Night monkeys, also known as owl monkeys or douroucoulis[2] (), are nocturnal New World monkeys of the genus Aotus, the only member of the family Aotidae ().

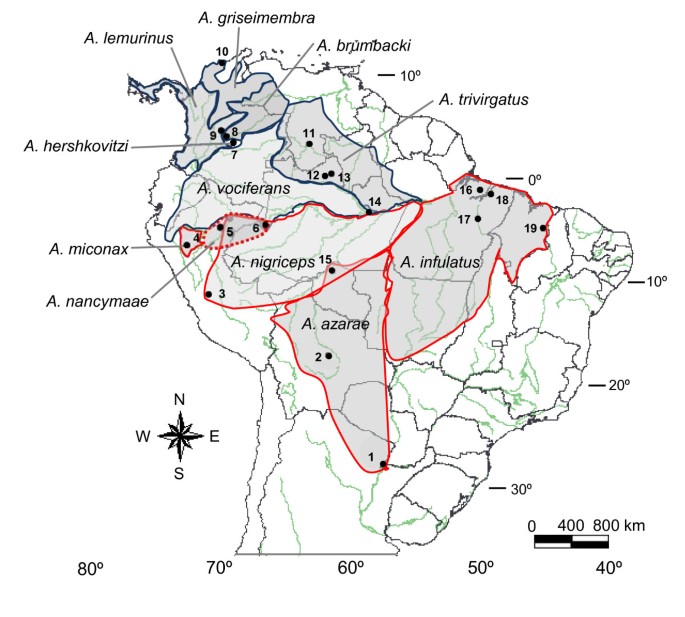

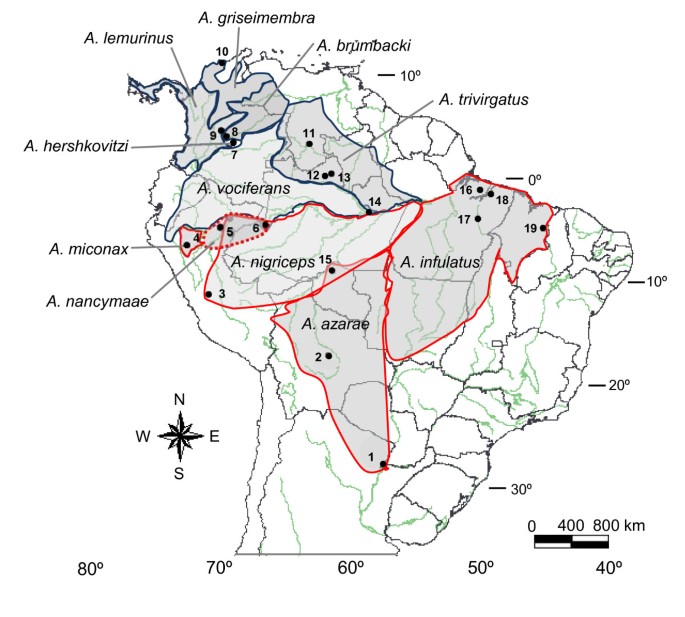

The genus comprises eleven species which are found across Panama and

much of South America in primary and secondary forests, tropical

rainforests and cloud forests up to 2,400 metres (7,900 ft). Night

monkeys have large eyes which improve their vision at night, while their

ears are mostly hidden, giving them their name Aotus, meaning "earless".

Night monkeys are the only truly nocturnal monkeys with the exception of some cathemeral populations of Azara's night monkey,

who have irregular bursts of activity during day and night. They have a

varied repertoire of vocalisations and live in small family groups of a

mated pair and their immature offspring. Night monkeys have monochromatic vision which improves their ability to detect visual cues at night.

Night monkeys are threatened by habitat loss, the pet trade, hunting for bushmeat, and by biomedical research. They constitute one of the few monkey species that are affected by the often deadly human malaria protozoan Plasmodium falciparum, making them useful as non-human primate experimental subjects in malaria research. The Peruvian night monkey is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as an Endangered species, while four are Vulnerable species, four are Least-concern species, and two are data deficient.

Taxonomy

Until 1983, all night monkeys were placed into only one (A. lemurimus) or two species (A. lemurinus and A. azarae).

Chromosome variability showed that there was more than one species in

the genus and Hershkovitz (1983) used morphological and karyological

evidence to propose nine species, one of which is now recognised as a junior synonym.[3] He split Aotus into two groups: a northern, gray-necked group (A. lemurinus, A. hershkovitzi, A. trivirgatus and A. vociferans) and a southern, red-necked group (A. miconax, A. nancymaae, A. nigriceps and A. azarae).[1] Arguably, the taxa otherwise considered subspecies of A. lemurinus – brumbacki, griseimembra and zonalis – should be considered separate species,[4][3] whereas A. hershkovitzi arguably is a junior synonym of A. lemurinus.[4] A new species from the gray-necked group was recently described as A. jorgehernandezi.[3] As is the case with some other splits in this genus,[5] an essential part of the argument for recognizing this new species was differences in the chromosomes.[3] Chromosome evidence has also been used as an argument for merging "species", as was the case for considering infulatus a subspecies of A. azarae rather than a separate species.[6] Fossil species have (correctly or incorrectly) been assigned to this genus, but only extant species are listed below.

Classification

Three-striped night monkey

Family Aotidae

- Genus Aotus

- Aotus lemurinus (gray-necked) group:

- Aotus azarae (red-necked) group:

Physical characteristics

Night

monkeys have large brown eyes; the size improves their nocturnal vision

increasing their ability to be active at night. They are sometimes said

to lack a tapetum lucidum, the reflective layer behind the retina possessed by many nocturnal animals.[7] Other sources say they have a tapetum lucidum composed of collagen fibrils.[8] At any rate, night monkeys lack the tapetum lucidum composed of riboflavin crystals possessed by lemurs and other strepsirrhines,[8] which is an indication that their nocturnalitiy is a secondary adaption evolved from ancestral diurnal primates.

Their ears are rather difficult to see; this is why their genus name, Aotus

(meaning "earless") was chosen. There is little data on the weights of

wild night monkeys. From the figures that have been collected, it

appears that males and females are similar in weight; the heaviest

species is Azara's night monkey at around 1,254 grams (2.765 lb), and the lightest is Brumback's night monkey,

which weighs between 455 and 875 grams (1.003 and 1.929 lb). The male

is slightly taller than the female, measuring 346 and 341 millimetres

(13.6 and 13.4 in), respectively.[9]

Ecology

Night monkeys can be found in Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Bolivia, and Venezuela.

The species that live at higher elevations tend to have thicker fur

than the monkeys at sea level. Night monkeys can live in forests

undisturbed by humans (primary forest) as well as in forests that are recovering from human logging efforts (secondary forest).[9]

Distribution

A primary distinction between red-necked and gray-necked night monkeys is spatial distribution. Gray-necked night monkeys (Aotus lemurinus group) are found north of the Amazon River, while the red-necked group (Aotus azare group) are localized south of the Amazon River.[10]

Red-necked night monkeys are found throughout various regions of the

Amazon rainforest of South America, with some variation occurring

between the four species. Nancy Ma's night monkey occurs in both flooded and unflooded tropical rainforest regions of Peru, preferring moist swamp and mountainous areas.[11] This species has been observed nesting in regions of the Andes[12] and has recently been introduced to Colombia, likely as a result of post-research release into the community.[13] The black-headed night monkey is also found mainly in the Peruvian Amazon (central and upper Amazon), however its range extends throughout Brazil and Bolivia[14] to the base of the Andes mountain chain.[15]

Night monkeys such like the black-headed night monkey, generally

inhabit cloud forests; areas with consistent presence of low clouds with

a high mist and moisture content which allows for lush and rich

vegetation to grow year round, providing excellent food and lodging

sources. The Peruvian night monkey,

like Nancy Ma's night monkey, is endemic to the Peruvian Andes however

it is found at a higher elevation, approximately 800–2,400 metres

(2,600–7,900 ft) above sea level and therefore exploits different niches

of this habitat.[15] The distribution of A. azare, extends further towards the Atlantic Ocean, spanning Argentina, Bolivia and the drier, south western regions of Paraguay,[16] however unlike the other red-necked night monkey species, it is not endemic to Brazil.

Sleep sites

During

the daylight hours, night monkeys rest in shaded tree areas. These

species have been observed exploiting four different types of tree

nests, monkeys will rest in; holes formed in the trunks of trees, in

concave sections of branches surrounded by creepers and epiphytes, in

dense areas of epiphyte, climber and vine growth and in areas of dense

foliage.[17]

These sleeping sites provide protection from environmental stressors

such as heavy rain, sunlight and heat. Sleeping sites are therefore

carefully chosen based upon tree age, density of trees, availability of

space for the group, ability of site to provide protection, ease of

access to the site and availability of site with respect to daily

routines.[17]

While night monkeys are an arboreal species, nests have not been

observed in higher strata of the rainforest ecosystem, rather a higher

density of nests were recorded at low-mid vegetation levels.[17]

Night monkeys represent a territorial species, territories are defended

by conspecifics through the use of threatening and agonistic

behaviours.[18]

Ranges between night monkey species often do overlap and result in

interspecific aggressions such as vocalizing and chasing which may last

up to an hour.[10]

Diet

Night monkeys

are primarily frugivorous (fruit eating species) as fruits are easily

distinguished through the use of olfactory cues,[19] but leaf and insect consumption has also been observed in the cathemeral night monkey species A. azare.[10]

A study conducted by Wolovich et al., indicated that juveniles and

females were much better at catching both crawling and flying insects

than adult males.[20]

In general, the technique used by night monkeys in insect capturing is

to use the palm of the hand to flatten a prey insect against a tree

branch and then proceed to consume the carcass.[20] During the winter months or when food sources are reduced, night monkeys have also been observed foraging on flowers such as Tabebuia heptaphylla, however this does not represent a primary food source.[10]

Reproduction

In

night monkeys, mating occurs infrequently, however females are fertile

year-round, with reproductive cycles range from 13 to 25 days.[21]

The gestation period for night monkey is approximately 117– 159 days

but varies from species to species. Birthing season extends from

September to March and is species dependant, with one offspring being

produced per year; however, in studies conducted in captivity, twins

were observed.[21]

Night monkeys reach puberty at a relatively young age, between 7– 11

months and most species attain full sexual maturity by the age of 2

years of age. A. azare represents an exception reaching sexual maturity by the age of 4.[21]

Behavior

The name "night monkey" comes from the fact that all species are active at night and are, in fact, the only truly nocturnal monkeys (an exception is the subspecies of Azara's night monkey, Aotus azarae azarae, which is cathemeral).[9]

Night monkeys make a notably wide variety of vocal sounds, with up to

eight categories of distinct calls (gruff grunts, resonant grunts,

sneeze grunts, screams, low trills, moans, gulps, and hoots), and a

frequency range of 190–1,950 Hz.[22] Unusual among the New World monkeys, they are monochromats,

that is, they have no colour vision, presumably because it is of no

advantage given their nocturnal habits. They have a better spatial

resolution at low light levels than other primates, which contributes to

their ability to capture insects and move at night.[23] Night monkeys live in family groups consisting of a mated pair and their immature offspring. Family groups defend territories by vocal calls and scent marking.

The night monkey is socially monogamous, and all night monkeys form pair bonds.

Only one infant is born each year. The male is the primary caregiver,

and the mother carries the infant for only the first week or so of its

life. This is believed to have developed because it increases the

survival of the infant and reduces the metabolic costs on the female.

Adults will occasionally be evicted from the group by same-sex

individuals, either kin or outsiders.[24]

Nocturnality

The family Aotidae

is the only family of nocturnal species within the suborder

Anthropoidea. While the order primates is divided into prosimians; many

of which are nocturnal, the anthropoids possess very few nocturnal

species and therefore it is highly likely that the ancestors of the

family Aotidae did not exhibit nocturnality and were rather diurnal species.[25] The presence of nocturnal behavior in Aotidae

therefore exemplifies a derived trait; an evolutionary adaptation that

conferred greater fitness advantages onto the night monkey.[25]

Night monkey share some similarities with nocturnal prosimians

including low basal metabolic rate, small body size and good ability to

detect visual cues at low light levels.[26]

Their responses to olfactory stimulus are intermediate between those of

the prosimians and diurnal primate species, however the ability to use

auditory cues remains more similar to diurnal primate species than to

nocturnal primate species.[26] This provides further evidence to support the hypothesis that nocturnality is a derived trait in the family Aotidae.

As the ancestor of Aotidae was likely diurnal, selective

and environmental pressures must have been exerted on the members of

this family which subsequently resulted in the alteration of their

circadian rhythm to adapt to fill empty niches.[25] Being active in the night rather than during the day time, gave Aotus

access to better food sources, provided protection from predators,

reduced interspecific competition and provided an escape from the harsh

environmental conditions of their habitat.[19] To begin, resting during the day allows for decreased interaction with diurnal predators. Members of the family Aotidae, apply the predation avoidance theory, choosing very strategic covered nests sites in trees.[27]

These primates carefully choose areas with sufficient foliage and vines

to provide cover from the sun and camouflage from predators, but which

simultaneously allow for visibility of ground predators and permit

effective routes of escape should a predator approach too quickly.[19][17]

Activity at night also permits night monkeys to avoid aggressive

interactions with other species such as competing for food and

territorial disputes; as they are active when most other species are

inactive and resting.[19]

Night monkeys also benefit from a nocturnal life style as

activity in the night provides a degree of protection from the heat of

the day and the thermoregulation difficulties associated.[27]

Although night monkey, like all primates are endothermic, meaning they

are able to produce their own heat, night monkeys undergo behavioural

thermoregulation in order to minimize energy expenditure.[27]

During the hottest points of the day, night monkeys are resting and

therefore expending less energy in the form of heat. As they carefully

construct their nests, night monkeys also benefit from the shade

provided by the forest canopy which enables them to cool their bodies

through the act of displacing themselves into a shady area.[27]

Additionally, finding food is energetically costly and completing this

process during the day time usually involves the usage of energy in the

form of calories and lipid reserves to cool the body down. Foraging

during the night when it is cooler, and when there is less competition,

supports the optimal foraging theory; maximize energy input while

minimizing energy output.[27]

While protection from predators, interspecific interactions, and

the harsh environment propose ultimate causes for nocturnal behavior as

they increase the species fitness, the proximate causes of nocturnality

are linked to the environmental effects on circadian rhythm.[28]

While diurnal species are stimulated by the appearance of the sun, in

nocturnal species, activity is highly impacted by the degree of moon

light available. The presence of a new moon has correlated with

inhibition of activity in night monkeys who exhibit lower levels of

activity with decreasing levels of moon light.[28] Therefore, the lunar cycle has a significant influence on the foraging and a nocturnal behaviors of night monkey species.[28]

Pair-bonded social animals (social monogamy)

Night

monkeys are socially monogamous—they form a bond and mate with one

partner. They live in small groups consisting of a pair of reproductive

adults, one infant and one to two juveniles.[29]

These species exhibit mate guarding, a practice in which the male

individual will protect the female he is bonded to and prevent other

conspecifics from attempting to mate with her.[30]

Mate guarding likely evolved as a means of reducing energy expenditure

when mating. As night monkey territories generally have some edge

overlap, there can be a large number of individuals coexisting in one

area which may make it difficult for a male to defend many females at

once due to high levels of interspecific competition for mates.[31] Night monkeys form bonded pairs and the energy expenditure of protecting a mate is reduced.[30]

Pair bonding may also be exhibited as a result of food distribution. In

the forest, pockets of food can be dense or very patchy and scarce.

Females, as they need energy stores to support reproduction are

generally distributed to areas with sufficient food sources.[32]

Males will therefore also have to distribute themselves to be within

proximity to females, this form of food distribution lends itself to

social monogamy as finding females may become difficult if males have to

constantly search for females which may be widely distributed depending

on food availability that year.[32]

However, while this does explain social monogamy, it does not

explain the high degree of paternal care which is exhibited by these

primates. After the birth of an infant, males are the primary carrier of

the infant, carrying offspring up to 90% of the time.[29]

In addition to aiding in child care, males will support females during

lactation through sharing their foraged food with lactating females.[33]

Generally, food sharing is not observed in nature as the search for

food requires a great degree of energy expenditure, but in the case of

night monkey males, food sharing confers offspring survival advantages.

As lactating females may be too weak to forage themselves, they may lose

the ability to nurse their child, food sharing therefore ensures that

offspring will be well feed.[33]

The act of food sharing is only observed among species where there is a

high degree of fidelity in paternity. Giving up valuable food sources

would not confer an evolutionary advance unless it increased an

individual's fitness; in this case, paternal care ensures success of

offspring and therefore increases the father's fitness.[33]

Olfactory communication and foraging

Recent

studies have proposed that night monkeys rely on olfaction and

olfactory cues for foraging and communication significantly more than

other diurnal primate species.[20]

This trend is reflected in the species physiology; members of Aotidae

possess larger scent perception organs than their diurnal counterparts.

The olfactory bulb, accessory olfactory bulb and volume of lateral

olfactory tract are all larger in Aotus than in any of the other new world monkey species.[34]

It is therefore likely that increased olfaction capacities improved the

fitness of these nocturnal primate species; they produced more

offspring and passed on these survival enhancing traits.[34]

The benefits of increased olfaction in night monkeys are twofold;

increased ability to use scent cues has facilitated night time foraging

and is also an important factor in mate selection and sexual

attractivity.[20]

As a substantial portion of the night monkey's activities

occurring during the dark hours of the night, there is a much lower

reliance of visual and tactile cues. When foraging at night, members of

the family Aotidae will smell fruits and leaves before ingesting to

determine the quality and safety of the food source. As they are highly

frugivorous and cannot perceive colour well, smell becomes the primary

determinant of the ripeness of fruits and is therefore an important

component in the optimal foraging methods of these primates.[34]

Upon finding a rich food source, night monkeys have been observed scent

marking not only the food source, but the route from their sleeping

site to the food source as well. Scent can therefore be used as an

effective method of navigation and reduce energy expenditure during

subsequent foraging expeditions.[34]

Night monkeys possess several scent glands covered by greasy hair

patches, which secrete pheromones that can be transferred onto

vegetation or other conspecifics. Scent glands are often located

subcaudal, but also occur near the muzzle and the sternum.[20]

The process of scent marking is accomplished through the rubbing of the

hairs covering scent glands onto the desired “marked item”.

Olfactory cues are also of significant importance in the process

of mating and mate guarding. Male night monkeys will rub subcaudal

glands onto their female partner in a process called “partner marking”

in order to relay the signal to coexisting males that the female is not

available for mating.[20]

Night monkeys also send chemical signals through urine to communicate

reproductive receptivity. In many cases, male night monkeys have been

observed drinking the urine of their female mate; it is proposed that

the pheromones in the urine can indicate the reproductive state of a

female and indicate ovulation.[20]

This is especially important in night monkeys as they cannot rely on

visual cues, such as the presence of a tumescence, to determine female

reproductive state.[20]

Therefore, olfactory communication in night monkeys is a result of

sexual selection; sexually dimorphic trait conferring increased

reproductive success. This trait demonstrates sexual dimorphism, as

males have larger subcaudal scent glands compare to female counterparts

and sex differences have been recorded in the glandular secretions of

each gender.[35]

There is a preference for scents of a particular type; those which

indicate reproductive receptivity, which increases species fitness by

facilitating the production of offspring.[35]

Conservation

According to the IUCN (the International Union for Conservation of Nature), the Peruvian night monkey is classified an Endangered species, four species are Vulnerable, four are Least-concern species,

and two are data deficient. Most night monkey species are threatened by

varying levels of habitat loss throughout their range, caused by agricultural expansion,

cattle ranching, logging, armed conflict, and mining operations. To

date, it is estimated that more than 62% of the habitat of the Peruvian night monkey has been destroyed or degraded by human activities.[12]

However, some night monkey species have become capable of adapting

exceptionally well to anthropogenic influences in their environment.

Populations of Peruvian night monkey have been observed thriving in

small forest fragments and plantation or farmland areas, however this is

likely possible given their small body size and may not be an

appropriate alternate habitat option for other larger night monkey

species.[12]

Studies have already been conducted into the feasibility of

agroforestry; plantations which simultaneously support local species

biodiversity.[36] In the case of A. miconax,

coffee plantations with introduced shade trees, provided quality

habitat spaces. While the coffee plantation benefited from the increased

shade—reducing weed growth and desiccation, night monkeys used the

space as a habitat, a connection corridor or stepping stone area between

habitats that provided a rich food source.[36]

However, some researchers question the agroforestry concept,

maintaining that monkeys are more susceptible to hunting, predator and

pathogens in plantation fields, thus indicating the need for further

research into the solution before implementation.[36]

Night monkeys are additionally threatened by both national and

international trade for bushmeat and domestic pets. Since 1975, the pet

trade of night monkeys has been regulated by CITES (the Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species). In the last forty years,

nearly 6,000 live night monkeys and more than 7,000 specimens have been

traded from the nine countries which they call home. While the

restrictive laws put into place by CITES are aiding in the reduction of

these numbers, 4 out of 9 countries, show deficiencies in maintaining

the standards outlined by CITES[13] Increased attention and enforcement of these laws will be imperative for the sustainability of night monkey populations.

Use in biomedical research poses another threat to night monkey biodiversity. Species such as Nancy Ma's night monkey, like human beings, are susceptible to infection by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite responsible for malaria.[37]

This trait caused them to be recommended by the World Health

Organization as test subjects in the development of malaria vaccines.[38]

Up to 2008, more than 76 night monkeys died as a result of vaccine

testing; some died from malaria, while others perished due to medical

complications from the testing.[39]

Increased research and knowledge of night monkey ecology is an

invaluable tool in determining conservation strategies for these species

and raising awareness for consequences of the anthropogenic threats

facing these primates. Radio-collaring of free ranging primates proposes

a method of obtaining more accurate and complete data surrounding

primate behavior patterns. This in turn can aid in understanding what

measures need to be taken to promote the conservation of these species.[40]

Radio collaring not only allows for the identification of individuals

within a species, increased sample size, more detailed dispersal and

range patterns, but also facilitates educational programs which raise

awareness for the current biodiversity crisis.[40]

The usage of radio-collaring while potentially extremely valuable, has

been shown to interfere with social group interactions, the development

of better collaring techniques and technology will therefore be

imperative in the realisation and successful use of radio collars on

night monkeys.[40]