The moustached tamarin (Saguinus mystax) is a New World monkey and a species of tamarin. The moustached tamarin is named for the lack of coloring in the facial hair surrounding their mouth, appearing similar to a moustache. As with all New World monkeys, the moustached tamarin is found only in areas of Central and South America.

Moustached tamarins have a lifespan of about 20 years.[citation needed] They are small, weighing 500 to 600 grams, and range in length from 30 to 92 centimeters, with adult females larger than males.[3][4]

Moustached tamarin monkeys are characterized by white, curly hair around their mouth, similar to a moustache.[5] Their face is flat with almond-like shaped eyes.[5] Their ears are furry and large, and they have long, silky, body hair.[5] They have a brownish-black body with a white moustache and white nose. They have tegula, which are claw-like nails, on each digit except their big toe.[citation needed] These claws allow them to easily cling to trees while they feed. They have conical or spatulate incisors, which are used for cutting food, and are smaller than their canines.[4] The lingual and labial sides of their incisors have a thick layer of enamel. Unlike most New World Monkeys, the moustached tamarin monkey has non-opposable thumbs and lacks a prehensile tail.[5]

Heterozygous females, which make up about 60% of the female tamarin population, have trichromatic vision, while the remaining moustached tamarin population have dichromatic vision.[3] Trichromatic vision is the capacity to see a broader range of color due to the presence of three color receptors in the retina, at the back of the eye, allowing them to distinguish between greens, blues and reds.[3] Humans, as well as most species of Old World Monkeys, have trichromatic visual abilities; however, some female New World monkeys do as well. Dichromatic vision is a form of color vision in which only two of the primary colors are perceived.[3] Trichromatic vision is an evolutionary adaptation that enables females to more easily find and identify fruit. Color vision is a contributing factor for leadership selection in troops.

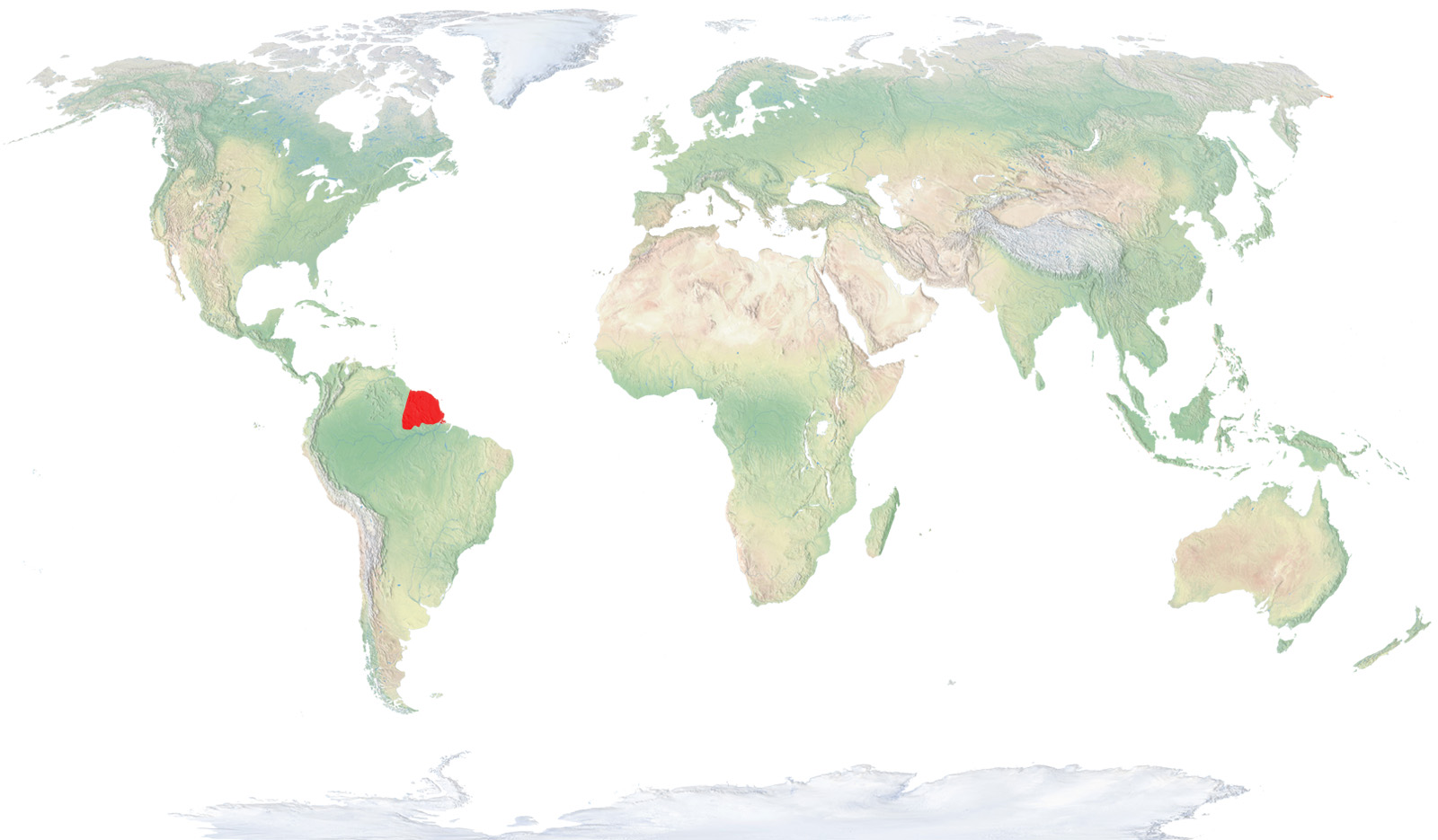

Moustached tamarins are inhabitants of tropical rainforests in Brazil, Bolivia and Peru.[4] They live in arid, upland forests in the Amazonian lowland, mostly occupying higher tree branches. The home range of moustached tamarins is between 25 and 50 hectares.[3]

Ecology

Moustached tamarins are omnivorous, frugivorous and insectivorous. Their diet mainly consists of fruits, nectar, gum exudates, invertebrates and small vertebrates. Invertebrates include katydids, stick grasshoppers, and spiders.[4] Vertebrates include lizards and frogs. Gum feeding is seasonal, however it is a dietary staple during dry and early wet seasons when other resources are scarce. Exudates supplement nutrients and balance mineral intake; which prevent the species from experiencing a range of detrimental effects from a low-calcium and high-phosphorus insectivorous diet. They display a highly opportunistic foraging pattern, and the ratio and variety of their comestibles depend on the availability in their geographical location. Moustached tamarins select trees by the amount of nectar they yield, rather than proximity to their home range. This higher volume of nectar makes the chosen trees more reliable because it allows them to feed for longer periods. Their remarkable spatial memory allows them to quickly recall the location of fruiting trees. Spatial memory is vital because it aids in the exploitation of a widely scattered set of feeding sites and minimizes effort in foraging.[4]

The moustached tamarin monkey is a crucial seed disperser for many plant species as a result of their diverse diet. They spread the seeds of fruits they ingest, indirectly impacting forest regeneration and maintenance. They are opportunistic feeders, utilizing a wide range of plant resources, allowing them to disperse a variety of seed species, providing significant benefit to their ecosystem.[4]

Moustached tamarins are territorial, however, they sometimes join with groups of brown-mantled tamarins (Leontocebus fuscicollis) and Geoffroy's saddle-back tamarin (Leontocebus nigrifrons).[3] These species can cohabit because they have varying locomotor types, hunting techniques, support preference, food selection, and reside in different strata of their forest habitat.[4] The brown-mantled tamarin and the moustached tamarin do not compete for the same resources. Sharing territory with another species facilitates predator avoidance, increasing survival chances for both groups. Having more eyes and ears provides greater protection.

Moustached tamarins are arboreal, diurnal,[3] and precocial.[citation needed] Tamarins walk and run on all fours, similar to squirrels and use their claws for stability. The moustached tamarin monkey exercises three types of locomotion. Symmetrical quadrupedalism is the most frequently used locomotion type, followed by asymmetric quadrupedalism, and leaping.[4] The kind of leap depends on the layer of the forest they occupy. In the lower canopy “trunk-to-trunk” leaps are performed.[3] These are jumps that are short and quick, only reaching a length of 1 to 2 meters.[3] While standing on a medium or large-sized trunk, they propel themselves into the air and land on their front limbs on another trunk. They perform “bounding” leaps which allow them to cross between discontinuous trees, extending their legs farther out, reaching up to 2 meters.[3] In the high canopy, they perform “acrobatic” leaps. These are longer leaps, reaching 5 meters or more, used to travel between treetops.[3] While in the air, they use their tail to decelerate their body before landing on the crown of a nearby tree.

Moustached tamarin monkeys select densely foliated areas for resting and sleeping to best camouflage themselves because their small size makes them an easy target. Their main tactic is to avoid predation by attracting as little attention as possible. Their predators include eagles and other birds of prey, snakes, tayras, jaguarundis, ocelots and other wild cats.[4]

Social grooming can be used to develop bonds. The moustached tamarins use their claws to detangle and comb one another's hair and remove parasites and dirt with their teeth and tongue.[3] Social grooming is not equally exercised by members and the amount of grooming services given and received depends on the social position of the individual.

Scent marking is used to identify territory boundaries and to communicate with others.[3] Females practice scent marking more frequently than males because it is also used in mate selection.[3] The three types of scent marking are circumanal marking, suprapubic marking and sternal marking.[5] Circumanal marking is the most commonly used type of scent marking.

Visual communication includes facial expressions, gestures, tonguing, and head-flicking. Tonguing is when a moustached tamarin moves its tongue across its lips. Head-flicking is when a moustached tamarin rapidly moves its head in an upward motion. Tonguing and head-flicking often co-occur and are used to communicate recognition, curiosity or anger.[citation needed]

Group sizes are usually 4-8 individuals, excluding infants, and each group usually contains 1 or 2 adult females.[3] However, groups have been observed to reach up to 15 individuals and solitary individuals have been encountered. Routinely, groups of moustached tamarins leave early in the morning to forage for food. They do not feed simultaneously. One of the adults positions themselves near the feeding site and scans the surroundings for predators to protect the group during mealtimes. They then retire at night in highly foliated areas to protect themselves from predators during slumber.[3]

There is often strife between neighboring groups of moustached tamarins due to limited food resources, especially near large feeding trees.[3] Vocal battles can arise, with long calls that consist of short syllables at a high frequency.[6] This type of conflict occurs between groups that are 25 meters or more apart.[6] Fights can be more aggressive however, often including alarm calls, visual contact, scent marking and a series of chases and retreats.[6] Adult males attack, inducing combative and loud vocalizations, while subadults chase one another.[3] Subsequently, there is a period of calm, and both groups forage for food and subadults examine the opposing group for mating opportunities.[3] The frequency of aggressive encounters increases during the breeding season and the majority of copulations occur during or directly after an aggressive encounter.[6]

Vocalizations allow moustached tamarins to distinguish between individuals, organize group movements, and ensure all members are accounted for. If individuals become separated, individuals of the same group will produce 2 to 3 second long vocalizations to indicate their location.[4] These calls consist of repeated short, frequency-modulated syllables ranging from 8 to 12 kilohertz.[4] In the morning, moustached tamarins make calls to each other to coordinate movement for the day towards specific foraging sites. Young tamarins also make vocalizations while they run and chase each other during play.

The reproduction season of the moustached tamarin monkey is November to March, during which the oldest female reproduces.[4] Females go into oestrus for about 17 days.[3] Their gestation period is about 145 days, after which females give birth.[4] Other members of the group help to take care of the infants, allowing the female to give birth more than once a year. The eldest female frequently bears twins because they ovulate multiple ova during each reproductive cycle.[3] The twins can be up to a quarter of the mother's size at birth. Females reach reproductive maturity at about 480 days, and males at 540 days.[4] Both sexes migrate to a different group in adulthood to avoid the risk of inbreeding.[3] Moustached tamarins practice a variety of mating systems: polyandry, polygyny or polygynandry.[3] The mothers often receive help from up to 4 or 5 other members of the group. In polyandrous groups, the alpha male tolerates the presence of other males who can provide infant-care.[3] Not having enough helpers can sometimes lead to infanticide by the mother.[3]

The population trend for the moustached tamarin monkey is decreasing; however, the IUCN red list categorizes the moustache tamarin as least concerned.[7] They have demonstrated an ability to adapt to disturbed habitats and proximity to human settlements. They can acclimate well to changes in environmental conditions and their ecosystem. Habitat destruction remains an inevitable threat to their population as for all species living in the Amazonian rainforest. However, their ability to adapt gives hope that this factor will not severely affect their population numbers.

Moustached tamarin monkeys are economically significant because they are used extensively in biomedical research, like other tamarin species. They have been used in the development of the hepatitis A vaccine.[citation needed]

Range of the Mustached Tamarin

Range of the emperor tamarin