The

coypu (from

Spanish coipú, from

Mapudungun koypu;

[3][4] Myocastor coypus), also known as the

nutria,

[1][5] is a large,

herbivorous,

[6] semiaquatic

rodent.

Classified for a long time as the only member of the family Myocastoridae,

[7] Myocastor is now included within

Echimyidae, the family of the spiny rats.

[8][9][2]

The coypu lives in burrows alongside stretches of water, and feeds on river plant stems.

[10]

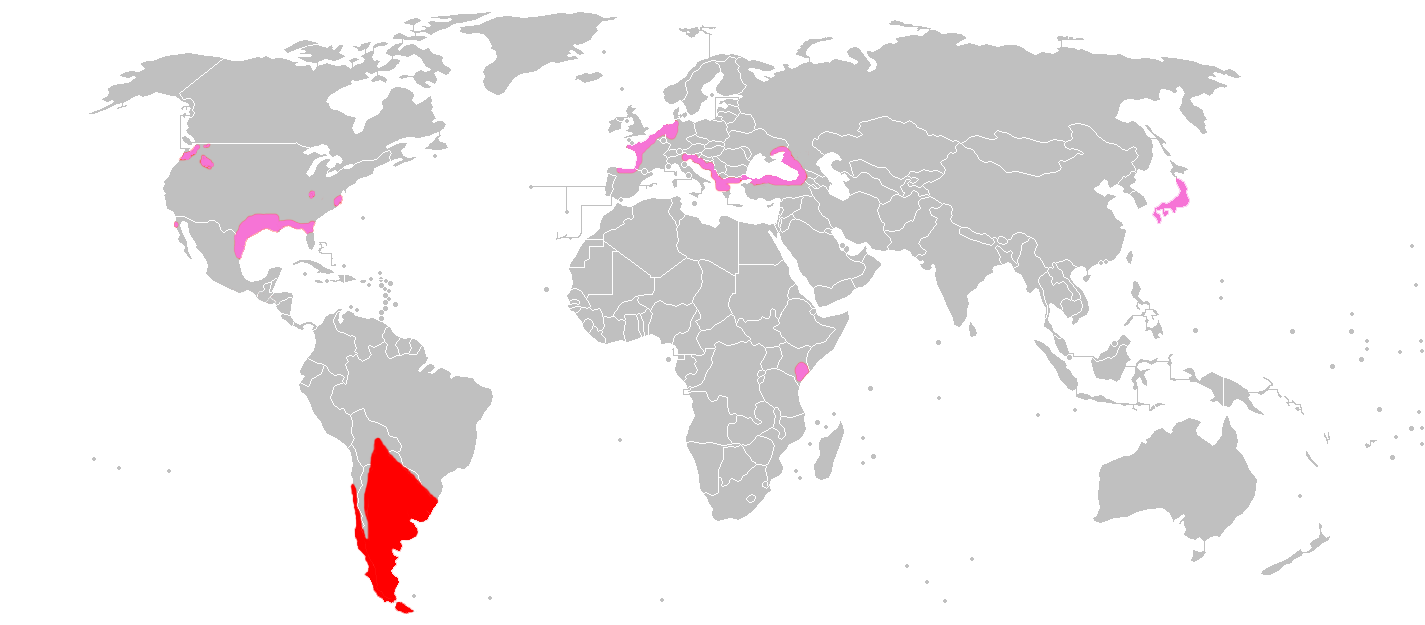

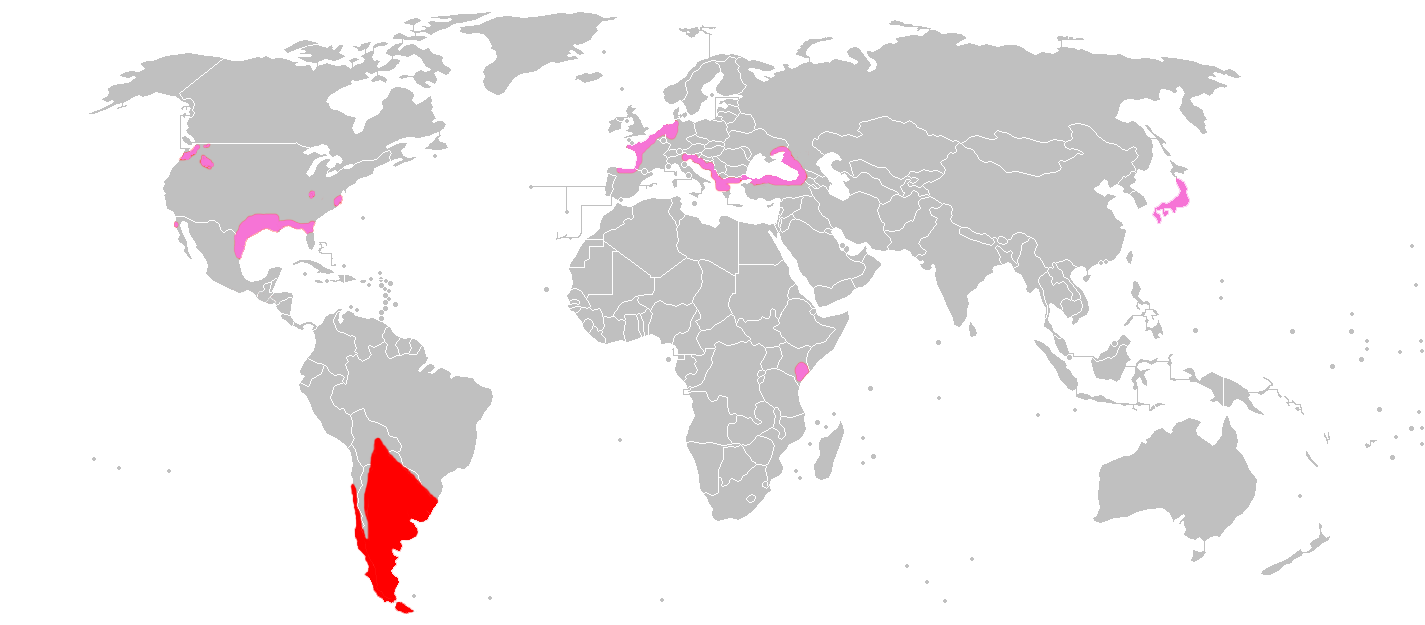

Originally native to subtropical and temperate South America, it has

since been introduced to North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa,

primarily by fur farmers.

[11] Although it is still hunted and trapped for

its fur

in some regions, its destructive burrowing and feeding habits often

bring it into conflict with humans, and it is considered an

invasive species.

[12]

Etymology

The genus name

Myocastor derives from the two

Ancient Greek words

μῦς (

mûs), meaning "rat, mouse", and

κάστωρ (

kástōr), meaning "beaver".

[13][14][15] Literally, therefore, the name

Myocastor means "beaver rat".

Two names are commonly used in

English for

Myocastor coypus. The name "nutria" (from Spanish word

nutria, meaning 'otter') is generally used in North America, Asia, and throughout

countries of the former Soviet Union; however, in most

Spanish-speaking countries, the word "nutria" refers primarily to the

otter. To avoid this ambiguity, the name "coypu" or "coipo" (derived from the

Mapudungun language) is used in Latin America and parts of Europe.

[16] In France, the coypu is known as a

ragondin. In Dutch, it is known as

beverrat (beaver rat). In German, it is known as

Nutria,

Biberratte (beaver rat), or

Sumpfbiber (swamp beaver). In Italy, instead, the popular name is, as in North America and Asia, "nutria", but it is also called

castorino ("little

beaver"), by which its fur is known in Italy. In Swedish, the animal is known as

sumpbäver (marsh/swamp beaver). In Brazil, the animal is known as

ratão-do-banhado (big swamp rat),

nútria, or

caxingui (the last from the

Tupi language).

Taxonomy

The coypu was first described by

Juan Ignacio Molina in 1782 as

Mus coypus, a member of the

mouse genus.

[17] The genus

Myocastor was assigned in 1792 by

Robert Kerr.

[18]

Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, independently of Kerr, named the species

Myopotamus coypus,

[19] and it is occasionally referred to by this name.

Four subspecies are generally recognized:

[17]

- M. c. bonariensis: northern Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, southern Brazil (RS, SC, PR, and SP)

- M. c. coypus: central Chile, Bolivia

- M. c. melanops: Chiloé Island

- M. c. santacruzae: Patagonia

M. c. bonariensis, the subspecies present in the northernmost

(subtropical) part of the coypu's range, is believed to be the type of

coypu most commonly introduced to other continents.

[16]

Phylogeny

Comparison of DNA and protein sequences showed that the genus

Myocastor is the sister group to the genus

Callistomys (painted tree-rats).

[20][2] In turn, these two taxa share evolutionary affinities with other

Myocastorini genera:

Proechimys and

Hoplomys (armored rats) on the one hand, and

Thrichomys on the other hand.

| Genus-level cladogram of the Myocastorini.

|

|

|

| The cladogram has been reconstructed from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA characters.[8][9][21][20][22][23][2]

|

Appearance

Large orange teeth are clearly visible on this coypu.

The coypu somewhat resembles a very large

rat, or a

beaver

with a small tail. Adults are typically 4–9 kg (8.8–19.8 lb) in weight,

and 40–60 cm (16–24 in) in body length, with a 30 to 45 cm (12 to 18

in) tail. It is possible for coypu to weigh up to 16 to 17 kg (35 to

37 lb), although adults usually average 4.5 to 7 kg (9.9 to 15.4 lb).

[24][25][26]

They have coarse, darkish brown outer fur with soft dense grey under

fur, also called the nutria. Three distinguishing features are a white

patch on the muzzle, webbed hind feet, and large, bright orange-yellow

incisors.

[27] The

nipples of female coypu are high on her flanks, to allow their young to feed while the female is in the water.

A coypu is often mistaken for a

muskrat,

another widely dispersed, semiaquatic rodent that occupies the same

wetland habitats. The muskrat, however, is smaller and more tolerant of

cold climates, and has a laterally flattened tail it uses to assist in

swimming, whereas the tail of a coypu is round. It can also be mistaken

for a small beaver, as beavers and coypus have very similar anatomies.

However, beavers' tails are flat and paddle-like, as opposed to the

round tails of coypus.

[28]

Life history

Coypus can live up to six years in captivity, but individuals

uncommonly live past three years old; according to one study, 80% of

coypus die within the first year, and less than 15% of a wild population

is over three years old.

[29]

Male coypus reach sexual maturity as early as four months, and females

as early as three months; however, both can have a prolonged

adolescence, up to the age of 9 months. Once a female is pregnant,

gestation

lasts 130 days, and she may give birth to as few as one or as many as

13 offspring. They generally line nursery nests with grasses and soft

reeds. Baby coypus are

precocial,

born fully furred and with open eyes; they can eat vegetation with

their parents within hours of birth. A female coypu can become pregnant

again the day after she gives birth to her young. If timed properly, a

female can become pregnant three times within a year. Newborn coypus

nurse for seven to eight weeks, after which they leave their mothers.

[30]

Habitat and feeding

A coypu in a canal in Milan

Besides breeding quickly, each coypu consumes large amounts of

vegetation. An individual consumes about 25% of its body weight daily,

and feeds year-round.

[30][31]

Being one of the world's larger extant rodents, a mature, healthy

coypu averages 5.4 kg (12 lb) in weight, but they can reach as much as

10 kg (22 lb).

[32][33] They eat the base of the above-ground stems of plants, and often dig through the organic soil for roots and

rhizomes to eat.

[34]

Their creation of "eat-outs", areas where a majority of the above- and

below-ground biomass has been removed, produces patches in the

environment, which in turn disrupts the habitat for other animals and

humans dependent on marshes.

[35]

Coypus are found most commonly in freshwater marshes, but also inhabit brackish marshes and rarely salt marshes.

[36][37] They either construct their own burrows, or occupy burrows abandoned by beaver, muskrats, or other animals.

[12] They are also capable of constructing floating rafts out of vegetation.

[12]

Commercial and environmental issues

Local extinction in their native range due to overharvesting led to

the development of coypu fur farms in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries. The first farms were in Argentina and then later in Europe,

North America, and Asia. These farms have generally not been successful

long-term investments, and farmed coypu often are released or escape as

operations become unprofitable. The first attempt at coypu farming was

in France in the early 1880s, but it was not much of a success.

[38] The first efficient and extensive coypu farms were located in South America in the 1920s.

[38]

The South American farms were very successful, and led to the growth of

similar farms in North America and Europe. Coypus from these farms

often escaped, or were deliberately released into the wild to provide a

game animal or to remove aquatic vegetation.

[39]

Coypus were introduced to the Louisiana ecosystem in the 1930s,

when they escaped from fur farms that had imported them from South

America. Coypu were released into the wild by at least one Louisiana

nutria farmer in 1933 and these releases were followed by

E. A. McIlhenny who released his entire stock in 1945 on Avery Island.

[40]

In 1940, some of the nutria escaped during a hurricane and quickly

populated coastal marshes, inland swamps, and other wetland areas.

[41] From Louisiana, coypus have spread across the Southern United States, wreaking havoc on marshland.

Following a decline in demand for coypu fur, coypu have since

become pests in many areas, destroying aquatic vegetation, marshes, and

irrigation

systems, and chewing through man-made items such as tires and wooden

house panelling in Louisiana, eroding river banks, and displacing native

animals. Damage in Louisiana has been sufficiently severe since the

1950s to warrant legislative attention; in 1958, the first bounty was

placed on nutria, though this effort was not funded.

[42]:3

By the early 2000s, the Coastwide Nutria Control Program was

established, which began paying bounties for nutria killed in 2002.

[42]:19–20 In the

Chesapeake Bay region in

Maryland,

where they were introduced in the 1940s, coypus are believed to have

destroyed 7,000 to 8,000 acres (2,800 to 3,200 ha) of marshland in the

Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. In response, by 2003, a multimillion-dollar eradication program was underway.

[43]

In the United Kingdom, coypus were introduced to

East Anglia, for fur, in 1929; many escaped and damaged the drainage works, and a concerted programme by

MAFF eradicated them by 1989.

[44] However, in 2012, a "giant rat" was killed in

County Durham, with authorities suspecting the animal was, in fact, a coypu.

[45]

Marsh Dog, a US company based in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, received

a grant from the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program to

establish a company that uses nutria meat for dog food products.

[46]

In 2012, the Louisiana Wildlife Federation recognized Marsh Dog with

"Business Conservationist of the Year" award for finding a use for this

ecosustainable protein.

[47]

In Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, nutria (Russian and local languages

Нутрия) are farmed on private plots and sold in local markets as a poor

man's meat.

[48] As of 2016, however, the meat is used successfully in Moscow restaurant Krasnodar Bistro, as part of the growing Russian

localvore movement and as a '

foodie' craze.

[48]

It appears on the menu as a burger, hotdog, dumplings, or wrapped in

cabbage leaves, with the flavour being somewhere between turkey and

pork.

[49]

In addition to direct environmental damage, coypus are the host for a

nematode parasite (

Strongyloides myopotami) that can infect the skin of humans, causing dermatitis similar to

strongyloidiasis.

[50] The condition is also called "nutria itch".

[51]

Distribution

Native

to subtropical and temperate South America, it has since been

introduced to North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa, primarily by fur

ranchers.

The distribution of coypus outside South America tends to contract or

expand with successive cold or mild winters. During cold winters, coypus

often suffer

frostbite

on their tails, leading to infection or death. As a result,

populations of coypus often contract and even become locally or

regionally

extinct as in the

Scandinavian countries and such US states as Idaho, Montana, and Nebraska during the 1980s.

[52]

During mild winters, their ranges tend to expand northward. For

example, in recent years, range expansions have been noted in Washington

and Oregon,

[53] as well as Delaware.

[54]

According to the

U.S. Geological Survey, nutria were first introduced to the United States in

California, in 1899. They were first brought to

Louisiana

in the early 1930s for the fur industry, and the population was kept in

check, or at a small population size, because of trapping pressure from

the fur traders.

[16]

The earliest account of nutria spreading freely into Louisiana wetlands

from their enclosures was in the early 1940s; a hurricane hit the

Louisiana coast for which many people were unprepared, and the storm

destroyed the enclosures, enabling the nutria to escape into the wild.

[16] According to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, nutria were also transplanted from

Port Arthur, Texas, to the

Mississippi River in 1941 and then spread due to a hurricane later that year.

[55]

Herbivory damage to wetlands

Nutria herbivory "severely reduces overall wetland biomass and can lead to the conversion of wetland to open water.

[31]

" Unlike other common disturbances in marshlands, such as fire and

tropical storms, which are a once- or few-times-a-year occurrence,

nutria feed year round, so their effects on the marsh are constant.

Also, nutria are typically more destructive in the winter than in the

growing season, due largely to the scarcity of above-ground vegetation;

as nutria search for food, they dig up root networks and rhizomes for

food.

[34] While nutria are the most common herbivores in Louisiana marshes, they are not the only ones. Feral hogs, also known as

wild boars (

Sus scrofa),

swamp rabbits (

Sylvilagus aquaticus), and

muskrats (

Ondatra zibethicus)

are less common, but feral hogs are increasing in number in Louisiana

wetlands. On plots open to nutria herbivory, 40% less vegetation was

found than in plots guarded against nutria by fences. This number may

seem insignificant, and indeed herbivory alone is not a serious cause of

land loss, but when herbivory was combined with an additional

disturbance, such as fire, single vegetation removal, or double

vegetation removal to simulate a tropical storm, the effect of the

disturbances on the vegetation were greatly amplified.

[31]

" Essentially, this means, as different factors were added together,

the result was less overall vegetation. Adding fertilizer to open plots

did not promote plant growth; instead, nutria fed more in the fertilized

areas. Increasing fertilizer inputs in marshes only increases nutria

biomass instead of the intended vegetation, therefore increasing

nutrient input is not recommended.

[31]

Wetlands in general are a valuable resource both economically and environmentally. For instance, the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

determined wetlands covered only 5% of the land surface of the

contiguous 48 United States, but they support 31% of the nation's plant

species.

[56]

These very biodiverse systems provide resources, shelter, nesting

sites, and resting sites (particularly Louisiana's coastal wetlands such

as

Grand Isle

for migratory birds) to a wide array of wildlife. Human users also

receive many benefits from wetlands, such as cleaner water, storm surge

protection, oil and gas resources (especially on the Gulf Coast),

reduced flooding, and chemical and biological waste reduction, to name a

few.

[56]

In Louisiana, rapid wetland loss occurs due to a variety of reasons;

this state loses an estimated area about the size of a football field

every hour. The problem became so serious that Sheriff

Harry Lee of

Jefferson Parish used

SWAT sharpshooters against the animals.

[58]

In 1998, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries

(LDWF) conducted the first Louisiana coast-wide survey, which was funded

by the

Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection, and Restoration Act and titled the Nutria Harvest and Wetland Demonstration Program, to evaluate the condition of the marshlands.

[59]

The survey revealed through aerial surveys of transects that herbivory

damage to wetlands totaled roughly 90,000 acres. The next year, LDWF

performed the same survey and found the area damaged by herbivory

increased to about 105,000 acres.

[36]

The LDWF has determined the wetlands affected by nutria decreased from

an estimated 80,000+ acres of Louisiana wetlands in 2002–2003 season to

about 6,296 acres during the 2010–2011 season.

[60]

The LDWF stresses that coastal wetland restoration projects will be

greatly hindered without effective, sustainable nutria population

control.

A claimed environmentally sound solution is the use of nutria meat to make dog food treats.

[61]

Control efforts

New Zealand

Coypus are classed as a "prohibited new organism" under New Zealand's

Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, preventing it from being imported into the country.

[62]

Great Britain

In

the UK, coypu escaped from fur farms and were reported in the wild as

early as 1932. There were three unsuccessful attempts to control coypu

in east Great Britain between 1943 and 1944. Coypu population and range

increased causing damage to agriculture in the 1950s. During the 1960s, a

grant was awarded to Rabbit Clearance Societies that included coypu.

This control allowed for the removal of 97,000 coypu in 1961 and 1962.

From 1962 to 1965, 12 trappers were hired to eradicate as many coypu as

possible near Norfolk Broads. The campaign used live traps allowing

non-target species to be released while any coypu caught were killed by

gun. Combined with cold winters in 1962 to 1963, almost 40,500 coypu

were removed from the population. Although coypu populations were

greatly reduced after the 1962-1965 campaign ended, the population

increased until another eradication campaign began in 1981. This

campaign succeeded in fully eradicating coypu in Great Britain. The

trapping areas were broken into 8 sectors leaving no area uncontrolled.

The 24 trappers were offered an incentive for early completion of the

10-year campaign. In 1989 coypu were assumed eradicated as only 3 males

were found between 1987 and 1989.

[63]

Ireland

A coypu was first sighted in the wild in Ireland in 2010.

Some coypu escaped from a pet farm in

Cork City in 2015 and began breeding on the outskirts of the city. Ten were trapped on the

Curraheen River in 2017, but the rodents continued to spread, reaching

Dublin via the

Royal Canal in 2019.

[64][65][66] Animals were found along the

River Mulkear

in 2015. The National Biodiversity Data Centre issued a species alert

in 2017, saying that coypu "[have] the potential to be a high impact

invasive species in Ireland. […] This species is listed as among 100 of

the worst invasive species in Europe."

[67]

Nutria herbivory "is perhaps the least studied or quantified aspect of wetland loss".

[59]

Many coastal restoration projects involve planting vegetation to

stabilize marshland, but this requires proper nutria control to be

successful.

Louisiana

The

Coastwide Nutria Control Program, provides incentives for harvesting

nutria. Starting in 2002, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries

(LDWF) has performed aerial surveys just as they had done for the

Nutria Harvest and Wetland Demonstration Program, only it is now under a

different program title. Under the Coastwide Nutria Control Program,

which also receives funds from

CWPPRA,

308,160 nutria were harvested the first year (2002–2003), revealing

82,080 acres damaged and totaling $1,232,640 in incentive payments paid

out to those legally participating in the program.

[60]

Essentially, once a person receives a license to hunt or trap nutria,

then that person is able to capture an unlimited number. When a nutria

is captured, the tail is cut off and turned in to a Coastal Environments

Inc. official at an approved site. Each nutria tail is worth $5, which

is an increase from $4 before the 2006–2007 season. Nutria harvesting

increased drastically during the 2009–2010 year, with 445,963 nutria

tails turned in worth $2,229,815 in incentive payments.

[60]

Each CEI official keeps record of how many tails have been turned in by

each individual per parish, the method used in capture of the nutria,

and the location of capture. All of this information is transferred to a

database to calculate the density of nutria across the Louisiana coast,

and the LDWF combines these data with the results from the aerial

surveys to determine the number of nutria remaining in the marshes and

the amount of damage they are inflicting on the ecosystem.

[60]

Another program executed by LDWF involves creating a market of

nutria meat for human consumption, though it is still trying to gain

public notice. Nutria is a very lean, protein-rich meat, low in fat and

cholesterol with the taste, texture, and appearance of rabbit or dark

turkey meat.

[68] Few

pathogens

are associated with the meat, but proper heating when cooking should

kill them. The quality of the meat and the minimal harmful

microorganisms associated with it make nutria meat an "excellent food

product for export markets".

[37]

Several desirable control methods are currently ineffective for various reasons.

Zinc phosphide

is the only rodenticide currently registered to control nutria, but it

is expensive, remains toxic for months, detoxifies in high humidity and

rain, and requires construction of (expensive) floating rafts for

placement of the chemical. It is not yet sure how many nontarget species

are susceptible to zinc phosphide, but birds and rabbits have been

known to die from ingestion.

[69]

Therefore, this chemical is rarely used, especially not in large-scale

projects. Other potential chemical pesticides would be required by the

US Environmental Protection Agency to undergo vigorous testing before

they could be acceptable to use on nutria. The LDWF has estimated costs

for new chemicals to be $300,000 for laboratory, chemistry, and field

studies, and $500,000 for a mandatory Environmental Impact Statement.

[69]

Contraception is not a common form of control, but is preferred by some

wildlife managers. It also is expensive to operate - an estimated $6

million annually to drop bait laced with birth-control chemicals.

Testing of other potential contraceptives would take about five to eight

years and $10 million, with no guarantee of FDA approval.

[69]

Also, an intensive environmental assessment would have to be completed

to determine whether any non-target organisms were affected by the

contraceptive chemicals. Neither of these control methods is likely to

be used in the near future.

[citation needed]

In Louisiana, a claimed environmentally sound solution is the killing of nutria to make dog food treats.

[61]

Atlantic coast

An eradication program on the

Delmarva Peninsula, between

Chesapeake Bay and the

Atlantic coast,

where they once numbered in the tens of thousands and had destroyed

thousands of acres of marshland, had nearly succeeded by 2012.

[70]

California

The first records of nutria invading California dates from the 1940s and 50s, when it was found in the agriculture-rich

Central Valley and the south coast of the state, but by the 1970s the animals had been extirpated statewide.

[71]. They were found again in

Merced County in 2017, on the edge of the

San Joaquin River Delta. State officials are concerned that they will harm infrastructure that sends water to

San Joaquin Valley farms and urban areas.

[72] In 2019, the

California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) received nearly $2 million in

Governor Gavin Newsom's first budget, and an additional $8.5 million via the

Delta Conservancy (a state agency focused on the Delta) to be spent over the course of three years.

[73] The state has adopted an eradication campaign based on the successful effort in the

Chesapeake Bay, including strategies such as the "

Judas nutria" (in which individualized nutria are caught, sterilized, fitted with

radio collars, and released, whereupon they can be tracked by hunters as they return to their colonies) and the use of trained dogs.

[73] The state has also reversed a prior "no-hunting" policy, although hunting the animals does require a license.

[73]

Gallery

-

Wild Coypu in Oise river in France

10-day-old baby coypu

Myocastor coypus

Coypu

range; native in red, introduced in pink