The merlin (Falco columbarius) is a small species of falcon from the Northern Hemisphere,[2] with numerous subspecies throughout North America and Eurasia. A bird of prey, the merlin breeds in the northern Holarctic; some migrate to subtropical and northern tropical regions in winter. Males typically have wingspans of 53–58 centimetres (21–23 in), with females being slightly larger. They are swift fliers and skilled hunters which specialize in preying on small birds in the size range of sparrows to doves and medium-sized shorebirds. In recent decades merlin populations in North America have been significantly increasing, with some merlins becoming so well adapted to city life that they forgo migration; in Europe, populations increased up to about 2000 but have been steady subsequently.[3] The merlin has for centuries been well regarded as a falconry bird.

Merlin, nominate subspecies F. c. columbarius, in Prospect Park, New York

Merlin, nominate subspecies F. c. columbarius, in Prospect Park, New York

The merlin was described and illustrated by the English naturalist Mark Catesby (as the "pigeon hawk") in his Natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands published in 1729–1732.[4][5] Based on this description, in 1758 Carl Linnaeus included the species in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae and introduced the present binomial name Falco columbarius with the type locality as "America".[6] The genus name is Late Latin; falco derives from falx, falcis, a sickle, referring to the claws of the bird.[7] The species name columbarius is Latin for "of doves" from "columba", "dove".[8] Thirteen years after Linnaeus's description Marmaduke Tunstall recognized the Eurasian birds as a distinct taxon Falco aesalon in his Ornithologica Britannica. If two species of merlins are recognized, the Old World birds would thus bear the scientific name F. aesalon.[9][10]

The name "merlin" is derived from Old French esmerillon via Anglo-Norman merilun or meriliun. There are related Germanic words derived through older forms such as Middle Dutch smeerle, Old High German smerle and Old Icelandic smyrill.[11] Wycliffe's Bible, around 1382, mentions An Egle, & agriffyn, & a merlyon.[11] The species was once known as "pigeon hawk" in North America.[12]

European subspecies F. c. aesalon, Dumfries & Galloway, Scotland

The relationships of the merlin are not resolved to satisfaction. In size, shape and coloration, it is fairly distinct among living falcons. The red-necked falcon is sometimes considered more closely related to the merlin than other falcons, but this seems to be a coincidence due to similar hunting habits; it could not be confirmed in more recent studies. Indeed, the merlin seems to represent a lineage distinct from other living falcons since at least the Early Pliocene, some 5 Ma (million years ago). As suggested by biogeography and DNA sequence data, it might be part of an ancient non-monophyletic radiation of Falco species from Europe to North America, alongside the ancestors of forms such as the American kestrel (F. sparvierus), and the aplomado falcon (F. femoralis) and its relatives. A relationship with the red-necked falcon (F. chicquera) was once proposed based on their phenetic similarity, but this is not considered likely today.[9][10][14][15][16] More recently, a genetic link to two tropical African species, grey kestrel Falco ardosiaceus and dickinson's kestrel F. dickinsoni has been found.[17]

In that regard, a fossil falcon from the Early Blancan (4.3–4.8 Ma)[18] Rexroad Formation of Kansas. Known from an almost complete right coracoid (specimen UMMP V29107) and some tarsometatarsus, tibiotarsus and humerus pieces (V27159, V57508-V57510, V57513-V57514), this prehistoric falcon was slightly smaller than a merlin and apparently a bit more stout-footed, but otherwise quite similar. It was part of the Fox Canyon and Rexroad Local Faunas, and may have been the ancestor of the living merlins or its close relative. With its age quite certainly pre-dating the split between the Eurasian and North American merlins, the fossil falcon supports the idea of the merlin lineage originating in North America, or rather the colonization thereof. After adapting to its ecological niche, ancient merlins would have spread to Eurasia again, with gene flow being interrupted as the Beringia and Greenland regions became icebound in the Quaternary glaciation.[10][14][19]

That the merlin has a long-standing presence on both sides of the Atlantic is evidenced by the degree of genetic distinctness between Eurasian and North American populations. They are probably best considered distinct species, with gene flow having ceased at least a million years ago, but probably more;[10][17] but more study is required, particularly in the less-sampled subspecies, before a formal split can be made.[20]

By and large, color variation in either group independently follows Gloger's Rule. The Pacific temperate rain forest subspecies F. c. suckleyi males are almost uniformly black on the upperside and have heavy black blotches on the belly, whereas those of the lightest subspecies, F. c. pallidus, have little non-dilute melanin altogether, with gray upperside and reddish underside pattern.[9] Nine subspecies are currently accepted:[20]

- Northern Eurasia from British Isles through Scandinavia to central Siberia. Population of northern Britain shows evidence of gene flow from F. c. subaesalon. British Isles population resident or short-distance movement from moors to coasts, rest migratory; winters in Europe and the Mediterranean region to about Iran.

Juvenile, F. c. columbarius

The merlin is 24–33 cm (9.4–13.0 in) long with a 50–73 cm (20–29 in) wingspan.[22] Compared with most other small falcons, it is more robust and heavily built. Males average at about 165 g (5.8 oz) and females are typically about 230 g (8.1 oz). There is considerable variation, however, throughout the birds' range and—in particular in migratory populations—over the course of a year. Thus, adult males may weigh 125–210 g (4.4–7.4 oz), and females 190–300 g (6.7–10.6 oz). Each wing measures 18.2–23.8 cm (7.2–9.4 in), the tail measures 12.7–18.5 cm (5.0–7.3 in) and the tarsus measures 3.7 cm (1.5 in).[22][23] Such sexual dimorphism is common among raptors; it allows males and females to hunt different prey animals and decreases the territory size needed to feed a mated pair.[9][24]

The male merlin has a blue-gray back, ranging from almost black to silver-gray in different subspecies. Its underparts are buff- to orange-tinted and more or less heavily streaked with black to reddish brown. The female and immature are brownish-gray to dark brown above, and whitish buff spotted with brown below. Besides a weak whitish supercilium and the faint dark malar stripe—which are barely recognizable in both the palest and the darkest birds—the face of the merlin is less strongly patterned than in most other falcons. Nestlings are covered in pale buff down feathers, shading to whitish on the belly.[24]

The remiges are blackish, and the tail usually has some three to four wide, blackish bands, too. Very light males only have faint and narrow medium-gray bands, while in the darkest birds the bands are very wide, so that the tail appears to have narrow lighter bands instead. In all of them, however, the tail tip is black with a narrow white band at the very end, a pattern possibly plesiomorphic for all falcons. Altogether, the tail pattern is quite distinct though, resembling only that of the aplomado falcon (F. berigora) and (in light merlins) some typical kestrels. The eye and beak are dark, the latter with a yellow cere. The feet are also yellow, with black claws.[24]

Light American males may resemble the American kestrel (F. sparverius, not a typical kestrel), but merlin males have a gray back and tail rather than the reddish-brown of the kestrels. Light European males can be distinguished from kestrels by their mainly brown wings. In the north of South Asia, wintering males may be confused with the red-necked falcon (F. chicquera) if they fly away from the observer and the head (red on top in F. chicquera) and underside (finely barred with black in F. chicquera) are not visible.[24]

Merlins inhabit fairly open country, such as willow or birch scrub, shrubland, but also taiga forest, parks, grassland such as steppe and prairies, or moorland. They are not very habitat-specific and can be found from sea level to the treeline. In general, they prefer a mix of low and medium-height vegetation with some trees, and avoid dense forests as well as treeless arid regions. During migration however, they will utilize almost any habitat.[9]

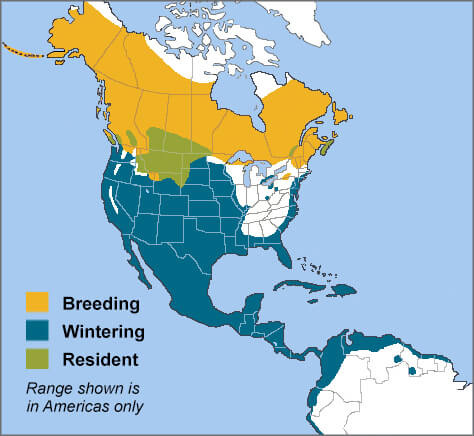

Most of its populations are migratory, wintering in warmer regions. Northern European birds move to southern Europe and North Africa, and North American populations to the southern United States to northern South America. In the milder maritime parts of its breeding range, such as Great Britain, the Pacific Northwest and western Iceland, as well as in Central Asia, it will merely desert higher ground and move to coasts and lowland during winter. The migration to the breeding grounds starts in late February, with most birds passing through the US, Central Europe and southern Russia in March and April, and the last stragglers arriving in the breeding range towards the end of May. Migration to winter quarters at least in Eurasia peaks in August/September, while e.g. in Ohio, just south of the breeding range, F. c. columbarius is typically recorded as a southbound migrant as late as September/October.[9][21] In Europe, merlins will roost communally in winter, often with hen harriers (Circus cyaneus). In North America, communal roosting is rare.

Merlins rely on speed and agility to hunt their prey. They often hunt by flying fast and low, typically less than 1 m (3.3 ft) above the ground, using trees and large shrubs to take prey by surprise. But they actually capture most prey in the air, and will "tail-chase" startled birds. Throughout its native range, the merlin is one of the most able aerial predators of small to mid-sized birds, more versatile if anything than the larger hobbies (which prefer to attack in mid-air) and the more nimble sparrowhawks (which usually go for birds resting or sleeping in dense growth). Breeding pairs will frequently hunt cooperatively, with one bird flushing the prey toward its mate.[9][25]

The merlin will readily take prey that is flushed by other causes, and can for example be seen tagging along sharp-shinned hawks (Accipiter striatus) to catch birds that escape from this ambush predator into the open air. It is quite unafraid, and will readily attack anything that moves conspicuously. Merlins have even been observed trying to "catch" automobiles and trains, and to feed on captive birds such as those snared in the mist nets used by ornithologists. Even under adverse conditions, one in 20 targets is usually caught, and under good conditions almost every other attack will be successful. Sometimes, merlins cache food to eat it later.[9][26]

In particular during the breeding season, most of the prey are smallish birds weighing 10–40 g (0.35–1.41 oz). Almost any such species will be taken, with local preferences for whatever is most abundant—be it larks (Alaudidae), pipits (Anthus), finches (Fringillidae),[27] house sparrows (Passer domesticus), other Old World sparrows (Passeridae), northern wheatears (Oenanthe oenanthe), thrushes (Turdus), kinglets (Regulidae)[28] or buntings (Emberiza)[27]—and inexperienced yearlings always a favorite. Smaller birds will generally avoid a hunting merlin if possible. In the Cayman Islands (where it only occurs in winter), bananaquits were noted to die of an apparent heart attack or stroke, without being physically harmed, when a merlin went at them and they could not escape.[26]

Larger birds (e.g. sandpipers, flickers,[29] other woodpeckers,[30] ptarmigan, other grouse,[27] ducks[31] and even rock doves[32] as heavy as the merlin itself) and other animals—insects (especially dragonflies, moths, grasshoppers, butterflies and beetles[33][34]), small mammals, (especially bats,[35] shrews,[36] rabbits,[33] voles, lemmings[37] and other small rodents[38]) reptiles (such as lizards and snakes)[27] and amphibians[39]—complement its diet. These are more important outside the breeding season, when they can make up a considerable part of the merlin's diet. But for example in Norway, while small birds are certainly the breeding merlin's staple food, exceptional breeding success seems to require an abundance of Microtus voles.[9]

Corvids are the primary threat to eggs and nestlings. Adult merlins may be preyed on by larger raptors, especially peregrine falcons (F. peregrinus), eagle-owls (e.g., great horned owl, Bubo virginianus), and larger Accipiter hawks (e.g., northern goshawk, A. gentilis). In general however, carnivorous birds avoid merlins due to their aggressiveness and agility. Their desire to drive larger raptors away from their territory is so pronounced that it is an identifying characteristic. Quoting from one popular raptor watching reference,[40] "An observer may use this aggressive tendency for identification purposes and as a means of detection. High-flying merlins often betray themselves and distinguish themselves because they are vigorously harassing another raptor (even ones as large as the Golden Eagle)."

Breeding occurs typically in May/June. Though the pairs are monogamous at least for a breeding season, extra-pair copulations have been recorded. Most nest sites have dense vegetative or rocky cover; the merlin does not build a proper nest of its own. Most will use abandoned corvid (particularly Corvus crow and Pica magpie) or hawk nests which are in conifer or mixed tree stands. In moorland—particularly in the UK—the female will usually make a shallow scrape in dense heather to use as a nest. Others nest in crevices on cliff-faces and on the ground, and some may even use buildings.[9]

Three to six (usually 4 or 5) eggs are laid. The rusty brown eggs average at about 40 mm × 31.5 mm (1.57 in × 1.24 in).[citation needed] The incubation period is 28 to 32 days. Incubation is performed by the female to about 90%; the male instead hunts to feed the family. Hatchlings weigh about 13 g (0.46 oz). The young fledge after another 30 days or so, and are dependent on their parents for up to 4 more weeks. Sometimes first-year merlins (especially males) will serve as a "nest helper" for an adult pair. More than half—often all or almost all—eggs of a clutch survive to hatching, and at least two-thirds of the hatched young fledge. However, as noted above, in years with little supplementary food only 1 young in 3 may survive to fledging. The merlin becomes sexually mature at one year of age and usually attempts to breed right away. The oldest wild bird known as of 2009 was recorded in its 13th winter.[9][41]

John James Audubon illustrated the merlin in the second edition of Birds of America (published in London, 1827–38) as Plate 75, under the title, "Le Petit Caporal – Falco temerarius". The image was engraved and colored by Robert Havell's London workshops. The original watercolor by Audubon was purchased by the New York History Society,[42] where it remains as of January 2009.

William Lewin illustrates the merlin as Plate 22 in volume 1 of his Birds of Great Britain and their Eggs, published 1789 in London.

In medieval Europe, merlins were popular in falconry: the Book of St. Albans listed it as "the falcon for a lady", where it was noted for classic "ringing" (circling rapidly upward) pursuits of the English skylark.[43] Though the merlin is only slightly larger than the American kestrel in dimensions, it averages about one third to one half larger by weight, with this weight mostly being extra muscle that gives it greater speed and endurance than the kestrel.[43] Like the American kestrel, the merlin offers the modern falconer the ability to hunt year round against sparrows and starlings, in urban settings not requiring large tracts of land or hunting dogs, with the additional advantage of being able to reliably take small game birds such as dove and quail during hunting season. A large and exceptionally aggressive female merlin may take prey

as large as pigeons and occasionally even small ducks.[44] They also offer an exciting style of flight, generally at closer range than large falcons where it may be more clearly witnessed and enjoyed by the falconer. In addition to horizontal tail-chases in the manner of American kestrels, they will also "ring up" in pursuit of prey that seeks to escape by out-climbing them, and perform high speed diving stoops on prey beneath them in the manner of larger falcons. Quoting from one popular falconry book on the eagerness of merlins to chase a swung lure, "Every stoop, outrun, dodge, and aerial maneuver of a hard flight to real quarry can be duplicated with no risk of loss of the falcon. Merlins regularly flown to the lure take most field quarries with such ease and such assurance as to make the field flight the less interesting and exciting of the two."[43]

By far the most serious long-term threat to these birds is habitat destruction, especially in their breeding areas. Ground-nesting populations in moorland have a preference for tall heather, and are thus susceptible to overmanagement by burning vast tracts instead of creating a habitat mosaic containing old and new growth. Still, the merlin is rather euryoecious (adaptable to various conditions) and will even live in settled areas, provided they have the proper mix of low and high vegetation, as well as sufficient prey (which is usually the case) and nesting sites (which is a common limiting factor).[9]

Perhaps the most frequent cause of accidental death for individuals is collision with man-made objects, particularly during attacks. This may account for almost half of all premature deaths of merlins. In the 1960s and 1970s, organochlorine pesticides were responsible for declines—particularly in Canada—due to eggshell thinning and subsequent brood failure, and compromising the immune system of adults. This has since been remedied with restrictions on the use of DDT and similar chemicals, and numbers have rebounded. Overall, merlin stocks appear globally stable; while they may decline temporarily in places, they will usually increase again eventually, suggesting that this phenomenon is due to the fluctuations of supplementary food stocks discussed above.[9]

Range of F. columbarius