The

great white shark (

Carcharodon carcharias), also known as the

great white,

white shark or "white pointer", is a species of large

mackerel shark

which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major

oceans. The great white shark is notable for its size, with larger

female individuals growing to 6.1 m (20 ft) in length and 1,905–2,268 kg

(4,200–5,000 lb) in weight at maturity.

[3][4][5] However, most are smaller; males measure 3.4 to 4.0 m (11 to 13 ft), and females measure 4.6 to 4.9 m (15 to 16 ft) on average.

[4][6]

According to a 2014 study, the lifespan of great white sharks is

estimated to be as long as 70 years or more, well above previous

estimates,

[7] making it one of the longest lived

cartilaginous fish currently known.

[8]

According to the same study, male great white sharks take 26 years to

reach sexual maturity, while the females take 33 years to be ready to

produce offspring.

[9] Great white sharks can swim at speeds of over 56 km/h (35 mph),

[10] and can swim to depths of 1,200 m (3,900 ft).

[11]

The great white shark has no known natural predators other than, on very rare occasions, the

killer whale.

[12] The great white shark is arguably the world's largest known extant macropredatory fish, and is one of the primary predators of

marine mammals, up to the size of large baleen whales. It is also known to prey upon a variety of other marine animals, including

fish, and

seabirds. It is the only known surviving

species of its

genus Carcharodon, and is responsible for more recorded human bite incidents than any other shark.

[13][14]

The species faces numerous ecological challenges which has resulted in international protection. The

IUCN lists the great white shark as a

vulnerable species,

[2] and it is included in

Appendix II of

CITES.

[15] It is also protected by several national governments such as Australia (as of 2018).

[16]

The novel

Jaws by

Peter Benchley and its subsequent

film adaptation by

Steven Spielberg depicted the great white shark as a "ferocious

man eater". Humans are not the preferred prey of the great white shark,

[17] but the great white is nevertheless responsible for the largest number of reported and identified fatal unprovoked

shark attacks on humans.

[18]

Taxonomy

The great white shark was one of the many

amphibia originally described by

Linnaeus in the landmark 1758

10th edition of his

Systema Naturae,

[19] its first scientific name,

Squalus carcharias. Later,

Sir Andrew Smith gave it

Carcharodon as its

generic name in 1833, and also in 1873. The generic name was identified with Linnaeus'

specific name and the current scientific name,

Carcharodon carcharias, was finalized.

Carcharodon comes from the

Ancient Greek words

κάρχαρος (

kárkharos, 'sharp' or 'jagged'), and

ὀδούς (

odoús),

ὀδών (

odṓn, 'tooth').

[20]

Ancestry and fossil record

The earliest known fossils of the great white shark are about 16 million years old, during the mid-

Miocene epoch.

[1][irrelevant citation] However, the

phylogeny

of the great white is still in dispute. The original hypothesis for the

great white's origins is that it shares a common ancestor with a

prehistoric shark, such as the

C. megalodon.

C. megalodon

had teeth that were superficially not too dissimilar with those of

great white sharks, but its teeth were far larger. Although

cartilaginous skeletons do not fossilize,

C. megalodon is

estimated to have been considerably larger than the great white shark,

estimated at up to 17 m (56 ft) and 59,413 kg (130,983 lb).

[21] Similarities among the physical remains and the extreme size of both the great white and

C. megalodon led many scientists to believe these sharks were closely related, and the name

Carcharodon megalodon was applied to the latter. However, a new hypothesis proposes that the

C. megalodon and the great white are distant relatives (albeit sharing the family

Lamnidae). The great white is also more closely related to an ancient

mako shark,

Isurus hastalis, than to the

C. megalodon,

a theory that seems to be supported with the discovery of a complete

set of jaws with 222 teeth and 45 vertebrae of the extinct

transitional species Carcharodon hubbelli in 1988 and published on 14 November 2012.

[22] In addition, the new hypothesis assigns

C. megalodon to the genus

Carcharocles, which also comprises the other megatoothed sharks;

Otodus obliquus is the ancient representative of the extinct

Carcharocles lineage.

[23]

Distribution and habitat

Great white sharks live in almost all coastal and offshore waters

which have water temperature between 12 and 24 °C (54 and 75 °F), with

greater concentrations in the

United States (

Northeast and

California),

South Africa,

Japan,

Oceania,

Chile, and the

Mediterranean including

Sea of Marmara and

Bosphorus.

[24][25] One of the densest known populations is found around

Dyer Island, South Africa.

[26]

The great white is an

epipelagic fish, observed mostly in the presence of rich game, such as

fur seals (

Arctocephalus ssp.),

sea lions,

cetaceans, other sharks, and large bony fish species. In the open ocean, it has been recorded at depths as great as 1,200 m (3,900 ft).

[11] These findings challenge the traditional notion that the great white is a coastal species.

[11]

According to a recent study,

California great whites have migrated to an area between

Baja California Peninsula and

Hawaii known as the

White Shark Café

to spend at least 100 days before migrating back to Baja. On the

journey out, they swim slowly and dive down to around 900 m (3,000 ft).

After they arrive, they change behavior and do short dives to about

300 m (980 ft) for up to ten minutes. Another white shark that was

tagged off the South African coast swam to the southern coast of

Australia and back within the year. A similar study tracked a different

great white shark from South Africa swimming to Australia's northwestern

coast and back, a journey of 20,000 km (12,000 mi; 11,000 nmi) in under

nine months.

[27]

These observations argue against traditional theories that white sharks

are coastal territorial predators, and open up the possibility of

interaction between shark populations that were previously thought to

have been discrete. The reasons for their migration and what they do at

their destination is still unknown. Possibilities include seasonal

feeding or mating.

[28]

In the Northwest Atlantic the white shark populations off the New England coast were nearly eradicated due to over-fishing.

[29] However, in recent years the populations have begun to grow greatly,

[30] largely due to the increase in seal populations on

Cape Cod,

Massachusetts since the enactment of the

Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972.

[31]

Currently very little is known about the hunting and movement patterns

of great whites off Cape Cod, but ongoing studies hope to offer insight

into this growing shark population.

[32]

A 2018 study indicated that white sharks prefer to congregate deep in

anticyclonic eddies in the

North Atlantic Ocean.

The sharks studied tended to favor the warm water eddies, spending the

daytime hours at 450 meters and coming to the surface at night.

[33]

Anatomy and appearance

Great white shark's skeleton

Great white shark near

Gansbaai, showing upper and lower teeth

The great white shark has a robust, large, conical snout. The upper and lower

lobes on the tail fin are approximately the same size which is similar to some

mackerel sharks. A great white displays

countershading,

by having a white underside and a grey dorsal area (sometimes in a

brown or blue shade) that gives an overall mottled appearance. The

coloration makes it difficult for prey to spot the shark because it

breaks up the shark's outline when seen from the side. From above, the

darker shade blends with the sea and from below it exposes a minimal

silhouette against the sunlight.

Leucism

is extremely rare in this species, but has been documented in one great

white shark (a pup that washed ashore in Australia and died).

[34] Great white sharks, like many other sharks, have rows of

serrated teeth

behind the main ones, ready to replace any that break off. When the

shark bites, it shakes its head side-to-side, helping the teeth saw off

large chunks of flesh.

[35]

Great white sharks, like other mackerel sharks, have larger eyes than

other shark species in proportion to their body size. The iris of the

eye is a deep blue instead of black.

[36]

Size

In great white sharks,

sexual dimorphism

is present, and females are generally larger than males. Male great

whites on average measure 3.4 to 4.0 m (11 to 13 ft) long, while females

at 4.6 to 4.9 m (15 to 16 ft).

[6] Adults of this species weigh 522–771 kg (1,151–1,700 lb) on average,

[39] however mature females can have an average mass of 680–1,110 kg (1,500–2,450 lb).

[4] The largest females have been verified up to 6.1 m (20 ft) in length and an estimated 1,905 kg (4,200 lb) in weight,

[3][4] perhaps up to 2,268 kg (5,000 lb).

[5]

The maximum size is subject to debate because some reports are rough

estimations or speculations performed under questionable circumstances.

[40] Among living

cartilaginous fish, only the

whale shark (

Rhincodon typus), the

basking shark (

Cetorhinus maximus) and the

giant manta ray (

Manta birostris),

in that order, are on average larger and heavier. These three species

are generally quite docile in disposition and given to passively

filter-feeding on very small organisms.

[39]

This makes the great white shark the largest extant macropredatory

fish. Great white sharks are at around 1.2 m (3.9 ft) when born, and

grow about 25 cm (9.8 in) each year.

[41]

According to J. E. Randall, the largest white shark reliably measured was a 6.0 m (19.7 ft) individual reported from

Ledge Point, Western Australia in 1987.

[42]

Another great white specimen of similar size has been verified by the

Canadian Shark Research Center: A female caught by David McKendrick of

Alberton,

Prince Edward Island, in August 1988 in the

Gulf of St. Lawrence off Prince Edward Island. This female great white was 6.1 m (20 ft) long.

[4]

However, there was a report considered reliable by some experts in the

past, of a larger great white shark specimen from Cuba in 1945.

[38][43][44][45] This specimen was reportedly 6.4 m (21 ft) long and had a body mass estimated at 3,324 kg (7,328 lb).

[38][44]

However, later studies also revealed that this particular specimen was

actually around 4.9 m (16 ft) in length, a specimen in the average

maximum size range.

[4]

The largest great white recognized by the

International Game Fish Association (IGFA) is one caught by Alf Dean in south Australian waters in 1959, weighing 1,208 kg (2,663 lb).

[40]

Several larger great whites caught by anglers have since been verified,

but were later disallowed from formal recognition by IGFA monitors for

rules violations.

Examples of large unconfirmed great whites

A number of very large unconfirmed great white shark specimens have been recorded.

[46] For decades, many

ichthyological works, as well as the

Guinness Book of World Records, listed two great white sharks as the largest individuals: In the 1870s, a 10.9 m (36 ft) great white captured in

southern Australian waters, near

Port Fairy, and an 11.3 m (37 ft) shark trapped in a

herring weir in

New Brunswick,

Canada,

in the 1930s. However, these measurements were not obtained in a

rigorous, scientifically valid manner, and researchers have questioned

the reliability of these measurements for a long time, noting they were

much larger than any other accurately reported sighting. Later studies

proved these doubts to be well founded. This New Brunswick shark may

have been a misidentified

basking shark,

as the two have similar body shapes. The question of the Port Fairy

shark was settled in the 1970s when J. E. Randall examined the shark's

jaws and "found that the Port Fairy shark was of the order of 5.0 m

(16.4 ft) in length and suggested that a mistake had been made in the

original record, in 1870, of the shark's length".

[42] These wrong measurements would make the alleged shark more than five times heavier than it really was.

While these measurements have not been confirmed, some great white

sharks caught in modern times have been estimated to be more than 7 m

(23 ft) long,

[47] but these claims have received some criticism.

[40][47] However, J. E. Randall believed that great white shark may have exceeded 6.1 m (20 ft) in length.

[42] A great white shark was captured near

Kangaroo Island in

Australia on 1 April 1987. This shark was estimated to be more than 6.9 m (23 ft) long by Peter Resiley,

[42][48] and has been designated as KANGA.

[47] Another great white shark was caught in

Malta

by Alfredo Cutajar on 16 April 1987. This shark was also estimated to

be around 7.13 m (23.4 ft) long by John Abela and has been designated as

MALTA.

[47]

However, Cappo drew criticism because he used shark size estimation

methods proposed by J. E. Randall to suggest that the KANGA specimen was

5.8–6.4 m (19–21 ft) long.

[47]

In a similar fashion, I. K. Fergusson also used shark size estimation

methods proposed by J. E. Randall to suggest that the MALTA specimen was

5.3–5.7 m (17–19 ft) long.

[47]

However, photographic evidence suggested that these specimens were

larger than the size estimations yielded through Randall's methods.

[47] Thus, a team of scientists—H. F. Mollet, G. M. Cailliet, A. P. Klimley, D. A. Ebert, A. D. Testi, and

L. J. V. Compagno—reviewed the cases of the KANGA and MALTA specimens in 1996 to resolve the dispute by conducting a comprehensive

morphometric

analysis of the remains of these sharks and re-examination of

photographic evidence in an attempt to validate the original size

estimations and their findings were consistent with them. The findings

indicated that estimations by P. Resiley and J. Abela are reasonable and

could not be ruled out.

[47]

A particularly large female great white nicknamed "Deep Blue",

estimated measuring at 6.1 m (20 ft) was filmed off Guadalupe during

shooting for the 2014 episode of

Shark Week

"Jaws Strikes Back". Deep Blue would also later gain significant

attention when she was filmed interacting with researcher Mauricio Hoyas

Pallida in a viral video that Mauricio posted on

Facebook on 11 June 2015.

[49]

Deep Blue was later seen off Oahu in January, 2019 while scavenging a

sperm whale carcass, whereupon she was filmed swimming beside divers

including dive tourism operator and model

Ocean Ramsey in open water.

[50][51][52] In July 2019, a fisherman, J. B. Currell, was on a trip to

Cape Cod from

Bermuda with Tom Brownell when they saw a large shark about 40 mi (64 km) southeast of

Martha's Vineyard.

Recording it on video, he said that it weighed about 5,000 lb

(2,300 kg), and measured 25–30 ft (7.6–9.1 m), evoking a comparison with

the fictional shark Jaws. The video was shared with the page "Troy

Dando Fishing" on Facebook.

[53][54] A particularly infamous great white shark, supposedly of record proportions, once patrolled the area that comprises

False Bay,

South Africa, was said to be well over 7 m (23 ft) during the early

1980s. This shark, known locally as the "Submarine", had a legendary

reputation that was supposedly well founded. Though rumors have stated

this shark was exaggerated in size or non-existent altogether, witness

accounts by the then young Craig Anthony Ferreira, a notable shark

expert in South Africa, and his father indicate an unusually large

animal of considerable size and power (though it remains uncertain just

how massive the shark was as it escaped capture each time it was

hooked). Ferreira describes the four encounters with the giant shark he

participated in with great detail in his book "Great White Sharks On

Their Best Behavior".

[55]

One contender in maximum size among the predatory sharks is the

tiger shark (

Galeocerdo cuvier).

While tiger sharks which are typically both a few feet smaller and have

a leaner, less heavy body structure than white sharks, have been

confirmed to reach at least 5.5 m (18 ft) in the length, an unverified

specimen was reported to have measured 7.4 m (24 ft) in length and

weighed 3,110 kg (6,860 lb), more than two times heavier than the

largest confirmed specimen at 1,524 kg (3,360 lb).

[39][56][57] Some other macropredatory sharks such as the

Greenland shark (

Somniosus microcephalus) and the

Pacific sleeper shark (

S. pacificus)

are also reported to rival these sharks in length (but probably weigh a

bit less since they are more slender in build than a great white) in

exceptional cases.

[58][59]

The question of maximum weight is complicated by the unresolved

question of whether or not to include the shark's stomach contents when

weighing the shark. With a single bite a great white can take in up to

14 kg (31 lb) of flesh and can also consume several hundred kilograms of

food.

Adaptations

A great white shark swimming

Great white sharks, like all other sharks, have an extra sense given by the

ampullae of Lorenzini

which enables them to detect the electromagnetic field emitted by the

movement of living animals. Great whites are so sensitive they can

detect variations of half a billionth of a

volt.

At close range, this allows the shark to locate even immobile animals

by detecting their heartbeat. Most fish have a less-developed but

similar sense using their body's

lateral line.

[60]

Shark biting into the fish head teaser bait next to a cage in

False Bay, South Africa

To more successfully hunt fast and agile prey such as sea lions, the

great white has adapted to maintain a body temperature warmer than the

surrounding water. One of these adaptations is a "

rete mirabile"

(Latin for "wonderful net"). This close web-like structure of veins and

arteries, located along each lateral side of the shark, conserves heat

by warming the cooler arterial blood with the venous blood that has been

warmed by the working muscles. This keeps certain parts of the body

(particularly the stomach) at temperatures up to 14 °C (25 °F)

[61]

above that of the surrounding water, while the heart and gills remain

at sea temperature. When conserving energy, the core body temperature

can drop to match the surroundings. A great white shark's success in

raising its

core temperature is an example of

gigantothermy. Therefore, the great white shark can be considered an

endothermic poikilotherm or

mesotherm because its body temperature is not constant but is internally regulated.

[35][62]

Great whites also rely on the fat and oils stored within their livers

for long-distance migrations across nutrient-poor areas of the oceans.

[63]

Studies by Stanford University and the Monterey Bay Aquarium published

on 17 July 2013 revealed that in addition to controlling the sharks'

buoyancy, the liver of great whites is essential in migration patterns.

Sharks that sink faster during drift dives were revealed to use up their

internal stores of energy quicker than those which sink in a dive at

more leisurely rates.

[64]

Toxicity from heavy metals seems to have little negative effects

on great white sharks. Blood samples taken from forty-three individuals

of varying size, age and sex off the South African coast led by

biologists from the University of Miami in 2012 indicates that despite

high levels of mercury, lead, and arsenic, there was no sign of raised

white blood cell count and granulate to lymphocyte ratios, indicating

the sharks had healthy immune systems. This discovery suggests a

previously unknown physiological defense against heavy metal poisoning.

Great whites are known to have a propensity for "self-healing and

avoiding age-related ailments".

[65]

Bite force

A 2007 study from the

University of New South Wales in

Sydney,

Australia, used

CT

scans of a shark's skull and computer models to measure the shark's

maximum bite force. The study reveals the forces and behaviors its skull

is adapted to handle and resolves competing theories about its feeding

behavior.

[66]

In 2008, a team of scientists led by Stephen Wroe conducted an

experiment to determine the great white shark's jaw power and findings

indicated that a specimen massing 3,324 kg (7,328 lb) could exert a bite

force of 18,216

newtons (4,095

lbf).

[44]

Ecology and behavior

A shark turns onto its back while hunting tuna

bait

This shark's behavior and social structure is complex.

[67] In South Africa, white sharks have a

dominance hierarchy

depending on the size, sex and squatter's rights: Females dominate

males, larger sharks dominate smaller sharks, and residents dominate

newcomers. When hunting, great whites tend to separate and resolve

conflicts with rituals and displays. White sharks rarely resort to

combat although some individuals have been found with bite marks that

match those of other white sharks. This suggests that when a great white

approaches too closely to another, they react with a warning bite.

Another possibility is that white sharks bite to show their dominance.

The great white shark is one of only a few sharks known to

regularly lift its head above the sea surface to gaze at other objects

such as prey. This is known as

spy-hopping. This behavior has also been seen in at least one group of

blacktip reef sharks,

but this might be learned from interaction with humans (it is theorized

that the shark may also be able to smell better this way because smell

travels through air faster than through water). White sharks are

generally very curious animals, display intelligence and may also turn

to socializing if the situation demands it. At Seal Island, white sharks

have been observed arriving and departing in stable "clans" of two to

six individuals on a yearly basis. Whether clan members are related is

unknown, but they get along peacefully enough. In fact, the social

structure of a clan is probably most aptly compared to that of a wolf

pack; in that each member has a clearly established rank and each clan

has an alpha leader. When members of different clans meet, they

establish social rank nonviolently through any of a variety of

interactions.

[68]

Diet

Great white sharks are

carnivorous and prey upon

fish (e.g.

tuna,

rays, other

sharks),

[68] cetaceans (i.e.,

dolphins,

porpoises,

whales),

pinnipeds (e.g.

seals,

fur seals,

[68] and

sea lions),

sea turtles,

[68] sea otters (

Enhydra lutris) and

seabirds.

[69]

Great whites have also been known to eat objects that they are unable

to digest. Juvenile white sharks predominantly prey on fish, including

other

elasmobranchs,

as their jaws are not strong enough to withstand the forces required to

attack larger prey such as pinnipeds and cetaceans until they reach a

length of 3 m (9.8 ft) or more, at which point their jaw cartilage

mineralizes enough to withstand the impact of biting into larger prey

species.

[70] Upon approaching a length of nearly 4 m (13 ft), great white sharks begin to target predominantly

marine mammals for food, though individual sharks seem to specialize in different types of prey depending on their preferences.

[71][72] They seem to be highly opportunistic.

[73][74]

These sharks prefer prey with a high content of energy-rich fat. Shark

expert Peter Klimley used a rod-and-reel rig and trolled carcasses of a

seal, a pig, and a sheep from his boat in the South

Farallons. The sharks attacked all three baits but rejected the sheep carcass.

[75]

Off California, sharks immobilize

northern elephant seals (

Mirounga angustirostris)

with a large bite to the hindquarters (which is the main source of the

seal's mobility) and wait for the seal to bleed to death. This technique

is especially used on adult male elephant seals, which are typically

larger than the shark, ranging between 1,500 and 2,000 kg (3,300 and

4,400 lb), and are potentially dangerous adversaries.

[76][77] Most commonly though, juvenile elephant seals are the most frequently eaten at elephant seal colonies.

[78] Prey is normally attacked sub-surface.

Harbor seals (

Phoca vitulina) are taken from the surface and dragged down until they stop struggling. They are then eaten near the bottom.

California sea lions (

Zalophus californianus) are ambushed from below and struck mid-body before being dragged and eaten.

[79]

In the Northwest Atlantic mature great whites are known to feed on both

harbor and

grey seals.

[31]

Unlike adults, juvenile white sharks in the area feed on smaller fish

species until they are large enough to prey on marine mammals such as

seals.

[80]

White sharks also attack dolphins and porpoises from above, behind or below to avoid being detected by their

echolocation. Targeted species include

dusky dolphins (

Lagenorhynchus obscurus),

[47] Risso's dolphins (

Grampus griseus),

[47] bottlenose dolphins (

Tursiops ssp.),

[47][81] Humpback dolphins (

Sousa ssp.),

[81] harbour porpoises (

Phocoena phocoena),

[47] and

Dall's porpoises (

Phocoenoides dalli).

[47] Groups of dolphins have occasionally been observed defending themselves from sharks with mobbing behaviour.

[81]

White shark predation on other species of small cetacean has also been

observed. In August 1989, a 1.8 m (5.9 ft) juvenile male

pygmy sperm whale (

Kogia breviceps) was found stranded in central California with a bite mark on its

caudal peduncle from a great white shark.

[82] In addition, white sharks attack and prey upon

beaked whales.

[47][81] Cases where an adult

Stejneger's beaked whale (

Mesoplodon stejnegeri), with a mean mass of around 1,100 kg (2,400 lb),

[83] and a juvenile

Cuvier's beaked whale (

Ziphius cavirostris), an individual estimated at 3 m (9.8 ft), were hunted and killed by great white sharks have also been observed.

[84]

When hunting sea turtles, they appear to simply bite through the

carapace around a flipper, immobilizing the turtle. The heaviest species

of bony fish, the

oceanic sunfish (

Mola mola), has been found in great white shark stomachs.

[73]

Off

Seal Island,

False Bay in South Africa, the sharks ambush

brown fur seals (

Arctocephalus pusillus)

from below at high speeds, hitting the seal mid-body. They can go so

fast that they completely leave the water. The peak burst speed is

estimated to be above 40 km/h (25 mph).

[85] They have also been observed chasing prey after a missed attack. Prey is usually attacked at the surface.

[86]

Shark attacks most often occur in the morning, within 2 hours of

sunrise, when visibility is poor. Their success rate is 55% in the first

2 hours, falling to 40% in late morning after which hunting stops.

[68]

A shark scavenging on a whale carcass in False Bay, South Africa

Whale carcasses comprise an important part of the diet of white

sharks. However, this has rarely been observed due to whales dying in

remote areas. It has been estimated that 30 kg (66 lb) of whale blubber

could feed a 4.5 m (15 ft) white shark for 1.5 months. Detailed

observations were made of four whale carcasses in False Bay between 2000

and 2010. Sharks were drawn to the carcass by chemical and odour

detection, spread by strong winds. After initially feeding on the whale

caudal peduncle and

fluke,

the sharks would investigate the carcass by slowly swimming around it

and mouthing several parts before selecting a blubber-rich area. During

feeding bouts of 15–20 seconds the sharks removed flesh with lateral

headshakes, without the protective ocular rotation they employ when

attacking live prey. The sharks were frequently observed regurgitating

chunks of blubber and immediately returning to feed, possibly in order

to replace low energy yield pieces with high energy yield pieces, using

their teeth as mechanoreceptors to distinguish them. After feeding for

several hours, the sharks appeared to become lethargic, no longer

swimming to the surface; they were observed mouthing the carcass but

apparently unable to bite hard enough to remove flesh, they would

instead bounce off and slowly sink. Up to eight sharks were observed

feeding simultaneously, bumping into each other without showing any

signs of aggression; on one occasion a shark accidentally bit the head

of a neighbouring shark, leaving two teeth embedded, but both continued

to feed unperturbed. Smaller individuals hovered around the carcass

eating chunks that drifted away. Unusually for the area, large numbers

of sharks over five metres long were observed, suggesting that the

largest sharks change their behaviour to search for whales as they lose

the maneuverability required to hunt seals. The investigating team

concluded that the importance of whale carcasses, particularly for the

largest white sharks, has been underestimated.

[87] In another documented incident, white sharks were observed scavenging on a whale carcass alongside tiger sharks.

[88] In 2020, Marine biologists Dines and Gennari

et al.,

published a documented incident in the journal "Marine and Freshwater

Research" of a group of great white sharks exhibiting pack-like

behavior, successfully attacking and killing a live adult humpback

whale. The sharks utilized the classic attack strategy utilized on

pinnipeds when attacking the whale, even utilizing the bite-and-spit

tactic they employ on smaller prey items. The incident is the first

known documentation of great whites actively killing a large baleen

whale.

[89]

Stomach contents of great whites also indicates that

whale sharks

both juvenile and adult may also be included on the animal's menu,

though whether this is active hunting or scavenging is not known at

present.

[90][91]

Reproduction

Great white sharks were previously thought to reach sexual maturity

at around 15 years of age, but are now believed to take far longer; male

great white sharks reach sexual maturity at age 26, while females take

33 years to reach sexual maturity.

[9][92][93] Maximum life span was originally believed to be more than 30 years, but a study by the

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

placed it at upwards of 70 years. Examinations of vertebral growth ring

count gave a maximum male age of 73 years and a maximum female age of

40 years for the specimens studied. The shark's late sexual maturity,

low reproductive rate, long gestation period of 11 months and slow

growth make it vulnerable to pressures such as overfishing and

environmental change.

[8]

Little is known about the great white shark's

mating

habits, and mating behavior has not yet been observed in this species.

It is possible that whale carcasses are an important location for

sexually mature sharks to meet for mating.

[87] Birth has never been observed, but pregnant females have been examined. Great white sharks are

ovoviviparous, which means eggs develop and hatch in the uterus and continue to develop until birth.

[94]

The great white has an 11-month gestation period. The shark pup's

powerful jaws begin to develop in the first month. The unborn sharks

participate in

oophagy, in which they feed on

ova produced by the mother. Delivery is in spring and summer.

[95]

The largest number of pups recorded for this species is 14 pups from a

single mother measuring 4.5 m (15 ft) that was killed incidentally off

Taiwan in 2019.

[96]

The Northern Pacific population of great whites is suspected to breed

off the Sea of Cortez, as evidenced by local fisherman who have said to

have caught them and evidenced by teeth found at dump sites for

discarded parts from their catches.

[citation needed]

Breaching behavior

A

breach

is the result of a high speed approach to the surface with the

resulting momentum taking the shark partially or completely clear of the

water. This is a hunting technique employed by great white sharks

whilst hunting seals. This technique is often used on cape fur seals at

Seal Island in

False Bay,

South Africa. Because the behavior is unpredictable, it is very hard to document. It was first photographed by

Chris Fallows and Rob Lawrence who developed the technique of towing a slow-moving seal decoy to trick the sharks to breach.

[97]

Between April and September, scientists may observe around 600

breaches. The seals swim on the surface and the great white sharks

launch their predatory attack from the deeper water below. They can

reach speeds of up to 40 km/h (25 mph) and can at times launch

themselves more than 3.0 m (10 ft) into the air. Just under half of

observed breach attacks are successful.

[98] In 2011, a 3 metres (9.8 ft) long shark jumped onto a seven-person

research vessel off Seal Island in Mossel Bay. The crew were undertaking a

population study using sardines as bait, and the incident was judged not to be an attack on the boat but an accident.

[99]

Natural threats

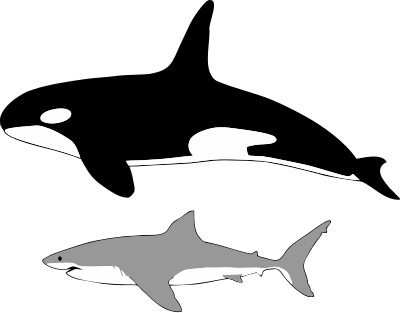

Comparison of the size of an average orca and an average great white shark

Interspecific competition between the great white shark and the

orca is probable in regions where dietary preferences of both species may overlap.

[81] An incident was documented on 4 October 1997, in the

Farallon Islands off

California

in the United States. An estimated 4.7–5.3 m (15–17 ft) female orca

immobilized an estimated 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft) great white shark.

[100] The orca held the shark upside down to induce

tonic immobility and kept the shark still for fifteen minutes, causing it to suffocate. The orca then proceeded to eat the dead shark's liver.

[81][100][101]

It is believed that the scent of the slain shark's carcass caused all

the great whites in the region to flee, forfeiting an opportunity for a

great seasonal feed.

[102] Another similar attack apparently occurred there in 2000, but its outcome is not clear.

[103] After both attacks, the local population of about 100 great whites vanished.

[101][103]

Following the 2000 incident, a great white with a satellite tag was

found to have immediately submerged to a depth of 500 m (1,600 ft) and

swum to

Hawaii.

[103] In 2015, a pod of orcas was recorded to have killed a great white shark off South Australia.

[104] In 2017, three great whites were found washed ashore near

Gaansbai, South Africa, with their body cavities torn open and the livers removed by what is likely to have been killer whales.

[105]

Killer whales also generally impact great white distribution. Studies

published in 2019 of killer whale and great white shark distribution and

interactions around the Farallon Islands indicate that the cetaceans

impact the sharks negatively, with brief appearances by killer whales

causing the sharks to seek out new feeding areas until the next season.

[106] Occasionally however, some great whites have been seen to swim near orcas without fear.

[107]

Conservation status

It is unclear how much of a concurrent increase in fishing for great

white sharks has caused the decline of great white shark populations

from the 1970s to the present. No accurate global population numbers are

available, but the great white shark is now considered vulnerable.

[2]

Sharks taken during the long interval between birth and sexual maturity

never reproduce, making population recovery and growth difficult.

The

IUCN

notes that very little is known about the actual status of the great

white shark, but as it appears uncommon compared to other widely

distributed species, it is considered

vulnerable.

[2] It is included in

Appendix II of

CITES,

[15] meaning that international trade in the species requires a permit.

[108] As of March 2010, it has also been included in Annex I of the

CMS Migratory Sharks MoU, which strives for increased international understanding and coordination for the protection of certain migratory sharks.

[109] A February 2010 study by

Barbara Block of

Stanford University

estimated the world population of great white sharks to be lower than

3,500 individuals, making the species more vulnerable to extinction than

the

tiger, whose population is in the same range.

[110] According to another study from 2014 by

George H. Burgess,

Florida Museum of Natural History,

University of Florida,

there are about 2,000 great white sharks near the California coast,

which is 10 times higher than the previous estimate of 219 by

Barbara Block.

[111][112]

Fishermen target many sharks for their jaws, teeth, and fins, and

as game fish in general. The great white shark, however, is rarely an

object of

commercial fishing, although its flesh is considered valuable. If casually captured (it happens for example in some

tonnare in the

Mediterranean), it is misleadingly sold as

smooth-hound shark.

[113]

In Australia

The great white shark was declared Vulnerable by the Australian

Government in 1999 because of significant population decline and is

currently protected under the

Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

[114] The causes of decline prior to protection included mortality from

sport fishing harvests as well as being caught in beach protection netting.

[115]

The national conservation status of the great white shark is

reflected by all Australian states under their respective laws, granting

the species full protection throughout Australia regardless of

jurisdiction.

[114]

Many states had prohibited the killing or possession of great white

sharks prior to national legislation coming into effect. The great white

shark is further listed as Threatened in

Victoria

under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act, and as rare or likely to

become extinct under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife Conservation Act in

Western Australia.

[114]

In 2002, the Australian government created the White Shark

Recovery Plan, implementing government-mandated conservation research

and monitoring for conservation in addition to federal protection and

stronger regulation of shark-related trade and tourism activities.

[115]

An updated recovery plan was published in 2013 to review progress,

research findings, and to implement further conservation actions.

[16] A study in 2012 revealed that Australia's White Shark population was separated by

Bass Strait into

genetically distinct eastern and western populations, indicating a need for the development of regional conservation strategies.

[116]

Presently, human-caused shark mortality is continuing, primarily

from accidental and illegal catching in commercial and recreational

fishing as well as from being caught in beach protection netting, and

the populations of great white shark in Australia are yet to recover.

[16]

In spite of official protections in Australia, great white sharks

continue to be killed in state "shark control" programs within

Australia. For example, the government of

Queensland has a "shark control" program (

shark culling) which kills great white sharks (as well as other marine life) using

shark nets and

drum lines with baited hooks.

[117][118] In Queensland, great white sharks that are found alive on the baited hooks are shot.

[119] The government of

New South Wales also kills great white sharks in its "shark control" program.

[118] Partly because of these programs, shark numbers in eastern Australia have decreased.

[120]

The Australasian population of great white sharks is believed to

be in excess of 8,000-10,000 individuals according to genetic research

studies done by

CSIRO,

with an adult population estimated to be around 2,210 individuals in

both Eastern and Western Australia. The annual survival rate for

juveniles in these two separate populations was estimated in the same

study to be close to 73 percent, while adult sharks had a 93 percent

annual survival rate. Whether or not mortality rates in great white

sharks have declined, or the population has increased as a result of the

protection of this species in Australian waters is as yet unknown due

to the slow growth rates of this species.

[121]

In New Zealand

As of April 2007, great white sharks were fully protected within

370 km (230 mi) of New Zealand and additionally from fishing by New

Zealand-flagged boats outside this range. The maximum penalty is a

$250,000 fine and up to six months in prison.

[122] In June 2018 the New Zealand

Department of Conservation classified the great white shark under the

New Zealand Threat Classification System

as "Nationally Endangered". The species meets the criteria for this

classification as there exists a moderate, stable population of between

1000 and 5000 mature individuals. This classification has the qualifiers

"Data Poor" and "Threatened Overseas".

[123]

In North America

In 2013, great white sharks were added to California's Endangered

Species Act. From data collected, the population of great whites in the

North Pacific was estimated to be fewer than 340 individuals. Research

also reveals these sharks are genetically distinct from other members of

their species elsewhere in Africa, Australia, and the east coast of

North America, having been isolated from other populations.

[124]

A 2014 study estimated the population of great white sharks along the California coastline to be approximately 2,400.

[125][126]

In 2015 Massachusetts banned catching, cage diving, feeding,

towing decoys, or baiting and chumming for its significant and highly

predictable migratory great white population without an appropriate

research permit. The goal of these restrictions is to both protect the

sharks and public health.

[127]

Relationship with humans

Shark bite incidents

Of all shark species, the great white shark is responsible for by far

the largest number of recorded shark bite incidents on humans, with 272

documented unprovoked bite incidents on humans as of 2012.

[18]

More than any documented bite incident,

Peter Benchley's best-selling novel

Jaws and the subsequent

1975 film adaptation directed by

Steven Spielberg provided the great white shark with the image of being a "

man eater" in the public mind.

[128]

While great white sharks have killed humans in at least 74 documented

unprovoked bite incidents, they typically do not target them: for

example, in the

Mediterranean Sea

there have been 31 confirmed bite incidents against humans in the last

two centuries, most of which were non-fatal. Many of the incidents

seemed to be "test-bites". Great white sharks also test-bite

buoys,

flotsam, and other unfamiliar objects, and they might grab a human or a

surfboard to identify what it is.

The

great white shark is one of only four kinds of shark that have been

involved in a significant number of fatal unprovoked attacks on humans.

Contrary to popular belief, great white sharks do not mistake humans for seals.

[129]

Many bite incidents occur in waters with low visibility or other

situations which impair the shark's senses. The species appears to not

like the taste of humans, or at least finds the taste unfamiliar.

Further research shows that they can tell in one bite whether or not the

object is worth predating upon. Humans, for the most part, are too bony

for their liking. They much prefer seals, which are fat and rich in

protein.

[130]

Humans are not appropriate prey because the shark's digestion is

too slow to cope with a human's high ratio of bone to muscle and fat.

Accordingly, in most recorded shark bite incidents, great whites broke

off contact after the first bite. Fatalities are usually caused by blood

loss from the initial bite rather than from critical organ loss or from

whole consumption. From 1990 to 2011 there have been a total of 139

unprovoked great white shark bite incidents, 29 of which were fatal.

[131]

However, some researchers have hypothesized that the reason the

proportion of fatalities is low is not because sharks do not like human

flesh, but because humans are often able to escape after the first bite.

In the 1980s, John McCosker, Chair of Aquatic Biology at the

California Academy of Sciences,

noted that divers who dove solo and were bitten by great whites were

generally at least partially consumed, while divers who followed the

buddy system were generally rescued by their companion. McCosker and

Timothy C. Tricas, an author and professor at the

University of Hawaii,

suggest that a standard pattern for great whites is to make an initial

devastating attack and then wait for the prey to weaken before consuming

the wounded animal. Humans' ability to move out of reach with the help

of others, thus foiling the attack, is unusual for a great white's prey.

[132]

Shark culling

Shark culling is the deliberate killing of sharks by a government in an attempt to reduce

shark attacks; shark culling is often called "shark control".

[118] These programs have been criticized by environmentalists and scientists — they say these programs harm the

marine ecosystem; they also say such programs are "outdated, cruel, and ineffective".

[133] Many different species (

dolphins,

turtles, etc.) are also killed in these programs (because of their use of

shark nets and

drum lines) — 15,135 marine animals were killed in New South Wales' nets between 1950 and 2008,

[118] and 84,000 marine animals were killed by Queensland authorities from 1962 to 2015.

[134]

Great white sharks are currently killed in both

Queensland and

New South Wales in "shark control" (shark culling) programs.

[118] Queensland uses

shark nets and

drum lines with baited hooks,

while New South Wales only uses nets. From 1962 to 2018, Queensland

authorities killed about 50,000 sharks, many of which were great whites.

[120] From 2013 to 2014 alone, 667 sharks were killed by Queensland authorities, including great white sharks.

[118] In Queensland, great white sharks found alive on the drum lines are shot.

[119] In New South Wales, between 1950 and 2008, a total of 577 great white sharks were killed in

nets.

[118] Between September 2017 and April 2018, 14 great white sharks were killed in New South Wales.

[135]

KwaZulu-Natal (an area of

South Africa)

also has a "shark control" program that kills great white sharks and

other marine life. In a 30-year period, more than 33,000 sharks were

killed in KwaZulu-Natal's shark-killing program, including great whites.

[136]

In 2014 the state government of

Western Australia led by Premier

Colin Barnett implemented a

policy of killing large sharks. The policy, colloquially referred to as the

Western Australian shark cull,

was intended to protect users of the marine environment from shark bite

incidents, following the deaths of seven people on the

Western Australian coastline in the years 2010–2013.

[137] Baited

drum lines were deployed near popular beaches using hooks designed to catch great white sharks, as well as

bull and

tiger sharks. Large sharks found hooked but still alive were shot and their bodies discarded at sea.

[138] The government claimed they were not

culling the sharks, but were using a "targeted, localised, hazard mitigation strategy".

[139] Barnett described opposition as "ludicrous" and "extreme", and said that nothing could change his mind.

[140]

This policy was met with widespread condemnation from the scientific

community, which showed that species responsible for bite incidents were

notoriously hard to identify, that the drum lines failed to capture

white sharks, as intended, and that the government also failed to show

any correlation between their drum line policy and a decrease in shark

bite incidents in the region.

[141]

Attacks on boats

Great white sharks infrequently bite and sometimes even sink boats.

Only five of the 108 authenticated unprovoked shark bite incidents

reported from the Pacific Coast during the 20th century involved

kayakers.

[142]

In a few cases they have bitten boats up to 10 m (33 ft) in length.

They have bumped or knocked people overboard, usually biting the boat

from the stern. In one case in 1936, a large shark leapt completely into

the

South African fishing boat

Lucky Jim,

knocking a crewman into the sea. Tricas and McCosker's underwater

observations suggest that sharks are attracted to boats by the

electrical fields they generate, which are picked up by the ampullae of

Lorenzini and confuse the shark about whether or not wounded prey might

be near-by.

[143]

In captivity

Prior to August 1981, no great white shark in captivity lived longer

than 11 days. In August 1981, a great white survived for 16 days at

SeaWorld San Diego before being released.

[144] The idea of containing a live great white at

SeaWorld Orlando was used in the 1983 film

Jaws 3-D.

Monterey Bay Aquarium first attempted to display a great white in 1984, but the shark died after 11 days because it did not eat.

[145] In July 2003, Monterey researchers captured a small female and kept it in a large netted pen near

Malibu for five days. They had the rare success of getting the shark to feed in captivity before its release.

[146]

Not until September 2004 was the aquarium able to place a great white

on long-term exhibit. A young female, which was caught off the coast of

Ventura,

was kept in the aquarium's 3,800,000 l (1,000,000 US gal) Outer Bay

exhibit for 198 days before she was released in March 2005. She was

tracked for 30 days after release.

[147] On the evening of 31 August 2006, the aquarium introduced a juvenile male caught outside

Santa Monica Bay.

[148] His first meal as a captive was a large

salmon

steak on 8 September 2006, and as of that date, he was estimated to be

1.72 m (68 in) in length and to weigh approximately 47 kg (104 lb). He

was released on 16 January 2007, after 137 days in captivity.

Monterey Bay Aquarium housed a third great white, a juvenile

male, for 162 days between 27 August 2007, and 5 February 2008. On

arrival, he was 1.4 m (4.6 ft) long and weighed 30.6 kg (67 lb). He grew

to 1.8 m (5.9 ft) and 64 kg (141 lb) before release. A juvenile female

came to the Outer Bay Exhibit on 27 August 2008. While she did swim

well, the shark fed only one time during her stay and was tagged and

released on 7 September 2008. Another juvenile female was captured near

Malibu on 12 August 2009, introduced to the Outer Bay exhibit on 26

August 2009, and was successfully released into the wild on 4 November

2009.

[149]

The Monterey Bay Aquarium added a 1.4 m (4.6 ft) long male into their

redesigned "Open Sea" exhibit on 31 August 2011. The animal was captured

in the waters off Malibu.

One of the largest adult great whites ever exhibited was at Japan's

Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium in 2016, where a 3.5 m (11 ft) male was exhibited for three days before dying.

[150][151]

Probably the most famous captive was a 2.4 m (7.9 ft) female named

Sandy, which in August 1980 became the only great white to be housed at

the

California Academy of Sciences'

Steinhart Aquarium in

San Francisco, California. She was released because she would not eat and constantly bumped against the walls.

[152]

Shark tourism

Cage diving is most common at sites where great whites are frequent including the coast of South Africa, the

Neptune Islands in South Australia,

[153] and

Guadalupe Island in

Baja California. The popularity of cage diving and swimming with sharks is at the focus of a booming tourist industry.

[154][155] A common practice is to

chum

the water with pieces of fish to attract the sharks. These practices

may make sharks more accustomed to people in their environment and to

associate human activity with food; a potentially dangerous situation.

By drawing bait on a wire towards the cage, tour operators lure the

shark to the cage, possibly striking it, exacerbating this problem.

Other operators draw the bait away from the cage, causing the shark to

swim past the divers.

At present, hang baits are illegal off Isla Guadalupe and

reputable dive operators do not use them. Operators in South Africa and

Australia continue to use hang baits and

pinniped decoys.

[156] In South Australia, playing rock music recordings underwater, including the

AC/DC album

Back in Black has also been used experimentally to attract sharks.

[157]

Companies object to being blamed for shark bite incidents, pointing out that

lightning tends to strike humans more often than sharks bite humans.

[158]

Their position is that further research needs to be done before banning

practices such as chumming, which may alter natural behavior.

[159]

One compromise is to only use chum in areas where whites actively

patrol anyway, well away from human leisure areas. Also, responsible

dive operators do not feed sharks. Only sharks that are willing to

scavenge follow the chum trail and if they find no food at the end then

the shark soon swims off and does not associate chum with a meal. It has

been suggested that government licensing strategies may help enforce

these responsible tourism.

[156]

The shark tourist industry has some financial leverage in

conserving this animal. A single set of great white jaws can fetch up to

£20,000. That is a fraction of the tourism value of a live shark;

tourism is a more sustainable economic activity than shark fishing. For

example, the dive industry in

Gansbaai,

South Africa consists of six boat operators with each boat guiding 30

people each day. With fees between £50 and £150 per person, a single

live shark that visits each boat can create anywhere between £9,000 and

£27,000 of revenue daily.

[citation needed]

-

A great white shark approaches divers in a cage off Dyer Island, Western Cape, South Africa.

A great white shark approaches a cage

-