The

fossa (

or

;

[3] Malagasy

[ˈfusə̥];

Cryptoprocta ferox) is a

cat-like, carnivorous

mammal endemic to

Madagascar. It is a member of the

Eupleridae, a

family of

carnivorans closely related to the

mongoose family (Herpestidae). Its

classification has been controversial because its physical traits resemble those of

cats, yet other traits suggest a close relationship with

viverrids (most

civets

and their relatives). Its classification, along with that of the other

Malagasy carnivores, influenced hypotheses about how many times

mammalian carnivores have colonized Madagascar. With genetic studies

demonstrating that the fossa and all other Malagasy carnivores are most

closely related to each other (forming a

clade,

recognized as the family Eupleridae), carnivorans are now thought to

have colonized the island once around 18 to 20 million years ago.

The fossa is the largest mammalian

carnivore on the island of Madagascar and has been compared to a small

cougar.

Adults have a head-body length of 70–80 cm (28–31 in) and weigh between

5.5 and 8.6 kg (12 and 19 lb), with the males larger than the females.

It has semi-retractable claws (meaning it can extend but not retract its

claws fully) and flexible ankles that allow it to climb up and down

trees head-first, and also support jumping from tree to tree. The fossa

is unique within its family for

the shape of its genitalia, which share traits with

those of cats and

hyenas.

The species is widespread, although

population densities

are usually low. It is found solely in forested habitat, and actively

hunts both by day and night. Over 50% of its diet consists of

lemurs, the endemic

primates found on the island;

tenrecs,

rodents,

lizards, birds, and other animals are also documented as prey. Mating

usually occurs in trees on horizontal limbs and can last for several

hours. Litters range from one to six pups, which are born blind and

toothless (

altricial). Infants wean after 4.5 months and are independent after a year.

Sexual maturity occurs around three to four years of age, and life expectancy in captivity is 20 years. The fossa is listed as "

Vulnerable" by the

International Union for Conservation of Nature. It is generally feared by the Malagasy people and is often protected by their

fady (taboo). The greatest threat to the species is

habitat destruction.

Etymology

The

generic name Cryptoprocta refers to how the animal's

anus is hidden by its anal pouch, from the

Ancient Greek words

crypto- "hidden", and

procta "anus".

[4] The

species name ferox is the

Latin adjective "fierce" or "wild". Its

common name is spelled fossa in English or

fosa in

Malagasy, the

Austronesian language from which it was taken,

[4][6] but some authors have adopted the Malagasy spelling in English. The word is similar to

posa (meaning "cat") in the

Iban language (another Austronesian language) from

Borneo, and both terms may derive from

trade languages from the 1600s. However, an alternative

etymology suggests a link to another word that comes from

Malay:

pusa refers to the

Malayan weasel (

Mustela nudipes). The Malay word

pusa could have become

posa for cats in Borneo, while in Madagascar the word could have become

fosa to refer to the fossa.

[6]

Taxonomy

The fossa was formally described by

Edward Turner Bennett on the basis of a specimen from Madagascar sent by

Charles Telfair in 1833.

[8] The common name is the same as the generic name of the

Malagasy civet (

Fossa fossana), but they are different species. Because of shared physical traits with

civets,

mongooses, and cats (

Felidae), its

classification has been controversial. Bennett originally placed the fossa as a type of civet in the family

Viverridae, a classification that long remained popular among taxonomists. Its compact

braincase, large

eye sockets, retractable claws, and specialized carnivorous

dentition have also led some taxonomists to associate it with the felids. In 1939,

William King Gregory and Milo Hellman placed the fossa in its own subfamily within Felidae, the Cryptoproctinae.

George Gaylord Simpson placed it back in Viverridae in 1945, still within its own subfamily, yet conceded it had many cat-like characteristics.

[4]

The fossa has a cat-like appearance, resembling a small

cougar.

[4]

In 1993, Géraldine Veron and François Catzeflis published a

DNA hybridization study suggesting that the fossa was more closely related to mongooses (family

Herpestidae) than to cats or civets. However, in 1995, Veron's

morphological study once again grouped it with Felidae. In 2003,

molecular phylogenetic studies using

nuclear and

mitochondrial genes by

Anne Yoder

and colleagues showed that all native Malagasy carnivorans share a

common ancestry that excludes other carnivores (meaning they form a

clade, making them

monophyletic) and are most closely related to Asian and African Herpestidae.

[11][12][13] To reflect these relationships, all Malagasy carnivorans are now placed in a single family,

Eupleridae.

[1] Within Eupleridae, the fossa is placed in the subfamily

Euplerinae along with the

falanouc (

Eupleres goudoti) and Malagasy civet, but its exact relationships are poorly resolved.

[1][11][13]

An extinct relative of the fossa was described in 1902 from

subfossil remains and recognized as a separate species,

Cryptoprocta spelea,

in 1935. This species was larger than the living fossa (with a body

mass estimate roughly twice as great), but otherwise similar.

[4][14] Across Madagascar, people distinguish two kinds of fossa—a large

fosa mainty ("black fossa") and the smaller

fosa mena

("reddish fossa")—and a white form has been reported in the southwest.

It is unclear whether this is purely folklore or individual

variation—related to sex, age or instances of

melanism and

leucism—or whether there is indeed more than one species of living fossa.

[4][14]

Description

The fossa appears as a diminutive form of a large felid, such as a cougar, but with a slender body and muscular limbs, and a tail nearly as long as the rest of the body. It has a

mongoose-like head, relatively longer than that of a cat, although with a muzzle that is broad and short, and with large but rounded ears.

[4]

It has medium brown eyes set relatively wide apart with pupils that

contract to slits. Like many carnivorans that hunt at night, its

eyes reflect light; the reflected light is orange in hue. Its head-body length is 70–80 cm (28–31 in) and its tail is 65–70 cm (26–28 in) long. There is some

sexual dimorphism, with adult males (weighing 6.2–8.6 kg or 14–19 lb) being larger than females (5.5–6.8 kg or 12–15 lb). Smaller individuals are typically found north and east on Madagascar, while larger ones to the south and west.

[4]

Unusually large individuals weighing up to 20 kg (44 lb) have been

reported, but there is some doubt as to the reliability of the

measurements. The fossa can smell, hear, and see well. It is a robust animal and illnesses are rare in captive fossas.

[16]

Cranium (dorsal, ventral, and lateral views) and mandible (lateral and dorsal views)

Both males and females have short, straight fur that is relatively

dense and without spots or patterns. Both sexes are generally a

reddish-brown dorsally and colored a dirty cream ventrally. When in

rut, they may have an orange coloration to their

abdomen from a reddish substance secreted by a chest

gland

secretions, but this has not been consistently observed by all

researchers. The tail tends to be lighter in coloration than the sides.

Juveniles are either gray or nearly white.

[4]

Several of the animal's physical features are adaptions to climbing through trees. It uses its tail to assist balance and has semi-retractable claws that it uses to climb trees in its search for prey. It has

semiplantigrade feet,

[4] switching between a plantigrade-like gait (when

arboreal) and a

digitigrade-like one (when

terrestrial).

[17] The soles of its paws are nearly bare and covered with strong pads.

[4]

The fossa has very flexible ankles that allow it to readily grasp tree

trunks so as to climb up or down trees head first or to leap to another

tree. Captive juveniles have been known to swing upside down by their hindfeet from knotted ropes.

The fossa has several

scent glands, although the glands are less developed in females. Like herpestids it has a

perianal skin gland inside an

anal sac

which surrounds the anus like a pocket. The pocket opens to the

exterior with a horizontal slit below the tail. Other glands are located

near the penis or vagina, with the

penile glands emitting a strong odor. Like the herpestids, it has no

prescrotal glands.

[4]

External genitalia

External genitalia of Cryptoprocta ferox

One of the more peculiar physical features of this species is its

external genitalia. The male fossa has an unusually long penis and

baculum (penis bone),

[18] reaching to between his forelegs when erect, with an average thickness of 20 mm (0.79 in). The

glans extends about halfway down the

shaft and

is spiny except at the tip. In comparison, the

glans of felids is short and spiny, while that of viverrids is smooth and long.

[4] The female fossa exhibits transient

masculization, starting at about 1–2 years of age, developing an enlarged, spiny

clitoris that resembles a male's penis. The enlarged clitoris is supported by an

os clitoridis,

[19] which decreases in size as the animal grows.

[17] The females do not have a pseudo-scrotum, but they do secrete an orange substance that colors their underparts, much like the secretions of males. Hormone levels (

testosterone,

androstenedione,

dihydrotestosterone)

do not seem to play a part in this transient masculization, as those

levels are the same in masculinized juveniles and nonmasculinized

adults. It is speculated that the transient masculization either reduces

sexual harassment of juvenile females by adult males, or reduces

aggression from

territorial females. While females of other mammal species (such as the

spotted hyena) have a

pseudo-penis,

[21] no other is known to diminish in size as the animal grows.

Comparison with related carnivorans

Overall,

the fossa has features in common with three different carnivoran

families, leading researchers to place it and other members of

Eupleridae alternatively in Herpestidae, Viverridae, and Felidae. Felid

features are primarily those associated with eating and

digestion, including tooth shape and

facial portions of the skull, the tongue, and the

digestive tract,

[4] typical of its exclusively carnivorous diet. The remainder of the skull most closely resembles skulls of genus

Viverra, while the general body structure is most similar to that of various members of Herpestidae. The permanent dentition is

3.1.3-4.13.1.3-4.1 (three

incisors, one

canine, three or four

premolars, and one

molar on each side of both the upper and lower jaws), with the

deciduous formula being similar but lacking the fourth premolar and the molar. The fossa has a large, prominent

rhinarium

similar to that of viverrids, but has comparatively larger, round ears,

almost as large as those of a similarly sized felid. Its facial

vibrissae (whiskers) are long, with the longest being longer than its head. Like some mongoose genera, particularly

Galidia (which is now in the fossa's own family, Eupleridae) and

Herpestes (of Herpestidae), it has

carpal

vibrissae as well. Its claws are retractile, but unlike those of

Felidae species, they are not hidden in skin sheaths. It has three pairs

of nipples (one inguinal, one ventral, and one pectoral).

[4]

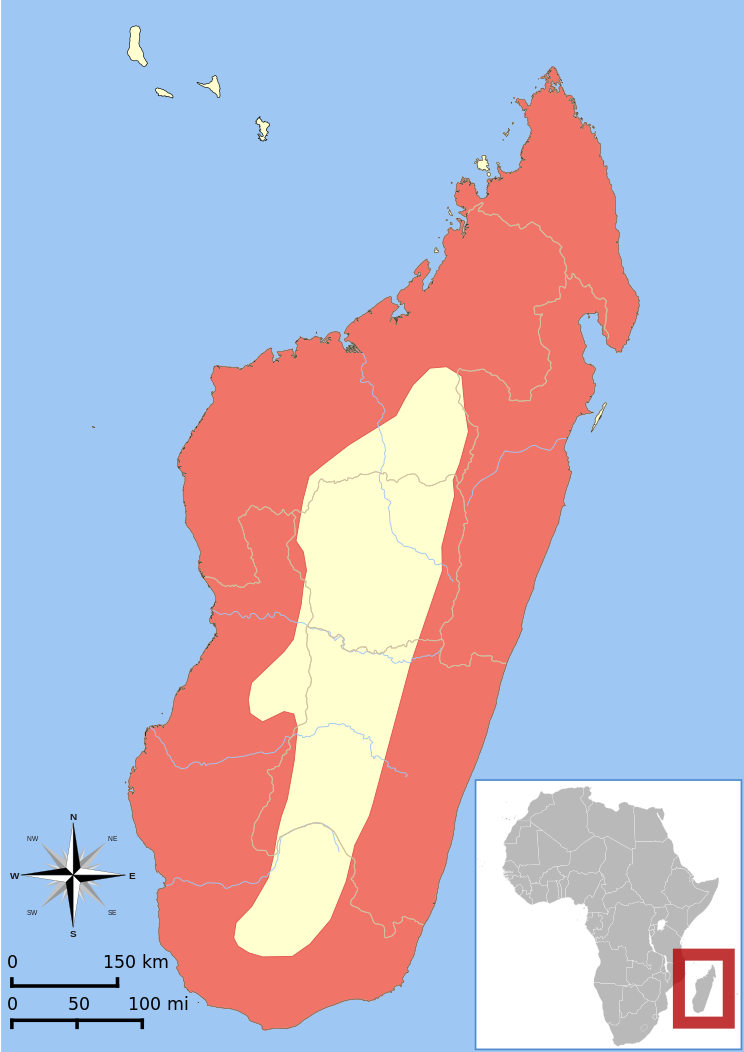

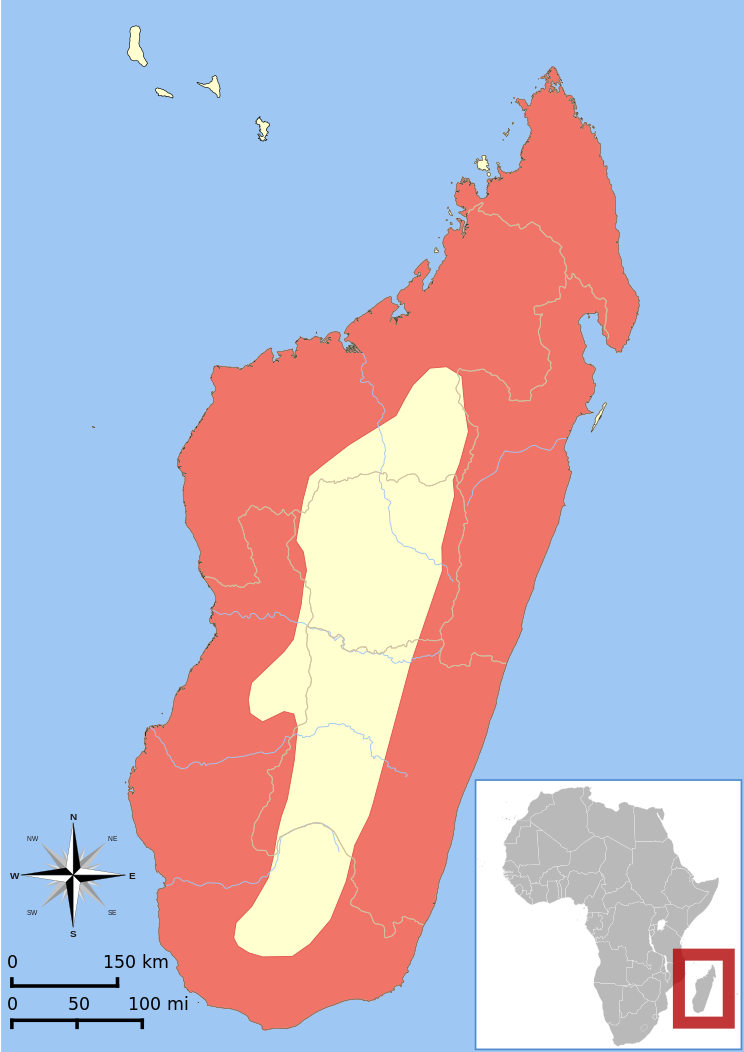

Habitat and distribution

The

fossa has the most widespread geographical range of the Malagasy

carnivores, and is generally found in low numbers throughout the island

in remaining tracts of forest, preferring pristine undisturbed forest

habitat. It is also encountered in some degraded forests, but in lower

numbers. Although the fossa is found in all known forest habitats

throughout Madagascar, including the western, dry

deciduous forests, the eastern

rainforests, and the southern

spiny forests, it is seen more frequently in humid than in dry forests. This may be because the reduced

canopy in dry forests provides less shade, and also because the fossa seems to travel more easily in humid forests.

It is absent from areas with the heaviest habitat disturbance and, like

most of Madagascar's fauna, from the central high plateau of the

country.

The fossa has been found across several different elevational

gradients in undisturbed portions of protected areas throughout

Madagascar. In the Réserve Naturelle Intégrale d'Andringitra, evidence

of the fossa has been reported at four different sites ranging from 810

to 1,625 m (2,657 to 5,331 ft).

[23] Its highest known occurrence was reported at 2,000 m (6,600 ft); its presence high on the

Andringitra Massif was subsequently confirmed in 1996.

[23]

Similarly, evidence has been reported of the fossa at the elevational

extremes of 440 m (1,440 ft) and 1,875 m (6,152 ft) in the

Andohahela National Park.

[25]

The presence of the fossa at these locations indicates its ability to

adapt to various elevations, consistent with its reported distribution

in all Madagascar forest types.

Behavior

The fossa is active during both the day and the night and is considered

cathemeral; activity peaks may occur early in the morning, late in the afternoon, and late in the night. The animal generally does not reuse sleeping sites, but females with young do return to the same den. The home ranges of male fossas in

Kirindy Forest are up to 26 km

2 (10 sq mi) large, compared to 13 km

2

(5.0 sq mi) for females. These ranges overlap—by about 30 percent

according to data from the eastern forests—but females usually have

separated ranges. Home ranges grow during the dry season, perhaps

because less food and water is available. In general,

radio-collared fossas travel between 2 and 5 kilometres (1.2 and 3.1 mi) per day,

[26] although in one reported case a fossa was observed moving a straight-line distance of 7 km (4.3 mi) in 16 hours. The animal's population density appears to be low: in

Kirindy Forest, where it is thought to be common, its density has been estimated at one animal per 4 km

2 (1.5 sq mi) in 1998. Another study in the same forest between 1994 and 1996 using the

mark and recapture method indicated a population density of one animal per 3.8 km

2 (1.5 sq mi) and one adult per 5.6 km

2 (2.2 sq mi).

[27]

Except for mothers with young and occasional observations of pairs of

males, animals are usually found alone, so that the species is

considered solitary.

[4][27]

A 2009 publication, however, reported a detailed observation of

cooperative hunting, wherein three male fossas hunted a 3 kg (6.6 lb)

sifaka (

Propithecus verreauxi)

for 45 minutes, and subsequently shared the prey. This behavior may be a

vestige of cooperative hunting that would have been required to take

down larger

recently extinct lemurs.

[28]

Fossas communicate using sounds, scents, and visual signals. Vocalizations include purring, a threatening call,

[4] and a call of fear, consisting of "repeated loud, coarse inhalations and gasps of breath".

A long, high yelp may function to attract other fossas. Females mew

during mating and males produce a sigh when they have found a female.

[4] Throughout the year, animals produce long-lasting

scent marks on rocks, trees, and the ground using glands in the anal region and on the chest.

[4] They also communicate using face and body expression, but the significance of these signals is uncertain.

[4]

The animal is aggressive only during mating, and males in particular

fight boldly. After a short fight, the loser flees and is followed by

the winner for a short distance.

[4]

In captivity, fossas are usually not aggressive and sometimes even

allow themselves to be stroked by a zookeeper, but adult males in

particular may try to bite.

[16]

Diet

The fossa is a

carnivore

that hunts small to medium-sized animals. One of eight carnivorous

species endemic to Madagascar, the fossa is the island's largest

surviving endemic terrestrial mammal and the only predator capable of

preying upon adults of all extant

lemur species,

[26][29] the largest of which can weigh as much as 90 percent of the weight of the average fossa.

[29] Although it is the predominant predator of lemurs,

[29][30]

reports of its dietary habits demonstrate a wide variety of prey

selectivity and specialization depending on habitat and season; diet

does not vary by sex. While the fossa is thought to be a lemur

specialist in

Ranomafana National Park,

[31] its diet is more variable in other rain forest habitats.

The diet of the fossa in the wild has been studied by analyzing their distinctive

scats, which resemble gray cylinders with twisted ends and measure 10–14 cm (3.9–5.5 in) long by 1.5–2.5 cm (0.6–1.0 in) thick.

[32]

Scat collected and analyzed from both Andohahela and Andringitra

contained lemur matter and rodents. Eastern populations in Andringitra

incorporate the widest recorded variety of prey, including both

vertebrates and

invertebrates. Vertebrates consumed ranged from reptiles to a wide variety of birds, including both

understory and ground birds, and mammals, including

insectivores,

rodents, and lemurs. Invertebrates eaten by the fossa in the high mountain zone of Andringitra include insects and crabs.

[23][25] One study found that vertebrates comprised 94% of the diet of fossas, with lemurs comprising over 50%, followed by

tenrecs

(9%), lizards (9%), and birds (2%). Seeds, which comprised 5% of the

diet, may have been in the stomachs of the lemurs eaten, or may have

been consumed with fruit taken for water, as seeds were more common in

the stomach in the dry season. The average prey size varies

geographically; it is only 40 grams (1.4 oz) in the high mountains of

Andringitra, in contrast to 480 grams (17 oz) in humid forests and over

1,000 grams (35 oz) in dry deciduous forests.

In a study of fossa diet in the dry deciduous forest of western

Madagascar, more than 90% of prey items were vertebrates, and more than

50% were lemurs. The primary diet consisted of approximately six lemur

species and two or three spiny tenrec species, along with snakes and

small mammals.

[32] Generally, the fossa preys upon larger lemurs and rodents in preference to smaller ones.

[33]

Prey is obtained by hunting either on the ground or in the trees.

During the non-breeding season the fossa hunts individually, but during

the breeding season hunting parties may be seen, and these may be pairs

or later on mothers and young. One member of the group scales a tree and

chases the lemurs from tree to tree, forcing them down to the ground

where the other is easily able to capture them. The fossa is known to eviscerate its larger lemur prey, a trait that, along with its distinct scat, helps identify its kills.

[29] Long-term observations of the fossa's predation patterns on rainforest

sifakas suggest that the fossa hunts in a subsection of their range until prey density is decreased, then moves on.

[34]

The fossa has been reported to prey on domestic animals, such as goats

and small calves, and especially chickens. Food taken in captivity

includes amphibians, birds, insects, reptiles, and small- to

medium-sized mammals.

[4]

This wide variety of prey items taken in various rainforest habitats is similar to the varied dietary composition noted

[23][25]

occurring in the dry forests of western Madagascar, as well. As the

largest endemic predator on Madagascar, this dietary flexibility

combined with a flexible activity pattern

[26] has allowed it to exploit a wide variety of niches available throughout the island,

[23][25] making it a potential

keystone species for the Madagascar ecosystems.

Breeding

Fossa illustration circa 1927

Most of the details of reproduction in wild populations are from the

western dry deciduous forests; determining whether or not certain of

these details are applicable to eastern populations will require further

field research. Mating typically occurs during September and October,

[4] although there are reports of its occurring as late as December, and can be highly conspicuous. In captivity in the

Northern Hemisphere, fossas instead mate in the northern spring, from March to July.

[16] Intromission

usually occurs in trees on horizontal limbs about 20 m (66 ft) off the

ground. Frequently the same tree is used year after year, with

remarkable precision as to the date the season commences. Trees are

often near a water source, and have limbs strong enough and wide enough

to support the mating pair, about 20 cm (7.9 in) wide. Some mating has

been reported on the ground as well.

As many as eight males will be at a mating site, staying in close

vicinity to the receptive female. The female seems to choose the male

she mates with, and the males compete for the attention of the female

with a significant amount of

vocalization

and antagonistic interactions. The female may choose to mate with

several of the males, and her choice of mate does not seem to have any

correlation to the physical appearance of the males.

To stimulate the male to mount her, she gives a series of mewling

vocalizations. The male mounts from behind, resting his body on her

slightly off-center,

a position requiring delicate balance; if the female were to stand, the

male would have significant difficulty continuing. He places his paws

on her shoulders or grasps her around the waist and often licks her neck. Mating may last for nearly three hours.

This unusually lengthy mating is due to the physical nature of the

male's erect penis, which has backwards-pointing spines along most of

its length. Fossa mating includes a

copulatory tie, which may be enforced by the male's spiny penis. The tie is difficult to break if the mating session is interrupted.

Copulation with a single male may be repeated several times, with a

total mating time of up to fourteen hours, while the male may remain

with the female for up to an hour after the mating. A single female may

occupy the tree for up to a week, mating with multiple males over that

time. Also, other females may take her place, mating with some of the

same males as well as others.

This mating strategy, whereby the females monopolize a site and

maximize the available number of mates, seems to be unique among

carnivores. Recent research suggests that this system helps the fossa

overcome factors which would normally impede mate-finding, such as low

population density and lack of den use.

[35]

The birthing of the litter of one to six

[17] (typically two to four)

[4]

takes place in a concealed location, such as an underground den, a

termite mound, a rock crevice, or in the hollow of a large tree (particularly those of the

Commiphora genus). Contrary to older research, litters are of mixed sexes.

[4] Young are born in December or January, making the

gestation period 90 days,

[4] with the late mating reports indicating a gestational period of about six to seven weeks. The newborns are blind and toothless and weigh no more than 100 g (3.5 oz).

[4] The fur is thin and has been described as gray-brown

[16] or nearly white. After about two weeks the cubs' eyes open,

[4][16] they become more active, and their fur darkens to a pearl gray. The cubs do not take solid food until three months old, and do not leave the den until they are 4.5 months old; they are weaned shortly after that.

[4] After the first year, the juveniles are independent of their mother. Permanent teeth appear at 18 to 20 months.

[4] Physical maturity is reached by about two years of age, but

sexual maturity is not attained for another year or two,

[4]

and the young may stay with their mother until they are fully mature.

Lifespan in captivity is up to or past 20 years of age, possibly due to

the slow juvenile development.

[17]

Human interactions

The fossa has been assessed as "

Vulnerable" by the

IUCN Red List

since 2008, as its population size has probably declined by at least

30 percent between 1987 and 2008; previous assessments have included "

Endangered" (2000) and "Insufficiently Known" (1988, 1990, 1994).

[2]

The species is dependent on forest and thus threatened by the

widespread destruction of Madagascar's native forest but is also able to

persist in disturbed areas. A suite of

microsatellite markers (short segments of DNA that have a repeated

sequence) have been developed to help aid in studies of genetic health and

population dynamics of both captive and wild fossas.

[36] Several

pathogens have been isolated from the fossa, some of which, such as

anthrax and

canine distemper, are thought to have been transmitted by feral dogs or cats.

Toxoplasma gondii was reported in a captive fossa in 2013.

[37]

Although the species is widely distributed, it is locally rare in all

regions, making fossas particularly vulnerable to extinction. The

effects of

habitat fragmentation

increase the risk. For its size, the fossa has a lower than predicted

population density, which is further threatened by Madagascar's rapidly

disappearing forests and dwindling lemur populations, which make up a

high proportion of its diet. The loss of the fossa, either locally or

completely, could significantly impact ecosystem dynamics, possibly

leading to over-grazing by some of its prey species. The total

population of the fossa living within protected areas is estimated at

less than 2,500 adults, but this may be an overestimate. Only two

protected areas are thought to contain 500 or more adult fossas:

Masoala National Park and

Midongy-Sud National Park, although these are also thought to be overestimated. Too little population information has been collected for a formal

population viability analysis, but estimates suggest that none of the protected areas support a

viable population.

If this is correct, the extinction of the fossa may take as much as

100 years to occur as the species gradually declines. In order for the

species to survive, it is estimated that at least 555 km

2 (214 sq mi) is needed to maintain smaller, short-term viable populations, and at least 2,000 km

2 (770 sq mi) for populations of 500 adults.

[27]

Taboo, known in Madagascar as

fady, offers protection for the fossa and other carnivores.

[39] In the Marolambo District (part of the

Atsinanana region in

Toamasina Province),

the fossa has traditionally been hated and feared as a dangerous

animal. It has been described as "greedy and aggressive", known for

taking fowl and piglets, and believed to "take little children who walk

alone into the forest". Some do not eat it for fear that it will

transfer its undesirable qualities to anyone who consumes it. However, the animal is also taken for

bushmeat;

a study published in 2009 reported that 57 percent of villages (8 of 14

sampled) in the Makira forest consume fossa meat. The animals were

typically hunted using slingshots, with dogs, or most commonly, by

placing

snare traps on animal paths.

[40] Near

Ranomafana National Park, the fossa, along with several of its smaller cousins and the introduced

small Indian civet (

Viverricula indica),

are known to "scavenge on the bodies of ancestors", which are buried in

shallow graves in the forest. For this reason, eating these animals is

strictly prohibited by

fady. However, if they wander into

villages in search of domestic fowl, they may be killed or trapped.

Small carnivore traps have been observed near chicken runs in the

village of Vohiparara.

[39]

Fossas are occasionally held in captivity in

zoos. They first bred in captivity in 1974 in the zoo of

Montpellier, France. The next year, at a time when there were only eight fossas in the world's zoos, the

Duisburg Zoo

in Germany acquired one; this zoo later started a successful breeding

program, and most zoo fossas now descend from the Duisburg population.

Research on the Duisburg fossas has provided much data about their

biology.

[16]

The fossa was depicted as an antagonist in the DreamWorks 2005 animated film

Madagascar, accurately shown as the lemurs' most feared predator.

[41]

References

Conservation

Conservation