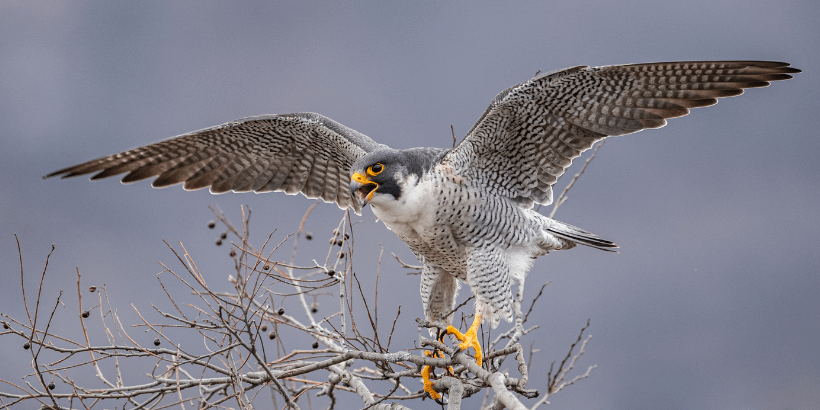

The peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), also known simply as the peregrine,[3] is a cosmopolitan bird of prey (raptor) in the family Falconidae. A large, crow-sized falcon, it has a blue-grey back, barred white underparts, and a black head. The peregrine is renowned for its speed. It can reach over 320 km/h (200 mph) during its characteristic hunting stoop (high-speed dive),[4] making it the fastest animal on the planet.[5][6][7] According to a National Geographic TV program, the highest measured speed of a peregrine falcon is 389 km/h (242 mph).[8][9] However, radar tracks have never confirmed this, the maximum speed reliably measured is 184 km/h, but nobody has been able to present unimpeachable measurements of speeds even close to the ‘well-known’ 300 km/h.[10] As is typical for bird-eating (avivore) raptors, peregrine falcons are sexually dimorphic, with females being considerably larger than males.[11][12] Historically, it has also been known as "black-cheeked falcon" in Australia,[13] and "duck hawk" in North America.[14]

The breeding range includes land regions from the Arctic tundra to the tropics. It can be found nearly everywhere on Earth, except extreme polar regions, very high mountains, and most tropical rainforests; the only major ice-free landmass from which it is entirely absent is New Zealand. This makes it the world's most widespread raptor[15] and one of the most widely found wild bird species. In fact, the only land-based bird species found over a larger geographic area owes its success to human-led introduction; the domestic and feral pigeons are both domesticated forms of the rock dove, a major prey species for Eurasian Peregrine populations. Due to their abundance over most other bird species in cities, feral pigeons support many peregrine populations as a staple food source, especially in urban settings.

The peregrine is a highly successful example of urban wildlife in much of its range, taking advantage of tall buildings as nest sites and an abundance of prey such as pigeons and ducks. Both the English and scientific names of this species mean "wandering falcon", referring to the migratory habits of many northern populations. A total of 18 or 19 regional subspecies are accepted, which vary in appearance; disagreement existed in the past over whether the distinctive Barbary falcon was represented by two subspecies of Falco peregrinus or was a separate species, F. pelegrinoides, and several of the other subspecies were originally described as species. The genetic differential between them (and also the difference in their appearance) is very small, only about 0.6–0.8% genetically differentiated, showing the divergence is relatively recent, during the time of the Last Ice Age;[16] all the major ornithological authorities now treat the barbary falcon as a subspecies.[17]

Although its diet consists almost exclusively of medium-sized birds, the peregrine will sometimes hunt small mammals, small reptiles, or even insects. Reaching sexual maturity at one year, it mates for life and nests in a scrape, normally on cliff edges or, in recent times, on tall human-made structures.[18] The peregrine falcon became an endangered species in many areas because of the widespread use of certain pesticides, especially DDT. Since the ban on DDT from the early 1970s, populations have recovered, supported by large-scale protection of nesting places and releases to the wild.[19]

The peregrine falcon is a well-respected falconry bird due to its strong hunting ability, high trainability, versatility, and availability via captive breeding. It is effective on most game bird species, from small to large. It has also been used as a religious, royal, or national symbol across multiple eras and areas of human civilization.

The peregrine falcon has a body length of 34 to 58 cm (13–23 in) and a wingspan from 74 to 120 cm (29–47 in).[11][20] The male and female have similar markings and plumage but, as with many birds of prey, the peregrine falcon displays marked sexual dimorphism in size, with the female measuring up to 30% larger than the male.[21] Males weigh 330 to 1,000 g (12–35 oz) and the noticeably larger females weigh 700 to 1,500 g (25–53 oz). In most subspecies, males weigh less than 700 g (25 oz) and females weigh more than 800 g (28 oz), and cases of females weighing about 50% more than their male breeding mates are not uncommon.[12][22][23] The standard linear measurements of peregrines are: the wing chord measures 26.5 to 39 cm (10.4–15.4 in), the tail measures 13 to 19 cm (5.1–7.5 in) and the tarsus measures 4.5 to 5.6 cm (1.8–2.2 in).[15]

The back and the long pointed wings of the adult are usually bluish black to slate grey with indistinct darker barring (see "Subspecies" below); the wingtips are black.[20] The white to rusty underparts are barred with thin clean bands of dark brown or black.[15] The tail, coloured like the back but with thin clean bars, is long, narrow, and rounded at the end with a black tip and a white band at the very end. The top of the head and a "moustache" along the cheeks are black, contrasting sharply with the pale sides of the neck and white throat.[24] The cere is yellow, as are the feet, and the beak and claws are black.[25] The upper beak is notched near the tip, an adaptation which enables falcons to kill prey by severing the spinal column at the neck.[11][12][4] An immature bird is much browner, with streaked, rather than barred, underparts, and has a pale bluish cere and orbital ring.[11]

A study shows that their black malar stripe exists to reduce glare from solar radiation, allowing them to see better. Photos from The Macaulay Library and iNaturalist showed that the malar stripe is thicker where there is more solar radiation.[26] That supports the solar glare hypothesis.

The peregrine falcon belongs to a genus whose lineage includes the hierofalcons[note 1] and the prairie falcon (F. mexicanus). This lineage probably diverged from other falcons towards the end of the Late Miocene or in the Late Pliocene, about 3–8 million years ago (mya).[16][29][30][31][32][33][34] As the peregrine-hierofalcon group includes both Old World and North American species, it is likely that the lineage originated in western Eurasia or Africa. Its relationship to other falcons is not clear, as the issue is complicated by widespread hybridization confounding mtDNA sequence analyses. One genetic lineage of the saker falcon (F. cherrug) is known[29][30] to have originated from a male saker ancestor producing fertile young with a female peregrine ancestor, and the descendants further breeding with sakers.[35]

Numerous subspecies of Falco peregrinus have been described, with 18 accepted by the IOC World Bird List,[36] and 19 accepted by the 1994 Handbook of the Birds of the World,[11][12][37] which considers the Barbary falcon of the Canary Islands and coastal North Africa to be two subspecies (F. p. pelegrinoides and F. p. babylonicus) of Falco peregrinus, rather than a distinct species, F. pelegrinoides. The following map shows the general ranges of these 19 subspecies.

The Barbary falcon is a subspecies of the peregrine falcon that inhabits parts of North Africa, from the Canary Islands to the Arabian Peninsula. There was discussion concerning the taxonomic status of the bird, with some considering it a subspecies of the peregrine falcon and others considering it a full species with two subspecies.[52]

Compared to the other peregrine falcon subspecies, Barbary falcons have a slimmer body[37] and a distinct plumage pattern. Despite numbers and range of these birds throughout the Canary Islands generally increasing, they are considered endangered, with human interference through falconry and shooting threatening their well-being. Falconry can further complicate the speciation and genetics of these Canary Islands falcons, as the practice promotes genetic mixing between individuals from outside the islands with those originating from the islands. Population density of the Barbary falcons on Tenerife, the biggest of the seven major Canary Islands, was found to be 1.27 pairs/100 km2, with the mean distance between pairs being 5869 ± 3338 m. The falcons were only observed near large and natural cliffs with a mean altitude of 697.6 m. Falcons show an affinity for tall cliffs away from human-mediated establishments and presence.

Barbary falcons have a red neck patch, but otherwise differ in appearance from the peregrine falcon proper merely according to Gloger's rule, relating pigmentation to environmental humidity.[53] The Barbary falcon has a peculiar way of flying, beating only the outer part of its wings as fulmars sometimes do; this also occurs in the peregrine falcon, but less often and far less pronounced.[12] The Barbary falcon's shoulder and pelvis bones are stout by comparison with the peregrine falcon and its feet are smaller.[37] Barbary falcons breed at different times of year than neighboring peregrine falcon subspecies,[12][29][30][32][37][54][55] but they are capable of interbreeding.[56] There is a 0.6–0.7% genetic distance in the peregrine falcon-Barbary falcon ("peregrinoid") complex.[32]

The peregrine falcon lives mostly along mountain ranges, river valleys, coastlines, and increasingly in cities.[15] In mild-winter regions, it is usually a permanent resident, and some individuals, especially adult males, will remain on the breeding territory. Only populations that breed in Arctic climates typically migrate great distances during the northern winter.[57]

The peregrine falcon reaches faster speeds than any other animal on the planet when performing the stoop,[5] which involves soaring to a great height and then diving steeply at speeds of over 320 km/h (200 mph), hitting one wing of its prey so as not to harm itself on impact.[4] The air pressure from such a dive could possibly damage a bird's lungs, but small bony tubercles on a falcon's nostrils are theorized to guide the powerful airflow away from the nostrils, enabling the bird to breathe more easily while diving by reducing the change in air pressure.[58] To protect their eyes, the falcons use their nictitating membranes (third eyelids) to spread tears and clear debris from their eyes while maintaining vision. The distinctive malar stripe or 'moustache', a dark area of feathers below the eyes, is thought to reduce solar glare and improve contrast sensitivity when targeting fast moving prey in bright light condition; the malar stripe has been found to be wider and more pronounced in regions of the world with greater solar radiation supporting this solar glare hypothesis.[59] Peregrine falcons have a flicker fusion frequency of 129 Hz (cycles per second), very fast for a bird of its size, and much faster than mammals.[60] A study testing the flight physics of an "ideal falcon" found a theoretical speed limit at 400 km/h (250 mph) for low-altitude flight and 625 km/h (388 mph) for high-altitude flight.[61] In 2005, Ken Franklin recorded a falcon stooping at a top speed of 389 km/h (242 mph).[8]

The life span of peregrine falcons in the wild is up to 19 years 9 months.[62] Mortality in the first year is 59–70%, declining to 25–32% annually in adults.[12] Apart from such anthropogenic threats as collision with human-made objects, the peregrine may be killed by larger hawks and owls.[63]

The peregrine falcon is host to a range of parasites and pathogens. It is a vector for Avipoxvirus, Newcastle disease virus, Falconid herpesvirus 1 (and possibly other Herpesviridae), and some mycoses and bacterial infections. Endoparasites include Plasmodium relictum (usually not causing malaria in the peregrine falcon), Strigeidae trematodes, Serratospiculum amaculata (nematode), and tapeworms. Known peregrine falcon ectoparasites are chewing lice,[note 5] Ceratophyllus garei (a flea), and Hippoboscidae flies (Icosta nigra, Ornithoctona erythrocephala).[20][64][65][66]

The peregrine falcon's diet varies greatly and is adapted to available prey in different regions. However, it typically feeds on medium-sized birds such as pigeons and doves, waterfowl, gamebirds, songbirds, parrots, seabirds, and waders.[25][67] Worldwide, it is estimated that between 1,500 and 2,000 bird species, or roughly a fifth of the world's bird species, are predated somewhere by these falcons. The peregrine falcon preys on the most diverse range of bird species of any raptor in North America, with over 300 species and including nearly 100 shorebirds.[68] Its prey can range from 3 g (0.11 oz) hummingbirds (Selasphorus and Archilochus ssp.) to the 3.1 kg (6.8 lb) sandhill crane, although most prey taken by peregrines weigh between 20 g (0.71 oz) (small passerines) and 1,100 g (2.4 lb) (ducks, geese, loons, gulls, capercaillies, ptarmigans and other grouse).[69][70][67][71] Smaller hawks (such as sharp-shinned hawks) and owls are regularly predated, as well as smaller falcons such as the American kestrel, merlin and, rarely, other peregrines.[72][73][67]

In urban areas, where it tends to nest on tall buildings or bridges, it subsists mostly on a variety of pigeons.[74] Among pigeons, the rock dove or feral pigeon comprises 80% or more of the dietary intake of peregrines. Other common city birds are also taken regularly, including mourning doves, common wood pigeons, common swifts, northern flickers, eurasian collared doves, common starlings, American robins, common blackbirds, and corvids such as magpies, jays or carrion, house, and American crows.[75][76] Coastal populations of the large subspecies pealei feed almost exclusively on seabirds.[24] In the Brazilian mangrove swamp of Cubatão, a wintering falcon of the subspecies tundrius was observed successfully hunting a juvenile scarlet ibis.[77]

Among mammalian prey species, bats in the genera Eptesicus, Myotis, Pipistrellus and Tadarida are the most common prey taken at night.[78] Though peregrines generally do not prefer terrestrial mammalian prey, in Rankin Inlet, peregrines largely take northern collared lemmings (Dicrostonyx groenlandicus) along with a few Arctic ground squirrels (Urocitellus parryii).[79] Other small mammals including shrews, mice, rats, voles, and squirrels are more seldom taken.[75][80] Peregrines occasionally take rabbits, mainly young individuals and juvenile hares.[80][81] Additionally, remains of red fox kits and adult female American marten were found among prey remains.[81] Insects and reptiles such as small snakes make up a small proportion of the diet, and salmonid fish have been taken by peregrines.[25][80][82]

The peregrine falcon hunts most often at dawn and dusk, when prey are most active, but also nocturnally in cities, particularly during migration periods when hunting at night may become prevalent. Nocturnal migrants taken by peregrines include species as diverse as yellow-billed cuckoo, black-necked grebe, virginia rail, and common quail.[75] The peregrine requires open space in order to hunt, and therefore often hunts over open water, marshes, valleys, fields, and tundra, searching for prey either from a high perch or from the air.[83] Large congregations of migrants, especially species that gather in the open like shorebirds, can be quite attractive to a hunting peregrine. Once prey is spotted, it begins its stoop, folding back the tail and wings, with feet tucked.[24] Prey is typically struck and captured in mid-air; the peregrine falcon strikes its prey with a clenched foot, stunning or killing it with the impact, then turns to catch it in mid-air.[83] If its prey is too heavy to carry, a peregrine will drop it to the ground and eat it there. If they miss the initial strike, peregrines will chase their prey in a twisting flight.[84]

Although previously thought rare, several cases of peregrines contour-hunting, i.e., using natural contours to surprise and ambush prey on the ground, have been reported and even rare cases of prey being pursued on foot. In addition, peregrines have been documented preying on chicks in nests, from birds such as kittiwakes.[85] Prey is plucked before consumption.[58] A 2016 study showed that the presence of peregrines benefits non-preferred species while at the same time causing a decline in its preferred prey.[86] As of 2018, the fastest recorded falcon was at 242 mph (nearly 390 km/h). Researchers at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and at Oxford University used 3D computer simulations in 2018 to show that the high speed allows peregrines to gain better maneuverability and precision in strikes.[87]

During the breeding season, the peregrine falcon is territorial; nesting pairs are usually more than 1 km (0.62 mi) apart, and often much farther, even in areas with large numbers of pairs.[88] The distance between nests ensures sufficient food supply for pairs and their chicks. Within a breeding territory, a pair may have several nesting ledges; the number used by a pair can vary from one or two up to seven in a 16-year period.

The peregrine falcon nests in a scrape, normally on cliff edges.[89] The female chooses a nest site, where she scrapes a shallow hollow in the loose soil, sand, gravel, or dead vegetation in which to lay eggs. No nest materials are added.[20] Cliff nests are generally located under an overhang, on ledges with vegetation. South-facing sites are favoured.[24] In some regions, as in parts of Australia and on the west coast of northern North America, large tree hollows are used for nesting. Before the demise of most European peregrines, a large population of peregrines in central and western Europe used the disused nests of other large birds.[25] In remote, undisturbed areas such as the Arctic, steep slopes and even low rocks and mounds may be used as nest sites. In many parts of its range, peregrines now also nest regularly on tall buildings or bridges; these human-made structures used for breeding closely resemble the natural cliff ledges that the peregrine prefers for its nesting locations.[11][88]

The pair defends the chosen nest site against other peregrines, and often against ravens, herons, and gulls, and if ground-nesting, also such mammals as foxes, wolverines, felids, bears, wolves, and mountain lions.[88] Both nests and (less frequently) adults are predated by larger-bodied raptorial birds like eagles, large owls, or gyrfalcons. The most serious predators of peregrine nests in North America and Europe are the great horned owl and the Eurasian eagle-owl. When reintroductions have been attempted for peregrines, the most serious impediments were these two species of owls routinely picking off nestlings, fledglings and adults by night.[90][91] Peregrines defending their nests have managed to kill raptors as large as golden eagles and bald eagles (both of which they normally avoid as potential predators) that have come too close to the nest by ambushing them in a full stoop.[92] In one instance, when a snowy owl killed a newly fledged peregrine, the larger owl was in turn killed by a stooping peregrine parent.[93]

The date of egg-laying varies according to locality, but is generally from February to March in the Northern Hemisphere, and from July to August in the Southern Hemisphere, although the Australian subspecies F. p. macropus may breed as late as November, and equatorial populations may nest anytime between June and December. If the eggs are lost early in the nesting season, the female usually lays another clutch, although this is extremely rare in the Arctic due to the short summer season. Generally three to four eggs, but sometimes as few as one or as many as five, are laid in the scrape.[94] The eggs are white to buff with red or brown markings.[94] They are incubated for 29 to 33 days, mainly by the female,[24] with the male also helping with the incubation of the eggs during the day, but only the female incubating them at night. The average number of young found in nests is 2.5, and the average number that fledge is about 1.5, due to the occasional production of infertile eggs and various natural losses of nestlings.[11][58][63]

After hatching, the chicks (called "eyases"[95]) are covered with creamy-white down and have disproportionately large feet.[88] The male (called the "tiercel") and the female (simply called the "falcon") both leave the nest to gather prey to feed the young.[58] The hunting territory of the parents can extend a radius of 19 to 24 km (12 to 15 mi) from the nest site.[96] Chicks fledge 42 to 46 days after hatching, and remain dependent on their parents for up to two months.[12]

Additionally the versatility of the species, with agility allowing capture of smaller birds and a strength and attacking style allowing capture of game much larger than themselves, combined with the wide size range of the many peregrine subspecies, means there is a subspecies suitable to almost any size and type of game bird. This size range, evolved to fit various environments and prey species, is from the larger females of the largest subspecies to the smaller males of the smallest subspecies, approximately five to one (approximately 1500 g to 300 g). The males of smaller and medium-sized subspecies, and the females of the smaller subspecies, excel in the taking of swift and agile small game birds such as dove, quail, and smaller ducks. The females of the larger subspecies are capable of taking large and powerful game birds such as the largest of duck species, pheasant, and grouse.

Peregrine falcons handled by falconers are also occasionally used to scare away birds at airports to reduce the risk of bird-plane strikes, improving air-traffic safety.[99] They were also used to intercept homing pigeons during World War II.[100]

Peregrine falcons have been successfully bred in captivity, both for falconry and for release into the wild.[101] Until 2004 nearly all peregrines used for falconry in the US were captive-bred from the progeny of falcons taken before the US Endangered Species Act was enacted and from those few infusions of wild genes available from Canada and special circumstances. Peregrine falcons were removed from the United States' endangered species list in 1999. The successful recovery program was aided by the effort and knowledge of falconers – in collaboration with The Peregrine Fund and state and federal agencies – through a technique called hacking. Finally, after years of close work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, a limited take of wild peregrines was allowed in 2004, the first wild peregrines taken specifically for falconry in over 30 years.

The development of captive breeding methods has led to peregrines being commercially available for falconry use, thus mostly eliminating the need to capture wild birds for support of falconry. The main reason for taking wild peregrines at this point is to maintain healthy genetic diversity in the breeding lines. Hybrids of peregrines and gyrfalcons are also available that can combine the best features of both species to create what many consider to be the ultimate falconry bird for the taking of larger game such as the sage-grouse. These hybrids combine the greater size, strength, and horizontal speed of the gyrfalcon with the natural propensity to stoop and greater warm weather tolerance of the peregrine.

Today, peregrines are regularly paired in captivity with other species such as the lanner falcon (F. biarmicus) to produce the "perilanner", a bird popular in falconry as it combines the peregrine's hunting skill with the lanner's hardiness, or the gyrfalcon to produce large, strikingly coloured birds for the use of falconers.

The peregrine falcon became an endangered species over much of its range because of the use of organochlorine pesticides, especially DDT, during the 1950s, '60s, and '70s.[19] Pesticide biomagnification caused organochlorine to build up in the falcons' fat tissues, reducing the amount of calcium in their eggshells. With thinner shells, fewer falcon eggs survived until hatching.[83][102] In addition, the PCB concentrations found in these falcons is dependent upon the age of the falcon. While high levels are still found in young birds (only a few months old) and even higher concentrations are found in more mature falcons, further increasing in adult peregrine falcons.[103] These pesticides caused falcon prey to also have thinner eggshells (one example of prey being the Black Petrels).[103] In several parts of the world, such as the eastern United States and Belgium, this species became locally extinct as a result.[12] An alternate point of view is that populations in the eastern North America had vanished due to hunting and egg collection.[39] Following the ban of organochlorine pesticides, the reproductive success of Peregrines increased in Scotland in terms of territory occupancy and breeding success, although spatial variation in recovery rates indicate that in some areas Peregrines were also impacted by other factors such as persecution.[104]

Peregrine falcon recovery teams breed the species in captivity.[105] The chicks are usually fed through a chute or with a hand puppet mimicking a peregrine's head, so they cannot see to imprint on the human trainers.[57] Then, when they are old enough, the rearing box is opened, allowing the bird to train its wings. As the fledgling gets stronger, feeding is reduced, forcing the bird to learn to hunt. This procedure is called hacking back to the wild.[106] To release a captive-bred falcon, the bird is placed in a special cage at the top of a tower or cliff ledge for some days or so, allowing it to acclimate itself to its future environment.[106]

Worldwide recovery efforts have been remarkably successful.[105] The widespread restriction of DDT use eventually allowed released birds to breed successfully.[57] The peregrine falcon was removed from the U.S. Endangered Species list on 25 August 1999.[57][107]

Some controversy has existed over the origins of captive breeding stock used by the Peregrine Fund in the recovery of peregrine falcons throughout the contiguous United States. Several peregrine subspecies were included in the breeding stock, including birds of Eurasian origin. Due to the local extinction of the eastern population of Falco peregrinus anatum, its near-extinction in the Midwest, and the limited gene pool within North American breeding stock, the inclusion of non-native subspecies was justified to optimize the genetic diversity found within the species as a whole.[108]

During the 1970s, peregrine falcons in Finland experienced a population bottleneck as a result of large declines associated with bio-accumulation of organochloride pesticides. However, the genetic diversity of peregrines in Finland is similar to other populations, indicating that high dispersal rates have maintained the genetic diversity of this species.[109]

Since peregrine falcon eggs and chicks are still often targeted by illegal poachers,[110] it is common practice not to publicise unprotected nest locations.[111]

Populations of the peregrine falcon have bounced back in most parts of the world. In the United Kingdom, there has been a recovery of populations since the crash of the 1960s. This has been greatly assisted by conservation and protection work led by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. The RSPB estimated that there were 1,402 breeding pairs in the UK in 2011.[112][113] In Canada, where peregrines were identified as endangered in 1978 (in the Yukon territory of northern Canada that year, only a single breeding pair was identified[114]), the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada declared the species no longer at risk in December 2017.[115]

Peregrines now breed in many mountainous and coastal areas, especially in the west and north, and nest in some urban areas, capitalising on the urban feral pigeon populations for food.[116] Additionally, falcons benefit from artificial illumination, which allows the raptors to extend their hunting periods into the dusk when natural illumination would otherwise be too low for them to pursue prey. In England, this has allowed them to prey on nocturnal migrants such as redwings, fieldfares, starlings, and woodcocks.[117]

In many parts of the world peregrine falcons have adapted to urban habitats, nesting on cathedrals, skyscraper window ledges, tower blocks,[118] and the towers of suspension bridges. Many of these nesting birds are encouraged, sometimes gathering media attention and often monitored by cameras.[119][note 6]

In England, peregrine falcons have become increasingly urban in distribution, particularly in southern areas where inland cliffs suitable as nesting sites are scarce. The first recorded urban breeding pair was observed nesting on the Swansea Guildhall in the 1980s.[117] In Southampton, a nest prevented restoration of mobile telephony services for several months in 2013, after Vodafone engineers despatched to repair a faulty transmitter mast discovered a nest in the mast, and were prevented by the Wildlife and Countryside Act – on pain of a possible prison sentence – from proceeding with repairs until the chicks fledged.[121]

In Oregon, Portland houses ten percent of the state's peregrine nests, despite only covering around 0.1 percent of the state's land area.[117]

Due to its striking hunting technique, the peregrine has often been associated with aggression and martial prowess. The Ancient Egyptian solar deity Ra was often represented as a man with the head of a peregrine falcon adorned with the solar disk, although most Egyptologists agree that it is most likely a Lanner falcon. Native Americans of the Mississippian culture (c. 800–1500) used the peregrine, along with several other birds of prey, in imagery as a symbol of "aerial (celestial) power" and buried men of high status in costumes associating to the ferocity of raptorial birds.[122] In the late Middle Ages, the Western European nobility that used peregrines for hunting, considered the bird associated with princes in formal hierarchies of birds of prey, just below the gyrfalcon associated with kings. It was considered "a royal bird, more armed by its courage than its claws". Terminology used by peregrine breeders also used the Old French term gentil, "of noble birth; aristocratic", particularly with the peregrine.[123]

Since 1927, the peregrine falcon has been the official mascot of Bowling Green State University in Bowling Green, Ohio.[124] The 2007 U.S. Idaho state quarter features a peregrine falcon.[125] The peregrine falcon has been designated the official city bird of Chicago.[126]

The Peregrine, by J. A. Baker,[127][128] is widely regarded as one of the best nature books in English written in the twentieth century. Admirers of the book include Robert Macfarlane,[129] Mark Cocker, who regards the book as "one of the most outstanding books on nature in the twentieth century"[130] and Werner Herzog, who called it "the one book I would ask you to read if you want to make films",[131] and said elsewhere "it has prose of the calibre that we have not seen since Joseph Conrad".[132] In the book, Baker recounts, in diary form, his detailed observations of peregrines (and their interaction with other birds) near his home in Chelmsford, Essex, over a single winter from October to April.

An episode of the hour-long TV series Starman in 1986 titled "Peregrine" was about an injured peregrine falcon and the endangered species program. It was filmed with the assistance of the University of California's peregrine falcon project in Santa Cruz.[133

Global range of F. peregrinus

Breeding summer visitor