The

common blackbird (

Turdus merula) is a

species of

true thrush. It is also called

Eurasian blackbird (especially in North America, to distinguish it from the unrelated

New World blackbirds),

[2] or simply

blackbird where this does not lead to confusion with a

similar-looking local species. It breeds in Europe, Asia, and North Africa, and has been

introduced to Australia and New Zealand.

[3] It has a number of

subspecies across its large range; a few of the Asian subspecies are sometimes considered to be full species. Depending on

latitude, the common blackbird may be

resident, partially

migratory, or fully migratory.

The adult male of the

nominate subspecies, which is found throughout most of Europe, is all black except for a yellow eye-ring and

bill and has a rich, melodious

song; the adult female and juvenile have mainly dark brown

plumage. This species breeds in woods and gardens, building a neat, mud-lined, cup-shaped nest. It is

omnivorous, eating a wide range of

insects,

earthworms,

berries, and

fruits.

Both sexes are

territorial

on the breeding grounds, with distinctive threat displays, but are more

gregarious during migration and in wintering areas. Pairs stay in their

territory throughout the year where the climate is sufficiently

temperate.

This common and conspicuous species has given rise to a number of

literary and cultural references, frequently related to its song.

Male T. m. merula

Taxonomy and systematics

Female

T. m. mauretanicus

The common blackbird was described by

Linnaeus in the

10th edition of his Systema Naturae in 1758 as

Turdus merula (characterised as

T. ater, rostro palpebrisque fulvis).

[4] The binomial name derives from two

Latin words,

turdus, "thrush", and

merula, "blackbird", the latter giving rise to its French name,

merle,

[5] and its

Scots name,

merl.

[6]

About 65 species of medium to large thrushes are in the genus

Turdus, characterised by rounded heads, longish, pointed wings, and usually melodious songs. Although two European thrushes, the

song thrush and

mistle thrush, are early offshoots from the Eurasian lineage of

Turdus thrushes after they spread north from Africa, the blackbird is descended from ancestors that had colonised the

Caribbean islands from Africa and subsequently reached Europe from there.

[7] It is close in evolutionary terms to the

island thrush (

T. poliocephalus) of Southeast Asia and islands in the southwest Pacific, which probably diverged from

T. merula stock fairly recently.

[8]

It may not immediately be clear why the name "blackbird", first

recorded in 1486, was applied to this species, but not to one of the

various other common black English birds, such as the

carrion crow,

raven,

rook, or

jackdaw. However, in

Old English, and in

modern English

up to about the 18th century, "bird" was used only for smaller or young

birds, and larger ones such as crows were called "fowl". At that time,

the blackbird was therefore the only widespread and conspicuous "black

bird" in the British Isles.

[9] Until about the 17th century, another name for the species was

ouzel,

ousel or

wosel (from

Old English osle, cf. German

Amsel). Another variant occurs in Act 3 of

Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, where

Bottom

refers to "The Woosell cocke, so blacke of hew, With Orenge-tawny

bill". The ouzel usage survived later in poetry, and still occurs as the

name of the closely related

ring ouzel (

Turdus torquatus), and in water ouzel, an alternative name for the unrelated but superficially similar

white-throated dipper (

Cinclus cinclus).

[10]

Juvenile T. m. merula in England

A

leucistic adult male in England with much white in the plumage

Two related Asian

Turdus thrushes, the

white-collared blackbird (

T. albocinctus) and the

grey-winged blackbird (

T. boulboul), are also named blackbirds,

[8] and the

Somali thrush (

T. (olivaceus) ludoviciae) is alternatively known as the Somali blackbird.

[11]

The

icterid

family of the New World is sometimes called the blackbird family

because of some species' superficial resemblance to the common blackbird

and other Old World thrushes, but they are not evolutionarily close,

being related to the

New World warblers and

tanagers.

[12] The term is often limited to smaller species with mostly or entirely black plumage, at least in the breeding male, notably the

cowbirds,

[13] the

grackles,

[14] and for around 20 species with "blackbird" in the name, such as the

red-winged blackbird and the

melodious blackbird.

[12]

Subspecies

As

would be expected for a widespread passerine bird species, several

geographical subspecies are recognised. The treatment of subspecies in

this article follows Clement

et al. (2000).

[8]

Female of subspecies merula

- T. m. merula, the nominate subspecies, breeds commonly throughout much of Europe from Iceland, the Faroes and the British Isles east to the Ural Mountains and north to about 70 N, where it is fairly scarce. A small population breeds in the Nile Valley. Birds from the north of the range winter throughout Europe and around the Mediterranean including Cyprus and North Africa. The introduced birds in Australia and New Zealand are of the nominate race.[8]

- T. m. azorensis is a small race which breeds in the Azores. The male is darker and glossier than merula.[15]

- T. m. cabrerae, named for Ángel Cabrera, Spanish zoologist, resembles azorensis and breeds in Madeira and the western Canary Islands.[15]

- T. m. mauretanicus, another small dark species with a glossy black male plumage, breeds in central and northern Morocco, coastal Algeria and northern Tunisia.[15]

First-summer male, probably subspecies aterrimus

- T m. aterrimus breeds in Hungary, south and east to southern Greece, Crete northern Turkey and northern Iran. It winters in southern Turkey, northern Egypt, Iraq and southern Iran. It is smaller than merula with a duller male and paler female plumage.[15]

- T. m. syriacus breeds on the Mediterranean coast of southern Turkey south to Jordan, Israel and the northern Sinai. It is mostly resident, but part of the population moves south west or west to winter in the Jordan Valley and in the Nile Delta of northern Egypt south to about Cairo. Both sexes of this subspecies are darker and greyer than the equivalent merula plumages.[8]

- T. m. intermedius is an Asiatic race breeding from Central Russia to Tajikistan,

western and north east Afghanistan, and eastern China. Many birds are

resident but some are altitudinal migrants and occur in southern

Afghanistan and southern Iraq in winter.[8] This is a large subspecies, with a sooty-black male and a blackish-brown female.[16]

The Asian subspecies, the relatively large

intermedius also differs in structure and voice, and may represent a distinct species.

[16] Alternatively, it has been suggested that they should be considered subspecies of

T. maximus,

[8] but they differ in structure, voice and the appearance of the eye-ring.

[16][17]

Similar species

In Europe, the common blackbird can be confused with the paler-winged first-winter

ring ouzel (

Turdus torquatus) or the superficially similar

European starling (

Sturnus vulgaris).

[18] A number of similar

Turdus thrushes exist far outside the range of the common blackbird, for example the South American

Chiguanco thrush (

Turdus chiguanco).

[19] The

Indian blackbird, the

Tibetan blackbird, and the

Chinese blackbird were formerly considered subspecies.

[20]

Description

The common blackbird of the

nominate subspecies

T. m. merula is 23.5 to 29 centimetres (9.25 to 11.4 in) in length, has a long tail, and weighs 80–125 grams (2.8 to 4.4

oz). The adult male has glossy black

plumage, blackish-brown legs, a yellow eye-ring and an orange-yellow

bill. The bill darkens somewhat in winter.

[18]

The adult female is sooty-brown with a dull yellowish-brownish bill, a

brownish-white throat and some weak mottling on the breast. The

juvenile

is similar to the female, but has pale spots on the upperparts, and the

very young juvenile also has a speckled breast. Young birds vary in the

shade of brown, with darker birds presumably males.

[18]

The first year male resembles the adult male, but has a dark bill and

weaker eye ring, and its folded wing is brown, rather than black like

the body plumage.

[8]

Distribution and habitat

The common blackbird breeds in temperate Eurasia, North Africa, the

Canary Islands, and South Asia. It has been introduced to Australia and New Zealand.

[8] Populations are

sedentary in the south and west of the range, although northern birds

migrate south as far as northern Africa and tropical Asia in winter.

[8] Urban males are more likely to

overwinter

in cooler climes than rural males, an adaptation made feasible by the

warmer microclimate and relatively abundant food that allow the birds to

establish territories and start reproducing earlier in the year.

[21] Recoveries of blackbirds ringed on the

Isle of May show that these birds commonly migrate from southern Norway ( or from as far north as

Trondheim)

to Scotland, and some onwards to Ireland. Scottish-ringed birds have

also been recovered in England, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, and Sweden

[22]. Female blackbirds in Scotland and the north of England migrate more (to Ireland) in winter than do the males

[23]

Common over most of its range in woodland, the common blackbird

has a preference for deciduous trees with dense undergrowth. However,

gardens provide the best breeding habitat with up to 7.3 pairs per

hectare (nearly three pairs per

acre), with woodland typically holding about a tenth of that density, and open and very built-up habitats even less.

[24] They are often replaced by the related

ring ouzel in areas of higher altitude.

[25] The common blackbird also lives in parks, gardens and hedgerows.

[26]

The common blackbird occurs up to 1000 metres (3300 ft) in

Europe, 2300 metres (7590 ft) in North Africa, and at 900–1820 metres

(3000–6000 ft) in peninsular India and Sri Lanka, but the large

Himalayan subspecies range much higher, with

T. m. maximus breeding at 3200–4800 metres (10560–16000 ft) and remaining above 2100 metres (6930 ft) even in winter.

[8]

This widespread species has occurred as a vagrant in many

locations in Eurasia outside its normal range, but records from North

America are normally considered to involve escapees, including, for

example, the 1971 bird in

Quebec.

[27] However, a 1994 record from

Bonavista, Newfoundland, has been accepted as a genuine wild bird,

[8] and the species is therefore on the

North American list.

[28]

Behaviour and ecology

Two chicks in their first hours as another egg begins to hatch

The male common blackbird defends its breeding territory, chasing

away other males or utilising a "bow and run" threat display. This

consists of a short run, the head first being raised and then bowed with

the tail dipped simultaneously. If a fight between male blackbirds does

occur, it is usually short and the intruder is soon chased away. The

female blackbird is also aggressive in the spring when it competes with

other females for a good nesting territory, and although fights are less

frequent, they tend to be more violent.

[24]

The

bill's

appearance is important in the interactions of the common blackbird.

The territory-holding male responds more aggressively towards models

with orange bills than to those with yellow bills, and reacts least to

the brown bill colour typical of the first-year male. The female is,

however, relatively indifferent to bill colour, but responds instead to

shinier bills.

[29]

As long as winter food is available, both the male and female

will remain in the territory throughout the year, although occupying

different areas. Migrants are more gregarious, travelling in small

flocks and feeding in loose groups in the wintering grounds. The flight

of migrating birds comprises bursts of rapid wing beats interspersed

with level or diving movement, and differs from both the normal fast

agile flight of this species and the more dipping action of larger

thrushes.

[15]

Breeding

The male common blackbird attracts the female with a courtship

display which consists of oblique runs combined with head-bowing

movements, an open beak, and a "strangled" low song. The female remains

motionless until she raises her head and tail to permit copulation.

[24] This species is monogamous, and the established pair will usually stay together as long as they both survive.

[15] Pair separation rates of up to 20% have been noted following poor breeding.

[30] Although the species is socially monogamous, there have been studies showing as much as 17% extra-pair paternity.

[31]

Nominate

T. merula may commence breeding in March, but

eastern and Indian races are a month or more later, and the introduced

New Zealand birds start nesting in August (late winter).

[8][25] The breeding pair prospect for a suitable nest site in a creeper or bush, favouring evergreen or thorny species such as

ivy,

holly,

hawthorn,

honeysuckle or

pyracantha.

[32] Sometimes the birds will nest in sheds or outbuildings where a ledge or cavity is used. The cup-shaped

nest

is made with grasses, leaves and other vegetation, bound together with

mud. It is built by the female alone. She lays three to five (usually

four) bluish-green

eggs marked with reddish-brown blotches,

[24] heaviest at the larger end;

[25] the eggs of nominate

T. merula are 2.9×2.1 centimetres (1.14×0.93 in) in size and weigh 7.2 grammes (0.25 oz), of which 6% is shell.

[33] Eggs of birds of the southern Indian races are paler than those from the northern subcontinent and Europe.

[8]

The female incubates for 12–14 days before the

altricial

chicks are hatched naked and blind. Fledging takes another 10–19

(average 13.6) days, with both parents feeding the young and removing

faecal sacs.

[15] The nest is often ill-concealed compared with those of other species, and many breeding attempts fail due to predation.

[34]

The young are fed by the parents for up to three weeks after leaving

the nest, and will follow the adults begging for food. If the female

starts another nest, the male alone will feed the fledged young.

[24]

Second broods are common, with the female reusing the same nest if the

brood was successful, and three broods may be raised in the south of the

common blackbird's range.

[8]

A common blackbird has an average

life expectancy of 2.4 years,

[35] and, based on data from

bird ringing, the oldest recorded age is 21 years and 10 months.

[36]

Songs and calls

In its native

Northern Hemisphere

range, the first-year male common blackbird of the nominate race may

start singing as early as late January in fine weather in order to

establish a territory, followed in late March by the adult male. The

male's song is a varied and melodious low-pitched fluted warble, given

from trees, rooftops or other elevated perches mainly in the period from

March to June, sometimes into the beginning of July. It has a number of

other calls, including an aggressive

seee, a

pook-pook-pook alarm for terrestrial predators like cats, and various

chink and

chook, chook vocalisations. The territorial male invariably gives

chink-chink calls in the evening in an (usually unsuccessful) attempt to deter other blackbirds from roosting in its territory overnight.

[24]

During the northern winter, blackbirds can be heard quietly singing to

themselves, so much so that September and October are the only months in

which the song cannot be heard.

[37] Like other passerine birds, it has a thin high

seee alarm call for threats from

birds of prey since the sound is rapidly attenuated in vegetation, making the source difficult to locate.

[38]

At least two subspecies,

T. m. merula and

T. m. nigropileus, will mimic other species of birds, cats, humans or alarms, but this is usually quiet and hard to detect.

Feeding

Adult male feeding on berries in

Lausanne, Switzerland

The common blackbird is

omnivorous, eating a wide range of

insects,

earthworms,

seeds and berries. It feeds mainly on the ground, running and hopping

with a start-stop-start progress. It pulls earthworms from the soil,

usually finding them by sight, but sometimes by hearing, and roots

through leaf litter for other

invertebrates. Small

amphibians and

lizards are occasionally hunted. This species will also perch in bushes to take berries and collect

caterpillars and other active insects.

[24]

Animal prey predominates, and is particularly important during the

breeding season, with windfall apples and berries taken more in the

autumn and winter. The nature of the fruit taken depends on what is

locally available, and frequently includes exotics in gardens.

Natural threats

A male attempting to distract a male

kestrel close to its nest

Near human habitation the main predator of the common blackbird is

the domestic cat, with newly fledged young especially vulnerable.

Foxes and predatory birds, such as the

sparrowhawk and other

accipiters, also take this species when the opportunity arises.

[39][40]

However, there is little direct evidence to show that either predation

of the adult blackbirds or loss of the eggs and chicks to

corvids, such as the

European magpie or

Eurasian jay, decrease population numbers.

[32]

This species is occasionally a host of

parasitic cuckoos, such as the

common cuckoo (

Cuculus canorus), but this is minimal because the common blackbird recognizes the adult of the parasitic species and its

non-mimetic eggs.

[41] In the UK, only three nests of 59,770 examined (0.005%) contained cuckoo eggs.

[42] The introduced

merula

blackbird in New Zealand, where the cuckoo does not occur, has, over

the past 130 years, lost the ability to recognize the adult common

cuckoo but still rejects non-mimetic eggs.

[43]

As with other passerine birds, parasites are common. 88% of common blackbirds were found to have

intestinal parasites, most frequently

Isospora and

Capillaria species.

[44] and more than 80% had haematozoan parasites (

Leucocytozoon,

Plasmodium,

Haemoproteus and

Trypanosoma species).

[45]

Common blackbirds spend much of their time looking for food on

the ground where they can become infested with ticks, which are external

parasites that most commonly attach to the head of a blackbird.

[46] In France, 74% of rural blackbirds were found to be infested with

Ixodes ticks, whereas, only 2% of blackbirds living in urban habitats were infested.

[46]

This is partly because it is more difficult for ticks to find another

host on lawns and gardens in urban areas than in uncultivated rural

areas, and partly because ticks are likely to be commoner in rural

areas, where a variety of tick hosts, such as foxes, deer and boar, are

more numerous.

[46] Although ixodid ticks can transmit

pathogenic viruses and bacteria, and are known to transmit

Borrelia bacteria to birds,

[47] there is no evidence that this affects the fitness of blackbirds except when they are exhausted and run down after migration.

[46]

The common blackbird is one of a number of species which has

unihemispheric slow-wave sleep. One hemisphere of the brain is effectively asleep, while a low-voltage

EEG,

characteristic of wakefulness, is present in the other. The benefit of

this is that the bird can rest in areas of high predation or during long

migratory flights, but still retain a degree of alertness.

[48]

Status and conservation

The

common blackbird has an extensive range, estimated at 10 million square

kilometres (3.8 million square miles), and a large population,

including an estimated 79 to 160 million individuals in Europe alone.

The species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the

population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more

than 30% in ten years or three generations), and is therefore evaluated

as

Least Concern.

[49] In the western

Palaearctic, populations are generally stable or increasing,

[15]

but there have been local declines, especially on farmland, which may

be due to agricultural policies that encouraged farmers to remove

hedgerows (which provide nesting places), and to drain damp grassland

and increase the use of

pesticides, both of which could have reduced the availability of invertebrate food.

[39]

The common blackbird was introduced to Australia by a bird dealer visiting

Melbourne in early 1857,

[50] and its range has expanded from its initial foothold in Melbourne and

Adelaide to include all of south-eastern Australia, including

Tasmania and the

Bass Strait islands.

[51]

The introduced population in Australia is considered a pest because it

damages a variety of soft fruits in orchards, parks and gardens

including berries, cherries, stone fruit and grapes.

[50] It is thought to spread weeds, such as

blackberry, and may compete with native birds for food and nesting sites.

[50][52]

The introduced common blackbird is, together with the native

silvereye (

Zosterops lateralis), the most widely distributed avian seed disperser in New Zealand. Introduced there along with the

song thrush (

Turdus philomelos)

in 1862, it has spread throughout the country up to an elevation of

1,500 metres (4,921 ft), as well as outlying islands such as the

Campbell and

Kermadecs.

[53]

It eats a wide range of native and exotic fruit, and makes a major

contribution to the development of communities of naturalised woody

weeds. These communities provide fruit more suited to non-endemic native

birds and naturalised birds, than to

endemic birds.

[54]

In culture

The common blackbird was seen as a sacred though destructive bird in

Classical Greek folklore, and was said to die if it consumed

pomegranate.

[55]

Like many other small birds, it has in the past been trapped in rural

areas at its night roosts as an easily available addition to the diet,

[56]

and in medieval times the practice of placing live birds under a pie

crust just before serving may have been the origin of the familiar

nursery rhyme:

[56]

Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye;

Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie!

When the pie was opened the birds began to sing,

Oh wasn't that a dainty dish to set before the king?[57]

The common blackbird's melodious, distinctive song is mentioned in the poem

Adlestrop by

Edward Thomas;

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.[58]

In the English

Christmas carol The Twelve Days of Christmas,

the line commonly sung today as "four calling birds" is believed to

have originally been written in the 18th century as "four colly birds",

an

archaism meaning "black as coal" that was a popular English nickname for the common blackbird.

[59]

The common blackbird, unlike many black creatures, is not normally seen as a symbol of bad luck,

[56] but

R. S. Thomas wrote that there is "a suggestion of dark Places about it",

[60] and it symbolised resignation in the 17th century

tragic play

The Duchess of Malfi;

[61] an alternate connotation is vigilance, the bird's clear cry warning of danger.

[61]

The common blackbird is the

national bird of Sweden,

[62] which has a breeding population of 1–2 million pairs,

[15] and was featured on a 30

öre Christmas postage stamp in 1970;

[63]

it has also featured on a number of other stamps issued by European and

Asian countries, including a 1966 4d British stamp and a 1998 Irish 30p

stamp.

[64] This bird—arguably—also gives rise to the

Serbian name for

Kosovo, which is the possessive adjectival form of Serbian

kos ("blackbird") as in

Kosovo Polje ("Blackbird Field").

[65]

A Common blackbird can be heard singing on

the Beatles song

Blackbird.

[66]

The famous Lebanese singer,

Sabah, one of the biggest recording and movie stars of the twentieth century in the

Arab World, was nicknamed the "blackbird of the valley" at the launch of her artistic career due to her beautiful voice.

[67]

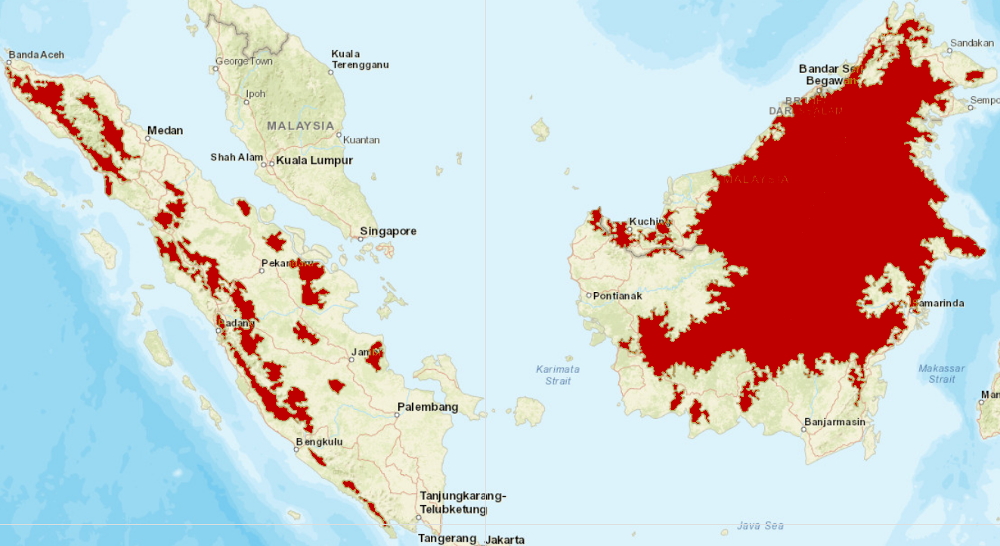

Turdus merula

Global range of the nominate subspecies based on reports to

eBird Year-round range Summer range Winter range