The white-bellied sea eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster), also known as the white-breasted sea eagle, is a large diurnal bird of prey in the family Accipitridae. Originally described by Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1788, it is closely related to Sanford's sea eagle of the Solomon Islands, and the two are considered a superspecies. A distinctive bird, the adult white-bellied sea eagle has a white head, breast, under-wing coverts and tail. The upper parts are grey and the black under-wing flight feathers contrast with the white coverts. The tail is short and wedge-shaped as in all Haliaeetus species. Like many raptors, the female is slightly larger than the male, and can measure up to 90 cm (35 in) long with a wingspan of up to 2.2 m (7.2 ft), and weigh 4.5 kg (9.9 lb). Immature birds have brown plumage, which is gradually replaced by white until the age of five or six years. The call is a loud goose-like honking.

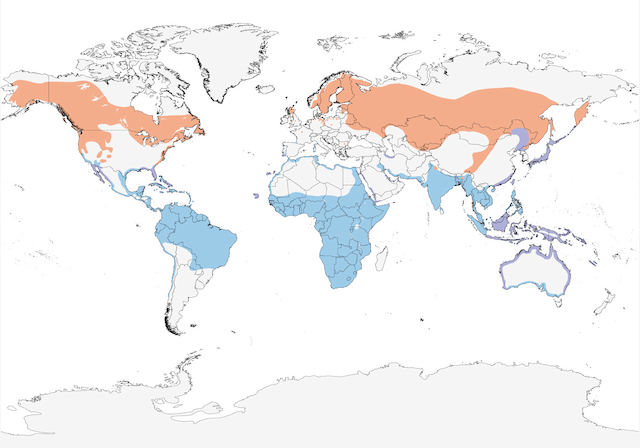

Resident from India and Sri Lanka through Southeast Asia to Australia on coasts and major waterways, the white-bellied sea eagle breeds and hunts near water, and fish form around half of its diet. Opportunistic, it consumes carrion and a wide variety of animals. Although rated as Least Concern globally, it has declined in parts of southeast Asia such as Thailand, and southeastern Australia. It is ranked as Threatened in Victoria and Vulnerable in South Australia and Tasmania. Human disturbance to its habitat is the main threat, both from direct human activity near nests which impacts on breeding success, and from removal of suitable trees for nesting. The white-bellied sea eagle is revered by indigenous people in many parts of Australia, and is the subject of various folk tales throughout its range.

Taxonomy

The white-bellied sea eagle was first described by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1788, although John Latham had made notes on the species in 1781, from a specimen obtained in February 1780 at Princes Island off the westernmost cape of Java during Captain Cook's last voyage.[2] Its specific name is derived from the Ancient Greek leuko- 'white',[3] and gaster 'belly'.[4] Its closest relative is the little-known Sanford's sea eagle of the Solomon Islands. These form a superspecies, and as is usual in other sea eagle superspecies, one (the white-bellied sea eagle) has a white head, as opposed to the other species' dark head. The bill and eyes are dark, and the talons are dark yellow as in all Southern Hemisphere sea eagles. Both these species have at least some dark colouration in their tails, though this may not always be clearly visible in the white-bellied sea eagle. The nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome b gene of the two sea eagles were among those analysed in a 1996 study. Although they differ greatly in appearance and ecology, their genetic divergence of 0.3% indicates that the ancestors of the two forms might have diverged as recently as 150,000 years ago. The study authors conclude that although the genetic divergence is more consistent with subspecies, the distinctness in appearance and behaviour warrants the two being retained as separate species.[5] Mitochondrial sequence of the cytochrome b locus differs very slightly from that of Sanford's sea eagle suggesting a relatively recent divergence after New Guinea-based white-bellied sea eagles colonised the Solomon Islands.[6][7]

The white-bellied sea eagle's affinities beyond the Sanford's sea eagle are a little less clear; molecular data indicate that it is one of four species of tropical sea eagle (along with the African fish eagle and the Madagascar fish eagle), while allozyme data indicate it might have a closer relationship with the sea eagles of the northern hemisphere.[6][8] A further molecular study published in 2005 showed the white-bellied and Sanford's sea eagles to be basal to the four fish eagles (the two mentioned above plus the two hitherto untested species of the genus Ichthyophaga).[9]

As well as white-bellied sea eagle and white-breasted sea eagle, other recorded names include white-bellied fish-hawk, white-eagle,[10] and grey-backed sea eagle.[11]

Description

The white-bellied sea eagle has a white head, rump and underparts, and dark or slate-grey back and wings. In flight, the black flight feathers on the wings are easily seen when the bird is viewed from below. The large, hooked bill is a leaden blue-grey with a darker tip, and the irides are dark brown. The cere is also lead grey. The legs and feet are yellow or grey, with long black talons (claws). Unlike those of eagles of the genus Aquila, the legs are not feathered. The sexes are similar. Males are 66–80 cm (26–31 in) long and weigh 1.8–3 kg (4.0–6.6 lb). Females are slightly larger, at 80–90 cm (31–35 in) and 2.5–4.5 kg (5.5–9.9 lb). The wingspan ranges from 1.78 to 2.2 m (5.8 to 7.2 ft).[12][13][14] A 2004 study on 37 birds from Australia and Papua New Guinea (3 °S to 50 °S) found that birds could be sexed reliably on size, and that birds from latitudes further south were larger than those from the north.[15] There is no seasonal variation in plumage.[16] The moulting pattern of the white-bellied sea eagle is poorly known. It appears to take longer than a year to complete, and can be interrupted and later resumed from the point of interruption.[17]

The wings are modified when gliding so that they rise from the body at an angle, but are closer to horizontal further along the wingspan. In silhouette, the comparatively long neck, head and beak stick out from the front almost as far as the tail does behind. For active flight, the white-bellied sea eagle alternates strong deep wing-beats with short periods of gliding.[16]

A young white-bellied sea eagle in its first year is predominantly brown,[12] with pale cream-streaked plumage on their head, neck, nape and rump areas.[16] The plumage becomes more infiltrated with white until it acquires the complete adult plumage by the fourth or fifth year.[12] The species breeds from around six years of age onwards.[18] The lifespan is thought to be around 30 years.[19]

The loud goose-like honking call is a familiar sound, particularly during the breeding season; pairs often honk in unison,[20] and often carry on for some time when perched. The male's call is higher-pitched and more rapid than that of the female. Australian naturalist David Fleay observed that the call is among the loudest and furthest-carrying of all Australian bird calls, in stark contrast to the relatively quiet calls of the wedge-tailed eagle.[21]

Adult white-bellied sea eagles are unmistakable and unlikely to be confused with any other bird. Immature birds can be confused with wedge-tailed eagles. However, the plumage of the latter is darker, the tail longer, and the legs feathered. They might also be confused with the black-breasted buzzard (Hamirostra melanosternon), but this species is much smaller, has white patches on the wings, and has a more undulating flight.[22] In India, the Egyptian vulture has white plumage, but is smaller and has a whiter back and wings. The white tail of the white-bellied sea eagle in flight distinguishes it from other species of large eagles.[23] In the Philippines, it can be confused with the Philippine eagle, which can be distinguished by its crest; immature white-bellied sea eagles resemble immature grey-headed fish eagles, but can be identified by their more wholly dark brown underparts and flight feathers, and wedge-shaped tail.[24]

Distribution and habitat

The white-bellied sea eagle is found regularly from Mumbai (sometimes north to Gujarat,[25] and in the past in the Lakshadweep Islands) eastwards in India,[26][27] Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka in southern Asia, through all of coastal Southeast Asia including Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Indochina,[20] the main and offshore islands of the Philippines,[24] and southern China including Hong Kong,[20] Hainan and Fuzhou,[11] eastwards through New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago,[28] and Australia. In the northern Solomons it is restricted to Nissan Island,[29] and replaced elsewhere by Sanford's sea eagle.[28] In Victoria, where it is otherwise scarce, it is locally more common at Corner Inlet and Gippsland Lakes.[30] Similarly in South Australia, it is most abundant along the north coast of Kangaroo Island.[31] The range extends to the islands of Bass Strait and Tasmania, and it is thought able to move between the islands and the mainland.[32] There is one unconfirmed record from Lord Howe Island and several from New Zealand.[33]

They are a common sight in coastal areas, but may also be seen well inland (It is reportedly seen at the Panna Tiger Reserve in central India, nearly 1,000 km (621 mi) away from the sea shore)[34][35] The white-bellied sea eagle is generally sedentary and territorial, although it may travel long distances. They have been reported travelling upriver to hunt for flying foxes (Pteropus). Populations in inland Australia move around as inland bodies of water appear and then dry up.[33] In one instance, a pair came to breed at Lake Albacutya in northwestern Victoria after the lake had been empty for 30 years.[36] The species is easily disturbed by humans, especially when nesting, and may desert nesting sites as a result. It is found in greater numbers in areas with little or no human impact or interference.[37]

Behaviour

The white-bellied sea eagle is generally territorial; some birds form permanent pairs that inhabit territories throughout the year, while others are nomadic. The species is monogamous, with pairs remaining together until one bird dies, after which the surviving bird quickly seeks a new mate. This can lead to some nest sites being continuously occupied for many years (one site in Mallacoota was occupied for over fifty years).[18] Immature birds are generally dispersive, with many moving over 50 km (31 mi) away from the area they were raised. One juvenile raised in Cowell, South Australia was reported 3,000 km (1,900 mi) away at Fraser Island in Queensland.[38] A study of the species in Jervis Bay showed increases in the numbers of immature and subadult birds in autumn, although it was unclear whether these were locally fledged or (as was considered more likely) an influx of young birds born and raised elsewhere in Australia.[39] Birds are often seen perched high in a tree, or soaring over waterways and adjacent land. They are most commonly encountered singly or in pairs. Small groups of white-bellied sea eagles sometimes gather if there is a plentiful source of food such as a carcass or fish offal on a ship.[18] Much of the white-bellied sea eagle's behaviour, particularly breeding, remains poorly known.[40]

Breeding

The breeding season varies according to location—it has been recorded in the dry season in the Trans-Fly region and Central Province of Papua New Guinea,[28] and from June to August in Australia.[41] A pair of white-bellied sea eagles performs skilful displays of flying before copulation: diving, gliding and chasing each other while calling loudly. They may mirror each other, flying 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft) apart and copying each other swooping and swerving. A talon-grappling display has been recorded where the pair will fly high before one flips upside down and tries to grapple the other's talons with its own. If successful, the two then plunge cartwheeling before separating as they approach the ground.[42][12] This behaviour has also been recorded as an aggressive display against a wedge-tailed eagle.[43]

The white-bellied sea eagle usually chooses tall trees or man-made pylons to nest in.[22] Often, locations are sought where there is a tall dead tree or high branch with good visibility which can be used as a perch to survey the surrounding area,[22] which is generally a low-lying locale near water with some forest cover.[44] The perch becomes covered in faeces and pellets and animal remains litter the immediate surrounding area.[18] The nest is a large deep bowl constructed of sticks and branches, and lined with such materials as grass or seaweed. Yearly renovations result in nests getting gradually bigger. Nests are generally sited in the forks of large trees overlooking bodies of water.[45] Old nests of wedge-tailed eagles or whistling kites have been renovated and used.[30] Cliffs are also suitable nesting sites, and on islands nests are sometimes built directly on the ground. A breeding pair, with the male being more active, spends three to six weeks building or renovating the nest before laying eggs.[40] Normally a clutch of two dull, white, oval eggs are laid. Measuring 73×55 mm,[41] they are incubated over six weeks before hatching. The young are semi-altricial, and covered in white down when they emerge from the egg. Initially, the male brings food and the female feeds the chicks, but both parents feed the chicks as they grow larger. Although two eggs are laid, it is unusual for two young to be reared successfully to fledging (leaving the nest). One egg may be infertile, or the second chick may die in the nest.[46] If the first clutch is lost, the parents may attempt a second brood.[47] Nestlings have been recorded fledging when 70 to 80 days old, and remaining around the parents' territory for up to six months or until the following breeding season.[40]

Feeding

The white-bellied sea eagle is an opportunistic carnivore and consumes a wide variety of animal prey, including carrion.[38] It often catches a fish by flying low over the water and grasping it in its talons.[12] It prepares for the strike by holding its feet far forward (almost under its chin) and then strikes backwards while simultaneously beating its wings to lift upwards. Generally only one foot is used to seize prey.[38] The white-bellied sea eagle may also dive at a 45-degree angle from its perch and briefly submerge to catch fish near the water surface.[38] While hunting over water on sunny days, it often flies directly into the sun or at right angles to it, seemingly to avoid casting shadows over the water and hence alerting potential prey.[47]

The white-bellied sea eagle hunts mainly aquatic animals, such as fish, turtles and sea snakes,[48] but it takes birds, such as little penguins, Eurasian coots and shearwaters, and mammals (including flying foxes) as well.[12][49] In the Bismarck Archipelago it has been reported feeding on two species of possum, the northern common cuscus and common spotted cuscus.[50] It is a skilled hunter, and will attack prey up to the size of a swan. They also feed on carrion such as dead sheep, birds and fish found along the waterline, as well as raiding fishing nets and following cane harvesters.[12][38]

They harass smaller raptors such as swamp harriers, whistling kites, brahminy kites and ospreys, forcing them to drop any food that they are carrying.[12][38] Other birds victimised include silver and Pacific gulls, cormorants and Australasian gannets. There is one record of a white-bellied sea eagle seizing a gannet when unsuccessful in obtaining its prey. They may even steal food from their own species, including their mates. The white-bellied sea eagle attacks these birds by striking them with outstretched talons from above or by flying upside down underneath the smaller predator and snatching the prey, all the while screeching shrilly.[38] Southern fur seals have also been targeted for their fish.[51]

White-bellied sea eagles feed alone, in pairs, or in family groups. A pair may cooperate to hunt.[38] Prey can be eaten while the bird is flying or when it lands on a raised platform such as its nest. The white-bellied sea eagle skins the victim as it eats it.[38] It is exceptionally efficient at digesting its food, and disgorges only tiny pellets of fragmented bone, fur and feathers.[21]

A 2006 study of inland bodies of water around Canberra where wedge-tailed eagles and white-bellied sea eagles share territories showed little overlap in the range of prey taken. Wedge-tailed eagles took rabbits, various macropods, terrestrial birds such as cockatoos and parrots, and various passerines including magpies and starlings. White-bellied sea eagles caught fish, water-dwelling reptiles such as the eastern long-necked turtle and Australian water dragon, and waterbirds such as ducks, grebes and coots. Both species preyed on the maned duck. Rabbits constituted only a small fraction of the white-bellied sea eagle's diet. Despite nesting near each other, the two species seldom interacted, as the wedge-tailed eagles hunted away from water and the white-bellied sea eagles foraged along the lake shores.[52] However, conflict with wedge-tailed eagles over nesting sites in remnant trees has been recorded in Tasmania.[39]

Conservation status

The white-bellied sea eagle is listed as being of Least Concern by the IUCN.[1] There are an estimated 10 thousand to 100 thousand individuals, although there seems to be a decline in numbers. They have become rare in Thailand and some other parts of southeast Asia.[11] They are relatively abundant in Hong Kong, where the population increased from 39 to 57 birds between 2002 and 2009.[53] A field study on Kangaroo Island in South Australia showed that nesting pairs in areas of high human disturbance (as defined by clearing of landscape and high human activity) had lower breeding success rates.[54] In the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia, nests have been vacated as human activities have encroached on the eagles' territories.[55] Elsewhere, the clearing of trees suitable for nesting has seen it largely disappear locally, such as the removal of stands of Casuarina equisetifolia in Visakhapatnam district in Andhra Pradesh in India.[56] In India, nest densities of about one per 4.32 km of coastline have been noted in Sindhudurg and one per 3.57 km (45 nests along 161 km) in Ratnagiri district of Maharashtra.[57][58] They also nest on Netrani Island, where about a 100 birds were noted in 1875 (then known as Pigeon Island) by Allan Octavian Hume who noted that this was perhaps the largest breeding colony of the species.[59] In 2000, the disturbance to the island from torpedo-firing exercises conducted by the Indian navy was noted as a threat.[60] Nearly 100 nests have been noted in 2004 on this island.[61]

DDT was a widely used pesticide in agriculture that was found to have significant adverse effects on wildlife, particularly egg thinning and subsequent breakage in birds of prey. A review of DDT's impact on Australian raptors between 1947 and 1993 found that the average egg-shell thickness had decreased by 6%. This average level of thinning was not thought likely to result in significantly more breakage overall, however individual clutches that had been even thinner might have broken. The white-bellied sea eagle was one of the more affected species, probably due to its feeding in areas heavily treated with pesticide such as swamps. DDT use peaked in 1973, but was no longer approved after 1987 and its use had effectively ceased by 1989.[62]

Australia

The white-bellied sea eagle is listed under the marine and migratory categories which give it protected status under Australia's federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. As a mainly coastal species, it is vulnerable to habitat destruction in Australia's increasingly populated and urbanised coastal areas, particularly in the south and east of the country, where it appears to have declined in numbers. However, there may have been an increase in population inland, secondary to the creation of reservoirs, dams and weirs, and the spread of the introduced common carp (Cyprinus carpio). However, it is rare along the Murray River where it was once common.[37] It is also listed as Threatened under Victoria's Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (1988), with possibly fewer than 100 breeding pairs remaining in the state.[30] On the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria, the white-bellied sea eagle is listed as vulnerable.[63]

There are fewer than 1000 adult birds in Tasmania, where the species is listed as Vulnerable under Schedule 3.1 of the Tasmanian Threatened Species Protection Act 1995. In Tasmania it is threatened by nest disturbance, loss of suitable nesting habitat, shooting, poisoning, trapping, and collision with power lines and wind turbines, as well as entanglement and environmental pollution. Estuaries are a favoured habitat, and these are often subject to environmental disturbance.[64] white-bellied sea eagles have been observed to increase their hunting ranges to include salmon fish farms, but the effect of this on breeding success is unknown.[65]

Cultural significance

The white-bellied sea eagle was important to different tribes of indigenous people across Australia. The guardian animal of the Wreck Bay aboriginal community, it is also the official emblem of the Booderee National Park and Botanic Gardens in the Jervis Bay Territory. The community considered localities around Booderee National Park to be connected with it.[10] A local Sydney name was gulbi, and the bird was the totem of Colebee, the late 18th century indigenous leader of the Cadigal people.[66] The white-bellied sea eagle is important to the Mak Mak people of the floodplains to the southwest of Darwin in the northern Territory, who recognised its connection with "good country". It is their totem and integrally connected to their land.[67] The term Mak Mak is their name for both the species and themselves.[68] The Umbrawarra Gorge Nature Park was a Dreaming site of the bird, in this area known as Kuna-ngarrk-ngarrk.[69] It was similarly symbolic to the Tasmanian indigenous people—Nairanaa was one name used there.[70]

Known as Manulab to the people of Nissan Island, the white-bellied sea eagle is considered special and killing it is forbidden. Its calls at night are said to foretell danger, and seeing a group of calling eagles flying overhead is a sign that someone has died.[71] Local Malay folk tales tell of the white-bellied sea eagle screaming to warn the shellfish of the turning of tides, and a local name burung hamba siput translates as "slave of the shellfish".[72] Called Kaulo in the recently extinct Aka-Bo language, the white-bellied sea eagle was held to be the ancestor of all birds in one Andaman Islands folk tale.[73] On the Maharashtra coast, their name is kakan and its call is said to indicate the presence of fish in the sea. They sometimes nest on coconut trees. Owners of the trees destroy the nest to avoid attacks when harvesting the coconuts.[57]

The white-bellied sea eagle is featured on the $10,000 Singapore note,[72] which was introduced into circulation on 1 February 1980.[74] It is the emblem of the Malaysian state of Selangor.[72] Malay magnate Loke Wan Tho had a 40-metre-high (130 ft) tower built for the sole purpose of observing a white-bellied sea eagle nest in the palace gardens of Istana Bukit Serene in Johor Bahru.[75] Taken in February 1949, the resulting photographs appeared in The Illustrated London News in 1954.[76] The bird is the emblem of the Manly-Warringah Sea Eagles rugby league team,[10] chosen at the club's inception in 1947.[77] From 2010, a nesting pair of white-bellied sea eagles have had their attempts at raising chicks filmed live on "EagleCam", with footage on display at the nearby Birds Australia Discovery Centre in Sydney Olympic Park, New South Wales. After raising one brood, however, their nest collapsed in February 2011.[78] The story attracted statewide attention.[79]

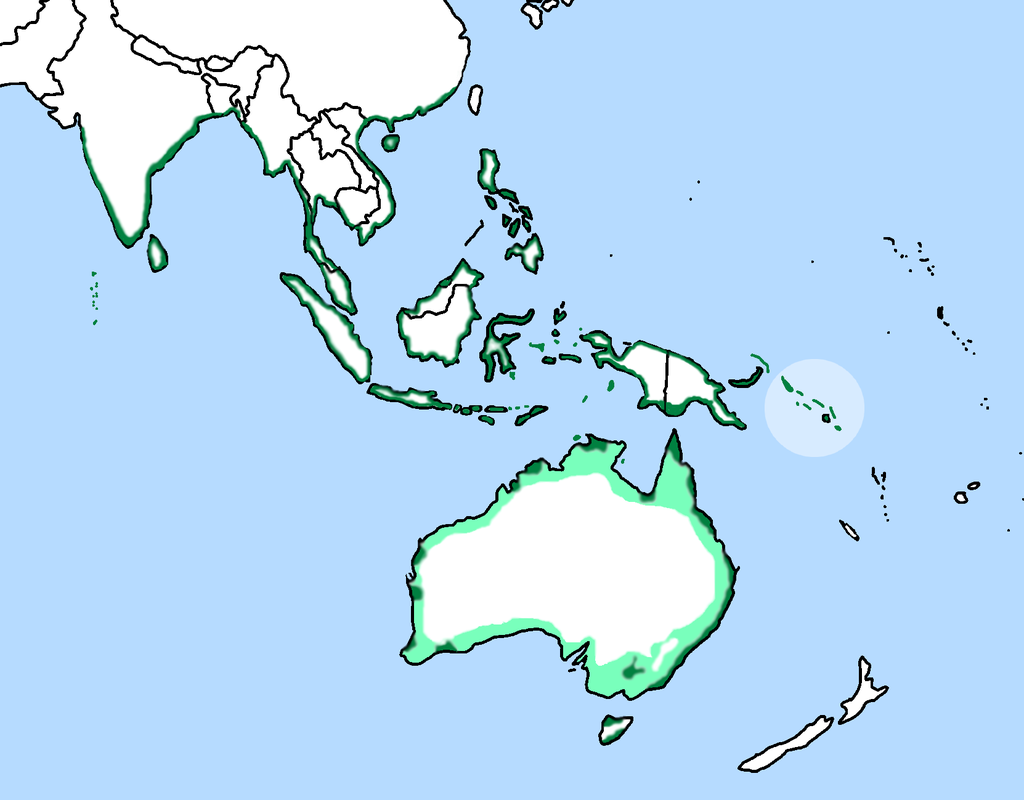

Haliaeetus leucogaster

Range of both this species and Sanford's sea eagle shown in green, but the latter demarcated within a paler blue circle