The sun bear is also known as the "honey bear", which refers to its voracious appetite for honeycombs and honey.[2] However, "honey bear" can also refer to a kinkajou, which is an unrelated member of the Procyonidae.

Characteristics

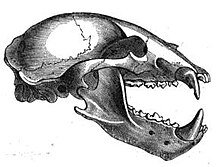

Sun bear skull

The sun bear is the smallest of the bear species. Adults are about 120–150 cm (47–59 in) long and weigh 27–80 kg (60–176 lb). Males are 10–20% larger than females. Their muzzles are short and light-coloured, and in most cases, the white area extends above the eyes. Their paws are large, and the soles are fur-less, which is thought to be an adaptation for climbing trees. Their claws are large, curved, and pointed.[3][5][6] The sun bear's claws are sickle-shaped; the front paw claws are long and heavy. The tail is 30–70 mm (1.2–2.8 in) long.[7]

During feeding, the sun bear can extend its exceptionally long tongue 20–25 cm (7.9–9.8 in) to extract insects and honey.[8] The sun bear's teeth are very large, especially canines, and high bite forces in relation to its body size, which are not well understood, but could be related to its frequent opening of tropical hardwood trees (with its powerful jaws and claws) in pursuit of insects, larvae, or honey.[9] The animal's entire head is also large, broad, and heavy in proportion to the body, and the palate is wide in proportion to the skull. The overall morphology of this bear (inward-turned front feet, ventrally flattened chest, powerful forelimbs with large claws) indicates adaptation for extensive climbing.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Sun bears are found in the tropical rainforest of Southeast Asia ranging from northeastern India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam to southern Yunnan Province in China, and on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo in Indonesia. They now occur very patchily through much of their former range, and have been extirpated from many areas, especially in mainland Southeast Asia. Their current distribution in eastern Myanmar and most of Yunnan is unknown.[1] The bear’s habitat is associated with tropical evergreen forests.[10]Distribution of subspecies

- The Malayan sun bear (H. m. malayanus (Raffles, 1821)) occurs on the Asian mainland and Sumatra.[11]

- The Bornean sun bear (H. m. euryspilus (Horsfield, 1825)) occurs only on the island of Borneo.[12]

Ecology and behavior

As sun bears occur in tropical regions with year-round available foods, they do not hibernate. Except for females with their offspring, they are usually solitary.[1] Male sun bears are primarily diurnal, but some are active at night for short periods. Bedding sites consist mainly of fallen hollow logs, but they also rest in standing trees with cavities, in cavities underneath fallen logs or tree roots, and in tree branches high above the ground.[13]In captivity, they exhibit social behavior, and sleep mostly during the day.[14]

Sun bears are known as very fierce animals when surprised in the forest.[3]

Diet

A sun bear in Shanghai Zoo showing its powerful jaws

Sun bear scats collected in a forest reserve in Sabah contained mainly invertebrates such as beetles and their larvae, termites, and ants, followed by fruits and vertebrates. They break open decayed wood in search of termites, beetle larvae, and earthworms, and use their claws and teeth to break the standing termite mound into a few pieces. They quickly lick and suck the contents from the exposed mound, and also hold pieces of the broken mound with their front paws, while licking the termites from the surface of the mound. They consume figs in large amounts and eat them whole. Vertebrates consumed comprise birds, eggs, reptiles, turtles, deer and several unidentified small vertebrates.[17] Hair or bone remains are rarely found in sun bear scat.[18]

They can crack open nuts with their powerful jaws. Much of their food must be detected using their keen sense of smell.[citation needed]

Reproduction

Females are observed to mate at about 3 years of age. During time of mating, the sun bear shows behaviours such as hugging, mock fighting, and head bobbing with its mate.Gestation has been reported at 95 and 174 days. Litters consist of one or two cubs weighing about 280–325 g (9.9–11.5 oz) each.[5][19] Cubs are born blind and hairless. Initially, they are totally dependent on their mothers, and suckle for about 18 months. After one to three months, the young can run, play, and forage near their mothers. They reach sexual maturity after 3–4 years, and may live up to 30 years in captivity.[citation needed]

Threats

The two major threats to sun bears are habitat loss and commercial hunting. These threats are not evenly distributed throughout their range. In areas where deforestation is actively occurring, they are mainly threatened by the loss of forest habitat and forest degradation arising from clear-cutting for plantation development, unsustainable logging practices, illegal logging both within and outside protected areas, and forest fires.[1]The main predator of sun bears throughout its range by far is man. Commercial poaching of bears for the wildlife trade is a considerable threat in most countries. During surveys in Kalimantan between 1994 and 1997, interviewees admitted to hunting sun bears and indicated that sun bear meat is eaten by indigenous people in several areas in Kalimantan. High consumption of bear parts was reported to occur where Japanese or Korean expatriate employees of timber companies created a temporary demand. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) shops in Sarawak and Sabah offered sun bear gallbladders. Several confiscated sun bears indicated that live bears are also in demand for the pet trade.[20]

Sun bears are among the three primary bear species specifically targeted for the bear bile trade in Southeast Asia, and are kept in bear farms in Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar. Bear bile products include raw bile sold in vials, gall bladder by the gram or in whole form, flakes, powder and pills. The commercial production of bear bile from bear farming has turned bile from a purely traditional medicinal ingredient to a commodity with bile now found in non-TCM products like cough drops, shampoo, and soft drinks.[21]

Tigers and other large cats are potential predators.[22] American Museum of Natural History naturalist and co-founder Albert S. Bickmore described a case in which a tiger-sun bear interaction resulted in a prolonged altercation and in the death of both animals.[23] A wild female sun bear was swallowed by a large reticulated python in a lowland dipterocarp forest in East Kalimantan. The python possibly had come across the sleeping bear. Other predators on mainland Southeast Asia and Sumatra could be the leopard and the clouded leopard, although the latter could be too small to kill an adult sun bear.[24]

Conservation

Helarctos malayanus has been listed on CITES Appendix I since 1979. Killing of sun bears is strictly prohibited under national wildlife protection laws throughout their range. However, little enforcement of these laws occurs.[1]In captivity

The Malayan sun bear is part of an international captive-breeding program and has a Species Survival Plan under the Association of Zoos and Aquariums since late 1994.[19] Since that same year, the European breed registry for sun bears is kept in the Cologne Zoological Garden, Germany.[25]Comprehensive research about sun bear conservation and rehabilitation is the mission of the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre in Sandakan, Sabah, founded in 2008 by wildlife biologist Wong Siew Te.

Gallery

- Malayan sun bear at the Columbus Zoo

- A juvenile sun bear at the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre, Malaysia