Owls hunt mostly small mammals, insects, and other birds, although a few species specialize in hunting fish. They are found in all regions of the Earth except Antarctica and some remote islands.

Owls are divided into two families: the Strigidae family of true (or typical) owls; and the Tytonidae family of barn-owls.

Anatomy

Burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia)

Captive short-eared owl chick at about 18 days old

Owls can rotate their heads and necks as much as 270°. Owls have 14 neck vertebrae compared to seven in humans, which makes their necks more flexible. They also have adaptations to their circulatory systems, permitting rotation without cutting off blood to the brain: the foramina in their vertebrae through which the vertebral arteries pass are about 10 times the diameter of the artery, instead of about the same size as the artery as in humans; the vertebral arteries enter the cervical vertebrae higher than in other birds, giving the vessels some slack, and the carotid arteries unite in a very large anastomosis or junction, the largest of any bird's, preventing blood supply from being cut off while they rotate their necks. Other anastomoses between the carotid and vertebral arteries support this effect.[1][2]

The smallest owl—weighing as little as 31 g (1 oz) and measuring some 13.5 cm (5 in)—is the elf owl (Micrathene whitneyi).[3] Around the same diminutive length, although slightly heavier, are the lesser known long-whiskered owlet (Xenoglaux loweryi) and Tamaulipas pygmy owl (Glaucidium sanchezi).[3] The lsrgest owls are two similarly sized eagle owls; the Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) and Blakiston's fish owl (Bubo blakistoni). The largest females of these species are 71 cm (28 in) long, have 54 cm (21 in) long wings, and weigh 4.2 kg (9.3 lb).[3][4][5][6][7]

Different species of owls produce different sounds; this distribution of calls aids owls in finding mates or announcing their presence to potential competitors, and also aids ornithologists and birders in locating these birds and distinguishing species. As noted above, their facial discs help owls to funnel the sound of prey to their ears. In many species, these discs are placed asymmetrically, for better directional location.

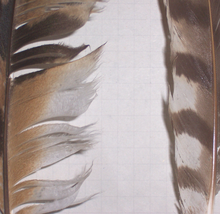

Owl plumage is generally cryptic, although several species have facial and head markings, including face masks, ear tufts, and brightly coloured irises. These markings are generally more common in species inhabiting open habitats, and are thought to be used in signaling with other owls in low-light conditions.[8]

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is a physical difference between males and females of a species. Reverse sexual dimorphism, when females are larger than males, has been observed across multiple owl species.[9] The degree of size dimorphism varies across multiple populations and species, and is measured through various traits, such as wing span and body mass.[9] Overall, female owls tend to be slightly larger than males. The exact explanation for this development in owls is unknown. However, several theories explain the development of sexual dimorphism in owls.One theory suggests that selection has led males to be smaller because it allows them to be efficient foragers. The ability to obtain more food is advantageous during breeding season. In some species, female owls stay at their nest with their eggs while it is the responsibility of the male to bring back food to the nest.[10] However, if food is scarce, the male first feeds himself before feeding the female.[11] Small birds, which are agile, are an important source of food for owls. Male burrowing owls have been observed to have longer wing chords than females, despite being smaller than females.[11] Furthermore, owls have been observed to be roughly the same size as their prey.[11] This has also been observed in other predatory birds,[10] which suggests that owls with smaller bodies and long wing chords have been selected for because of the increased agility and speed that allows them to catch their prey.

Another popular theory suggests that females have not been selected to be smaller like male owls because of their sexual roles. In many species, female owls may not leave the nest. Therefore, females may have a larger mass to allow them to go for a longer period of time without starving. For example, one hypothesized sexual role is that larger females are more capable of dismembering prey and feeding it to their young, hence female owls are larger than their male counterparts.[9]

A different theory suggests that the size difference between male and females is due to sexual selection: since large females can choose their mate and may violently reject a male's sexual advances, smaller male owls that have the ability to escape unreceptive females are more likely to have been selected.[11]

Adaptations for hunting

All owls are carnivorous birds of prey and live mainly on a diet of insects and small rodents such as mice, rats, and hares. Some owls are also specifically adapted to hunt fish. They are very adept in hunting in their respective environments. Since owls can be found in nearly all parts of the world and across a multitude of ecosystems, their hunting skills and characteristics vary slightly from species to species, though most characteristics are shared among all species.[citation needed]Flight and feathers

Most owls share an innate ability to fly almost silently and also more slowly in comparison to other birds of prey. Most owls live a mainly nocturnal lifestyle and being able to fly without making any noise gives them a strong advantage over their prey that are listening for the slightest sound in the night. A silent, slow flight is not as necessary for diurnal and crepuscular owls given that prey can usually see an owl approaching. While the morphological and biological mechanisms of this silent flight are more or less unknown, the structure of the feather has been heavily studied and accredited to a large portion of why they have this ability. Owls’ feathers are generally larger than the average birds’ feathers, have fewer radiates, longer pennulum, and achieve smooth edges with different rachis structures.[12] Serrated edges along the owl’s remiges bring the flapping of the wing down to a nearly silent mechanism. The serrations are more likely reducing aerodynamic disturbances, rather than simply reducing noise.[12] The surface of the flight feathers is covered with a velvety structure that absorbs the sound of the wing moving. These unique structures reduce noise frequencies above 2 kHz,[13] making the sound level emitted drop below the typical hearing spectrum of the owl’s usual prey[13][14] and also within the owl’s own best hearing range.[citation needed] This optimizes the owl’s ability to silently fly to capture prey without the prey hearing the owl first as it flies in. It also allows the owl to monitor the sound output from its flight pattern.Vision

Eyesight is a particular characteristic of the owl that aids in nocturnal prey capture. Owls are part of a small group of birds that live nocturnally, but do not use echolocation to guide them in flight in low-light situations. Owls are known for their disproportionally large eyes in comparison to their skulls. An apparent consequence of the evolution of an absolutely large eye in a relatively small skull is that the eye of the owl has become tubular in shape. This shape is found in other so-called nocturnal eyes, such as the eyes of strepsirrhine primates and bathypelagic fishes.[16] Since the eyes are fixed into these sclerotic tubes, they are unable to move the eyes in any direction.[17] Instead of moving their eyes, owls swivel their heads to view their surroundings. Owls' heads are capable of swiveling through an angle of roughly 270°, easily enabling them to see behind them without relocating the torso.[17] This ability keeps bodily movement at a minimum, thus reduces the amount of sound the owl makes as it waits for its prey. Owls are regarded as having the most frontally placed eyes among all avian groups, which gives them some of the largest binocular fields of vision. However, owls are farsighted and cannot focus on objects within a few centimeters of their eyes.[16][18] While owls are commonly believed to have great nocturnal vision due to their large (thus very light-gathering) eyes and pupils and/or extremely sensitive rod receptors, the true cause for their ability to see in the night is due to neural mechanisms which mediate the extraction of spatial information gathered from the retinal image throughout the nocturnal luminance range. These mechanisms are only able to function due to the large-sized retinal image.[19] Thus, the primary nocturnal function in the vision of the owl is due to its large posterior nodal distance; retinal image brightness is only maximized to the owl within secondary neural functions.[19] These attributes of the owl cause its nocturnal eyesight to be far superior to that of its average prey.[19]Hearing

The prominences above a great horned owl's head are commonly mistaken as its ears. This is not the case; they are merely feather tufts. The ears are on the sides of the head in the usual location (in two different locations as described above).

Talons

While the auditory and visual capabilities of the owl allow it to locate and pursue its prey, the talons and beak of the owl do the final work. The owl kills its prey using these talons to crush the skull and knead the body.[17] The crushing power of an owl’s talons varies according to prey size and type, and by the size of the owl. The burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), a small, partly insectivorous owl, has a release force of only 5 N. The larger barn owl (Tyto alba) needs a force of 30 N to release its prey, and one of the largest owls, the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) needs a force over 130 N to release prey in its talons.[21] An owl’s talons, like those of most birds of prey, can seem massive in comparison to the body size outside of flight. The masked owl has some of the proportionally longest talons of any bird of prey; they appear enormous in comparison to the body when fully extended to grasp prey.[22] An owl’s claws are sharp and curved. The family Tytonidae has inner and central toes of about equal length, while the family Strigidae has an inner toe that is distinctly shorter than the central one.[21] These different morphologies allow efficiency in capturing prey specific to the different environments they inhabit.Beak

The beak of the owl is short, curved, and downward-facing, and typically hooked at the tip for gripping and tearing its prey. Once prey is captured, the scissor motion of the top and lower bill is used to tear the tissue and kill. The sharp lower edge of the upper bill works in coordination with the sharp upper edge of the lower bill to deliver this motion. The downward-facing beak allows the owl’s field of vision to be clear, as well as directing sound into the ears without deflecting sound waves away from the face.[citation needed]

Snowy owl blends well with its snowy surroundings

Camouflage

The coloration of the owl’s plumage plays a key role in its ability to sit still and blend into the environment, making it nearly invisible to prey. Owls tend to mimic the colorations and sometimes even the texture patterns of their surroundings, the common barn owl being an exception. Nyctea scandiaca, or the snowy owl, appears nearly bleach-white in color with a few flecks of black, mimicking their snowy surroundings perfectly. Likewise, the mottled wood-owl (Strix ocellata) displays shades of brown, tan, and black, making the owl nearly invisible in the surrounding trees, especially from behind. Usually, the only tell-tale sign of a perched owl is its vocalizations or its vividly colored eyes.Behavior

Comparison of an owl (left) and hawk (right) remex.

The serrations on the leading edge of an owl's flight feathers reduce noise

Owl eyes each have nictitating membranes that can move independently of each other, as seen on this spotted eagle-owl in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Much of the owls' hunting strategy depends on stealth and surprise. Owls have at least two adaptations that aid them in achieving stealth. First, the dull coloration of their feathers can render them almost invisible under certain conditions. Secondly, serrated edges on the leading edge of owls' remiges muffle an owl's wing beats, allowing an owl's flight to be practically silent. Some fish-eating owls, for which silence has no evolutionary advantage, lack this adaptation.

An owl's sharp beak and powerful talons allow it to kill its prey before swallowing it whole (if it is not too big). Scientists studying the diets of owls are helped by their habit of regurgitating the indigestible parts of their prey (such as bones, scales, and fur) in the form of pellets. These "owl pellets" are plentiful and easy to interpret, and are often sold by companies to schools for dissection by students as a lesson in biology and ecology.[23]

Breeding and reproduction

Owl eggs typically have a white colour and an almost spherical shape, and range in number from a few to a dozen, depending on species and the particular season; for most, three or four is the more common number. In at least one species, female owls do not mate with the same male for a lifetime. Female burrowing owls commonly travel and find other mates, while the male stays in his territory and mates with other females.[24]Evolution and systematics

Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) sleeping during daytime in a hollow tree

Some 220 to 225 extant species of owls are known, subdivided into two families: typical owls (Strigidae) and barn-owls (Tytonidae). Some entirely extinct families have also been erected based on fossil remains; these differ much from modern owls in being less specialized or specialized in a very different way (such as the terrestrial Sophiornithidae). The Paleocene genera Berruornis and Ogygoptynx show that owls were already present as a distinct lineage some 60–57 million years ago (Mya), hence, possibly also some 5 million years earlier, at the extinction of the nonavian dinosaurs. This makes them one of the oldest known groups of non-Galloanserae landbirds. The supposed "Cretaceous owls" Bradycneme and Heptasteornis are apparently nonavialan maniraptors.[26]

During the Paleogene, the Strigiformes radiated into ecological niches now mostly filled by other groups of birds.[clarification needed] The owls as known today, though, evolved their characteristic morphology and adaptations during that time, too. By the early Neogene, the other lineages had been displaced by other bird orders, leaving only barn-owls and typical owls. The latter at that time were usually a fairly generic type of (probably earless) owls similar to today's North American spotted owl or the European tawny owl; the diversity in size and ecology found in typical owls today developed only subsequently.

Around the Paleogene-Neogene boundary (some 25 Mya), barn-owls were the dominant group of owls in southern Europe and adjacent Asia at least; the distribution of fossil and present-day owl lineages indicates that their decline is contemporary with the evolution of the different major lineages of typical owls, which for the most part seems to have taken place in Eurasia. In the Americas, rather an expansion of immigrant lineages of ancestral typical owls occurred.

The supposed fossil herons "Ardea" perplexa (Middle Miocene of Sansan, France) and "Ardea" lignitum (Late Pliocene of Germany) were more probably owls; the latter was apparently close to the modern genus Bubo. Judging from this, the Late Miocene remains from France described as "Ardea" aureliensis should also be restudied.[27] The Messelasturidae, some of which were initially believed to be basal Strigiformes, are now generally accepted to be diurnal birds of prey showing some convergent evolution towards owls. The taxa often united under Strigogyps[28] were formerly placed in part with the owls, specifically the Sophiornithidae; they appear to be Ameghinornithidae instead.[29][30][31]

The ancient fossil owl Palaeoglaux artophoron

Unresolved and basal forms (all fossil)

- Berruornis (Late Paleocene of France) basal? Sophornithidae?

- Strigiformes gen. et ap. indet. (Late Paleocene of Zhylga, Kazakhstan)

- Palaeoglaux (Middle – Late Eocene of WC Europe) own family Palaeoglaucidae or Strigidae?

- Palaeobyas (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene of Quercy, France) Tytonidae? Sophiornithidae?

- Palaeotyto (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene of Quercy, France) Tytonidae? Sophiornithidae?

- Strigiformes gen. et spp. indet. (Early Oligocene of Wyoming, USA)[27]

Ogygoptyngidae

- Ogygoptynx (Middle/Late Paleocene of Colorado, USA)

Protostrigidae

- Eostrix (Early Eocene of WC USA and England – Middle Eocene of WC USA)

- Minerva (Middle – Late Eocene of W USA) formerly Protostrix, includes "Aquila" ferox, "Aquila" lydekkeri, and "Bubo" leptosteus

- Oligostrix (mid-Oligocene of Saxony, Germany)

Sophiornithidae

- Sophiornis

Tytonidae: barn-owls

Barn owl (Tyto alba)

- Genus Tyto – typical barn-owls, stand up to 500 millimetres (20 in) tall. Some 15 species and possibly one recently extinct.

- Genus Phodilus – bay-owls, 2–3 extant species and possibly one recently extinct.

- Nocturnavis (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene) includes "Bubo" incertus

- Selenornis (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene) – includes "Asio" henrici

- Necrobyas (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene – Late Miocene) includes "Bubo" arvernensis and Paratyto

- Prosybris (Early Oligocene? – Early Miocene)

- Tytonidae gen. et sp. indet. "TMT 164" (Middle Miocene) – Prosybris?

Strigidae: typical owls

Long-eared owl (Asio otus) in erect pose

Laughing owl (Sceloglaux albifacies), last seen in 1914

- Aegolius – saw-whet owls, four species

- Asio – eared owls, 6–7 species

- Athene – 2–4 species (depending on whether Speotyto and Heteroglaux are included or not)

- Bubo – horned owls, eagle-owls and fish-owls; paraphyletic with Nyctea, Ketupa, and Scotopelia, some 25 species

- Ciccaba – four species

- Glaucidium – pygmy-owls, about 30–35 species

- Grallistrix – stilt-owls, four species; prehistoric

- Gymnoglaux – bare-legged owl or Cuban screech-owl

- Jubula – maned owl

- Lophostrix – crested owl

- Mascarenotus – Mascarene owls, three species; extinct (c. 1850)

- Megascops – screech-owls, some 20 species

- Micrathene – elf owl

- Ninox – Australasian hawk-owls, some 20 species

- Nesasio – fearful owl

- Ornimegalonyx – Caribbean giant owls, 1–2 species; prehistoric

- Otus – scops owls; probably paraphyletic, about 45 species

- Pseudoscops – Jamaican owl and possibly striped owl

- Ptilopsis – white-faced owls, two species

- Pulsatrix – spectacled owls, three species

- Pyrroglaux – Palau owl

- Sceloglaux – laughing owl; extinct (1914?)

- Strix – earless owls, about 15 species

- Surnia – northern hawk-owl

- Uroglaux – Papuan hawk-owl

- Xenoglaux – long-whiskered owlet

- Mioglaux (Late Oligocene? – Early Miocene of WC Europe) – includes "Bubo" poirreiri

- Intutula (Early/Middle – ?Late Miocene of C Europe) – includes "Strix/Ninox" brevis

- Alasio (Middle Miocene of Vieux-Collonges, France) – includes "Strix" collongensis

- Oraristrix (Late Pleistocene)

- "Otus/Strix" wintershofensis: fossil (Early/Middle Miocene of Wintershof West, Germany) – may be close to extant genus Ninox[27]

- "Strix" edwardsi – fossil (Middle/Late? Miocene)

- "Asio" pygmaeus – fossil (Early Pliocene of Odessa, Ukraine)

- Strigidae gen. et sp. indet. UMMP V31030 (Late Pliocene) – Strix/Bubo?

- Ibiza owl, Strigidae gen. et sp. indet. – prehistoric[32]

Symbolism and mythology

A little owl, probably Lilith's owl.

African cultures

Among the Kikuyu of Kenya, it was believed that owls were harbingers of death. If one saw an owl or heard its hoot, someone was going to die. In general, owls are viewed as harbingers of bad luck, ill health, or death. The belief is widespread even today.[33]

The Little Owl, 1506, by Albrecht Dürer

Asia

In Mongolia the owl is regarded as a benign omen. The great warlord Genghis Khan was hiding from enemies in a small coppice. An owl roosted in the tree above him, which caused his pursuers to think no man could be hidden there.[34]In modern Japan, owls are regarded as lucky and are carried in the form of a talisman or charm.[35]

Ancient European and modern Western culture

Owl-shaped protocorinthian aryballos, c. 640 BC, from Greece

Roman owl mosaic from Italica, Spain

Manises

plate, circa 1535. A fantastical owl wearing a crown, a characteristic

Manises design during the first half of the 16th century.

T. F. Thiselton-Dyer in his Folk-lore of Shakespeare says that "from the earliest period it has been considered a bird of ill-omen," and Pliny tells us how, on one occasion, even Rome itself underwent a lustration, because one of them strayed into the Capitol. He represents it also as a funereal bird, a monster of the night, the very abomination of human kind. Virgil describes its death-howl from the top of the temple by night, a circumstance introduced as a precursor of Dido's death. Ovid, too, constantly speaks of this bird's presence as an evil omen; and indeed the same notions respecting it may be found among the writings of most of the ancient poets."[38] A list of "omens drear" in John Keats' Hyperion includes the "gloom-bird's hated screech."[39] Pliny the Elder reports that owl's eggs were commonly used as a hangover cure.[40]

Hinduism

the Hindu Goddess Lakshmi with the owl

Native American cultures

People often allude to the reputation of owls as bearers of supernatural danger when they tell misbehaving children, "the owls will get you",[41] and in most Native American folklore, owls are a symbol of death. For example:- According to Apache and Seminole tribes, hearing owls hooting is considered the subject of numerous "bogeyman" stories told to warn children to remain indoors at night or not cry too much, otherwise the owl may carry them away.[42][43] In some tribal legends, owls are associated with spirits of the dead, and the bony circles around an owl's eyes are said to comprise the fingernails of apparitional humans. Sometimes owls are said to carry messages from beyond the grave or deliver supernatural warnings to people who have broken tribal taboos.[44]

- The Aztecs and Maya, along with other natives of Mesoamerica, considered the owl a symbol of death and destruction. In fact, the Aztec god of death, Mictlantecuhtli, was often depicted with owls.[45] There is an old saying in Mexico that is still in use:[46] Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere ("When the owl cries/sings, the Indian dies"). The Popol Vuh, a Mayan religious text, describes owls as messengers of Xibalba (the Mayan "Place of Fright").[47]

- The belief that owls are messengers and harbingers of the dark powers is also found among the Hočągara (Winnebago) of Wisconsin.[48] When in earlier days the Hočągara committed the sin of killing enemies while they were within the sanctuary of the chief's lodge, an owl appeared and spoke to them in the voice of a human, saying, "From now on the Hočągara will have no luck." This marked the beginning of the decline of their tribe.[49] An owl appeared to Glory of the Morning, the only female chief of the Hočąk nation, and uttered her name. Soon afterwards she died.[50][51]

- According to the culture of the Hopi, a Uto-Aztec tribe, taboos surround owls, which are associated with sorcery and other evils.

- Ojibwe tribes, as well as their Aboriginal Canadian counterparts, used an owl as a symbol for both evil and death. In addition, they used owls as a symbol of very high status of spiritual leaders of their spirituality.[52]

- Pawnee tribes viewed owls as the symbol of protection from any danger within their realms.[52]

- Pueblo people associated owls with Skeleton Man, the god of death and spirit of fertility.[52]

- Yakama tribes use an owl as a powerful totem. Such taboos or totems often guide where and how forests and natural resources are useful with management, even to this day and even with the proliferation of "scientific" forestry on reservations.[52]

Use as rodent control

A purpose-built owl-house or owlery at a farm near Morton on the Hill, England (2006)