The South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris), also commonly called the Brazilian tapir (from the Tupi tapi'ira), the Amazonian tapir, the maned tapir, the lowland tapir, in Portuguese anta, and in mixed Quechua and Spanish sachavaca (literally "bushcow"), is one of the four widely recognized species in the tapir family, along with the mountain tapir, the Malayan tapir, and the Baird's tapir.[2] It is the largest surviving native terrestrial mammal in the Amazon.[3]

Most classifications systems include Tapirus kabomani (also known as the little black tapir or kabomani tapir), a disputed species, as part of Tapirus terrestris. The specific epithet derives from arabo kabomani, the word for tapir in the local Paumarí language. The formal description of this tapir did not suggest a common name for the species.[4] The Karitiana tribe call this the little black tapir.[5] It is the smallest tapir species, even smaller than the mountain tapir (T. pinchaque), which had been considered the smallest. T. kabomani is found in the Amazon rainforest, where it appears to be sympatric with the South American tapir (T. terrestris). When it was announced in December 2013, T. kabomani was the first odd-toed ungulate discovered in over 100 years. However, T. kabomani has not been recognized by the Tapir Specialist Group as a distinct species and recent genetic evidence further suggests it is actually nested within T. terrestris.[6][7]

Cristalino River, Brazil

Cristalino River, Brazil

Appearance

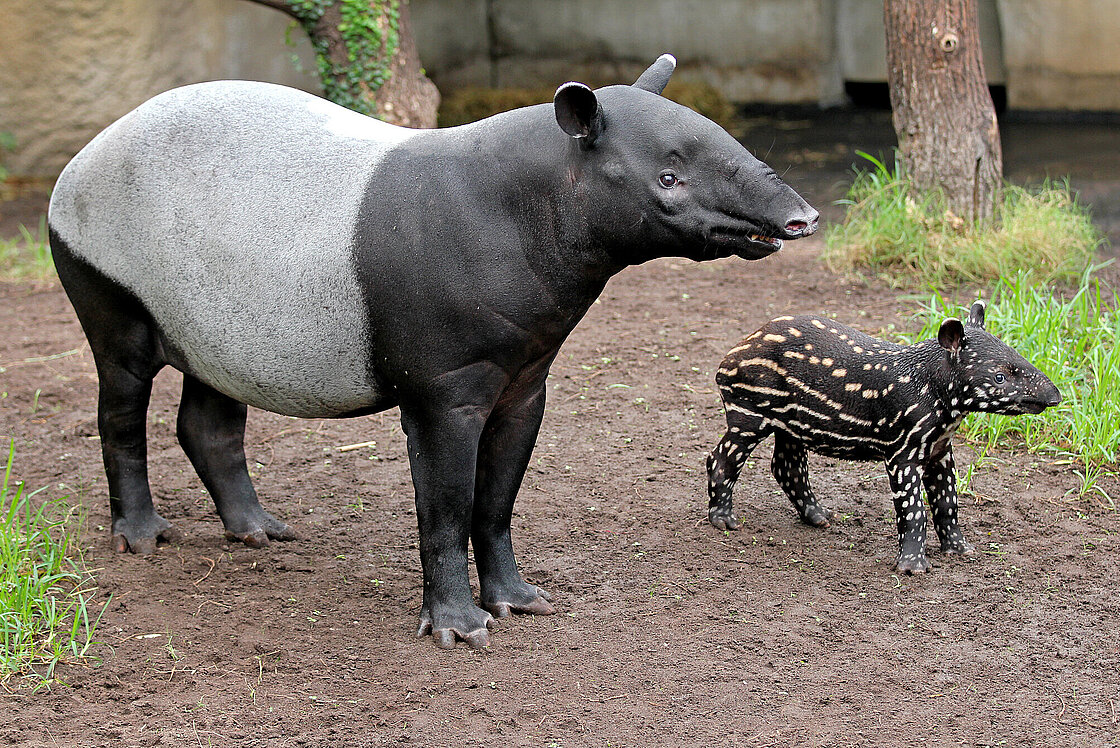

T. terrestris is dark brown, paler in the face, and has a low, erect crest running from the crown down the back of the neck. The round, dark ears have distinctive white edges. Newborn tapirs have a dark brown coat, with small white spots and stripes along the body. The South American tapir can attain a body length of 1.8 to 2.5 m (5.9 to 8.2 ft) with a 5 to 10 cm (2.0 to 3.9 in) short stubby tail and an average weight around 225 kg (496 lb). Adult weight has been reported ranging from 150 to 320 kg (330 to 710 lb). It stands somewhere between 77 to 108 cm (30 to 43 in) at the shoulder.[8]

Features claimed for Tapirus kabomani

With an estimated mass of only 110 kg (240 lb), T. kabomani is the smallest living tapir.[4] For comparison, the mountain tapir has a mass between 136 and 250 kg (300 and 551 lb).[9][10][11][12] Tapirus kabomani is roughly 130 centimetres (51 in) long and 90 centimetres (35 in) in shoulder height.[4]

It has a distinct phenotype from other members of the species. It can be differentiated by its coloration: it is a range of darker grey to brown than other T. terrestris strains.[4] This species also features relatively short legs for a tapir caused by a femur length that is shorter than dentary length.[4] The crest is smaller and less prominent.[5] T. kabomani also seems to exhibit some level of sexual dimorphism as females tend to be larger than males and possess a characteristic patch of light hair on their throats. The patch extends from the chin up to the ear and down to the base of the neck.[4]

Head and skull attributes are also important in identification of this species. This tapir possesses a single, narrow, low and gently inclined sagittal crest that rises posteriorly from the toothrow.[4] T. kabomani skulls also lack both a nasal septum and dorsal maxillary flanges.[4] The skull possesses a meatal diverticulum fossa that is shallower and less dorsally extended than those of the other four extant species of tapir.[4]

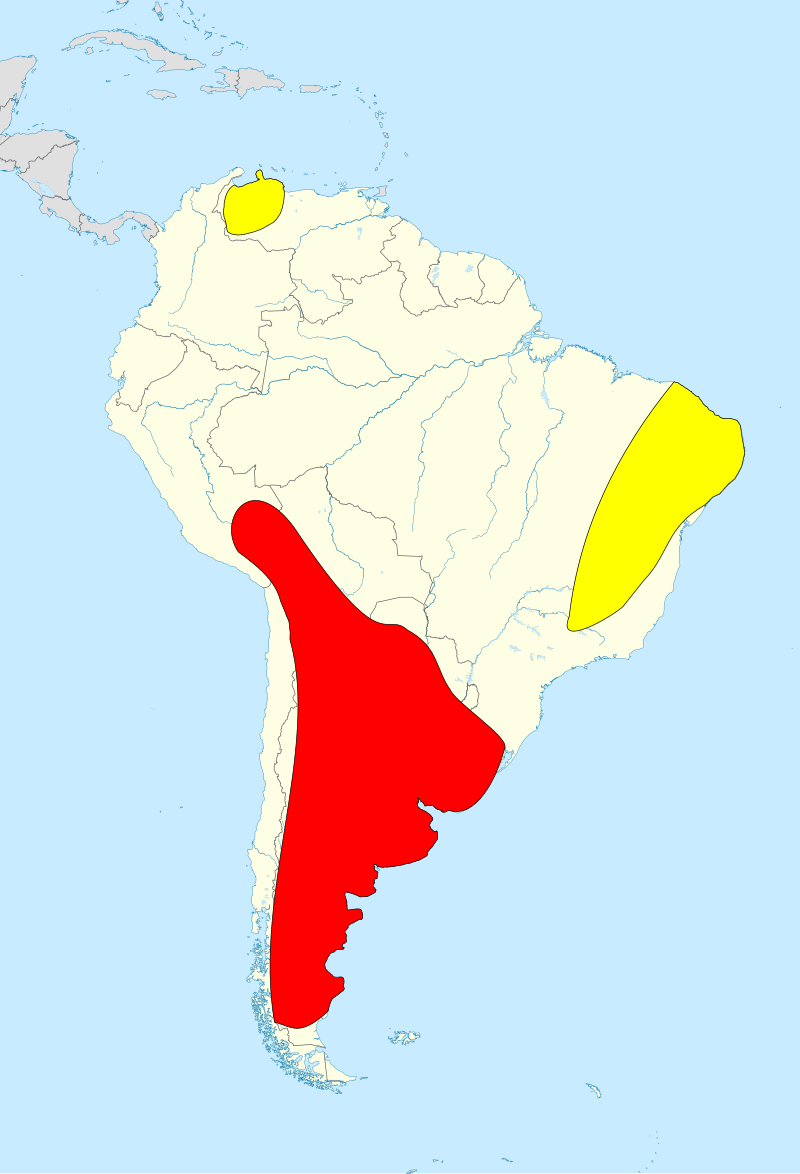

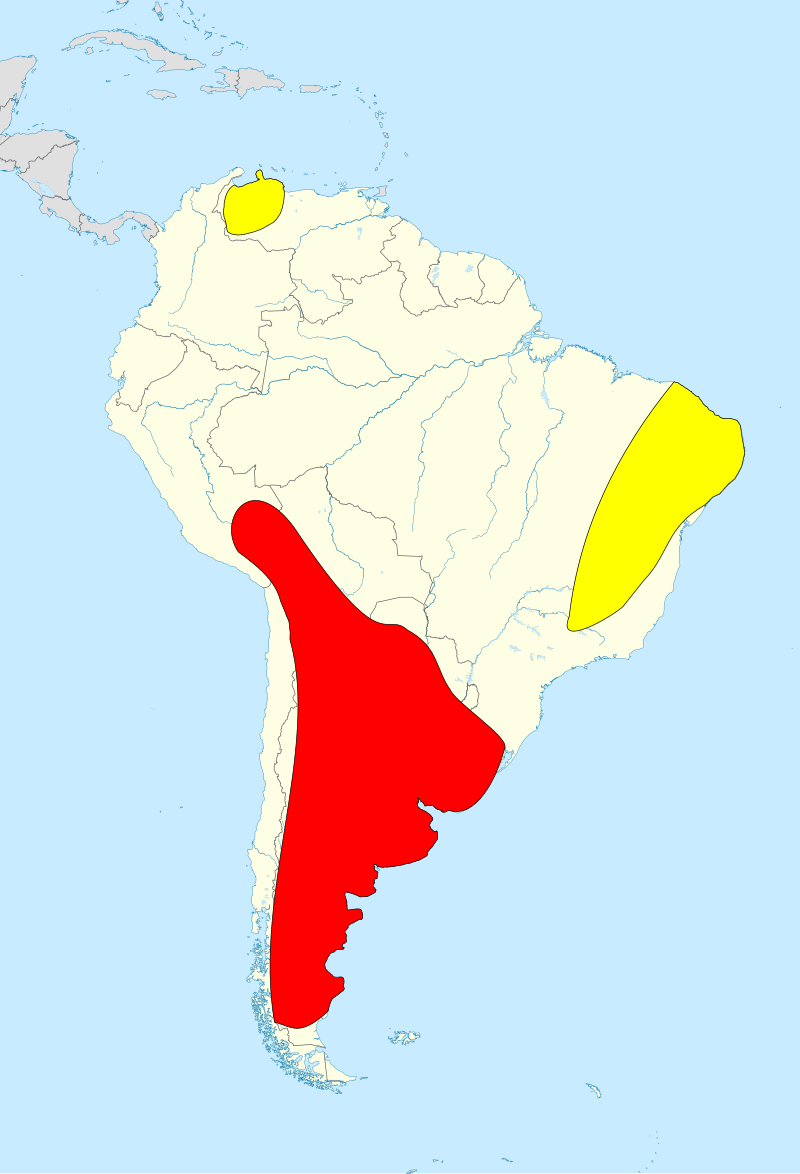

Geographic range

The South American tapir can be found near water in the Amazon Rainforest and River Basin in South America, east of the Andes. Its geographic range stretches from Venezuela, Colombia, and the Guianas in the north to Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay in the south, to Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador in the west.[13] On rare occasions, waifs have crossed the narrow sea channel from Venezuela to the southern coast of the island of Trinidad (but no breeding population exists there).

Tapirus kabomani is restricted to South America. It is found in habitats consisting of a mosaic of forest and savannah.[4] It has been collected in southern Amazonas (the type locality), Rondônia, and Mato Grosso states in Brazil. The species is also believed to be present in Amazonas department in Colombia, and it may be present in Amapá, Brazil, in north Bolivia[14] and in southern French Guiana.[5]

Behavior

T. terrestris is an excellent swimmer and diver, but also moves quickly on land, even over rugged, mountainous terrain. It has a life span of approximately 25 to 30 years. In the wild, its main predators are crocodilians (only the black caiman and Orinoco crocodile, the latter of which is critically endangered, are large enough to take these tapirs, as the American crocodile only exists in the northern part of South America) and large cats, such as the jaguar and cougar, which often attack tapirs at night when tapirs leave the water and sleep on the riverbank. The South American tapir is also attacked by the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus). T. terrestris is known to run to water when scared to take cover.

There is a need for more research to better explore social interactions.[15]

Diet

The South American tapir is an herbivore. Using its mobile nose, it feeds on leaves, buds, shoots, and small branches it tears from trees, fruit, grasses, and aquatic plants. They also feed on the vast majority of seeds found in the rainforest.[16] This is known because the diet is studied through observation of browsing, analysis of feces, and studying stomach contents.[17]

Although it has been determined via fecal samples that T. kabomani feeds on palm tree leaves and seeds from the genera Attalea and Astrocaryum, much about the diet and ecology of T. kabomani is unknown.[4] Previously discovered tapirs are known to be important seed disperses and to play key roles in the rainforest or mountain ecosystems in which they occur.[4] It is possible that T. kabomani shares this role with the other members of its genus although further research is required.

Mating

T. terrestris mates in April, May, or June, reaching sexual maturity in the third year of life. Females go through a gestation period of 13 months (390–395 days) and will typically have one offspring every two years. A newborn South American tapir weighs about 15 pounds (6.8 kilos) and will be weaned in about six months.

Endangered status

The dwindling numbers of the South American tapir are due to poaching for meat and hide, as well as habitat destruction. T. terrestris is generally recognized as an endangered animal species, with the species being designated as endangered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service on June 2, 1970.[18] It has a significantly lower risk of extinction, though, than the other four tapir species.

Conservation of T. kabomani

The species may be relatively common in forest-savanna mosaic habitat (relicts of former cerrado). Nevertheless, the species is threatened by prospects of future habitat loss related to deforestation, development and expanding human populations.[4]

While this tapir does not seem to be rare in the upper Madeira River region of the southwestern Brazilian Amazon,[4] its precise conservation status is unknown. T. kabomani is limited by its habitat preference and tends not to be found where its preferred mosaic gives way to either pure savannah or forest.[4] This, in combination with the fact that other less restricted tapir species within the area are already classified as endangered, has led scientists to hypothesize that the new species is likely to prove more endangered than other members of its genus.[5] Human population growth and deforestation within southwestern Amazonia threaten T. kabomani through habitat destruction.[4] The creation of infrastructure such as roads as well as two dams planned for the area as of December 2013 further threaten to considerably alter the home range.[5] Hunting is also a concern. The Karitiana tribe, a group of people indigenous to the area, regularly hunt the tapir.[5] Additional threats exist from crocodilians and jaguars, natural predators of tapirs within the area.[19]

Humans aside, the region of the Amazon in which T. kabomani is found has also been highlighted as an area that is likely to be particularly susceptible to global warming and the ecosystem changes it brings.[4]

History of classification

Although it was not formally described until 2013, the possibility that T. kabomani might be a distinct species had been suggested as early as 100 years prior. The first specimen recognized as a member of this species was collected on the Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition. Theodore Roosevelt (1914) believed they had collected a new species,[20] as local hunters recognized two types of tapir in the region[20] and another member of the expedition, Leo E. Miller, suggested that two species were present.[a] Nevertheless, though observed by experts, all tapirs from the expedition have been consistently treated as T. terrestris,[21][22] including specimen AMNH 36661, which is now identified as T. kabomani.[4] Ten years before T. kabomani was formally described, scientists suspected the existence of a new species while examining skulls that did not resemble the skulls of known tapir species.[23] When the species was formally described in December 2013,[4] it was the first tapir species described since T. bairdii in 1865.[5]

Relationships

In both morphological and molecular phylogenetic analyses,[4] T. kabomani was recovered as the first diverging of the three tapirs restricted to South America. Morphological analysis suggested that the closest relative of T. kabomani may be the extinct species T. rondoniensis.[4] Molecular dating methods based on three mitochondrial cytochrome genes gave an approximate divergence time of 0.5 Ma for T. kabomani and the T. terrestris–T. pinchaque clade, while T. pinchaque was found to have arisen within a paraphyletic T. terrestris complex much more recently (in comparison, the split between T. bairdii and the tapirs restricted to South America took place around 5 Ma ago).[4]

| Tapirus |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Controversy

The validity of the species, and whether or not it can be reliably distinguished from the South American tapir, has subsequently been questioned on both morphological and genetic grounds. Morphological differences between the two species of tapir are noted to be especially difficult to discern in photographs allegedly depicting T. kabomani and noted to be only qualitatively described in the original literature.[24] Morphologically, lack of published numerical ranges for diagnostic differences make it incredibly difficult for individuals to be identified in the field as little black tapirs instead of South American tapirs. A heavy reliance upon the indigenous people for identification of T. kabomani was also noted in the major dissenting article. Concerns were cited regarding the reliability of information when it is gathered from locals as, while they are frequently aware of many more species in an area, they can sometimes describe haplotypes of culturally important species to be entirely different species.[24]

Genetic evidence has been questioned on similar grounds. Several examined genetic sequences said to be characteristic for the species, most notably the Cyth sequence of cytochrome b, have been described as minimally divergent from those of other South American tapirs.[24] Further analyses of cytochrome b sequences did reveal a clade allegedly belonging to T. kabomani, however, it was described to be only as divergent as some haplotype found in other species.[24] Mitochondrial DNA originally connected to morphological traits and used to describe the species has also been called into question. Although several samples of T. kabomani have been obtained, only the two samples from southwestern Amazonia were analysed while those obtained in the northwest were not.[24] The connection between the morphology and DNA of supposed T. kabomani in northwestern areas is unknown and there is the possibility that the correlation between mtDNA and morphology is insufficiently supported.[24]

However, besides cytochrome b, two other mitochondrial genes were analyzed, COI and COII, both showing the same pattern found for cytochrome b.[25] Several other objections raised against the distinction of T. kabomani from T. terrestris, including external and internal morphological characters, statistical analysis, distribution and use of folk taxonomy, were addressed in Cozzuol et al (2014).[25]

Further genetic evidence invalidating T. kabomani as a new species was published by Ruiz-Garcia et al. (2016).[6] Ruiz-Garcia et al. found and sampled tapirs that fit the morphological description provided by Cozzuol et al. (2013) for T. kabomani but they only showed haplotypes of other T. terrestris haplogroups.[6] In addition, the morphological evidence for T. kabomani has been contradicted by further research.[26] Dumbá et al. reevaluated skull shape variation among tapir species and found that T. kabomani and T. terrestris exhibit considerable overlap in skull morphology, though it could still be distinguished by its broad forehead.[26]

Gallery

Young South American tapir at the Dortmund Zoo.

South American tapir in northern Peru.

South American tapir performing the Flehmen response.

Tapirus terrestris

South American tapir distribution

Extinct Extant Probably extant

/GettyImages-595710436-e9fb5588826f403193ff399bcc8c0d3d.jpg)