The trogons and quetzals are birds in the order Trogoniformes /troʊˈɡɒnɪfɔːrmiːz/ which contains only one family, the Trogonidae. The family Trogonidae contains 46 species in seven genera. The fossil record of the trogons dates back 49 million years to the Early Eocene. They might constitute a member of the basal radiation of the order Coraciiformes and order Passeriformes[1] or be closely related to mousebirds and owls.[2][3] The word trogon is Greek for "nibbling" and refers to the fact that these birds gnaw holes in trees to make their nests.

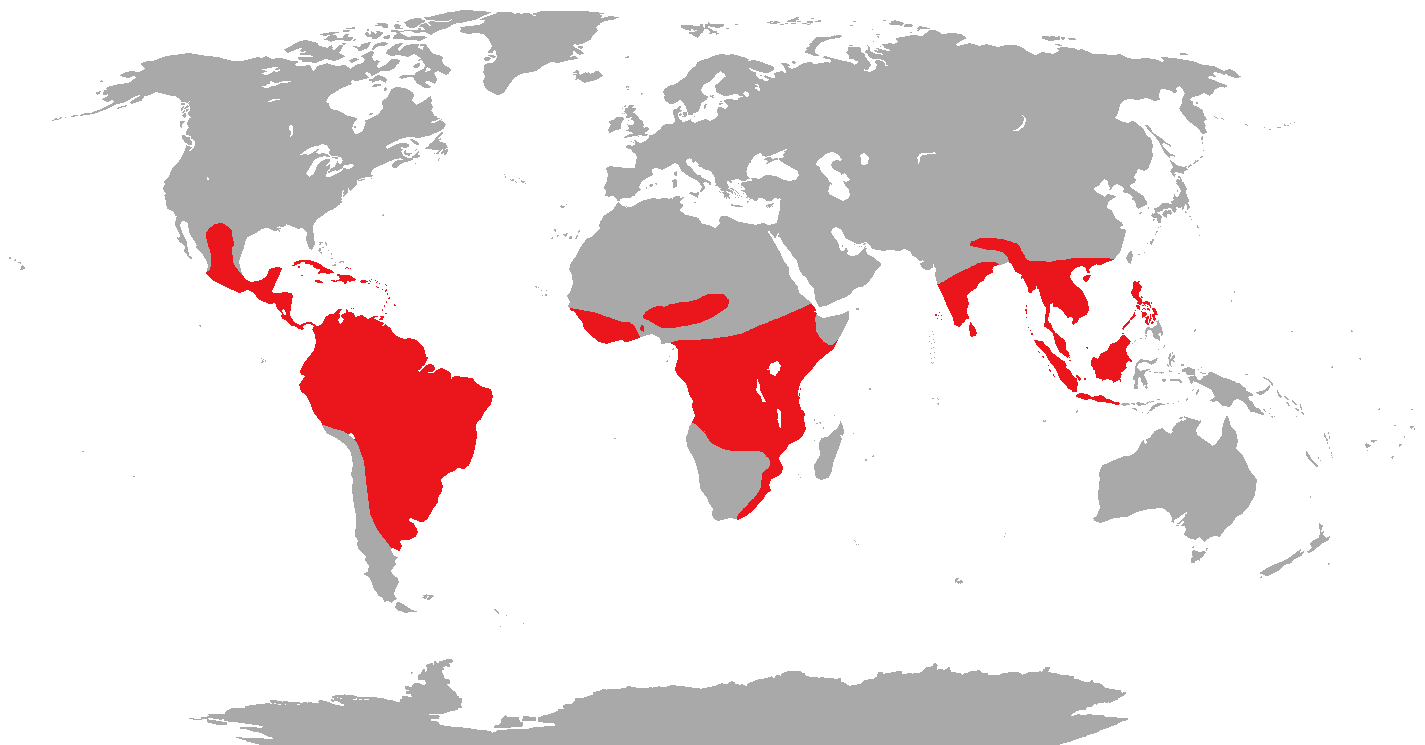

Trogons are residents of tropical forests worldwide. The greatest diversity is in the Neotropics, where four genera, containing 24 species, occur. The genus Apaloderma contains the three African species. The genera Harpactes and Apalharpactes, containing twelve species, are found in southeast Asia.[4]

They feed on insects and fruit, and their broad bills and weak legs reflect their diet and arboreal habits. Although their flight is fast, they are reluctant to fly any distance. Trogons are generally not migratory, although some species undertake partial local movements. Trogons have soft, often colourful, feathers with distinctive male and female plumage. They are the only type of animal with a heterodactyl toe arrangement. They nest in holes dug into trees or termite nests, laying 2–4 white or pastel-coloured eggs.

Evolution and taxonomy

The position of the trogons within the class Aves has been a long-standing mystery.[4] A variety of relations have been suggested, including the parrots, cuckoos, toucans, jacamars and puffbirds, rollers, owls and nightjars. More recent morphological and molecular evidence has suggested a relationship with the Coliiformes. The unique arrangement of the toes on the foot (see morphology and flight) has led many to consider the trogons to have no close relatives; to place them in their own order, possibly with the similarly atypical mousebirds as their closest relatives.

The earliest formally described fossil specimen is a cranium from the Fur Formation Lower Eocene in Denmark (54 mya).[5] Other trogoniform fossils have been found in the Messel pit deposits from the mid-Eocene in Germany (49 mya),[6] and in Oligocene and Miocene deposits from Switzerland and France respectively. The oldest New World fossil of a trogon is from the comparatively recent Pleistocene (less than 2.588 mya).

The family had been thought to have an Old World origin[7] notwithstanding the current richness of the family, which is more diverse in the Neotropical New World. DNA evidence seemed to support an African origin for the trogons, with the African genus Apaloderma seemingly basal in the family, and the other two lineages, the Asian and American, breaking off between 20–36 million years ago. More recent studies[8][9][10] show that the DNA evidence gives contradictory results concerning the basal phylogenetic relationships; so it is currently unknown if all extant trogons are descended from an African or an American ancestor or neither.

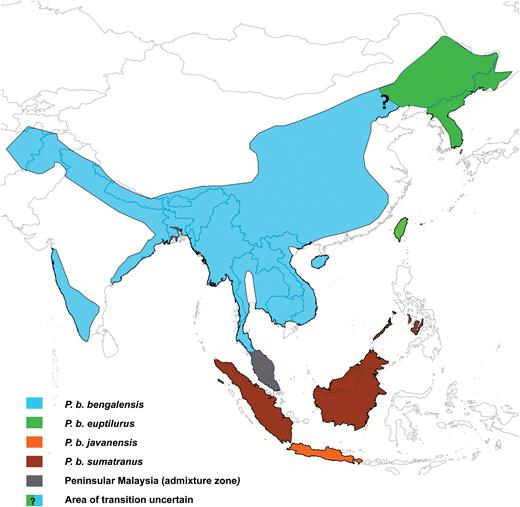

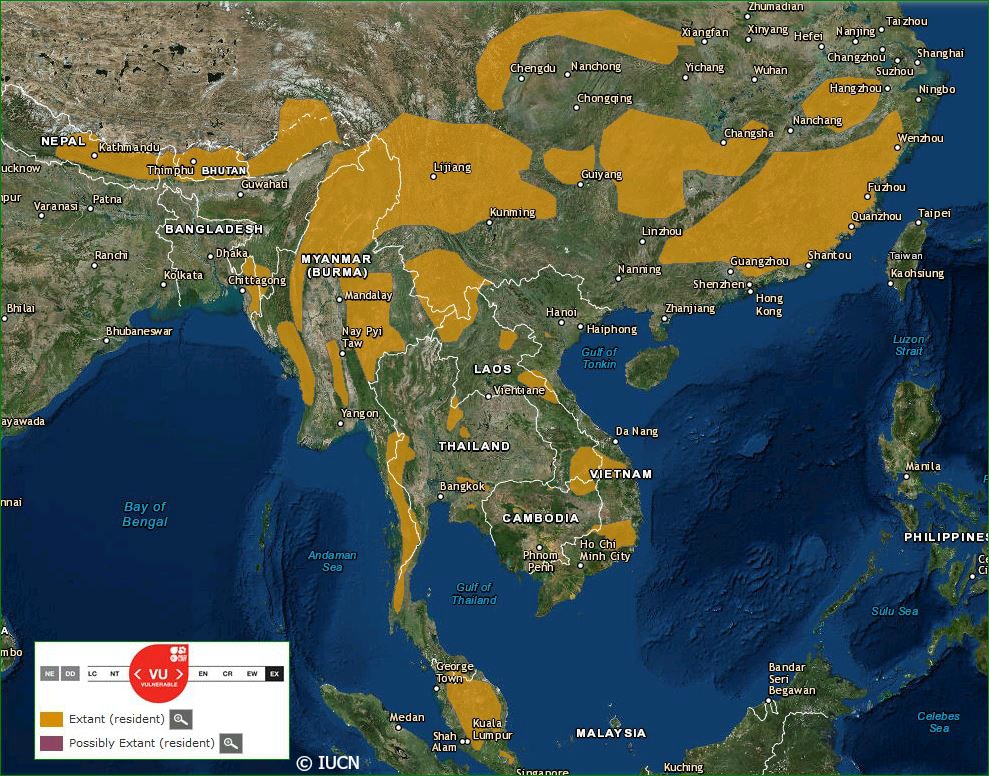

The trogons are split into three subfamilies, each reflecting one of these splits, Aplodermatinae is the African subfamily and contains a single genus, Apaloderma. Harpactinae is the Asian subfamily and contains two genera, Harpactes and Apalharpactes. Apalharpactes, consisting of two species in Java and Sumatra, has only recently been accepted as a separate genus from Harpactes.[11] The remaining subfamily, the Neotropical Trogoninae, contains the remaining four genera, Trogon, Priotelus, Pharomachrus and Euptilotis.[4]

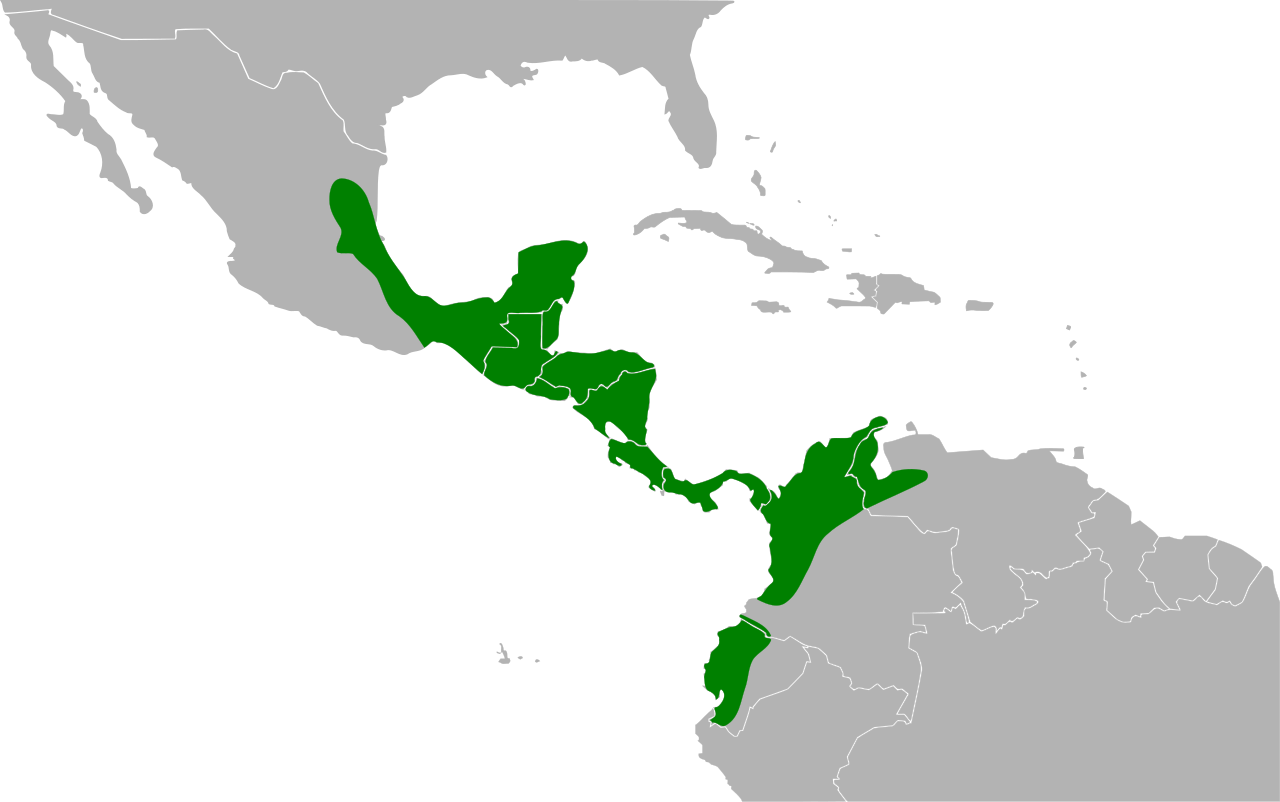

The two Caribbean species of Priotelus were formerly different ones (Temnotrogon on Hispaniola), and are extremely ancient. The two quetzal genera, Pharomachrus and Euptilotis are possibly derived from the final and most numerous genus of trogons in the Neotropics, Trogon. A 2008 study of the genetics of Trogon suggested the genus originated in Central America and radiated into South America after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama (as part of the Great American Interchange), thus making trogons relatively recent arrivals in South America.[12]

Distribution and habitat

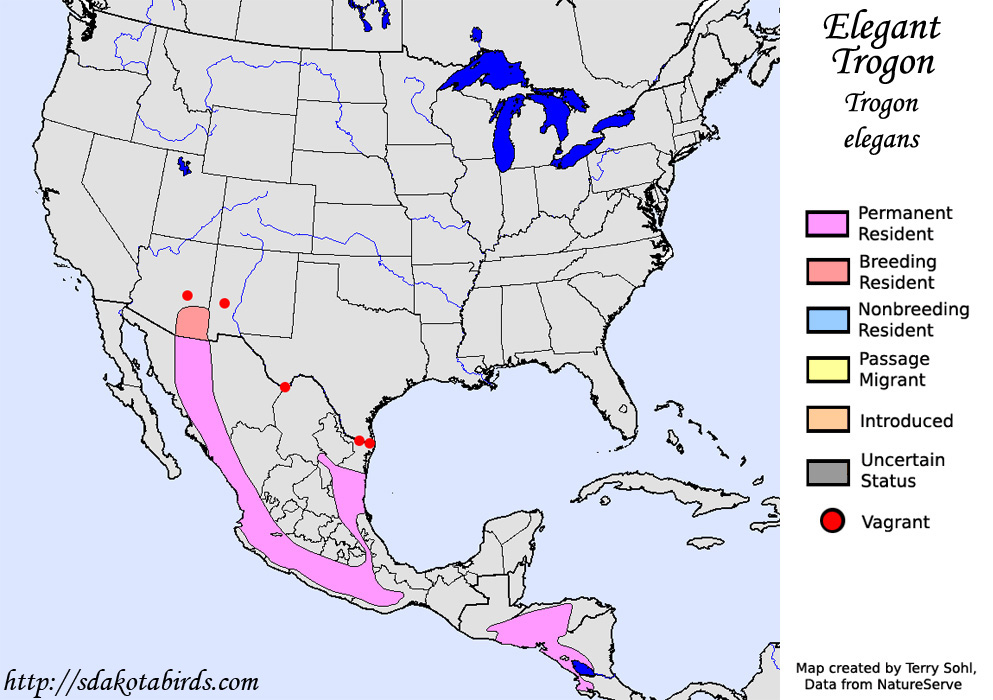

The majority of trogons are birds of tropical and subtropical forests. They have a cosmopolitan distribution in the worlds wet tropics, being found in the Americas, Africa and Asia. A few species are distributed into the temperate zone, with one species, the elegant trogon, reaching the south of the United States, specifically southern Arizona and the surrounding area. The Narina trogon of Africa is slightly exceptional in that it utilises a wider range of habitats than any other trogon, ranging from dense forest to fairly open savannah, and from the Equator to southern South Africa. It is the most widespread and successful of all the trogons. The eared quetzal of Mexico is also able to use more xeric habitats, but preferentially inhabits forests. Most other species are more restricted in their habitat, with several species being restricted to undisturbed primary forest. Within forests they tend to be found in the mid-story, occasionally in the canopy.

Some species, particularly the quetzals, are adapted to cooler montane forest. There are a number of insular species; these include a number of species found in the Greater Sundas, one species in the Philippines as well as two species endemic to Cuba and Hispaniola respectively. Outside of South East Asia and the Caribbean, however, trogons are generally absent from islands, especially oceanic ones.

Trogons are generally sedentary, with no species known to undertake long migrations. A small number of species are known to make smaller migratory movements, particularly montane species which move to lower altitudes during different seasons. This has been demonstrated using radio tracking in the resplendent quetzal in Costa Rica and evidence has been accumulated for a number of other species. The Narina trogon of Africa is thought to undertake some localised short-distance migrations over parts of its range, for example birds of Zimbabwe's plateau savannah depart after the breeding season. A complete picture of these movements is however lacking. Trogons are difficult to study as their thick tarsi (feet bones) make ringing studies difficult.

Morphology and flight

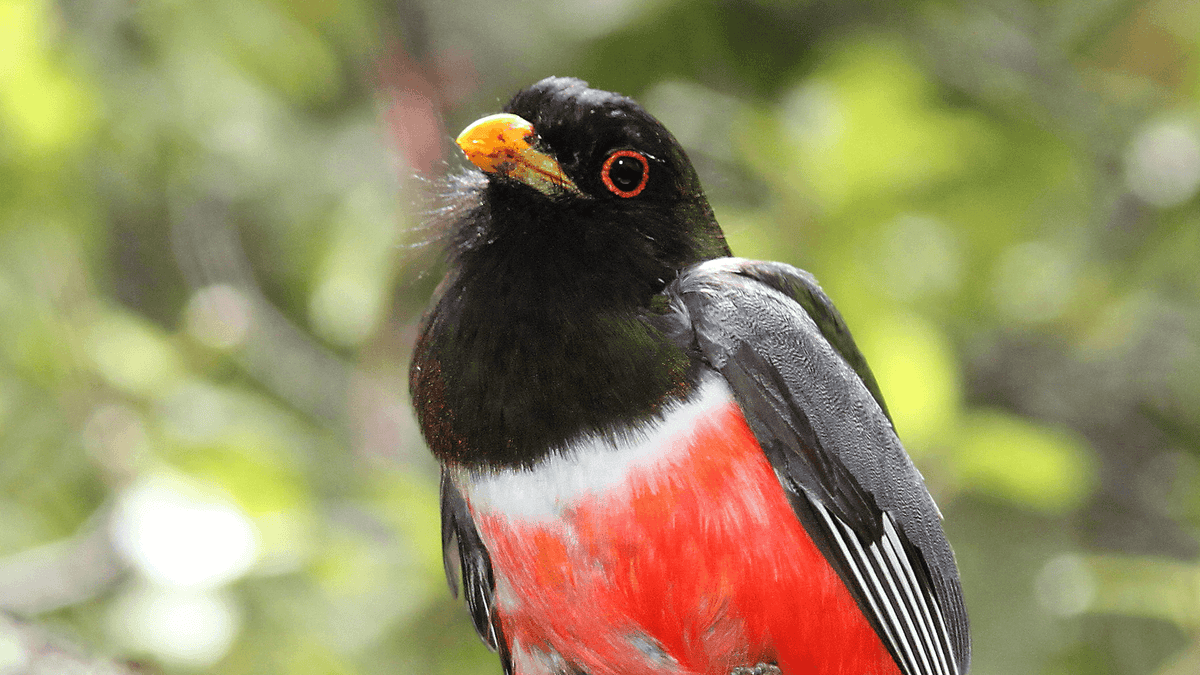

The trogons as a family are fairly uniform in appearance, having compact bodies and long tails (very long in the case of the quetzals), and short necks. Trogons range in size from the 23 cm (9.1 in), 40 g (1.4 oz) scarlet-rumped trogon to the 40 cm (16 in), 210 g (7.4 oz) resplendent quetzal (not including the male quetzal's 3-foot-long (0.91 m) tail streamers). Their legs and feet are weak and short, and trogons are essentially unable to walk beyond a very occasional shuffle along a branch. They are even incapable of turning around on a branch without using their wings. The ratio of leg muscle to body weight in trogons is only 3%, the lowest known ratio of any bird. The arrangement of toes on the feet of trogons is also unique among birds, although essentially resembling the zygodactyl's two forward two backward arrangement of parrots and other near-passerines, the actual toes are arranged with usually inner hallux being the outer hind toe, an arrangement that is referred to as heterodactylous. The strong bill is short and the gape wide, particularly in the fruit eating quetzals, with a slight hook at the end. There is also a notch at the end of the bill and many species have slight serrations in the mandibles. The skin is exceptionally tender, making preparation of study skins difficult for museum curators. The skeletons of trogons are surprisingly slender, particularly the skulls which are very thin. The plumage of many species is iridescent, although not in most of the Asian species. The African trogons are generally green on the back with red bellies. The New World trogons similarly have green or deep blue upperparts but are more varied in their lowerparts. The Asian species tend towards red underparts and brown backs.

The wings are short but strong, with the wing muscle ratio being around 22% of the body weight. In spite of the strength of their flight, trogons do not fly often or for great distances, generally flying no more than a few hundred metres at a time. Only the montane species tend to make long-distance flights. Shorter flights tend to be direct and swift, but longer flights are slightly undulating. Their flight can be surprisingly silent (for observers), although that of a few species is reportedly quite noisy.

Calls

The calls of trogons are generally loud and uncomplex, consisting of monosyllabic hoots and whistles delivered in varying patterns and sequences.[4] The calls of the quetzals and the two Caribbean genera are the most complex. Among the Asian genera the Sumatran trogon (Apalharpactes) has the most atypical call of any trogon, research has not yet established whether the closely related Javan trogon has a similar call.[11] The calls of the other Asian genus, Harpactes, are remarkably uniform. In addition to the territorial and breeding calls given by males and females during the breeding seasons, trogons have been recorded as having aggression calls given by competing males and alarm calls.

Behaviour

Trogons are generally inactive outside of infrequent feeding flights. Among birdwatchers and biologists it has been noted that "[a]part from their great beauty [they] are notorious ... for their lack of other immediately engaging qualities".[4] Their lack of activity is possibly a defence against predation; trogons on all continents have been reported to shift about on branches to always keep their less brightly coloured backs turned towards observers, while their heads, which like owls can turn through 180 degrees, keep a watch on the watcher. Trogons have reportedly been preyed upon by hawks and predatory mammals; one report was of a resplendent quetzal taken while brooding young by a margay.[13]

Diet and feeding

Trogons feed principally on insects, other arthropods, and fruit; to a lesser extent some small vertebrates such as lizards are taken.[4] Among the insect prey taken one of the more important types are caterpillars; along with cuckoos, trogons are one of the few birds groups to regularly prey upon them. Some caterpillars are known to be poisonous to trogons though, like Arsenura armida. The extent to which each food type is taken varies depending on geography and species. The three African trogons are exclusively insectivorous, whereas the Asian and American genera consume varying amounts of fruit. Diet is somewhat correlated with size, with larger species feeding more on fruit and smaller species focusing on insects.[14]

Prey is almost always obtained on the wing.[4] The most commonly employed foraging technique is a sally-glean flight, where a trogon flies from an observation perch to a target on another branch or in foliage. Once there the birds hovers or stalls and snatches the item before returning to its perch to consume the item. This type of foraging is commonly used by some types of bird to obtain insect prey; in trogons and quetzals it is also used to pluck fruit from trees. Insect prey may also be taken on the wing, with the trogon pursuing flying insects in a similar manner to drongos and Old World flycatchers. Frogs, lizards and large insects on the ground may also be pounced on from the air. More rarely some trogons may shuffle along a branch to obtain insects, insect eggs and very occasionally nestling birds. Violaceous trogons will consume wasps and wasp larvae encountered while digging nests.[15]

Breeding

Trogons are territorial and monogamous. Males will respond quickly to playbacks of their calls and will repel other members of the same species and even other hole-nesting species from around their nesting sites. Males attract females by singing,[4] and, in the case of the resplendent quetzal, undertaking display flights.[16] Some species have been observed in small flocks of 3–12 individuals prior to and sometimes during the breeding season, calling and chasing each other, but the function of these flocks is unclear.[17]

Trogons are cavity nesters. Nests are dug into rotting wood or termite nests,[4] with one species, the violaceous trogon, nesting in wasp nests.[15] Nest cavities can either be deep upward slanting tubes that lead to fully enclosed chambers, or much shallower open niches (from which the bird is visible). Nests are dug with the beak, incidentally giving the family its name. Nest digging may be undertaken by the male alone or by both sexes. In the case of nests dug into tree trunks, the wood must be strong enough not to collapse but soft enough to dig out. Trogons have been observed landing on dead tree trunks and slapping the wood with their tails, presumably to test the firmness.

The nests of trogons are thought to usually be unlined. Between two and four eggs are laid in a nesting attempt. These are round and generally glossy white or lightly coloured (buff, grey, blue or green), although they get increasingly dirty during incubation. Both parents incubate the eggs (except in the case of the bare-cheeked trogon, where apparently the male takes no part),[4] with the male taking one long incubation stint a day and the female incubating the rest of the time. Incubation seems to begin after the last egg is laid. The incubation period varies by species, usually lasting between 16–19 days. On hatching the chicks are altricial, blind and naked. The chicks acquire feathers rapidly in some of the montane species, in the case of the mountain trogon in a week, but more slowly in lowland species like the black-headed trogon, which may take twice as long. The nestling period varies by species and size, with smaller species generally taking 16 to 17 days to fledge, whereas larger species may take as long as 30 days, although 23–25 days is more typical.

Trogons and quetzals are considered to be "among the most beautiful of birds",[4] yet they are also often reclusive and seldom seen. Little is known about much of their biology, and much of what is known about them comes from the research of neotropical species by the ornithologist Alexander Skutch. Trogons are nevertheless popular birds with birdwatchers, and there is a modest ecotourism industry in particular to view quetzals in Central America.[4]

Species list

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny of genera based on Moyle (2005)[8] |

- Order Trogoniformes

- Family Trogonidae

| Image | Genus | Living Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Apaloderma Swainson, 1833 |

|

|

Apalharpactes Bonaparte, 1854 |

|

|

Harpactes Swainson, 1833 |

|

|

Priotelus G.R. Gray, 1840 |

|

|

Trogon Gould, 1836 |

|

|

Euptilotis Gould, 1858 |

|

|

Pharomachrus La Llave, 1832 |

|