The harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena)

The harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena)

Porpoises range in size from the vaquita, at 1.4 metres (4 feet 7 inches) in length and 54 kilograms (119 pounds) in weight, to the Dall's porpoise, at 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) and 220 kg (490 lb). Several species exhibit sexual dimorphism

in that the females are larger than males. They have streamlined bodies

and two limbs that are modified into flippers. Porpoises use echolocation as their primary sensory system.

Some species are well adapted for diving to great depths. As all

cetaceans, they have a layer of fat, or blubber, under the skin to keep

them warm in cold water.

Porpoises are abundant and found in a multitude of environments, including rivers (finless porpoise), coastal and shelf waters (harbour porpoise, vaquita) and open ocean (Dall's porpoise and spectacled porpoise), covering all water temperatures from tropical (Sea of Cortez, vaquita) to polar (Greenland, harbour porpoise).

Porpoises feed largely on fish and squid, much like the rest of the

odontocetes. Little is known about reproductive behaviour. Females may

get one calf every year under favourable conditions.[2][3]

Calves are typically born in the spring and summer months and remain

dependent on the female until the following spring. Porpoises produce

ultrasonic clicks, which are used for both navigation (echolocation) and social communication. In contrast to many dolphin species, porpoises do not form large social groups.

Porpoises were, and still are, hunted by some countries by means of drive hunting. Larger threats to porpoises include extensive bycatch in gill nets, competition for food from fisheries, and marine pollution, in particular heavy metals and organochlorides. The vaquita

is nearly extinct due to bycatch in gill nets, with a predicted

population of fewer than a dozen individuals. Since the extinction of

the baiji, the vaquita

is considered the most endangered cetacean. Some species of porpoises

have been and are kept in captivity and trained for research, education

and public display.

Taxonomy and evolution

Porpoises, along with whales and dolphins, are descendants of land-living ungulates (hoofed animals) that first entered the oceans around 50 million years ago (Mya). During the Miocene (23 to 5 Mya), mammals were fairly modern, meaning they seldom changed physiologically

from the time. The cetaceans diversified, and fossil evidence suggests

porpoises and dolphins diverged from their last common ancestor around

15 Mya. The oldest fossils are known from the shallow seas around the

North Pacific, with animals spreading to the European coasts and

Southern Hemisphere only much later, during the Pliocene.[4]

Recently discovered hybrids between male harbour porpoises and female Dall's porpoises indicate the two species may actually be members of the same genus.[8]

Biology

Anatomy

Porpoises have a bulbous head, no external ear flaps, a non-flexible

neck, a torpedo shaped body, limbs modified into flippers, and a tail

fin. Their skull has small eye orbits, small, blunt snouts, and eyes

placed on the sides of the head. Porpoises range in size from the 1.4 m

(4 ft 7 in) and 54 kg (119 lb) Vaquita[9] to the 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) and 220 kg (490 lb) Dall's porpoise.[10]

Overall, they tend to be dwarfed by other cetaceans. Almost all species

have female-biased sexual dimorphism, with the females being larger

than the males,[11][12] although those physical differences are generally small; one exception is Dall's porpoise.[13][14]

Odontocetes possess teeth with cementum cells overlying dentine cells. Unlike human teeth, which are composed mostly of enamel

on the portion of the tooth outside of the gum, whale teeth have

cementum outside the gum. Porpoises have a three-chambered stomach,

including a fore-stomach and fundic and pyloric chambers.[15] Porpoises, like other odontocetes, possess only one blowhole.[12] Breathing involves expelling stale air from the blowhole, forming an upward, steamy spout, followed by inhaling fresh air into the lungs.[12][16] All porpoises have a thick layer of blubber.

This blubber can help with insulation from the harsh underwater

climate, protection to some extent as predators would have a hard time

getting through a thick layer of fat, and energy for leaner times.

Calves are born with only a thin layer of blubber, but rapidly gain a

thick layer from the milk, which has a very high fat content.

Locomotion

Porpoises

have two flippers on the front and a tail fin. Their flippers contain

four digits. Although porpoises do not possess fully developed hind

limbs, they possess discrete rudimentary appendages, which may contain

feet and digits.[citation needed]

Porpoises are fast swimmers in comparison to seals, which typically

cruise at 9–28 km/h (5–15 kn). The fusing of the neck vertebrae, while

increasing stability when swimming at high speeds, decreases

flexibility, making it impossible for them to turn their head.[17]

When swimming, they move their tail fin and lower body up and down,

propelling themselves through vertical movement, while their flippers

are mainly used for steering. Flipper movement is continuous. Some

species log out of the water, which may allow them to travel faster, and sometimes they porpoise

out of the water, meaning jump out of the water. Their skeletal anatomy

allows them to be fast swimmers. They have a very well defined and

triangular dorsal fin,

allowing them to steer better in the water. Unlike their dolphin

counterparts, they are adapted for coastal shores, bays, and estuaries.[12][18]

Senses

The porpoise ear has specific adaptations to the marine environment. In humans, the middle ear works as an impedance equaliser between the outside air's low impedance and the cochlear

fluid's high impedance. In whales, and other marine mammals, there is

no great difference between the outer and inner environments. Instead of

sound passing through the outer ear to the middle ear, porpoises

receive sound through the throat, from which it passes through a

low-impedance fat-filled cavity to the inner ear.[19]

The porpoise ear is acoustically isolated from the skull by air-filled

sinus pockets, which allow for greater directional hearing underwater.[20] Odontocetes send out high frequency clicks from an organ known as a melon.

This melon consists of fat, and the skull of any such creature

containing a melon will have a large depression. The large bulge on top

of the porpoises head is caused by the melon.[12][21][22][23]

The porpoise eye is relatively small for its size, yet they do

retain a good degree of eyesight. As well as this, the eyes of a

porpoise are placed on the sides of its head, so their vision consists

of two fields, rather than a binocular view like humans have. When

porpoises surface, their lens and cornea correct the nearsightedness

that results from the refraction of light; their eyes contain both rod and cone

cells, meaning they can see in both dim and bright light. Porpoises do,

however, lack short wavelength sensitive visual pigments in their cone

cells indicating a more limited capacity for colour vision than most

mammals.[24]

Most porpoises have slightly flattened eyeballs, enlarged pupils (which

shrink as they surface to prevent damage), slightly flattened corneas

and a tapetum lucidum;

these adaptations allow for large amounts of light to pass through the

eye and, therefore, they are able to form a very clear image of the

surrounding area.[21]

The olfactory lobes are absent in porpoises, suggesting that they have no sense of smell.[21]

Porpoises are not thought to have a good sense of taste, as their

taste buds are atrophied or missing altogether. However, some have

preferences between different kinds of fish, indicating some sort of

attachment to taste.[21]

Unlike most animals, porpoises are conscious breathers. All mammals

sleep, but porpoises cannot afford to become unconscious for long

because they may drown. While knowledge of sleep in wild cetaceans is

limited, porpoises in captivity have been recorded to sleep with one

side of their brain at a time, so that they may swim, breathe

consciously, and avoid both predators and social contact during their

period of rest.

[25]

This means that the brain hemispheres take turns alternating

between slow wave sleep and being awake. While one hemisphere displays

slow waves, the other displays wake patterns on an electroencephalogram.

It has been suggested that the brainstem controls this activity. All

the while, porpoises also employ a minimal amount of suppressed REM

sleep while swimming.

The same neural systems that regulate sleep in bihemispheric

mammals are used in harbor porpoises. Cetaceans use many of the same

neurotransmitters that other mammals use, although they have a

significantly higher number. Although the way porpoises sleep is

different from other mammals, they use the same neural mechanisms and

pathways. One key difference is that porpoises seem to inhibit REM sleep

more than most mammals, likely to prevent losing muscle tone and thus

decreasing the risk of drowning or suffering from hypothermia. Porpoises

differ from other mammals in terms of the neurons that regulate their

sleep-wake cycle, however, the sleep-wake cycle overall is surprisingly

similar to other mammals. This shows that despite differences in

sleeping patterns, the sleep wake mechanism is conserved across species.

The anatomy of the cetacean brain varies slightly from that of other

mammals, with the area governing sleep-wake cycles (caudal to the

posterior commissures) being significantly larger.

It is difficult to use traditional methods to determine whether a

porpoise is sleeping, since half of the brain is awake at any given

time. Parabolic dives have been shown to potentially be correlated to

sleeping periods in porpoises, with decreased bioacoustics being

transmitted during these periods. This means that during parabolic

dives, porpoises generally do not employ echolocation clicks (about

fifty percent of the time). This may be related to the side of the brain

that is asleep. For instance, the left hemisphere signals to the right

side of the brain, which controls the production of echolocation clicks.

Thus, when the left side of the brain is asleep, echolocation cannot be

produced.

Along with using less bioacoustics, porpoises roll less, use a

lower vertical descent rate, and are overall less active while

performing parabolic dives. Parabolic dives have shown to be of shallow

depth and use a low amount of energy. These are different behaviors than

the those displayed during foraging dives. Moreover, these behaviors

are consistent with stereotypical sleeping behavior.

Interestingly, parabolic dives are more common during the daytime

than during the nighttime and only take up a small amount of a wild

porpoise's total time, as opposed to the time spent sleeping in other

mammals. Meanwhile, captive cetaceans have been shown to spend up to

fifty percent of their time sleeping and up to sixty-six percent of

their time resting. A thought that deserves further consideration is

that wild porpoises spend a significant fraction of their time near the

surface of the water, and it is difficult to determine if this time is

being spent resting or sleeping.

Behaviour

Life cycle

Porpoises are fully aquatic creatures. Females deliver a single calf after a gestation period

lasting about a year. Calving takes place entirely under water, with

the foetus positioned for tail-first delivery to help prevent drowning.

Females have mammary glands, but the shape of a newborn calf's mouth

does not allow it to obtain a seal around the nipple— instead of the

calf sucking milk, the mother squirts milk into the calf's mouth.[26]

This milk contains high amounts of fat, which aids in the development

of blubber; it contains so much fat that it has the consistency of

toothpaste. The calves are weaned at about 11 months of age. Males play

no part in rearing calves. The calf is dependent for one to two years,

and maturity occurs after seven to ten years, all varying between

species. This mode of reproduction produces few offspring, but increases the probability of each one surviving.[13]

Porpoises eat a wide variety of creatures. The stomach contents of harbour porpoises suggests that they mainly feed on benthic fish, and sometimes pelagic fish. They may also eat benthic invertebrates. In rare cases, algae, such as Ulva lactuca, is consumed. Atlantic porpoises are thought to follow the seasonal migration of bait fish, like herring, and their diet varies between seasons. The stomach contents of Dall's porpoises reveal that they mainly feed on cephalopods and bait fish, like capelin and sardines. Their stomachs also contained some deep-sea benthic organisms.[18]

The finless porpoise is known to also follow seasonal migrations. It is known that populations in the mouth of the Indus River migrate to the sea from April through October to feed on the annual spawning of prawns. In Japan, sightings of small pods of them herding sand lance onto shore are common year-round.[18]

Little is known about the diets of other species of porpoises. A

dissection of three Burmeister's porpoises shows that they consume

shrimp and euphausiids (krill). A dissection of a beached Vaquita showed remains of squid and grunts. Nothing is known about the diet of the spectacled porpoise.[18]

Interactions with humans

Research history

In Aristotle's

time, the 4th century BCE, porpoises were regarded as fish due to their

superficial similarity. Aristotle, however, could already see many

physiological and anatomical similarities with the terrestrial

vertebrates, such as blood (circulation), lungs, uterus and fin anatomy.[citation needed]

His detailed descriptions were assimilated by the Romans, but mixed

with a more accurate knowledge of the dolphins, as mentioned by Pliny the Elder

in his "Natural history". In the art of this and subsequent periods,

porpoises are portrayed with a long snout (typical of dolphins) and a

high-arched head. The harbour porpoise was one of the most accessible species for early cetologists,

because it could be seen very close to land, inhabiting shallow coastal

areas of Europe. Much of the findings that apply to all cetaceans were

first discovered in porpoises.[27]

One of the first anatomical descriptions of the airways of the whales

on the basis of a harbor porpoise dates from 1671 by John Ray.[28][29]

It nevertheless referred to the porpoise as a fish, most likely not in

the modern-day sense, where it refers to a zoological group, but the

older reference as simply a creature of the sea (cf. for example star-fish, cuttle-fish, jelly-fish and whale-fish).

In captivity

Harbour porpoises have historically been kept in captivity, under the

assumption that they would fare better than their dolphin counterparts

due to their smaller size and shallow-water habitats. Up until the

1980s, they were consistently short-lived.[18][30] Harbour porpoises have a very long captive history, with poorly documented attempts as early as the 15th century,[18] and better documented starting in the 1860s and 1870s in London Zoo, the now-closed Brighton Aquarium & Dolphinarium, and a zoo in Germany.[30][31] At least 150 harbour porpoises have been kept worldwide, but only about 20 were actively caught for captivity.[18]

The captive history is best documented from Denmark where about 100

harbour porpoises have been kept, most in the 1960s and 1970s. All but

two were incidental catches in fishing nets or strandings. Nearly half

of these died within a month of diseases caught before they were

captured or from damage sustained during capture. Up until 1984, none

lived for more than 14 months.[18][30] Attempts of rehabilitation seven rescued individuals in 1986 only resulted in three that could be released 6 months later.[18]

Very few have been brought into captivity later, but they have lived

considerably longer. In recent decades the only place keeping the

species in Denmark is the Fjord & Bælt Centre, where three rescues

have been kept, along with their offspring. Among the three rescues, one

(father of world's first harbour porpoise born in captivity) lived for

20 years in captivity and another 15 years, while the third (mother of

first born in captivity) is still alive in 2021 after 23 years.[32][33][failed verification] This is older than the typical age reached in the wild, which is 14 years or less.[33][34][35]

Very few harbour porpoises have been born in captivity. Historically,

harbour porpoises were often kept singly and those who were together

often were not mature or of the same sex.[18] Disregarding one born more than 100 years ago that was the result of a pregnant female being brought into captivity,[18] the world's first full captive breeding was in 2007 in the Fjord & Bælt Centre, followed by another in 2009 in the Dolfinarium Harderwijk, the Netherlands.[36] In addition to the few kept in Europe, harbour porpoise were displayed at the Vancouver Aquarium (Canada) until recently. This was a female that had beached herself onto Horseshoe Bay in 2008 and a male that had done the same in 2011.[37][38] They died in 2017 and 2016 respectively.[39][40]

Finless porpoises have commonly been kept in Japan, as well as

China and Indonesia. As of 1984, ninety-four in total had been in

captivity in Japan, eleven in China, and at least two in Indonesia. As

of 1986, three establishments in Japan had bred them, and there had been

five recorded births. Three calves died moments after their birth, but

two survived for several years.[18]

This breeding success, combined with the results with harbour porpoise

in Denmark and the Netherlands, proved that porpoises can be

successfully bred in captivity, and this could open up new conservation

options.[18][41] The reopened Miyajima Public Aquarium (Japan) houses three finless porpoises.[42] As part of an attempt of saving the narrow-ridged (or Yangtze) finless porpoise,

several are kept in the Baiji Dolphinarium in China. After having been

kept in captivity for 9 years, the first breeding happened in 2005.[43]

Small numbers of Dall's porpoises have been kept in captivity in

both the United States and Japan, with the most recent being in the

1980s. The first recorded instance of a Dall's taken for an aquarium was

in 1956 captured off Catalina Island in southern California.[44]

Dall's porpoises consistently failed to thrive in captivity. These

animals often repeatedly ran into the walls of their enclosures, refused

food, and exhibited skin sloughing. Almost all Dall's porpoises introduced to aquaria died shortly after, typically within days.[18][45] Only two have lived for more than 60 days: a male reached 15 months at Marineland of the Pacific and another 21 months at a United States Navy facility.[45]

As part of last-ditch effort of saving the extremely rare vaquita

(the tiny remaining population is rapidly declining because of bycatch

in gillnets), there have been attempts of transferring some to

captivity.[41][46]

The first and only caught for captivity were two females in 2017. Both

became distressed and were rapidly released, but one of them died in the

process.[47][48] Soon after the project was abandoned.[48]

Only a single Burmeister's porpoise and a single spectacled porpoise have been kept in captivity. Both were stranded individuals that only survived a few days after their rescue.[18][49]

Threats

Porpoises and other smaller cetaceans have traditionally been hunted

in many areas for their meat and blubber. A dominant hunting technique

is drive hunting, where a pod of animals is driven together with boats

and usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by

closing off the route to the ocean with other boats or nets. This type

of fishery for harbour porpoises is well documented from the Danish Straits, where it occurred regularly until the end of the 19th century,[50] and picked up again during World war I and World War II. The Inuit in the Arctic hunt harbour porpoises by shooting and drive hunt for Dall's porpoise

still takes place in Japan. The number of individuals taken each year

is in the thousands, although a quota of around 17,000 per year is in

effect today[51] making it the largest direct hunt of any cetacean species in the world[52] and the sustainability of the hunt has been questioned.[53][54]

Porpoises are highly affected by bycatch. Many porpoises, mainly the vaquita, are subject to great mortality due to gillnetting.

Although it is the world's most endangered marine cetacean, the vaquita

continues to be caught in small-mesh gillnet fisheries throughout much

of its range. Incidental mortality caused by the fleet of El Golfo de

Santa Clara was estimated to be at around 39 vaquitas per year, which is

over 17% of the population size.[55]

Harbour porpoises also suffer drowning by gillnetting, but on a less

threatening scale due to their high population; their mortality rate per

year increases a mere 5% due to this.[56]

The fishing market, historically has always had a porpoise bycatch. Today, the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 has enforced the use of safer fishing equipment to reduce bycatch.[57]

Porpoises are very sensitive to anthropogenic disturbances,[58] and are keystone species, which can indicate the overall health of the marine environment.[58]

Populations of harbor porpoises in the North and Baltic Seas are under

increasing pressure from anthropogenic causes such as offshore

construction, ship traffic, fishing, and military exercises.[59] Increasing pollution is a serious problem for marine mammals. Heavy metals and plastic waste

are not biodegradable, and sometimes cetaceans consume these hazardous

materials, mistaking them for food items. As a result, the animals are

more susceptible to diseases and have fewer offspring.[60] Harbour porpoises from the English Channel were found to have accumulated heavy metals.[58]

The military and geologists employ strong sonar and produce an increases in noise in the oceans. Marine mammals that make use of biosonar

for orientation and communication are not only hindered by the extra

noise, but may race to the surface in panic. This may lead to a bubbling

out of blood gases, and the animal then dies because the blood vessels

become blocked, so-called decompression sickness.[61] This effect, of course, only occurs in porpoises that dive to great depths, such as Dall's porpoise.[62]

Additionally, civilian vessels produce sonar waves to measure the

depth of the body of water in which they are. Similar to the navy, some

boats produce waves that attract porpoises, while others may repel

them. The problem with the waves that attract is that the animal may be

injured or even killed by being hit by the vessel or its propeller.[63]

The harbour porpoise, spectacled porpoise, Burmeister's porpoise, and Dall's porpoise are all listed on Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).[64][65] In addition, the Harbour porpoise is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS), the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area

(ACCOBAMS) and the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the

Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and

Macaronesia.[66] Their conservation statuses are either at least concern or data deficient.[67]

As of 2014, only 505 Yangtze finless porpoises

remained in the main section of the Yangtze, with an alarming

population density in Ezhou and Zhenjiang. While many threatened species

decline rate slows after their classification, population decline rates

of the porpoise are actually accelerating. While population decline

tracked from 1994 to 2008 has been pegged at a rate of 6.06% annually,

from 2006 to 2012, the porpoise population decreased by more than half.

Finless porpoise population decrease of 69.8% in just a 22-year span

from 1976 to 2000. 5.3%.[68]

A majority of factors of this population decline are being driven by

the massive growth in Chinese industry since 1990 which caused increased

shipping and pollution and ultimately environmental degradation.[69] Some of these can be seen in damming of the river as well as illegal fishing

activity. To protect the species, China's Ministry of Agriculture

classified the species as being National First Grade Key Protected Wild

Animal, the strictest classification by law, meaning it is illegal to

bring harm to a porpoise. Protective measures in the Tian-e-Zhou Oxbow Nature Reserve has increased its population of porpoises from five to forty in 25 years. The Chinese Academy of Science's Wuhan Institute of Hydrobiology has been working with the World Wildlife Fund

to ensure the future for this subspecies, and have placed five

porpoises in another well-protected area, the He-wang-miao oxbow.[70]

Five protected natural reserves have been established in areas of the

highest population density and mortality rates with measures being taken

to ban patrolling and harmful fishing gear in those areas. There have

also been efforts to study porpoise biology to help specialize

conservation through captivation breeding. The Baiji Dolphinarium, was

established in 1992 at the Institute of Hydrobiology of the Chinese

Academy of Sciences in Wuhan which allowing the study of behavioral and

biological factors affecting the finless porpoise, specifically breeding

biology like seasonal changes in reproductive hormones and breeding

behavior.[71]

Because vaquitas are indigenous to the Gulf of California, Mexico is leading conservation efforts with the creation of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita

(CIRVA), which has tried to prevent the accidental deaths of vaquitas

by outlawing the use of fishing nets within the vaquita's habitat.[72] CIRVA has worked together with the CITES, the Endangered Species Act, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) to nurse the vaquita population back to a point at which they can sustain themselves.[73]

CIRVA concluded in 2000 that between 39 and 84 individuals are killed

each year by such gillnets. To try to prevent extinction, the Mexican

government has created a nature reserve covering the upper part of the

Gulf of California and the Colorado River delta. They have also placed a temporary ban on fishing, with compensation to those affected, that may pose a threat to the vaquita.[74

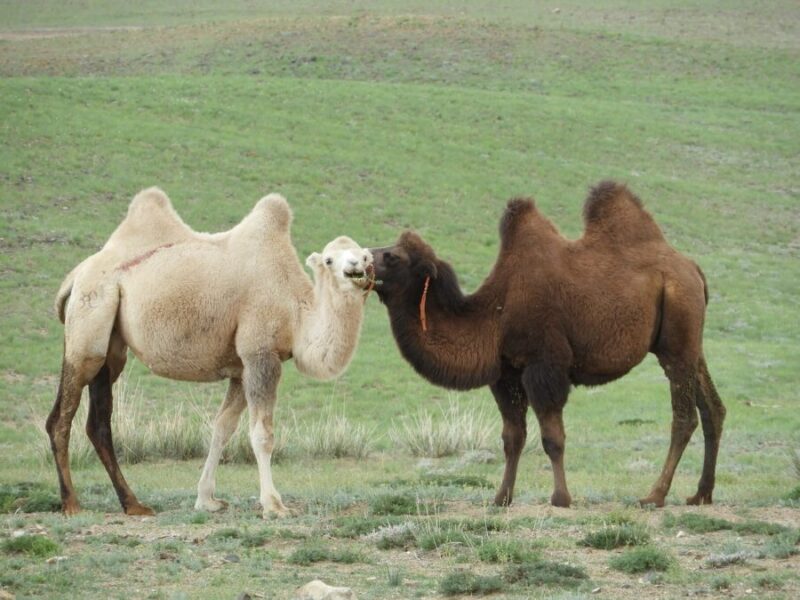

Wild Bactrian camel

Wild Bactrian camel

The

The