was first noted as a consequence of eating rabbit meat to exclusion (hence the colloquial term, "rabbit starvation"). Protein poisoning, which is associated with extreme conditions of the total absence of dietary fat and protein, was noted by Vilhjalmur Stefansson in the late 19th century and in the journals of Charles Darwin.

In addition to their meat, rabbits are used for their wool, fur, and pelts, as well as their nitrogen-rich manure and their high-protein milk.[55] Production industries have developed domesticated rabbit breeds (such as the well-known Angora rabbit) to efficiently fill these needs.

In art, literature, and culture

Rabbits are often used as a symbol of fertility or rebirth, and have long been associated with spring and Easter as the Easter Bunny. The species' role as a prey animal with few defenses evokes vulnerability and innocence, and in folklore and modern children's stories, rabbits often appear as sympathetic characters, able to connect easily with youth of all kinds (for example, the Velveteen Rabbit, or Thumper in Bambi).Marvels of Creatures and

Strange Things Existing

(13th century Iranian book)

Folklore and mythology

The rabbit often appears in folklore as the trickster archetype, as he uses his cunning to outwit his enemies.by showing the reflection of the moon."

Illustration (from 1354) of the Panchatantra

Coat of arms of

Corbenay, France

- In Aztec mythology, a pantheon of four hundred rabbit gods known as Centzon Totochtin, led by Ometotchtli or Two Rabbit, represented fertility, parties, and drunkenness.

- In Central Africa, the common hare (Kalulu), is "inevitably described" as a trickster figure.[56]

- In Chinese folklore, rabbits accompany Chang'e on the Moon. In the Chinese New Year, the zodiacal rabbit is one of the twelve celestial animals in the Chinese zodiac. Note that the Vietnamese zodiac includes a zodiacal cat in place of the rabbit, possibly because rabbits did not inhabit Vietnam.[citation needed] The most common explanation, however, is that the ancient Vietnamese word for "rabbit" (mao) sounds like the Chinese word for "cat" (卯, mao).[57]

- In Japanese tradition, rabbits live on the Moon where they make mochi, the popular snack of mashed sticky rice. This comes from interpreting the pattern of dark patches on the moon as a rabbit standing on tiptoes on the left pounding on an usu, a Japanese mortar.

- In Jewish folklore, rabbits (shfanim שפנים) are associated with cowardice, a usage still current in contemporary Israeli spoken Hebrew (similar to the English colloquial use of "chicken" to denote cowardice).

- In Korean mythology, as in Japanese, rabbits live on the moon making rice cakes ("Tteok" in Korean).

- In Anishinaabe traditional beliefs, held by the Ojibwe and some other Native American peoples, Nanabozho, or Great Rabbit, is an important deity related to the creation of the world.

- A Vietnamese mythological story portrays the rabbit of innocence and youthfulness. The Gods of the myth are shown to be hunting and killing rabbits to show off their power.

- Buddhism, Christianity, and Judaism have associations with an ancient circular motif called the three rabbits (or "three hares"). Its meaning ranges from "peace and tranquility", to purity or the Holy Trinity, to Kabbalistic levels of the soul or to the Jewish diaspora. The tripartite symbol also appears in heraldry and even tattoos.

Anthropomorphized rabbits have appeared in film and literature, in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (the White Rabbit and the March Hare characters), in Watership Down (including the film and television adaptations), in Rabbit Hill (by Robert Lawson), and in the Peter Rabbit stories (by Beatrix Potter). In the 1920s, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, was a popular cartoon character.

"flys with a rabbit's foot talisman,

a gift from a New York girl friend"

Superstition and urban legend

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2018)

|

On the Isle of Portland in Dorset, UK, the rabbit is said to be unlucky and even speaking the creature's name can cause upset among older island residents. This is thought to date back to early times in the local quarrying industry where (to save space) extracted stones that were not fit for sale were set side in what became tall, unstable walls. The local rabbits' tendency to burrow there would weaken the walls and their collapse resulted in injuries or even death. Thus, invoking the name of the culprit became an unlucky act to be avoided. In the local culture to this day, the rabbit (when he has to be referred to) may instead be called a “long ears” or “underground mutton”, so as not to risk bringing a downfall upon oneself. While it was true 50 years ago that a pub on the island could be emptied by calling out the word "rabbit", this has become more fable than fact in modern times.[citation needed]

In other parts of Britain and in North America, invoking the rabbit's name may instead bring good luck. "Rabbit rabbit rabbit" is one variant of an apotropaic or talismanic superstition that involves saying or repeating the word "rabbit" (or "rabbits" or "white rabbits" or some combination thereof) out loud upon waking on the first day of each month, because doing so will ensure good fortune for the duration of that month.

The "rabbit test" is a term, first used in 1949, for the Friedman test, an early diagnostic tool for detecting a pregnancy in humans. It is a common misconception (or perhaps an urban legend) that the test-rabbit would die if the woman was pregnant. This led to the phrase "the rabbit died" becoming a euphemism for a positive pregnancy test.