/GettyImages-528162130-53d0c5076eb14915ade61b5d3021294f.jpg)

The capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) is a giant cavy rodent native to South America. It is the largest living rodent.[2] Also called capivara (in Brazil), capiguara (in Bolivia), chigüire, chigüiro, or fercho (in Colombia and Venezuela), carpincho (in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay) and ronsoco (in Peru), it is a member of the genus Hydrochoerus, of which the only other extant member is the lesser capybara (Hydrochoerus isthmius). Its close relatives include guinea pigs and rock cavies, and it is more distantly related to the agouti, the chinchilla, and the coypu. The capybara inhabits savannas

and dense forests and lives near bodies of water. It is a highly social

species and can be found in groups as large as 100 individuals, but

usually lives in groups of 10–20 individuals. The capybara is not a

threatened species and it is hunted for its meat and hide and also for grease from its thick fatty skin.[3]

Etymology

Its common name is derived from Tupi ka'apiûara, a complex agglutination of kaá (leaf) + píi (slender) + ú (eat) + ara (a suffix for agent nouns), meaning "one who eats slender leaves", or "grass-eater".[4]

The scientific name, both hydrochoerus and hydrochaeris, comes from Greek ὕδρω (hydro "water") and χοῖρος (choiros "pig, hog").[5][6]

Classification and phylogeny

The capybara and the lesser capybara belong to the subfamily Hydrochoerinae along with the rock cavies. The living capybaras and their extinct relatives were previously classified in their own family Hydrochoeridae.[7] Since 2002, molecular phylogenetic studies have recognized a close relationship between Hydrochoerus and Kerodon, the rock cavies,[8] supporting placement of both genera in a subfamily of Caviidae.[5]

Paleontological classifications previously used Hydrochoeridae

for all capybaras, while using Hydrochoerinae for the living genus and

its closest fossil relatives, such as Neochoerus,[9][10] but more recently have adopted the classification of Hydrochoerinae within Caviidae.[11]

The taxonomy of fossil hydrochoerines is also in a state of flux. In

recent years, the diversity of fossil hydrochoerines has been

substantially reduced.[9][10] This is largely due to the recognition that capybara molar teeth show strong variation in shape over the life of an individual.[9]

In one instance, material once referred to four genera and seven

species on the basis of differences in molar shape is now thought to

represent differently aged individuals of a single species, Cardiatherium paranense.[9]

Among fossil species, the name "capybara" can refer to the many species

of Hydrochoerinae that are more closely related to the modern Hydrochoerus than to the "cardiomyine" rodents like Cardiomys.[11] The fossil genera Cardiatherium, Phugatherium, Hydrochoeropsis, and Neochoerus are all capybaras under that concept.

Description

The capybara has a heavy, barrel-shaped

body and short head, with reddish-brown fur on the upper part of its

body that turns yellowish-brown underneath. Its sweat glands can be

found in the surface of the hairy portions of its skin, an unusual trait

among rodents.[7] The animal lacks down hair, and its guard hair differs little from over hair.[12]

Adult capybaras grow to 106 to 134 cm (3.48 to 4.40 ft) in length, stand 50 to 62 cm (20 to 24 in) tall at the withers, and typically weigh 35 to 66 kg (77 to 146 lb), with an average in the Venezuelan llanos of 48.9 kg (108 lb).[13][14][15]

Females are slightly heavier than males. The top recorded weights are

91 kg (201 lb) for a wild female from Brazil and 73.5 kg (162 lb) for a

wild male from Uruguay.[7][16] Also, an 81 kg individual was reported in São Paulo in 2001 or 2002.[17] The dental formula is 1.0.1.31.0.1.3.[7] Capybaras have slightly webbed feet and vestigial tails.[7]

Their hind legs are slightly longer than their forelegs; they have

three toes on their rear feet and four toes on their front feet.[18] Their muzzles are blunt, with nostrils, and the eyes and ears are near the top of their heads.

Its karyotype has 2n = 66 and FN = 102.[5][7]

Ecology

A family of Capybara swimming

Capybaras are semiaquatic mammals[15] found throughout almost all countries of South America except Chile.[19] They live in densely forested areas near bodies of water, such as lakes, rivers, swamps, ponds, and marshes,[14] as well as flooded savannah and along rivers in the tropical rainforest. They are superb swimmers and can hold their breath underwater for up to five minutes at a time.[20] Capybara have flourished in cattle ranches.[7] They roam in home ranges averaging 10 hectares (25 acres) in high-density populations.[7]

Many escapees from captivity can also be found in similar watery habitats around the world. A breeding population now occurs in Trinidad. Sightings are fairly common in Florida, although a breeding population has not yet been confirmed.[21] These escaped populations occur in areas where prehistoric capybaras inhabited; late Pleistocene capybaras inhabited Florida[22] and Hydrochoerus gaylordi in Grenada. In 2011, one specimen was spotted on the Central Coast of California.[23]

Diet and predation

Capybaras are herbivores, grazing mainly on grasses and aquatic plants,[14][24] as well as fruit and tree bark.[15] They are very selective feeders[25]

and feed on the leaves of one species and disregard other species

surrounding it. They eat a greater variety of plants during the dry

season, as fewer plants are available. While they eat grass during the

wet season, they have to switch to more abundant reeds during the dry

season.[26] Plants that capybaras eat during the summer lose their nutritional value in the winter, so they are not consumed at that time.[25] The capybara's jaw hinge is not perpendicular, so they chew food by grinding back-and-forth rather than side-to-side.[27] Capybaras are autocoprophagous, meaning they eat their own feces as a source of bacterial gut flora, to help digest the cellulose

in the grass that forms their normal diet, and to extract the maximum

protein and vitamins from their food. They may also regurgitate food to

masticate again, similar to cud-chewing by cattle.[28]

As is the case with other rodents, the front teeth of capybaras grow

continually to compensate for the constant wear from eating grasses;[19] their cheek teeth also grow continuously.[27]

Like its relative the guinea pig, the capybara does not have the capacity to synthesize vitamin C, and capybaras not supplemented with vitamin C in captivity have been reported to develop gum disease as a sign of scurvy.[29]

They can have a lifespan of 8–10 years,[30] but tend to live less than four years in the wild due to predation from jaguars, pumas, ocelots, eagles, and caimans.[19] The capybara is also the preferred prey of the green anaconda.[31]

Social organization

Capybaras have a scent gland on their noses, called a morrillo

Capybaras are known to be gregarious.

While they sometimes live solitarily, they are more commonly found in

groups of around 10–20 individuals, with two to four adult males, four

to seven adult females, and the remainder juveniles.[32] Capybara groups can consist of as many as 50 or 100 individuals during the dry season[28][33] when the animals gather around available water sources. Males establish social bonds, dominance, or general group consensus.[clarification needed][33] They can make dog-like barks[28] when threatened or when females are herding young.[34]

Capybaras have two types of scent glands; a morrillo, located on the snout, and anal glands.[35]

Both sexes have these glands, but males have much larger morrillos and

use their anal glands more frequently. The anal glands of males are also

lined with detachable hairs. A crystalline form of scent secretion is

coated on these hairs and is released when in contact with objects such

as plants. These hairs have a longer-lasting scent mark and are tasted

by other capybaras. Capybaras scent-mark by rubbing their morrillos on

objects, or by walking over scrub and marking it with their anal glands.

Capybaras can spread their scent further by urinating; however, females

usually mark without urinating and scent-mark less frequently than

males overall. Females mark more often during the wet season when they

are in estrus. In addition to objects, males also scent-mark females.[35]

Reproduction

Mother with typical litter of about four pups.

When in estrus, the female's scent changes subtly and nearby males begin pursuit.[36] In addition, a female alerts males she is in estrus by whistling through her nose.[28]

During mating, the female has the advantage and mating choice.

Capybaras mate only in water, and if a female does not want to mate with

a certain male, she either submerges or leaves the water.[28][33] Dominant males are highly protective of the females, but they usually cannot prevent some of the subordinates from copulating.[36]

The larger the group, the harder it is for the male to watch all the

females. Dominant males secure significantly more matings than each

subordinate, but subordinate males, as a class, are responsible for more

matings than each dominant male.[36] The lifespan of the capybara's sperm is longer than that of other rodents.[37]

Capybara gestation is 130–150 days, and produces a litter of four capybaras young on average, but may produce between one and eight in a single litter.[7]

Birth is on land and the female rejoins the group within a few hours of

delivering the newborn capybaras, which join the group as soon as they

are mobile. Within a week, the young can eat grass, but continue to

suckle—from any female in the group—until weaned around 16 weeks. The

young form a group within the main group.[19] Alloparenting has been observed in this species.[33] Breeding peaks between April and May in Venezuela and between October and November in Mato Grosso, Brazil.[7]

Activities

Though quite agile

on land, capybaras are equally at home in the water. They are excellent

swimmers, and can remain completely submerged for up to five minutes,[14] an ability they use to evade predators. Capybaras can sleep in water, keeping only their noses out of the water. As temperatures increase during the day, they wallow in water and then graze during the late afternoon and early evening.[7] They also spend time wallowing in mud.[18] They rest around midnight and then continue to graze before dawn.

Conservation and human interaction

Capybaras are not considered a threatened species;[1] their population is stable throughout most of their South American range, though in some areas hunting has reduced their numbers.[14][19]

Capybaras are hunted for their meat and pelts in some areas,[38] and otherwise killed by humans who see their grazing as competition for livestock. In some areas, they are farmed, which has the effect of ensuring the wetland habitats are protected. Their survival is aided by their ability to breed rapidly.[19]

Capybaras have adapted well to urbanization in South America. They can be found in many areas in zoos and parks,[27] and may live for 12 years in captivity, more than double their wild lifespan.[19]

Capybaras are docile and usually allow humans to pet and hand-feed

them, but physical contact is normally discouraged, as their ticks can be vectors to Rocky Mountain spotted fever.[39]

The European Association of Zoos and Aquaria asked Drusillas Park in Alfriston, Sussex, England to keep the studbook

for capybaras, to monitor captive populations in Europe. The studbook

includes information about all births, deaths and movements of

capybaras, as well as how they are related.[40]

Capybaras are farmed for meat and skins in South America.[41] The meat is considered unsuitable to eat in some areas, while in other areas it is considered an important source of protein.[7] In parts of South America, especially in Venezuela, capybara meat is popular during Lent and Holy Week as the Catholic Church previously issued special dispensation to allow it to be eaten while other meats are generally forbidden.[42]

López de Ceballos (1974)[43] as cited in Herrera & Barreto (2013)[44] p. 307 states that after several attempts a 1784 Papal bull was obtained that allowed the consumption of capybara during Lent.

There is widespread perception in Venezuela that consumption of capybaras is exclusive to rural people.[45]

Although it is illegal in some states,[46] capybaras are occasionally kept as pets in the United States.[47]

The image of a capybara features on the 2-peso coin of Uruguay.[48]

In Japan, following the lead of Izu Shaboten Park in 1982,[49] multiple establishments or zoos in Japan that raise capybaras have adopted the practice of having them relax in onsen during the winter. They are seen as an attraction by Japanese people.[49] Capybaras became big in Japan due to the popular cartoon character Kapibara-san.[50]

Brazilian Lyme-like borreliosis likely involves capybaras as reservoirs and Amblyomma and Rhipicephalus ticks as vectors.[51]

Capybaras in a bath at Izu Shaboten Park in Japan

Binomial name

Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris

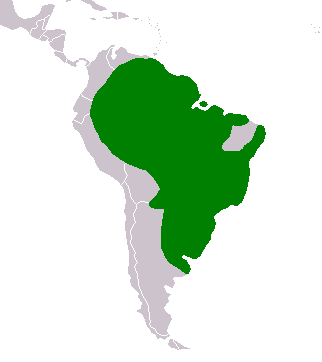

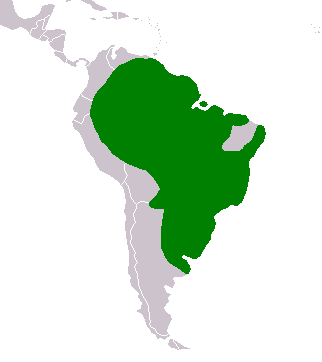

Native range

:strip_icc()/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_59edd422c0c84a879bd37670ae4f538a/internal_photos/bs/2019/Q/2/vMy5mAQ5eNqfJlAGLiow/1-caluromys-lanatus-hudson-garcia-uhe-salto-caxias-pr.jpg)

Water opossum range

Water opossum range

/GettyImages-528162130-53d0c5076eb14915ade61b5d3021294f.jpg)