The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum, /ˈhiːlə/ HEE-lə) is a species of venomous lizard native to the southwestern United States and the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora. A heavy, typically slow-moving lizard, up to 60 cm (2.0 ft) long, the Gila monster is the only venomous lizard native to the United States. Its close venomous relatives, the four “Mexican beaded lizards” (former subspecies of Heloderma horridum) inhabit Mexico and Guatemala.[2][3] The Gila monster is venomous, although sluggish in nature and therefore not dangerous to humans. Yet, its fearsome reputation has led to its sometimes being killed, in spite of being protected by state law in Arizona.[1][4]

At the American International Rattlesnake Museum in Albuquerque,History

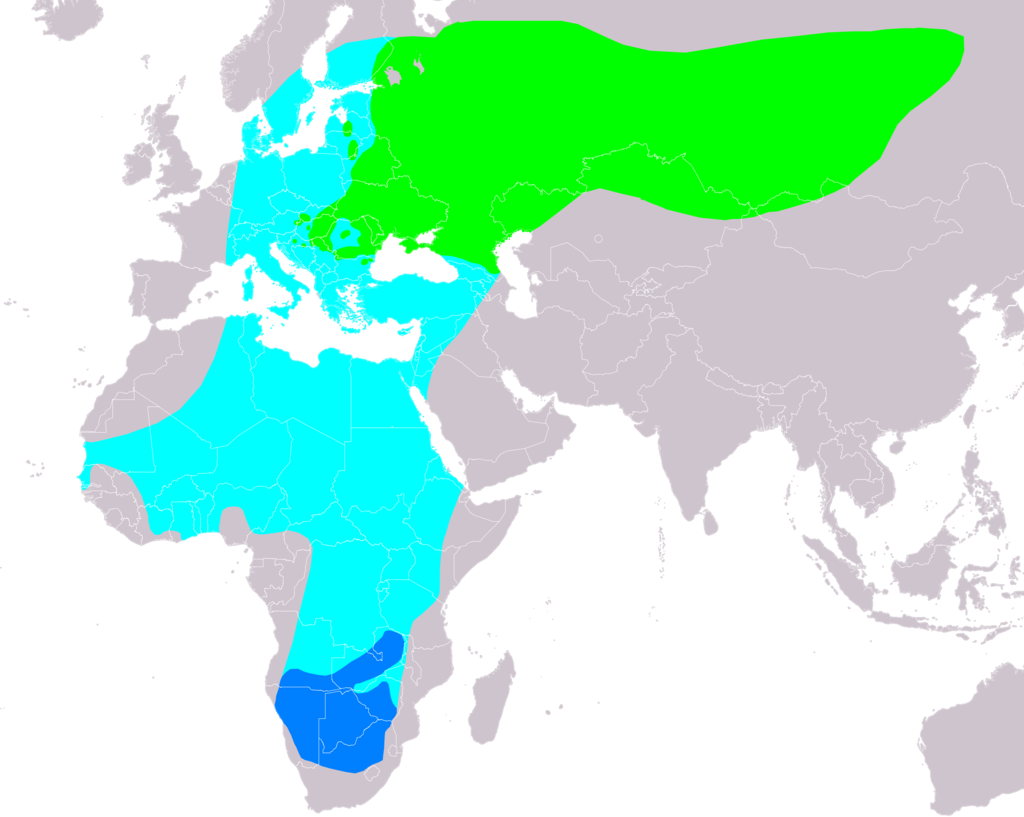

| Explanation of the numbers | |

|---|---|

| 1 | late Eocene (approx. 35 million years) |

| 2 | late Miocene (approx. 10 million years) |

| 3 | Pliocene (approx. 4,4 million years) |

| 4 | Pliocene (approx. 3 million years) |

The name "Gila" refers to the Gila River Basin in the U.S. states of Arizona and New Mexico, where the Gila monster was once plentiful.[6] Heloderma means "studded skin", from the Ancient Greek words helos (ἧλος), "the head of a nail or stud", and derma (δέρμα), "skin". Suspectum comes from the describer, paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. In the beginning (1857) this new specimen of Heloderma was mis-identified and considered to be a northern variation of the Beaded lizard already known from Mexico. He suspected the lizard might be venomous due to the grooves in the teeth.[7]

The Gila monster is the largest extant lizard species native to North America north of the Mexican border. Its snout-to-vent length ranges from 26 to 36 cm (10 to 14 in). The tail is about 20% of the body size and the largest specimens may reach 51 to 56 cm (20 to 22 in) in total length. Body mass is typically in the range of 550 to 800 g (1.21 to 1.76 lb). They appear strong in their body structure with a stout snout, massive head and as “little” appearing eyes, which can be protected by a nictitating membrane.[8][9][2]

The Gila monster has three close living relatives (beaded lizards) in Mexico: Heloderma exasperatum, Heloderma horridum and Heloderma alvaresi as well as another beaded lizard species Heloderma charlesbogerti in Guatemala.[2][3]

The evolutionary history of the Helodermatidae may be traced back to the Cretaceous Period (145 to 166 million years ago), when Gobiderma pulchrum and Estesia mongolensis have been around. The genus Heloderma has existed since the Miocene, when H. texana lived. Fragments of osteoderms from the Gila monster have been found in late Pleistocene (10,000 to 8,000 years ago) deposits near Las Vegas, Nevada. Because the helodermatids have remained relatively unchanged morphologically, they are occasionally regarded as living fossils. Although the Gila monster appears closely related to the monitor lizards (varanids) of Africa, Asia and Australia, their wide geographical separation and unique features not found in the varanids indicate that Heloderma is better placed in a separate family.[10]

Skin

The scales of the head, back and tail contain little pearl shaped bones (osteoderms) similar like in the beaded lizards from further south. The scales of the belly are free from osteoderms. Female Gila monsters go through a total shed about two weeks before depositing their eggs. The dorsal part gets often lost in one large piece. Adult males normally shed in smaller segments in August. Youngsters seem to be in constant shed. Adults have more or less yellow to pink colors on a black surface. Hatchlings have a uniform, “simple” and less colorful pattern. That will drastically change within the first six month of their survival.[11] Hatchlings from the northern area of distribution have a tendency to retain most of their juvenile pattern.

The head of a male is very often more massive and triangular shaped than in females. The length of the tail of the two sexes is statistically very similar and so does not give any hint to the sexes.[12] Individuals with stout tail ends occur in nature and under human breeding.

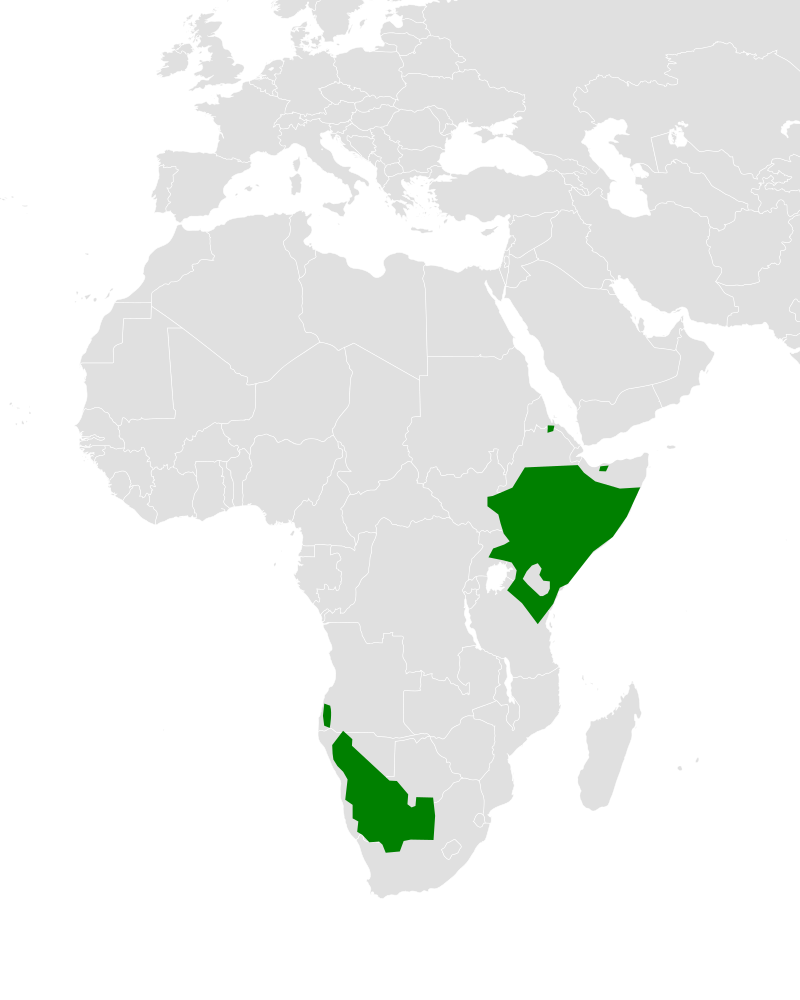

Distribution and habitat

The Gila monster is found in the Southwestern United States and Mexico, a range including Sonora, Arizona, parts of California, Nevada, Utah, and New Mexico. There are no records from Baja California.[2] They inhabit scrubland, succulent desert, and oak woodland, seeking shelter in burrows, thickets, and under rocks in locations with a favorable microclimate and adequate humidity. Gila monsters depend on water resources and might be observed in puddles of water after a summer rain. They avoid living in open areas such as flats and open grasslands.[2]

Ecology

Gila monsters spend 90% of their lifetime underground in burrows or rocky shelters.[2] They are active in the morning during the dry season (spring and early summer). The lizards move to different shelters every four to five days up to the beginning of the summer season. By doing so, they always try to optimize for a suitable microhabitat for survival.[2][13][14] Later in the summer, they may be active on warm nights or after a thunderstorm. They maintain a surface body temperature of about 30 °C (86 °F).[2] Close to 37° C, they are able to decrease their body temperature up to 2° C by an activated, limited evaporation via the cloaca.[15] Gila monsters are slow in sprinting ability, but they have relatively high endurance and maximal aerobic capacity (VO2 max) for a lizard.[16] They are preyed upon by coyotes, badgers and raptors. Hatchlings are preyed on by snakes, e.g. King snakes (Lampropeltis spec.).

Diet

The Gila monster's diet consists of a variety of food items: small mammals (such as young rabbits, mice, ground squirrels, other rodents, etc.), small birds, lizards, and eggs of birds, lizards, snakes, and tortoises.[17][18] It is claimed, that three to four extensive meals in spring give them enough energy for a whole season. Nevertheless, it will feed whenever it comes across suitable prey. Hatchlings will digest their yolk reserve in winter underground for their energy supply and survival.[13] Youngsters can swallow up to 50 % of their body weight at a single meal.[15] Adults may eat up to one-third of their body mass in one meal.[8] Heloderma uses its extremely acute sense of smell to locate prey. The strong, two ended tipped tongue is pigmented in black-blue colors,[11] serves orientation and picks up scent molecules as “chemical information” to be transferred to the opening of the Jacobson organ (vomeronasal organ) at about in the middle of the upper mouth cavern; information is then immediately transported to the brain to be decoded.

Prey may be crushed to death if large or eaten alive, most of the time head first, and helped down by muscular contractions and neck flexing. After food has been swallowed, the Gila monster immediately might resume tongue flicking and search behavior for identifying more prey such as eggs or young in nests. Gila monsters are able to climb trees and cacti and even up fairly straight, rough surfaced walls.[2][19]

Venom

–Dr. Ward, Arizona Graphic, September 23, 1899

Pioneer beliefs

In the Old West, the pioneers believed a number of myths about the Gila monster, including that the lizard had foul or toxic breath and that its bite was fatal.[20] The Tombstone Epitaph of Tombstone, Arizona, wrote about a Gila monster that a local person caught on May 14, 1881:

This is a monster, and no baby at that, it being probably the largest specimen ever captured in Arizona. It is 27 inches long and weighs 35 lb. It was caught by H. C. Hiatt on the road between Tombstone and Grand Central Mill and was purchased by Messrs. Ed Baker and Charles Eastman, who now have it on exhibition at Kelley's Wine House, next door above Grand Hotel, Allen Street. Eastern people who have never seen one of these monsters should not fail to inspect his Aztecship, for they might accidentally stumble upon one some fine day and get badly frightened, except they know what it is.

On May 8, 1890, southeast of Tucson, Arizona Territory, Empire Ranch owner Walter Vail captured and thought he had killed a Gila monster. He tied it to his saddle and it bit the middle finger of his right hand and wouldn't let go. A ranch hand pried open the lizard's mouth with a pocketknife, cut open his finger to stimulate bleeding, and then tied saddle strings around his finger and wrist. They summoned Dr. John C. Handy of Tucson, who took Vail back to Tucson for treatment, but Vail experienced swollen and bleeding glands in his throat for sometime afterward.[20]

Dr. Handy's friend, Dr. George Goodfellow of Tombstone, was among the first to research the actual effects of Gila monster venom. Scientific American reported in 1890 that "The breath is very fetid, and its odor can be detected at some little distance from the lizard. It is supposed that this is one way in which the monster catches the insects and small animals which form a part of its food supply—the foul gas overcoming them." Goodfellow offered to pay local residents $5.00 for Gila monster specimens. He bought several and collected more on his own. In 1891 he purposely provoked one of his captive lizards into biting him on his finger. The bite made him ill and he spent the next five days in bed, but he completely recovered. When Scientific American ran another ill-founded report on the lizard's ability to kill people, he wrote in reply and described his own studies and personal experience. He wrote that he knew several people who had been bitten by Gila monsters but had not died from the bite.[20]

Venom delivery

The Gila monster produces venom in modified salivary glands at the end of its lower jaws, unlike snakes, whose venom is produced in glands behind the eyes.[21] The Gila monster lacks the strong musculature in glands above the eyes; instead in Heloderma, the venom is propelled from the gland via a tubing to the base of the lower teeth and then by capillary forces into two grooves of the tooth and then chewed into the victim.[2] The teeth are tightly anchored to the jar (pleurodont). Broken and regular replacement teeth have to wait every time to go into position in a determinate “wavelike” sequence. They change teeth all their life long.[22][23] The Gila monster's bright colors might be suitable to teach predators not to bother this “painful” creature. Because the Gila monster's prey consists mainly of eggs, small animals, and otherwise "helpless" prey, the Gila monster's venom is thought to have evolved for defensive rather than for hunting use.[24]

Toxicity

The venom of a Gila monster is considered to be as toxic as that of a Western diamondback rattlesnake. Milking H. suspectum for its venom it can yield up to 2 ml. The Gila monster's bite is normally not fatal to healthy adult humans.[20] No reports of fatalities have been confirmed after 1930, and the rare fatalities recorded before that time occurred in adults who were intoxicated by alcohol or by mismanagement in the treatment of the bite.[25] The Gila monster can bite quickly e. g. by swinging its head unexpectedly sideways and hold on tenaciously and painfully. If bitten, the victim may need to fully submerge the attacking lizard in water to hopefully break free from its bite or physically yank the lizard free, risking severe lacerations in the process from the lizard's sharp teeth, but much less of venom delivery. Symptoms of the bite include excruciating pain, edema, and weakness associated with a rapid drop in blood pressure.

One zoological journalist, Coyote Peterson, when giving a report about the pain of a bite, described it as "the worst pain [he] had ever experienced ... it's like hot lava coursing through your veins." It is generally regarded as the most painful venom produced by any vertebrate.[26]

More than a dozen peptides and other substances have been isolated from the Gila monster's venom, including hyaluronidase, serotonin, phospholipase A2, and several kallikrein-like glycoproteins responsible for the pain and edema caused by a bite, without producing a compartment syndrome. Four potentially lethal toxins have been isolated from the Gila monster's venom, which cause hemorrhage in internal organs and exophthalmos (bulging of the eyes),[27] and helothermine, which causes lethargy, partial paralysis of the limbs, and hypothermia in rats. Some are similar in action of the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), which relaxes smooth muscle and regulates water and electrolyte secretion between the small and large intestines. These bioactive peptides are able to bind to VIP receptors in many different human tissues. One of these, helodermin, has been shown to inhibit the growth of lung cancer.[28][29]

Toxins and drug research

The constituents of the H. suspectum venom that have received the most attention from researchers are the bioactive peptides, including helodermin, helospectin, exendin-3, and exendin-4.[30] Exendin-4, which is specific for H. suspectum, has formed the basis of a class of medications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, known as Glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists.

In 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the drug exenatide (marketed as Byetta) for the management of type 2 diabetes. It is an extravagantly, synthetic blueprint of the protein exendin-4, isolated from the Gila monster's venom.[31][32] In a three-year study with people with type 2 diabetes, exenatide showed healthy sustained glucose levels. The effectiveness is because the lizard protein is 53% identical to glucagon-like peptide-1 analog (GLP-1), a hormone released from the human digestive tract that helps to regulate insulin and glucagon. Using a sophisticated injection formula with sustained release of the drug the lizard protein remains effective much longer than the human hormone, This helps diabetics keep their blood glucose levels under control for a week by a single injection. Exenatide also slows the emptying of the stomach and causes a decrease in appetite, contributing to weight loss.[33]

Life cycle

The Gila monster emerges from brumation* in early March. H. suspectum sexually matures at four to five years old. It mates in April and May.[2] The male initiates courtship by flicking his tongue to search for the female's scent. If the female rejects his advances, she will bite him and chase him away. When successful, copulation has been observed in captivity to last from 15 minutes to as two and a half hours. There is only a single record of a try of mating outside of a shelter.[18] The female lays eggs at the end of May into June using e. g. abandoned nests of pack rats. A clutch may consist of up to six (rarely up to eight) eggs.[2][11] The incubation in captivity lasts about five months, depending on the incubation temperature. The hatchlings are about 16 cm (6.3 in) long and can bite and inject venom already upon hatching.

The egg development and hatching time of youngsters in the wild has been a subject of ongoing speculations. The first model stated that youngsters hatch in fall and stay underground.The second theory postulated a nearly developed embryo remains inside the egg over winter and hatches in spring. hatchlings (weight about 35 gms) and are observed at the end of April up to early June.

These discussions finally came to an abrupt, unexpected end, when on October 28 th., 2016, a backhoe was digging at the outer walls of a house in a suburb of northern Tucson, AZ. The backhoe extracted a nest of Heloderma suspectum with five little individuals in the process of hatching. Now we know, that the Gila hatches at about the end of October and then immediately proceeds into hibernation without showing up above the ground surface.[13] They will show up on the surface during May through June the following year when prey should be again quite abundant.

In summer Gila monsters gradually spend less time on the surface to avoid the hottest part of the season; occasionally they may be active at night. Females that have laid eggs are exhausted and skinny, fighting for survival, and have to spend extra efforts to “reconstitute”. The brumation* of Gila monsters begins in October.[2] Lucky ones may live up to 40 years in the wild,

* Brumation is defined as the hibernation for “cold blooded” animals. These ektotherms have to rely on their environment to regulate their body temperature, unlike hibernators who are in deep sleep and do not move at all. Gila monsters might move on warm winter days in front of their shelters to “soak up” some sun.

Little is known about the social behavior of H. suspectum, but they have been observed engaging in male-male combat, in which the dominant male lies on top of the subordinate one and pins it with its front and hind limbs. While fighting both lizards arch their bodies, pushing against each other and twisting around in an effort to gain the dominant position. A “wrestling match” ends when the pressure exert their forces, although bouts may be repeated.[24] These bouts are typically observed in the mating season. It is assumed that males with greater strength and endurance enjoy greater reproductive success.[2] Although the Gila monster has a low metabolism and one of the lowest lizard sprint speeds, it has one of the highest aerobic scope values (the increase in oxygen consumption from rest to maximum metabolic exertion) among lizards, allowing them to engage in intense aerobic activity for a sustained period of time.

Conservation status

Gila monsters are listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.[1]

In 1952, the Gila monster became the first venomous animal to be given legal protection.[34] Now Gila monsters are protected in all states of their distribution. Gila monsters are listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN, its international trade is regulated in appendix II B in the CITES.

Relocation

Possibly the greatest threat to the continued existence of helodermatids is the man-made destruction of their habitat as the land is developed for construction or to create more cultivable land.[35] Gila monsters found in these situations and relocated – with best intentions – up to 1.2 kilometers away return to where they were found within 2 months and at great effort. This is up to 5 times the normal energy use than if they hadn’t been removed, which uses up their energy stores unnecessarily. The same is true for animals relocated to appropriate habitats. Besides this, they also become more exposed to predators. Therefore, the process of simple relocation is “naïve” and potentially dangerous for both the relocated animals and existing populations and for the inhabitants of the region where the resettlement is taking place. If relocating the lizards further away, it is assumed they might be totally disoriented and thus their survival is still very questionable. A more successful strategy would be, for example, if the new “settlers” were offered intensive education about this species (e.g., “limited” toxicity, lifestyle) with the aim of tolerating the reptile or even being proud of having this unique “roommate” in your own neighborhood.[34]

In 1963, the San Diego Zoo became the first zoo to successfully breed Gila monsters in captivity.[36] In the last two decades experienced breeders have shared their knowledge and expertise to give advice to other herpetologists on overcoming the difficulties in Heloderma reproduction under human care.[11][37][38]

Relationship with humans

Though the Gila monster is venomous, in having laggard movement, it poses little threat to humans. However, it has a fearsome reputation and is often killed by humans. Myths that have formed about the Gila monster include that the animal's breath is toxic enough to kill humans, that it can spit venom like a spitting cobra and that it can leap several feet in the air to attack,[36] and that the Gila monster did not have an anus and therefore expelled waste from its mouth, the source of its venom and "fetid breath". (Note: The venom in fact has an intensive, specific smell.[11]) Among Native American tribes, the Gila monster had a mixed standing. The Apache believed its breath could kill a man, and the Tohono O'Odham and the Pima believed it possessed a spiritual power that could cause sickness. In contrast, the Seri and the Yaqui believed the Gila monster's hide had healing properties.

The Gila monster starred as a monster in the film The Giant Gila Monster (though the titular monster was actually portrayed by a Mexican beaded lizard).[39] It played a minor role in the motion picture The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. In Brock Brower's 1971 novel The Late Great Creature fictional horror movie star Simon Moro is presented as famous for playing the reptilian werewolf-like Gila Man. The 2011 animated film Rango featured a Gila monster as an old west outlaw named Bad Bill, voiced by Ray Winstone.[40]

The Gila monster has also seen usage as a mascot and state symbol. The official mascot of Eastern Arizona College located in Thatcher, Arizona, is Gila Hank, a gun-toting, cowboy-hat-wearing Gila monster. In 2017, the Vegas Golden Knights selected a Gila monster, named Chance, as the official mascot.[41] In 2019, the state of Utah made the Gila monster its official state reptile.[42]