The Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) is a species of eagle-owl that resides in much of Eurasia. It is also called the European eagle-owl and in Europe, it is occasionally abbreviated to just the eagle-owl.[3] It is one of the largest species of owl, and females can grow to a total length of 75 cm (30 in), with a wingspan of 188 cm (6 ft 2 in), males being slightly smaller.[4]

This bird has distinctive ear tufts, with upper parts that are mottled

with darker blackish colouring and tawny. The wings and tail are barred.

The underparts are a variably hued buff, streaked with darker colour.

The facial disc is not very visible and the orange eyes are distinctive.

The Eurasian eagle-owl is one of the largest living species of owl as well as one of the most widely distributed.[5]

The Eurasian eagle-owl is found in many habitats but is mostly a bird

of mountain regions, coniferous forests, steppes and other relatively

remote places, and have occasionally been found near farmland and in park-like

settings within European cities; in 2020, a brood of three chicks were

raised by their mother on a large, well-foliaged planter on an apartment

window in the city centre of Geel, Belgium.[6][7]

It is a mostly nocturnal predator, hunting for a range of different

prey species, predominantly small mammals but also birds of varying

sizes, reptiles, amphibians, fish, large insects and other assorted

invertebrates. It typically breeds on cliff ledges, in gullies, among

rocks or in other concealed locations. The nest is a scrape in which

averages of two eggs are laid at intervals. These hatch at different

times. The female incubates the eggs and broods the young, and the male

provides food for her and, when they hatch, for the nestlings as well.

Continuing parental care for the young is provided by both adults for

about five months.[8] There are at least 12 subspecies of the Eurasian eagle-owl.[9]

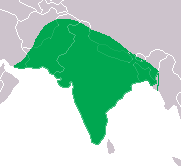

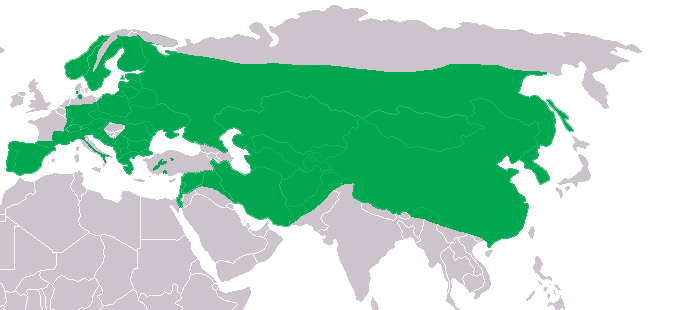

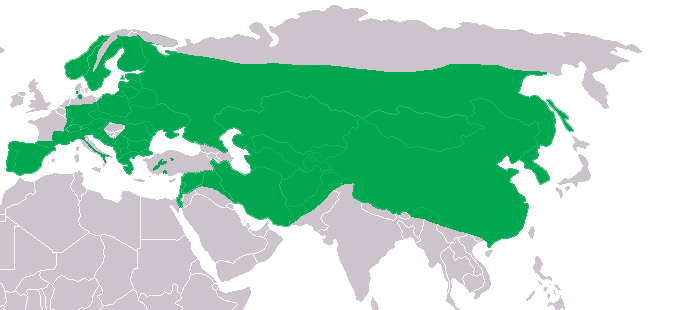

With a total range in Europe and Asia of about 32 million square

kilometres (12 million square miles) and a total population estimated to

be between 250 thousand and 2.5 million, the IUCN lists the bird's conservation status as being of "least concern".[10]

The vast majority of eagle-owls live in mainland Europe, Russia and

Central Asia, and an estimated number of between 12 and 40 pairs are

thought to reside in the United Kingdom as of 2016, a number which may

be on the rise.[11] Tame eagle-owls have occasionally been used in pest control because of their size to deter large birds such as gulls from nesting.[12]

Description

Note the orange eyes and vertical stripes on the chest

The Eurasian eagle-owl is a very large bird, smaller than the

golden eagle (

Aquila chrysaetos) but larger than the

snowy owl (

Bubo scandiacus), despite some overlap in size with both species. It is sometimes referred to as the world's largest owl,

[4][13] although

Blakiston's fish owl (

B. blakistoni) is slightly heavier on average and the much lighter weight

great grey owl (

Strix nebulosa) is slightly longer on average.

[8][14][15]

Heimo Mikkola reported the largest specimens of eagle-owl as having the

same upper body mass, 4.6 kg (10 lb), as the largest Blakiston’s fish

owl and attained a length of around 3 cm (1.2 in) longer.

[4][16]

In terms of average weight and wing size, the Blakiston’s is the

slightly larger species seemingly, even averaging a bit larger in these

aspects than the biggest eagle-owl races from Russia.

[8][15]

Also, although 9 cm (3.5 in) shorter than the largest of the latter

species, the Eurasian eagle-owl can weigh well more than twice as much

as the largest great grey owl.

[4][17] The Eurasian eagle-owl typically has a wingspan of 131–188 cm (4 ft 4 in–6 ft 2 in),

[4] with the largest specimens possibly attaining 200 cm (6 ft 7 in).

[18][19][20] The total length of the species can vary from 56 to 75 cm (22 to 30 in).

[4][8][21] Females can weigh from 1.75 to 4.6 kg (3.9 to 10.1 lb) and males can weigh from 1.22 to 3.2 kg (2.7 to 7.1 lb).

[4] In comparison, the

barn owl (

Tyto alba), the world's most widely distributed owl species, weighs about 500 g (1.1 lb) and the

great horned owl (

Bubo virginianus), which fills the eagle-owl's

ecological niche in North America, weighs around 1.4 kg (3.1 lb).

[22]

Besides the female being larger, there is little external sexual

dimorphism in the Eurasian eagle-owl, although the ear tufts of males

reportedly tend to be more upright than those of females.

[4]

When an eagle-owl is seen on its own in the field, it is generally not

possible to distinguish the individual’s sex. Gender determination by

size is possible via in hand measurements.

[23] Reportedly, in some populations the female may be slightly darker on average than the male.

[5]

The plumage coloration across at least 13 accepted subspecies can be

highly variable. The upper parts may be brown-black to tawny-buff to

pale creamy gray, typically showing dense freckling on the forehead and

crown, stripes on the nape, sides and back of the neck, and dark

splotches on the pale ground colour of the back, mantle and scapulars. A

narrow buff band, freckled with brown or buff, often runs up from the

base of the bill, above the inner part of the eye and along the inner

edge of the black-brown ear tufts. The rump and upper tail-coverts are

delicately patterned with dark vermiculations and fine wavy barring, the

extent of which varies with subspecies. The underwing coverts and

undertail coverts are similar but tend to be more strongly barred in

brownish-black.

[16]

The

primaries and

secondaries are brown with broad dark brown bars and dark brown tips, and grey or buff irregular lines. A complete

moult takes place each year between July and December.

[24]

The facial disc is tawny-buff, speckled with black-brown, so densely on

the outer edge of the disc as to form a "frame" around the face. The

chin and throat are white with a brownish central streak. The feathers

of the upper breast generally have brownish-black centres and

reddish-brown edges except for the central ones which have white edges.

The chin and throat may appear white continuing down the center of the

upper breast. The lower breast and belly feathers are creamy-brown to

tawny buff to off-white with a variable amount of fine dark wavy

barring, on a tawny-buff ground colour. The legs and feet (which are

feathered almost to the talons) are likewise marked on a buff ground

colour but more faintly. The tail is tawny-buff, mottled dark grey-brown

with about six black-brown bars. The bill and feet are black. The iris

is most often orange but is fairly variable. In some European birds, the

iris is a bright reddish, blood-orange colour but then in subspecies

found in arid, desert-like habitats, the iris can range into an

orange-yellow colour (most closely related species generally have

yellowish irises, excluding the

Indian eagle-owl).

[16]

Standard measurements and physiology

The wings have a wide spread

Among standard measurements for the Eurasian eagle-owl, the

wing chord measures 378 to 518 mm (14.9 to 20.4 in), the tail measures 229–310 mm (9.0–12.2 in) long, the

tarsus measures 64.5–112 mm (2.54–4.41 in) and the total length of the

bill is 38.9–59 mm (1.53–2.32 in).

[9][16]

The wings are reportedly the smallest in proportion to the body weight

of any European owl, when measured by the grams per square cm of wing

size, was found to be 0.72. Thus they have quite high

wing loading.

The great horned owl has even smaller wings (0.8 grams per square cm)

relative to its body size. The golden eagle has slightly lower wing

loading proportionately (0.65 grams per square cm), so the aerial

abilities of the two species (beyond the eagle’s spectacular ability to

stoop) may not be as disparate as expected. Some other owls, such as

barn owls,

short-eared owls (

Asio flammeus)

and even the related snowy owls have lower wing loading relative to

their size and so are presumably able to fly faster, with more agility

and for more extended periods than the Eurasian eagle-owl.

[4] In the relatively small race

B. b. hispanus,

the middle claw, the largest talon, (as opposed to rear hallux-claw

which is the largest in accipitrids) was found to measure from 21.6 to

40.1 mm (0.85 to 1.58 in) in length.

[23]

A 3.82 kg (8.4 lb) female examined in Britain (origins unspecified) had

a middle claw measuring 57.9 mm (2.28 in), on par in length with a

large female golden eagle hallux-claw.

[25]

Generally, owls do not have talons as proportionately large as those of

accipitrids but have stronger, more robust feet relative to their size.

Accipitrids use their talons to inflict organ damage and blood loss,

whereas typical owls use their feet to constrict their prey to death,

the talons serving only to hold the prey in place or provide incidental

damage. The talons of the Eurasian eagle-owl are very large and not

often exceeded in size by diurnal raptors. Unlike the great horned owls,

the overall foot size and strength of the Eurasian eagle-owl is not

known to have been tested, but the considerably smaller horned owl has

one of the strongest grips ever measured in a bird.

[8][26]

The feathers of the ear tufts in Spanish birds (when not damaged) were found to measure from 63.3 to 86.6 mm (2.49 to 3.41 in).

[23]

The ear openings (covered in feathers as in all birds) are relatively

uncomplicated but are also large, being larger on the right than on the

left as in most owls, and proportionately larger than those of the great

horned owl. In the female, the ear opening averages 31.7 mm (1.25 in)

on the right and 27.4 mm (1.08 in) on the left and, in males, averages

26.8 mm (1.06 in) on the right and 24.4 mm (0.96 in) on the left.

[8]

The depth of the facial disc and the size and complexity of the ear

opening are directly correlated to the importance of sound in an owl’s

hunting behaviour. Examples of owls with more complicated ear structures

and deeper facial disc are barn owls,

long-eared owls (

Asio otus) and

boreal owls (

Aegolius funereus).

Given the uncomplicated structure of their ear openings and relatively

shallow, undefined facial disc, hunting by ear is secondary to hunting

by sight in the eagle-owl, this seems to be true for

Bubo in

general. It is likely that more sound-based hunters such as the

aforementioned species focus their hunting activity in more complete

darkness. Also owls with white throat patches such as the Eurasian

eagle-owl are more likely to be active in low light conditions in the

hours before and after sunrise and sunset rather than the darkest times

in the middle of the night. The boreal and barn owls, to extend these

examples, lack obvious visual cues such as white throat patches (puffed

up in displaying eagle-owls), again indicative of primary activity being

in darker periods.

[8][27]

Distinguishing from other species

The

great size, bulky, barrel-shaped build, erect ear tufts and orange eyes

render this as a distinctive species. Other than general morphology,

the above features differ markedly from those of two of the next largest

subarctic owl species in Europe and western Asia, which are the great

grey owl and the greyish to chocolate-brown

Ural owl (

Strix uralensis), both of which have no ear tufts and have a distinctly rounded head, rather than the blocky shape of the eagle-owl’s head.

[4][16] The

snowy owl is obviously distinctive from most eagle-owls, but during winter the palest Eurasian eagle-owl race (

B. b. sibiricus)

can appear off-white. Nevertheless, the latter is still distinctively

an ear-tufted Eurasian eagle-owl and lacks the pure white background

colour and variable black spotting of the slightly smaller species

(which has relatively tiny, vestigial ear tufts that have only been

observed to have flared on rare occasions).

[5][16]

The long-eared owl has a somewhat similar plumage to the eagle-owl but

is considerably smaller (an average female eagle-owl may be twice as

long and ten times heavier than an average long-eared owl).

[22]

Unique camouflage pattern

Long-eared owls in

Eurasia

have vertical striping like that of the Eurasian eagle-owl, while

long-eared owls in North America show a more horizontal striping like

that of great horned owls. Whether these are examples of mimicry either

way is unclear but it is known that both

Bubo owls are serious

predators of long-eared owls. The same discrepancy in underside

streaking has also been noted in the Eurasian and American

representations of the grey owl.

[8] A few other related species overlap minimally in range in Asia, mainly in

East Asia and the southern reaches of the Eurasian eagle-owl’s range. Three

fish owls appear to overlap in range, the

brown (

Ketupa zeylonensis) in at least northern

Pakistan, probably

Kashmir and discontinuously in southern Turkey, the

tawny (

K. flavipes) through much of eastern China and Blakiston's fish owl in the

Russian Far East, northeastern China and

Hokkaido.

Fish owls are distinctively different looking, possessing more scraggy

ear tufts that hang to the side rather than sit erect on top of the

head, generally have more uniform, brownish plumages without the

contrasting darker streaking of an eagle-owl. The brown fish owl has no

feathering on the tarsus or feet and the tawny has feathering only on

the upper portion of the tarsi but the Blakiston’s is nearly as

extensively feathered on the tarsi and feet as the eagle-owl. Tawny and

brown fish owls are both slightly smaller than co-occurring Eurasian

eagle-owls and Blakiston’s fish owls are similar or slightly larger than

co-occurring large northern eagle-owls. Fish owls, being tied to the

edges of freshwater where they hunt mainly fish and crabs, also have

slightly differing, and more narrow, habitat preferences.

[4][16]

In the lower

Himalayas

of northern Pakistan and Jammu and Kashmir, along with the brown fish

owl, the Eurasian eagle-owl at the limit of its distribution may

co-exist with at least two to three other eagle-owls.

[8] One of these, the

dusky eagle-owl (

B. coromandus)

is smaller, with more uniform tan-brownish plumage, untidy uniform

light streaking rather than the Eurasian’s dark streaking below and an

even less well-defined facial disc. The dusky is usually found in

slightly more enclosed woodland areas than Eurasian eagle-owls.

[4][16] Another is possibly the

spot-bellied eagle-owl (

Bubo nipalensis),

which is strikingly different looking, with stark brown plumage, rather

than the warm hues typical of the Eurasian, bold spotting on a whitish

background on the belly, and somewhat askew ear tufts that are bold

white with light brown crossbars on the front. It is possible that both

species occur in some parts of the Himalayan foothills but they are not

currently verified to occur in the same area, in part because of the

spot-bellied’s preference for dense, primary forest.

[16]

Most similar, with basically the same habitat preferences and the only

one verified to co-occur with the Eurasian eagle-owls of the race

B. b. turcomanus in Kashmir is the

Indian eagle-owl (

B. bengalensis).

[4]

The Indian species is smaller with a bolder blackish facial disc

border, more rounded and relatively smaller wings and partially

unfeathered toes. Far to the west, the

Pharaoh eagle-owl (

B. ascalaphus) also seemingly overlaps in range with the Eurasian, at least in the country of

Jordan.

Although also relatively similar to the Eurasian eagle-owl, the Pharaoh

eagle-owl is distinguished by its smaller size, paler, more washed-out

plumage and the diminished size of its ear-tufts.

[4][16]

Moulting

The Eurasian eagle-owls’

feathers

are lightweight and robust but nevertheless need to be replaced

periodically as they become worn. In the Eurasian eagle-owl, this

happens in stages and the first moult starts the year after hatching

with some body feathers and wing

coverts being replaced. The next year the three central

secondaries on each wing and three middle tail feathers are shed and regrow, and the following year two or three

primaries

and their coverts are lost. In the final year of this post-juvenile

moult, the remaining primaries are moulted and all the juvenile feathers

will have been replaced. Another moult takes place during years six to

twelve of the bird's life. This happens between June and October after

the conclusion of the breeding season and again it is a staged process

with six to nine main flight feathers being replaced each year. Such a

moulting pattern lasting several years is repeated throughout the bird's

life.

[28]

Taxonomy

The Eurasian eagle-owl is a member of the genus

Bubo, which may include either 22 or 25 extant species. Almost all the larger owl species in the world today are included in

Bubo. Based on an extensive fossil record and a central distribution of extant species on that continent, the

Bubo appears to have evolved into existence in Africa, although early radiations seem to branch from southern Asia as well.

[8] Two genera belonging to the

scops owls complex, the

giant scops owls (

Otus gurneyi) found in Asia and the

Ptilopsis

or the white-faced scops owl found in Africa, although firmly ensconced

in the scops owl group, appear to share some characteristics with the

eagle-owls.

[4][9] The

Strix is also related to the

Bubo and is considered a "sister complex", with the

Pulsatrix possibly being intermediate between the two.

[16] The Eurasian eagle-owl appears to represent an expansion of the genus

Bubo into the Eurasian continent. A few of the other species of

Bubo seem to have been derived from the Eurasian eagle-owl, making it a "

paraspecies", or they at least share a relatively recent common ancestor.

[8] The Pharaoh eagle-owl, distributed in the

Arabian Peninsula and sections of the

Sahara Desert through

North Africa

where rocky outcrops are found, was until recently considered a

subspecies of the Eurasian eagle-owl. It appears that the Pharaoh

eagle-owl differs about 3.8% in

mitochondrial DNA from the Eurasian eagle-owl, well past the minimum genetic difference to differentiate species of 1.5%.

[16]

Smaller and paler than Eurasian eagle-owls, the Pharaoh eagle-owl can

also be considered a distinct species largely due to its higher pitched

and more descending call and the observation that Eurasian eagle-owls

formerly found in

Morocco (

B. b. hispanus) apparently did not breed with the co-existing Pharaoh eagle-owls.

[8][9][16] On the contrary, the race still found together with the Pharaoh eagle-owl in the wild (

B. b. interpositus) in the central

Middle East has been found to interbreed in the wild with the Pharaoh eagle-owl, although genetical materials have indicated

interpositus

may itself be a distinct species from the Eurasian eagle-owl, as it

differs from the nominate subspecies of the Eurasian eagle-owl by 2.8%

in mitochondrial DNA.

[4][16] The Indian eagle-owl (

B. bengalensis)

was also considered a subspecies of the Eurasian eagle-owl until

recently, but its smaller size, distinct voice (more clipped and

high-pitched than the Eurasian), and the fact that it is largely

allopatric in distribution (filling out the

Indian subcontinent) with other Eurasian eagle-owl races has led to it being considered a distinct species.

[29] The mitochondrial DNA of the Indian species also appears considerably distinct from the Eurasian species.

[16] The

Cape eagle-owl (

B. capensis)

appears to represent a return of this genetic line back into the

African continent, where it leads a lifestyle similar to Eurasian

eagle-owls albeit far to the south.

[8] Another offshoot of the northern

Bubo group is the snowy owl. It appears to have separated from other

Bubo at least 4 million years ago.

[16][30]

The fourth and most famous derivation of the evolutionary line that includes the Eurasian eagle-owl is the

great horned owl, which appears to have been the result of primitive eagle-owls spreading into

North America.

[8]

It has been stated that the great horned owls and Eurasian eagle-owls

are barely distinct as species, with a similar level of divergence in

their plumages as the Eurasian and North American representations of the

great grey owl or the long-eared owl.

[8]

There are more outward physical differences between the great horned

owl and the Eurasian eagle-owl than in those two examples, including a

great size difference favoring the Eurasian species, the great horned

owl’s horizontal rather than vertical underside barring, yellow rather

than orange eyes and a much strong black bracket to the facial disc, not

to mention a number of differences in their reproductive behaviour and

distinctive voices.

[16]

Furthermore, genetic research has revealed that the snowy owl is more

closely related to the great horned owl than are Eurasian eagle-owls.

[16]

The most closely related species beyond the Pharaoh, Indian and Cape

eagle-owls to the Eurasian eagle-owl is the smaller, less powerful and

African

spotted eagle-owl (

B. africanus),

which was likely to have divided from the line before they radiated

away from Africa. Somehow, genetic materials indicate the spotted

eagle-owl appears to share a more recent ancestor with the Indian

eagle-owl than with the Eurasian eagle-owl or even the

sympatric Cape eagle-owl.

[16]

Eurasian eagle-owls in captivity have produced apparently healthy

hybrids with both the Indian eagle-owl and the great horned owl.

[4][8]

The pharaoh, Indian and Cape eagle-owls and the great horned owl are

all broadly similar in size to each other, but all are considerably

smaller than the Eurasian eagle-owl, which averages at least 15–30%

larger in linear dimensions and 30–50% larger in body mass than these

other related species, possibly as the eagle-owls adapted to warmer

climates and smaller prey. Fossils from southern France have indicated

that during the

Middle Pleistocene, Eurasian eagle-owls (this paleosubspecies is given the name

B. b. davidi) were larger than they are today, even larger were those found in

Azerbaijan and in the

Caucasus (either

B. b. bignadensis or

B. bignadensis), which were deemed to date to the

Late Pleistocene.

[8] About 12

subspecies are recognized today.

[2]

Subspecies

A captive adult eagle-owl, although identified as part of the subspecies B. b. sibiricus, its appearance is more consistent with B. b. ruthenus.

- B. b. bubo (Linnaeus, 1758) – Also known as the European eagle-owl,[31] the nominate subspecies inhabits continental Europe from near the Arctic Circle in Norway, Sweden, Finland, the southern Kola Peninsula, and Arkhangelsk where it ranges north to about latitude 640 30' N., southward to the Baltic Sea, central Germany, to southeastern Belgium, eastern, central, and southern France to Italy and Sicily, and through Central and Southeastern Europe to Greece. It intergrades with B. b. ruthenus in northern Russia around the basin of the upper Mezen River and in the eastern vicinity of Gorki Leninskiye, Tambov and Voronezh, and intergrades with B. b. interpositus in northern Ukraine.[32][33][34] This is a medium-sized race, measuring in wing chord length 435–480 mm (17.1–18.9 in) in males and 455–500 mm (17.9–19.7 in).[9][34] In captive owls of this subspecies, the mean wingspan were 157 cm (5 ft 2 in) for males and 167.5 cm (5 ft 6 in) for females.[35] The total bill length is 45 to 56 mm (1.8 to 2.2 in).[16]

Adult male European eagle-owls from Norway weigh 1.63 to 2.81 kg (3.6

to 6.2 lb), averaging 2.38 kg (5.2 lb), while females there weigh from

2.28 to 4.2 kg (5.0 to 9.3 lb), averaging 2.95 kg (6.5 lb).[22] Unsurprisingly, adult owls from western Finland were about the same size, averaging 2.65 kg (5.8 lb).[36] The subspecies seems to follow Bergmann’s rule in regards to body size decreasing closer to the Equator, as specimens from central Europe average 2.14 or 2.3 kg (4.7 or 5.1 lb) in body mass and those from Italy average about 2.01 kg (4.4 lb).[37] The weight range for eagle-owls in Italy is 1.5 to 3 kg (3.3 to 6.6 lb).[38]

The nominate subspecies is perhaps the darkest and most richly coloured

of eagle-owl subspecies. Many nominate birds are heavily overlaid with

broad black streaking over the upper-parts, head and chest. While

generally a brownish base-colour, many nominate owls can appear rich

rufous, especially about the head, upper-back and wing primaries. The

lower belly is usually a buff brown, as opposed to whitish or yellowish

in several other subspecies.[32] Birds seen from southern Italy and Sicily

may show a tendency to be smaller than more northern birds and

reportedly are duller, possessing paler ground coloration, and more

narrow streaks, but museum specimens are often not hugely distinct from

north Italian eagle-owls.[32][34] In Scandinavia, some birds are so darkly plumaged as to give a blackish-brown impression with almost no paler colour showing.[5]

- B. b. hispanus (Rothschild and Hartert, 1910) – Also known as the Spanish eagle-owl or the Iberian eagle-owl.[39] This subspecies mainly occurs on the Iberian Peninsula, where it occupies a majority of Spain and scattered spots in Portugal.[32][34] B. b. hispanus at least historically occurred in wooded areas of the Atlas Mountains in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, making it the only subspecies of Eurasian eagle-owl known to breed in Africa, but this population is thought to be extinct.[10][16]

This is a fairly small-bodied subspecies. In males, wing chord length

can range from 400 to 450 mm (16 to 18 in) and in females from 445 to

485 mm (17.5 to 19.1 in). Wingspans in this subspecies can vary from 131

to 168 cm (4 ft 4 in to 5 ft 6 in), averaging about 154.1 cm (5 ft

1 in). Among standard measurements of B. b. hispanus, the tail is 229 to 310 mm (9.0 to 12.2 in), the total bill length is 38.9 to 54.3 mm (1.53 to 2.14 in) and the tarsus is 64.5 to 81 mm (2.54 to 3.19 in). Adult male B. b. hispanus

from Spain weigh 1.22 to 1.9 kg (2.7 to 4.2 lb), averaging 1.63 kg

(3.6 lb), while females weigh from 1.75 to 2.49 kg (3.9 to 5.5 lb),

averaging 2.11 kg (4.7 lb). In terms of its life history, this may be

the most extensively studied subspecies of eagle-owl.[40]

The Spanish eagle-owl is the most similar in plumage to the nominate

subspecies amongst other subspecies, but tends to be a somewhat lighter,

more greyish colour, with generally lighter streaking and a paler

belly.[32]

- B. b. ruthenus (Buturlin and Zhitkov, 1906)- May be also known as the eastern eagle-owl.[41] This subspecies replaces the nominate in eastern Russia from about latitude 660 N. in the Timan-Pechora Basin south to the western Ural Mountains and the upper Don and lower Volga Rivers.[32][33][34]

This is a fairly large subspecies going on wing chord length, which is

430–468 mm (16.9–18.4 in) in males and 470–515 mm (18.5–20.3 in) in

females.[9][34] The subspecies is intermediate in coloration between the nominate subspecies and B. b. sibiricus. B. b. ruthenus may be confused with B. b. interpositus, even by authoritative ornithologists. B. b. interpositus is darker than B. b. ruthenus,

distinctly more yellowish, less gray, and its brown pattern is darker,

heavier, and more regular. The entire colour pattern of B. b. interpositus is brighter, richer, and more contrasting than that of B. b. ruthenus, but B. b. interpositus, though very well characterized, is an intermediate subspecies.[32][33]

- B. b. interpositus (Rothschild and Hartert, 1910)- May be also known as Aharoni’s eagle-owl or the Byzantine eagle-owl.[42][43] B. b. interpositus ranges from southern Russia, south of the nominate, with which it intergrades in northern Ukraine, from Bessarabia and the steppes of the Ukraine north to Kiev and Kharkov then eastward to the Crimea, the Caucasus and Transcaucasia to northwestern and northern Iran (Elburz, region of Tehran, and probably the southern Caspian districts), and through Asia Minor south to Syria and Iraq but not to the Syrian desert where it is replaced by the pharaoh eagle-owl. The latter and B. b. interpositus reportedly hybridize from western Syria south to southern Palestine.[32][34] B. b. interpositus may be a distinct species from the Eurasian eagle-owl based on genetic studies.[9][16] This medium-sized subspecies is about the same size as the nominate subspecies B. b. bubo, with male wing chord lengths 425 to 475 mm (16.7 to 18.7 in) and female lengths of 440 to 503 mm (17.3 to 19.8 in).[9][34]

It differs from the nominate subspecies by being paler and more yellow,

less ferruginous, and by having a sharper brown pattern; from B. b. turcomanus

by being very much darker and less yellow, and also by being much more

sharply and heavily patterned with brown. Aharoni’s eagle-owl is darker

and more rusty than B. b. ruthenus.[32][33]

A captive adult eagle-owl with a pale appearance, likely part of B. b. sibiricus.

- B. b. sibiricus (Gloger, 1833)- Also known as the western Siberian eagle-owl.[44] This subspecies is distributed from the Ural Mountains of western Siberia and Bashkiria to the mid Ob River and the western Altai Mountains, north to limits of the taiga, the most northerly distribution known in the species overall.[32] B. b. sibiricus

is a large subspecies, wherein the males measure 435–480 mm

(17.1–18.9 in) in wing chord length, while the females are 472–515 mm

(18.6–20.3 in).[8][9][34]

Captive males were found to measure 155 to 170 cm (5 ft 1 in to 5 ft

7 in) in wingspan and weigh 1.62 to 3.2 kg (3.6 to 7.1 lb); whereas the

females measure 165 to 190 cm (5 ft 5 in to 6 ft 3 in) in wingspan and

weigh 2.28 to 4.5 kg (5.0 to 9.9 lb).[35] Males were cited with a mean body mass of approximately 2.5 kg (5.5 lb).[45]

This subspecies is physically the most distinctive of all the Eurasian

eagle-owls, and is sometimes considered the most "beautiful and

striking".[32]

It is the most pale of the eagle-owl subspecies; the general coloration

is a buffy off-white overlaid with dark markings. The crown, hindneck

and underparts are streaked blackish but somewhat sparingly, with the

lower breast and belly indistinctly barred, the primary coverts dark,

contrasting with rest of the wing. The head, back and shoulders are only

somewhat dark unlike in most other subspecies. In the eastern limits of

its range, B. b. sibiricus may intergrade with B. b. yenisseensis.[16][32]

- B. b. yenisseensis (Buturlin, 1911)- Also known as the eastern Siberian eagle-owl.[46] This subspecies is found in central Siberia from about the Ob eastward to Lake Baikal, north to about latitudes 580 to 590 N on the Yenisei River, south to the Altai, Tarbagatai and the Saur Mountain ranges and in Tannu Tuva and Khangai Mountains in northwestern Mongolia, grading into B. b. sibiricus near Tomsk in the west and into B. b. ussuriensis

in the east of northern Mongolia. The zone of intergradations with the

latter in Mongolia seems to be quite extensive, with intermediate

eagle-owls being especially prevalent around the Tuul River Valley, resulting in owls intermediate in coloration between B. b. yenisseensis and B. b. ussuriensis.[32][33] B. b. yenisseensis is a large subspecies, with wing chord lengths of 435–470 mm (17.1–18.5 in) in males and 473–518 mm (18.6–20.4 in) in females.[9][34] B. b. yenisseensis is typically much darker with more yellowish ground colour than B. b. sibiricus. It does have a similar amount of dazzling white on its underwing as does sibiricus.[4]

It is buffy-greyish overall with well-expressed dark patterning on the

upper-parts and around the head. The underside is overall pale greyish

with black streaking.[32]

- B. b. jakutensis (Buturlin, 1908)- May be also known as the Yakutian eagle-owl. This subspecies inhabits northeastern Siberia, from southern Yakutia north to about latitude 640 N., west in the basin of the Vilyuy River to the upper Nizhnyaya Tunguska River, and east to the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk from Magadan south to the Khabarovsk Krai. It has been reported farther north, from the regions of the upper Kolyma River and the upper Anadyr. Eurasian eagle-owls are absent in Kamchatka and north of the Verkhoyansk Range.[32]

This is a large subspecies, rivaling the proceeding two subspecies as

the largest of all eagle-owls, going on wing chord length, which

subspecies is largest is unclear considering the extensive size overlap

in wing size. The wing chord is 455 to 490 mm (17.9 to 19.3 in) in males

and 480 to 503 mm (18.9 to 19.8 in) in females.[9][16][34] B. b. jakutensis is much darker and browner above than both B. b. sibiricus and B. b. yenisseensis, though its coloration is more diffused, less sharp than the latter. It is more distinctly streaked and barred below than B. b. sibiricus while being whiter and more heavily vermiculated below than B. b. yenisseensis.[32][33]

- B. b. ussuriensis (Poljakov, 1915) – Would presumably be also known as the Ussuri eagle-owl. This subspecies ranges from southeastern Siberia, to the south of the range of B. b. jakutensis, southward through eastern Transbaikal, Amurland, Sakhalin, Ussuriland and the Manchurian portion of the Chinese provinces of Shaanxi, Shanxi and Hebei.[32][33] This subspecies is also reportedly found in the southern Kuril Islands ranging down to as far as northern Hokkaido,

the only Japanese representation in the Eurasian eagle-owl species,

although this is apparently not a stable, viable population.[47] Going on wing chord length, B. b. ussuriensis

is slightly smaller than the various subspecies from further north in

Siberia. Males have a wing chord length of 430–475 mm (16.9–18.7 in) and

females are 460–502 mm (18.1–19.8 in).[9][32][34] This subspecies differs from B. b. jakutensis by being much darker throughout. It is also darker than B. b. yenisseensis. The brown markings on the upper parts of B. b. ussuriensis are much more extensive and diffused than in B. b. jakutensis or B. b. yenisseensis, with the result that the white markings are much less conspicuous in B. b. ussuriensis

than in the other two subspecies. The under parts are also more buffy,

much less white, and more heavily streaked and vermiculated in B. b. ussuriensis than in the two more northerly, larger subspecies.[32] It overlaps considerably with jakutensis and some birds are of an intermediate appearance.[47]

- B. b. turcomanus (Eversmann, 1835)- Also known as the steppe eagle-owl.[48] It is distributed from Kazakhstan between the Volga and upper Ural Rivers, the Caspian Sea coast and the former Aral Sea, but replaced in that country by B. b. omissus in the mountainous south and in the coastal region of the Mangyshlak Peninsula by B. b. gladkovi. Out of Kazakhstan, the range of B. b. turcomanus continues through the Transbaikal and the Tarim Basin to western Mongolia.[32][33]

This subspecies appears to be variable in size, but is generally

medium-sized. Males can range in wing chord length from 418–468 mm

(16.5–18.4 in) and females from 440 to 512 mm (17.3 to 20.2 in).[9][34]

In standard measurements, the tail is 260–310 mm (10–12 in), the tarsus

is 77–81 mm (3.0–3.2 in) and the bill is 45–47 mm (1.8–1.9 in).[9] This subspecies can reportedly weigh from 1.5 to 3.8 kg (3.3 to 8.4 lb).[49]

The plumage background colour is pale, yellowish-buff. The dark

patterns on the upper- and underparts is paler, less well-defined and

more shattered than in B. b. interpositus. Dark longitudinal patterning on the under-parts discontinue above the belly. B. b. turcomanus is greyer than B. b. hemalachanus

but is otherwise somewhat similar-looking. This subspecies is unique in

that it seems to shun mountainous and obvious rocky habitats in favor

of low hills, plateaus, lowlands, steppes, and semideserts at or near

sea-level.[32]

- B. b. omissus (Dementiev, 1932) – May be also known as the Turkoman eagle-owl or the Turkmenian eagle-owl.[50][51] B. b. omissus is native to Turkmenistan and adjacent regions of northeastern Iran and western Xinjiang.[32][33] This is a small subspecies (only nikolskii

averages smaller among currently accepted races), with males possessing

a wing chord length of 404–450 mm (15.9–17.7 in) and females of 425 to

460 mm (16.7 to 18.1 in).[9][34] B. b. omissus

may be considered a typical sub-desert form. The general coloration is

an ochre to buffy off-yellow; with the dark pattern on the upper- and

under-parts being relatively undefined. The dark shaft-streaks on nape

are very narrow, while the dark longitudinal patterning on the

underparts does not cover the belly. A dark cross-pattern on the belly

and flanks is thinner and paler than in B. b. turcomanus and some individuals may appear almost all pale below. Compared to B. b. nikolskii,

which may occupy the more southern reaches of the same upland ranges,

it is somewhat larger as well as darker, less distinctly yellowish and

more heavily streaked.[32]

- B. b. nikolskii (Zarudny, 1905) – May be also known in English as either the Afghan eagle-owl or the Iranian eagle-owl.[52][53] The range of B. b. nikolskii appears to extend from the Balkan Mountains and Kopet Dagh in southern Transcaspia eastward to southeastern Uzbekistan or to perhaps southwestern Tadzhikistan, then southward 290 N. It may range north to Iran, Afghanistan and Baluchistan south to the region of Kalat, or at about latitude of Hindu Kush. In Iran, B. b. nikolskii is replaced by B. b. interpositus in the north, and probably also in the northwest, and probably by B. b. hemalachana in Badakhshan, part of northeastern Afghanistan. The birds of southern Tadzhikistan found west of the Pamirs are more or less intermediate between B. b. omissus and B. b. hemachalana.[32]

This is the smallest known subspecies of eagle-owl, though the only

known measurements have been of wing chord length. Males can measure 378

to 430 mm (14.9 to 16.9 in) and females can measure 410 to 465 mm (16.1

to 18.3 in) in wing chord.[8][9][34] Other than its smaller size, B. b. nikolskii is distinguished from the somewhat similar B. b. omissus by its rusty wash and being less dark above.[32][33]

- B. b. hemachalana (Hume, 1873) – Also known as the Himalayan eagle-owl.[54] The range of B. b. hemachalana extends from the Himalayas and Tibet, westward to the Tian Shan system in Russian Turkestan, west to the Karatau, north to the Dzungarian Alatau, east to at least the Tekkes Valley in Xinjiang, and south to the regions of Kashgar, Yarkant and probably the western Kunlun Mountains. This bird is partly migratory, descending to the plains of Turkmenistan with colder winter weather, and apparently reaches northern Balochistan.[32]

This is a medium-sized subspecies, though it is larger than other

potentially abutting arid Asian eagle-owl subspecies, which share a

somewhat similar yellowish ground colour. The male attains a wing chord

length of 420–485 mm (16.5–19.1 in), while the female’s wing chord is

450–505 mm (17.7–19.9 in).[9][34] The bill measures 42–45 mm (1.7–1.8 in) in length. 11 adult eagle-owls of the subspecies from the Tibetan Plateau averaged 301 mm (11.9 in) in tail length, 78 mm (3.1 in) in tarsus length and scaled an average of 2.16 kg (4.8 lb) in mass.[55] This subspecies is physically similar to B. b. turcomanus

but the background colour is more light yellowish-brown and less buff.

The dark patterns on the upperparts and underparts are more expressed

and less regular than in B. b. turcomanus and B. b. omissus and the general colour from the mantle to the ear tufts is a more consistent brownish colour than most other abutting races. B. b. hemachalana differs from B. b. yenisseensis

by being much more yellow on the rump, under tail coverts, and outer

tail feathers, rather than grayish or whitish, and the ground coloration

of its body is more yellowish above, and is less whitish below. Dark

longitudinal pattern on the under-parts cover the forebelly.[34]

- B. b. kiautschensis (Reichenow, 1903) – This subspecies could be also known as the North Chinese eagle-owl. It ranges from South Korea and China, south of the range of B. b. ussuriensis, southward to Kwangtung and Yunnan, and inland to Szechwan and southern Kansu.[32]

This is a smallish subspecies, with the male’s wing chord measuring

410–448 mm (16.1–17.6 in) and the female’s being 440–485 mm

(17.3–19.1 in).[9][34] In Korea, this subspecies was found to average 2.26 kg (5.0 lb) in mass, with a range of 1.8 to 2.9 kg (4.0 to 6.4 lb).[56] B. b. kiautschensis is much darker, more tawny and rufous, and slightly smaller than B. b. ussuriensis.

According to museum accounts, it resembles the nominate subspecies from

Europe (though obviously considerably disparate in distribution) rather

closely in coloration but differs from it by being paler, more mottled,

and less heavily marked with brown on the upper parts, by having

narrower dark shaft streaks on the under parts, which average also

duller and more ocher, and by averaging smaller.[32]

Images from South Korea of captive and wild owls show, on the contrary,

that this race may be easily as darkly marked as most nominate

eagle-owls with a more rufous base colour altogether suggesting a richer

and more dusky-colored eagle-owl than from almost any other

population.[57]

- B. b. swinhoei (Hartert, 1913) – This subspecies could be also known as the South Chinese eagle-owl. It is endemic to southeastern China. A quite rufescent form, it is somewhat similar to B. b. kiautschensis.

In this smallish subspecies, the wing chord measures 410–465 mm

(16.1–18.3 in) in both sexes. This is a rather poorly known and

described subspecies and is considered invalid by some authorities.[8][9][32]

Habitat

Eurasian eagle-owls are frequently at home in harsh wintery areas.

Eagle-owls often prefer areas with dense conifers for seclusion.

Eagle-owls are distributed somewhat sparsely but can potentially inhabit a wide range of habitats, with a partiality for

irregular topography.

[58] They have been found in habitats as diverse as northern

coniferous forests to the

edge of vast

deserts.

[16]

Essentially, Eurasian eagle-owls have been found living in almost every

climatic and environmental condition on the Eurasian continent,

excluding the greatest extremities, i.e. they are absent from

humid rainforest in

Southeast Asia, as well as the high

Arctic tundra, both of which they are more or less replaced by other variety of

Bubo owls.

[8] They are often found in the largest numbers in areas where

cliffs and

ravines are surrounded by a scattering of

trees and

bushes.

Grassland areas such as

alpine meadows or

desert-like

steppe can also host them so long as they have the cover and protection of rocky areas.

[59]

The preference of eagle-owls for places with irregular topography has

been reported in most known studies. The obvious benefit of such nesting

locations is that both nests and daytime roosts located in rocky areas

and/or steep slopes would be less accessible to predators, including

man. Also, they may be attracted to the vicinity of

riparian or

wetlands

areas, due to the fact that the soft soil of wet areas is conducive to

burrowing by the small, terrestrial mammals normally preferred in the

diet, such as

voles and

rabbits.

[58]

Due to their preference for rocky areas, the species is often found in

mountainous areas and can be found up to elevations of 2,100 m (6,900 ft) in the

Alps and 4,500 m (14,800 ft) in the

Himalayas and 4,700 m (15,400 ft) in the adjacent

Tibetan Plateau.

[8][55][59] They can also be found living at sea-level and may nest amongst rocky sea cliffs.

[8][16] Despite their success in areas such as

sub-arctic zones

and mountains that are frigid for much of the year, warmer conditions

seem to result in more successful breeding attempts per studies in the

Eifel region of Germany.

[60] In a study from Spain, areas primarily consisting of woodlands (52% of study area being forested) were preferred with

pine trees predominating the

oaks in habitats used, as opposed to truly mixed

pine-oak woodland.

Pine and other coniferous stands are often preferred in great horned

owls as well due to the constant density, which make it more likely to

overlook the large birds.

[8][58] In mountainous forest, they are not generally found in

enclosed wooded areas, as is the

tawny owl (

Strix alucco), instead usually near

forest edge.

[8] Only 2.7% of the habitat included in the territorial ranges for eagle-owls per the habitat study in Spain consisted of

cultivated or

agricultural land.

[58] On the other hand, compared to

golden eagles,

they can visit cultivated land more regularly in hunting forays due to

their nocturnal habits, which allows them to largely evade human

activity.

[8] In the Italian

Alps, it was found that almost no pristine habitat remained and locally eagle-owls nested in the vicinity of

towns,

villages and

ski resorts.

[59]

An eagle-owl at the stadium in Helsinki

Although found in the largest numbers in areas sparsely populated by

humans, farmland is sometimes inhabited and they even have been observed

living in

park-like or other

quiet settings within European cities.

[16] Since 2005, at least five pairs have nested in

Helsinki.

[61] This is due in part to feral

European rabbits (

Oryctolagus cuniculus)

having recently populated the Helsinki area, originally from pet

rabbits released to the wild. The number is expected to increase due to

the growth of the European rabbit population in Helsinki.

European hares (

Lepus europaeus),

the often preferred prey species by biomass of the eagle-owls in their

natural habitat, live only in rural areas of Finland, not in the city

centre. In June 2007, an eagle-owl nicknamed 'Bubi' landed in the

crowded

Helsinki Olympic Stadium

during the European Football Championship qualification match between

Finland and Belgium. The match was interrupted for six minutes.

[62] After tiring of the match, following Jonathan Johansson's opening goal for Finland, the bird left the scene.

[62] Finland's national football team have had the nickname

Huuhkajat (Finnish for "Eurasian eagle-owls") ever since. The owl was named "Helsinki Citizen of the Year" in December 2007.

[63]

Behaviour

The Eurasian eagle-owl is largely nocturnal in activity, as are most

owl species, with its activity focused in the first few hours after

sunset and the last few hours before sunrise.

[64]

In the northern stretches of its range, partial diurnal behaviour has

been recorded, including active hunting in broad daylight during the

late afternoon. In such areas, full nightfall is essentially

non-existent at the peak of summer, so eagle-owls must presumably hunt

and actively brood at the nest during daylight.

[8] The Eurasian eagle-owl has a number of vocalizations that are used at different times.

[16]

It will usually select obvious topographic features such as rocky

pinnacles, stark ridges and mountain peaks to use as regular song posts.

These are dotted along the outer edges of the eagle-owl's territory and

they are visited often but only for a few minutes at a time.

[5]

Vocal activity is almost entirely confined to the colder months

from late fall through winter, with vocal activity in October through

December mainly having territorial purposes and from January to February

being primarily oriented towards courtship and mating purposes.

[65] The territorial song, which can be heard at great distance, is a deep resonant

ooh-hu with emphasis on the first syllable for the male, and a more high-pitched and slightly more drawn-out

uh-hu for the female.

[16]

It is not uncommon for a pair to perform an antiphonal duet. The widely

used name in Germany as well as some other sections of Europe for this

species is

uhu due to its song. At 250–350 Hz, the Eurasian

eagle-owls territorial song or call is deeper, farther-carrying and is

often considering "more impressive" than the territorial songs of the

great horned owl or even that of the slightly larger Blakiston's fish

owl, although the horned owl’s call averages slightly longer in

duration.

[8] Other calls include a rather faint, laughter-like

OO-OO-oo and a harsh

kveck-kveck.

[16] Intruding eagle-owls and other potential dangers may be met with a "terrifying", extremely loud

hooo.

Raucous barks not unlike those of ural owls or long-eared owls have

been recorded but are deeper and more powerful than those species’

barks.

[8]

Annoyance at close quarters is expressed by bill-clicking and cat-like

spitting, and a defensive posture involves lowering the head, ruffling

the back feathers, fanning the tail and spreading the wings.

[24]

Eurasian eagle-owls are subject to frequent mobbing by

crows.

The Eurasian eagle-owl rarely assumes the so-called "tall-thin

position", which is when an owl adopts an upright stance with plumage

closely compressed and may stand tightly beside a tree trunk. Among

others, the

long-eared owl is among the most often reported to sit with this pose.

[24] The great horned owl has been more regularly recorded using the tall-thin, if not as consistently as some

Strix and

Asio owls, and it is commonly thought to aid camouflage if encountering a threatening or novel animal or sound.

[8]

The Eurasian eagle-owl is a broad-winged species and engages in a

strong, direct flight, usually consisting of shallow wing beats and

long, surprisingly fast glides. It has, unusually for an owl, also been

known to soar on updrafts on rare occasions. The latter method of flight

has led them to be mistaken for

Buteos, which are smaller and quite differently proportioned.

[66] Usually when seen flying during the day, it is due to being disturbed by humans or

mobbing crows.

[16] Eurasian eagle-owls are highly

sedentary, normally maintaining a single

territory throughout their adult lives.

Even those near the northern limits of their range, where winters

are harsh and likely to bear little in food, the eagle-owl does not

leave its native range. There are cases from Russia of Eurasian

eagle-owls moving south for the winter, as the

icebound,

infamously harsh climate there is too severe even for these hardy birds

and their prey. Similarly, Eurasian eagle-owls living in the Tibetan

highlands and Himalayas may in some cases vacate their normal

territories when winter hits and move south. Even in those two examples,

there is no evidence of consistent, annual migration by Eurasian

eagle-owls and the birds may eke out a living on their normal

territories even in the sparsest times.

[5][8]

Dietary biology

Breeding

Footage of an adult tending to a nest with juveniles

Eurasian eagle-owls are strictly territorial and will defend their

territories from interloping eagle-owls year around, but territorial

calling appears to peak around October to early January.

[65] Territory size is similar or occasionally slightly greater than great horned owl: averaging 15 to 80 km

2 (5.8 to 30.9 sq mi).

[8]

Territories are established by the male eagle-owl, who selected the

highest points in the territory from which to sing. The high prominence

of singing perches allows their song to be heard at greater distances

and lessens the need for potentially dangerous physical confrontations

in the areas where territories may meet.

[65]

Nearly as important in territorial behaviour as vocalization is the

white throat patch. When taxidermied specimens with flared white throats

were placed around the perimeter of eagle-owl territories, male

eagle-owls reacted quite strongly and often attacked the stuffed owl,

reacting more mildly to a stuffed eagle-owl with a non-flared white

throat. Females were less likely to be aggressive to mounted specimens

and did not seem to vary in their response whether exposed to the

specimens with or without the puffed up white patch.

[67] In January and February, the primary function for vocalization becomes for the purpose of courtship.

[65]

More often than not, eagle-owls will pair for life but usually engage

in courtship rituals annually, most likely to re-affirm pair bonds.

[16]

When calling for the purposes of courtship, males tend to bow and hoot

loudly but do so in a less contorted manner than the male great horned

owl.

[8]

Courtship in the Eurasian eagle-owl may involve bouts of "duetting",

with the male sitting upright and the female bowing as she calls. There

may be mutual bowing, billing and fondling before the female flies to a

perch where

coitus occurs, usually taking place several times over the course of a few minutes.

[24]

The male selects breeding sites and advertises their potential to

the female by flying to them and kneading out a small depression (if

soil is present) and making staccato notes and clucking noises. Several

potential sites may be presented, with the female selecting one.

[16]

Like all owls, Eurasian eagle-owls do not build nests or add material

but nest on the surface or material already present. Eurasian eagle-owls

normally nest on rocks or boulders, most often utilizing cliff ledges

and steep slopes, as well as crevices, gullies, holes or caves. Rocky

areas that also prove concealing woodlots as well as, for hunting

purposes, that border river valleys and grassy scrubland may be

especially attractive.

[8][68] If only low rubble is present, they will nest on the ground between rocks.

[16]

Often, in more densely forested areas, they've been recorded nesting on

the ground, often among roots of trees, under large bushes and under

fallen tree trunks.

[8]

Steep slopes with dense vegetation are preferred if nesting on the

ground, although some ground nests are surprisingly exposed or in flat

spots such as in open spots of the

taiga,

steppe, ledges of river banks and between wide tree trunks.

[16] All Eurasian eagle-owl nests in the largely forested

Altai Krai region of Russia were found to be on the ground, usually at the base of

pines.

[69]

This species does not often use other bird’s nests as does the great

horned owl, which often prefers nests built by other animals over any

other nesting site.

[8] The Eurasian eagle-owl has been recorded in singular cases using nests built by

common buzzards (

Buteo buteo), golden eagle,

greater spotted (

Clanga clanga) and

white-tailed eagles (

Haliaeetus albicilla),

common ravens (

Corvus corax) and

black storks (

Ciconia nigra). Among the eagle-owls of the fairly heavily wooded wildlands of

Belarus, they more commonly utilize nests built by other birds than most eagle-owls, i.e.

stork or

accipitrid nests, but a majority of nests are still located on the ground.

[70]

This is contrary to the indication that ground nests are selected only

if rocky areas or other bird nests are unavailable, as many will utilize

ground nests even where large bird nests seem to be accessible.

[16][70]

Tree holes being used for nesting sites are even more rarely recorded

than nests constructed by other birds. While it may be assumed that the

eagle-owl is too large to utilize tree hollows, when other large species

like the

great grey owl have never been recorded nesting in one, the even more robust

Blakiston's fish owl nests exclusively in cavernous hollows.

[4][8] The Eurasian eagle-owl often uses the same nest site year after year.

[24]

A brooding female on nest

In

Engadin,

Switzerland, the male eagle-owl hunts until the young are 4 to 5 weeks

old and the female spends all her time brooding at the nest. After this

point, the female gradually resumes hunting from both herself and the

young and thus provides a greater range of food for the young.

[8][16] While it may seem contrary to the species’ highly territorial nature, there is one verified cases of

polygamy

in Germany, with a male apparently mating with two females, and

cooperative brooding in Spain, with a third adult of undetermined sex

helping a breeding pair care for the chicks.

[71][72]

The response of Eurasian eagle-owls to humans approaching at the nest

is quite variable. The species is often rather less aggressive than some

other owls, including related species like the spot-bellied eagle-,

great horned and snowy owls, many of the northern

Strix species

and even some rather smaller owl species, which often fearlessly attack

any person found to be nearing their nests. Occasionally, if a person

climbs to an active nest, the adult female eagle-owl will do a

distraction display,

in which they feign an injury. This is an uncommon behaviour in most

owls and most often associated with small birds trying to falsely drawl

the attention of potential predators away from their offspring.

[8]

More commonly, the female flies off and abandons her nest temporarily,

leaving the eggs or small nestlings exposed, when a human approaches it.

[16]

Occasionally, if cornered both adults and nestlings will do an

elaborate threat display, also rare in owls in general, in which the

eagle-owls raise their wings into a semi-circle and puff up their

feathers, followed by a snapping of their bills. Apparently eagle-owls

of uncertain and probably exotic origin in Britain are likely to react

aggressively to humans approaching the nest.

[73]

Also, aggressive encounters involving eagle-owls around their nest,

despite being historically rare, apparently have increased in recent

decades in Scandinavia.

[5] The discrepancy of aggressiveness at the nest between the Eurasian eagle-owl and its

Nearctic counterpart may be correlated to variation in the extent of nest predation that the species endured during the evolutionary process.

[8]

Eggs and offspring development

The eggs are normally laid at intervals of three days and are

incubated only by the female. Laying generally begins in late winter but

may be later in the year in colder habitats. During the incubation

period, the female is brought food at the nest by her mate.

[19]

A single clutch of white eggs is laid; each egg can measure anything

from 56 to 73 mm (2.2 to 2.9 in) long by 44.2 to 53 mm (1.74 to 2.09 in)

in width and will usually weigh about 75 to 80 g (2.6 to 2.8 oz).

[16][19][74] In

Central Europe, eggs average 59.8 mm × 49.5 mm (2.35 in × 1.95 in), and in

Siberia,

eggs average 59.4 mm × 50.1 mm (2.34 in × 1.97 in). Their eggs are only

slightly larger than those of snowy owls and the nominate subspecies of

great horned owl, while similar in size to those of

spot-bellied eagle-owls and Blakiston's fish owls. The Eurasian eagle-owl’s eggs are noticeably larger than those of

Indian and

pharaoh eagle-owls.

[8][16] Usually clutch size is 1 to 2, rarely 3 to 4 and exceptionally to 6.

[8][19] The average number of eggs laid varies with latitude in Europe. Mean clutch size averages 2.02–2.14 in Spain and the

massifs of France, 1.82 to 1.89 in central Europe and the

eastern Alps;

in Sweden and Finland the clutch size averages 1.56 and 1.87,

respectively. While variation based on climate is not unusual for

different wide-ranging

palearctic species, the higher clutch size of western Mediterranean eagle-owls is also probably driven by the presence of

lagomorphs in the diet, which provide high nutritional value than most other regular prey.

[75]

The average clutch size, attributed as 2.7, was the lowest of any

European owl per one study. One species was attributed with an even

lower clutch size in

North America, the great grey owl with a mean of 2.6, but the mean clutch size was much higher for the same species in Europe, at 4.05.

[74]

In Spain, incubation is from mid-January to mid-March, hatching

and early nestling period is from late March to early April, fledging

and post-fledging dependence can be anywhere from mid-April to August

and territorial/courtship is anytime hereafter; i.e. the period between

the beginning of juvenile dispersal to egg laying; from September to

early January.

[64] The same general date parameters were followed in southern France.

[76]

In the Italian Alps, the mean egg-laying date was similarly February 27

but the young were more likely to be dependent later, as all fledglings

were still being cared for by the end of August and some even lingered

under parental care until October.

[59]

The first egg hatches after 31 to 36 days of incubation. The eggs

hatch successively; although the average interval between egg-laying is

three days, the young tend to hatch no more than a day or two apart.

[16]

Like all owls that nest in the open, the downy young are often a

mottled grey with some white and buff, which provides camouflage.

[8] They open their eyes at 4 days of age.

[16] The chicks grow rapidly, being able to consume small prey whole after roughly three weeks.

[24] In

Andalusia,

it was found that the most noticeable development of the young before

they leave the nest was the increase of body size, which was the highest

growth rate of any studied owl and faster than either snowy or great

horned owls.

[77] Body mass increased fourteen times over from 5 days old to 60 days old in this study.

[16][77]

The male continues to bring prey, leaving in on or around the nest, and

the female feeds the nestlings, tearing up the food into suitably-sized

pieces. The female resumes hunting after about three weeks which

increases the food supply to the chicks.

Siblicide has been recorded widely in Eurasian eagle-owls and, according to some authorities, is almost a rule in the species.

[5]

Many nesting attempts produce two fledglings, indicating that siblicide

is not as common as in other birds of prey, especially some

eagles.

[8][78]

It has been theorized in Spain that males are likely to be the first

egg laid to reduce the likelihood of sibling aggression due to the size

difference, thus the younger female hatchling is less likely to be

killed since it is similar in size to its older sibling.

[79]

Apparently, the point at which the chicks venture out of the nest

is driven by the location of the nest. In elevated nest sites, chicks

usually wander out of the nest at 5 to as late as 7 weeks of age, but

have been recorded leaving the nest if the nest is on the ground as

early as 22 to 25 days old.

[16]

The chicks can walk well at five weeks of age and by seven weeks are

taking short flights. Hunting and flying skills are not tested prior to

the young eagle-owls leaving the nest. Young Eurasian eagle-owls leave

the nest by 5–6 weeks of age and typically can be flying weakly (a few

metres) by about 7–8 weeks of age. Normally, they are cared for at least

another month. By the end of the month, the young eagle-owls are quite

assured fliers.

[8]

There are a few confirmed cases of adult eagle-owls in Spain feeding

and caring for post-fledgling juvenile eagle-owls that were not their

own.

[80]

Like

many large owls, Eurasian eagle-owls leave the nest while still in a

functionally flightless state and with large amounts of second down

still present, but will fly shortly thereafter.

A study from southern France found the mean fledgling number of fledgling per nest was 1.67.

[76] In central Europe, the mean number of fledglings per nest averages between 1.8 and 1.9.

[81]

The mean fledgling rate in the Italian Alps was 1.89, thus being

similar. In the Italian Alps it was found that heavier rainfall during

breeding decreased fledgling success because it inhibited the ability of

the parents to hunt and potentially exposed nestlings to hypothermia.

[82] In the reintroduced population of eagle-owls in

Eifel,

Germany, occupied territories produced an average of 1.17 fledglings

but not all occupying pair attempted to breed, with about 23% of those

attempting to breed being unsuccessful.

[60]

In slightly earlier studies, possibly due to higher persecution rates,

the mean number of young leaving the nest was often lower, such as 1.77

in

Bavaria, Germany, 1.1 in

lower Austria and 0.6 in southern Sweden.

[8]

While sibling owls are close in the stage between leaving the nest and

fully fledged, about 20 days after leaving the nest, the family unit

seems to dissolve and the young disperse quickly and directly.

[83]

All told, the dependence of young eagle-owls on their parents last for

20 to 24 weeks. Independence in central Europe is from September to

November. The young leave their parents care normally on their own but

are also sometimes chased away by their parents.

[16]

The young Eurasian eagle-owls reach sexual maturity by the following

year, but do not normally breed until they can establish a territory at

around two or three years old.

[16][19]

Until they are able to establish their own territories, young

eagle-owls spend their life as nomadic "floaters" and, while they also

call, select inconspicuous perch sites unlike breeding birds. Male

floaters are especially wary about intrusion into an established

territory to avoid potential conspecific aggression.

[84]

Status

Europe's highest density of Eurasian eagle-owl is reportedly in the

Svolvær district of

Norway.

The Eurasian eagle-owl has a very wide range across much of Europe

and Asia, estimated to be about 32,000,000 square kilometres

(12,000,000 sq mi). In Europe there are estimated to be between 19,000

and 38,000 breeding pairs and in the whole world around 250,000 to

2,500,000 individual birds. The population trend is thought to be

decreasing because of human activities, but with such a large range and

large total population, the

International Union for Conservation of Nature has rated the bird as being of "

least concern".

[10][85]

Although roughly equal in adaptability and wideness of distribution,

the great horned owl, with a total estimated population of up to 5.3

million individuals, apparently has a total population that is roughly

twice that of the Eurasian eagle-owl. Numerous factors, including a

shorter history of systematic persecution, lesser sensitivity to human

disturbance while nesting, somewhat greater ability to adapt to marginal

habitats and widespread urbanization and slightly smaller territories,

may play into the horned owls greater numbers in modern times.

[4][86]

Longevity

The

eagle-owl can live for up to 20 years in the wild. At one time the

oldest ringed eagle-owl was considered a 19-year-old specimen.

[16] Another banded specimen was subsequently found to be 27 years and 9 months old.

[4]

Like many other bird species in captivity they can live much longer

without having to endure difficult natural conditions, and have possibly

survived up to 68 years in zoo collections.

[4] Healthy adults normally have no natural predators and are thus considered

apex predators.

The leading causes of death for this species are man-made:

electrocution, traffic accidents and shooting frequently claim the life

of eagle-owls.

[16][19]

Anthropogenic mortality

Electrocution

was the greatest cause of mortality in 68% of 25 published studies and

accounted, on average, for 38.2% of the reported eagle-owl deaths. This

was particularly true in the Italian Alps, where the number of

dangerous, non-insulated pylons near nests was extremely high, but is

highly problematic almost throughout the species’ European distribution.

[87][88]

In one telemetry study, 55% of 27 dispersing young were electrocuted

within 1 year of their release from captivity, while electrocution rates

of wild-born young are even higher.

[89][90] Mortality in the Swiss

Rhine Valley

was variable, in radio-tagged, released individuals, most died as a

result of starvation (48%) rather than human-based causes but 93% of the

wild, un-tagged individuals found dead were due to human activities,

46% due to electrocution and 43% due to collision with vehicles or

trains. It was concluded there that insulation of pylons would result in

a stabilisation of the local population due to floaters taking up

residence in non-occupied territories that formerly held deceased

eagle-owls.

[91] Eurasian eagle-owls from Finland were found mainly to die due to electrocution (39%) and collisions with vehicles (22%).

[92] Wind turbine collisions can also be a serious cause of mortality locally.

[93]

Eagle-owl has been singled out historically as a threat to game

species and thus to the economic well-being of landowners, game-keepers

and even governmental agencies and as such has been singled out for

widespread persecution.

[94][95] Local extinctions

of Eurasian eagle-owls have been primarily due to persecution. Examples

of this including northern Germany in 1830, the Netherlands sometimes

in the late nineteenth century, Luxembourg in 1903, Belgium in 1943 and

central and western Germany in the 1960s.

[96]

In trying to determine causes of death for 1476 eagle-owls from Spain,

most were unknown and undetermined types of trauma. The largest group

that could be determined, 411 birds, was due to collisions, more than

half of which were from electrocution, while 313 were due to persecution

and merely 85 were directly attributable to natural causes. Clearly,

while pylon safety is perhaps the most serious factor to be addressed in

Spain, persecution continues to be a massive problem for Spanish

eagle-owls. Of seven European nations where modern Eurasian eagle-owl

mortality is well-studied, continual persecution is by far the largest

problem in Spain, although also continues to be serious (often

comprising at least half of studied mortality) in France. From France

and Spain, nearly equal numbers of eagle-owls are poisoned (for which

raptors might not be the main target), or shot intentionally.

[97][98]

Conservation and re-introductions

Siberian eagle-owl chicks in captivity

While the eagle-owl remains reasonably numerous in some parts of its

habitat where nature is still relatively little disturbed by human

activity, such as the sparsely populated regions of Russia and

Scandinavia, concern has been expressed about the future of the Eurasian eagle-owl in

western

and central Europe. There, very few areas are not heavily modified by

human civilisation, thus exposing the birds to the risk of collisions

with deadly man-made objects (e.g. pylons) and a depletion of native

prey numbers due to ongoing habitat degradation and urbanisation.

[5][8]

In Spain, long-term governmental protection of the Eurasian

eagle-owl seems to have no positive effect on reducing the persecution

of eagle-owls. Therefore, Spanish conservationists have recommended to

boost education and stewardship programs in order to protect eagle-owls

from direct killing by local residents.

[97]

Unanimously, biologists studying eagle-owl mortality and conservation

factors have recommended to proceed with the proper insulation of

electric wires and pylons in areas where the species is present. As this

measure is labour-intensive and therefore rather expensive, few efforts

have actually been made to insulate pylons in areas with few fiscal

resources devoted to conservation such as rural Spain.

[97]

In Sweden, a mitigation project was launched in order to insulate

transformers that are frequently damaged by eagle-owl electrocution.

[99]

Large reintroduction programs were instituted in Germany after the

eagle-owl was deemed extinct in the country as a breeding species by the

1960s, as a result of a long period of heavy persecution.

[100]

The largest reintroduction there occurred from the 1970s to the 1990s

in the Eifel region, near the border with Belgium and Luxembourg. The

success of this measure, consisting in more than a thousand eagle-owls

being reintroduced at an average cost of $1,500 US dollars per bird, is a

subject of controversy. It appears that those eagle-owls reintroduced

in the Eifel region which are able to breed successfully, enjoy a

nesting success comparable with wild eagle-owls from elsewhere in

Europe. On the other hand, mortality levels in the Eifel region appear

to remain quite high due to anthropogenic factors. There are also

concerns about a lack of genetic diversity of the species in this part

of Germany.

[81]

Apparently, the German reintroductions have allowed eagle-owls to

repopulate neighbouring parts of Europe, as the breeding populations now

occurring in the Low Countries (Netherlands, Belgium and

Luxembourg)

are believed to be the result of influx from regions further to the

east. Smaller reintroductions have been done elsewhere and the current

breeding population in Sweden is believed to be primarily the result of a

series of reintroductions.

[73]

Conversely to numerous threats and declines incurred by Eurasian

eagle-owls, areas where human-dependent non-native prey species such as

brown rats (

Rattus norvegicus) and

rock pigeons (

Columba livia)

have flourished, have given the eagle-owls a primary food source and

allowed them occupy regions where they were once marginalized or absent.

[59]

Occurrence in Great Britain

The Eurasian eagle-owl at one time occurred naturally in Great Britain. Some, including the

RSPB, have claimed that it had disappeared about 10,000–9,000 years ago, after the last

ice age, but fossil remains found in

Meare Lake Village indicate the eagle-owl occurring as recently as roughly 2,000 years ago in the fossil record.

[101][102]

The lack of presence of the Eurasian eagle-owl in British folklore or

writings in recent millennium may indicate the lack of occurrence by

this species there.

[73] The