The neotropical otter or neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) is a near-threatened (per the IUCN) otter species found in freshwater systems from Mexico and Central America through mainland South America, as well as the island of Trinidad. It is physically similar to the northern (L. canadensis) and southern river otter (L. provocax),

which occur directly north and south of this species' range,

respectively. Its head-to-body length can range from 36–66 centimetres

(14–26 in), plus a tail of 37–84 centimetres (15–33 in). Body weight

ranges from 5–15 kilograms (11–33 lb).[3]

At the Corrientes Zoo, Argentina

The neotropical otter is found in many different riverine habitats and riparian zones, including those in tropical and temperate deciduous to evergreen forests, savannas, llanos (of Colombia and Venezuela) and the pantanal (in Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay). It prefers to live in clear, fast-flowing rivers and streams, preferably away from competition with the more boisterous giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis).

Unlike other otters (including the aforementioned giant species), which

live in large and cohesive socio-familial units, the neotropical otter

is a relatively solitary animal, feeding mostly on fish and crustaceans.

The taxonomy of the genus Lontra has been debated, but the use of Lontra rather than Lutra

for New World otters is generally supported. The Neotropical otter has a

very wide range, covering a large portion of South America, so it is

not surprising there are geographical structures separating some

populations. One such geographical isolation is the Cordillera

Mountains. Additionally, the river in the Magdellena river valley flows

north, away from the mountains, decreasing the likelihood that otters in

the northern tip of South America will mix with otters elsewhere in the

continent.

Neotropical otters have an unusual phylogenic relationship to other otter species. They are most similar to marine otter (Lontra felina) and southern river otter (Lontra provocax),

which is not surprising considering these two species are found in

South America. However, Neotropical otters are relatively distantly

related to giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), which is surprising considering they have nearly identical ecological niches and home ranges.[4]

In one study, otters within a 1,600 sq mi (4,100 km2)

area in southern Brazil showed low nucleotide variation, but high

haplotype diversity compared to other otter species and other

carnivores. The study made the conclusion that otters may be undergoing a

recent increase in diversity. The results also show interrelatedness of

otters nearby and give reason to separate the species into subspecies:[5]

The Neotropical otter is covered in a short, dark grayish-brown pelage. Fur color is lighter around the muzzle and throat.[6] They possess a long wide tail, with short stout legs and fully webbed toes. Sexually dimorphic, the males are about 25% larger than the females.[7] Its head-and-body length can range from 36–66 centimetres (14–26 in), plus a tail of 37–84 centimetres (15–33 in).[3]

Body mass of the otter generally ranges from 5 to 15 kilograms (11–33

pounds). Neotropical otters will communicate with nearby otters via

scent marking. Communication may also occur via whistles, hums, and

screeches.[7]

The dental formula seldom varies from that of Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra), except in the few cases of otters that have dental anomalies.[8] Females and males have the same formula. The dental formula (for half the skull) is as follows:[9]

A neotropical otter in Bioparque Ukumarí, Colombia

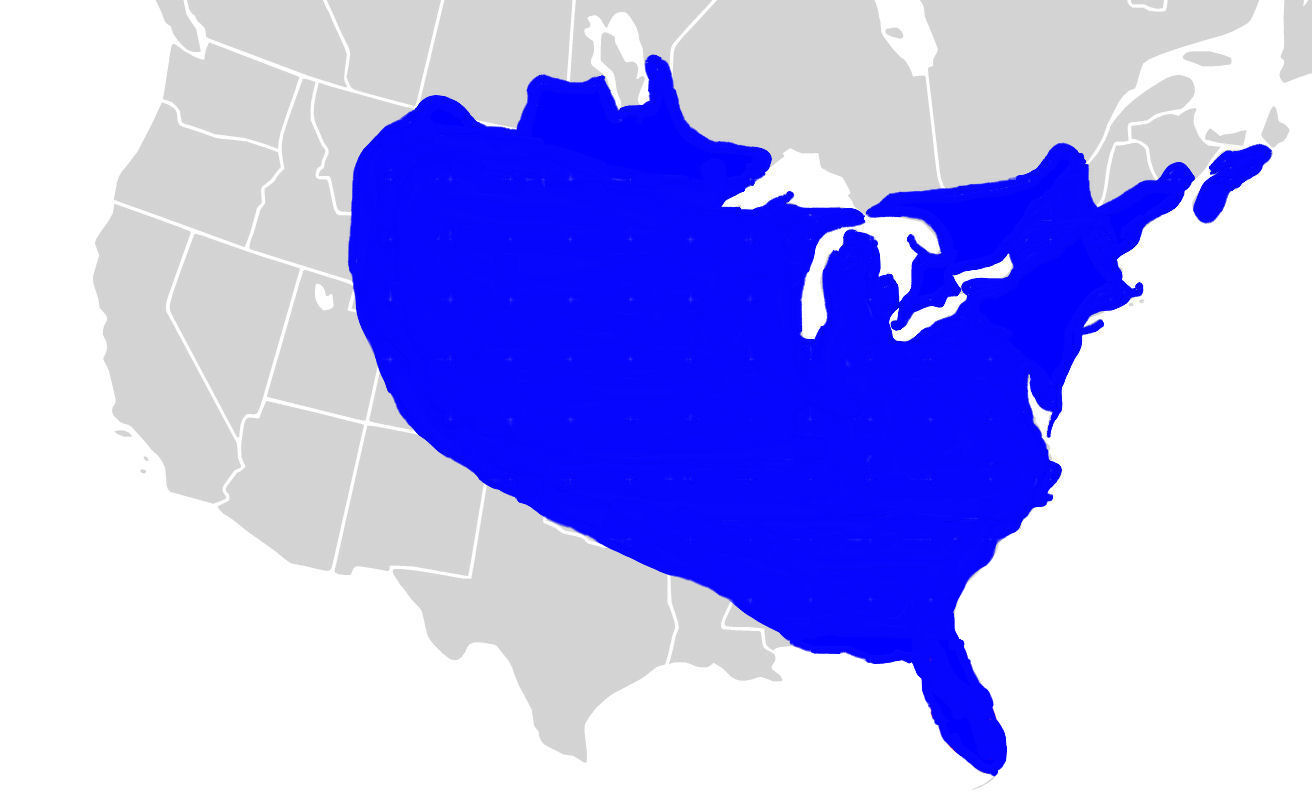

The Neotropical otter has the widest distribution of all the Lontra

species. Their habitat can range from northwest Mexico to central

Argentina. They prefer clear, fast-flowing rivers, and are rarely known

to settle in sluggish, silt-laden lowland waters or boggy areas. While

mostly occurring at 300–1,500 m (980–4,900 ft) above sea level, they

have been found settled at 3,000 m (9,800 ft).[10]

They require dense riparian vegetation and abundant den sites but,

other than that, the Neotropical otter is very versatile and tolerant to

environmental change. The otters prefer den sites that are solid, high,

dry, and in proximity to deep water.[11]

The Neotropical otter is the greatest generalist of all otter species.

In addition to rivers and streams, they can settle in and exploit some

rather formidable habitats, such as wastewater treatment plants, rice

paddies, sugar cane plantations, estuaries, deltas, drainage ditches,

and sometimes swamps. They can inhabit cold, glacial lakes and streams

in the Andes of Ecuador and Colombia.[12] Neotropical otters will also venture to the seashore and beaches (maintaining an almost "brackish" lifestyle), hunting marine creatures and playing in the highly saline water.[13]

The

Neotropical otter's diet consists mostly of fish and crustaceans making

up 67% and 28%, respectively, of its total diet. The otter will also

occasionally feed on mollusks and small mammals, as well as birds, large

insects and fruits.[14][15] In areas where fish and crustaceans are scarce, aquatic insects, such as dobsonfly larvae, can become its main prey.[16] This otter is known to occasionally attack fishnets for a source of prey, hindering fishing productivity.[13] Otters living near marine habitats can have a much higher proportion of crustaceans in their diets.

Seasonality also greatly affect otters' food choice. During the

dry season, when less fish and crustaceans are available, one study

found a higher proportion of frogs in otters' diet. Though, during this

time, anurans and reptiles still made up a very small percentage of the

total diet. This might also be due to the fact that certain frogs mate

during the dry season, so the frogs are easier prey. All in all, the

distribution of available food species in a particular area roughly

correlates to the percentage of each species found in otters' diet.[17]

Breeding occurs mostly in spring. Gestation will last 56 days and produce a litter of 1–5 pups.[6]

The pups are born blind yet fully furred. They will emerge from their

mother's nest when about 52 days and begin swimming at 74 days. They are

raised completely by their mother, as males do not provide any parental

care.[11]

The male will only spend a single day with the female during breeding

season. The female must keep her pups safe from predation by other

Neotropical otters. In one captive breeding situation, cannibalism by

the mother may have occurred, though it was not confirmed.[18]

In an ecologically healthy area, there are many possible shelters

so an individual can choose its preferred den. However, studies show

that not all possible shelters are occupied and not all shelters are

equally utilized by Neotropical otters. Otters visit different shelters

with varying frequencies, from once or few times per up to many times

per year. One factor that influences their preference for a den has to

do with the water level, especially during flood season, when a den near

water level can easily be washed away. A den may be at the water level,

near the bank, or more than 1.5 meters about the water level.[19]

There are many other factors influencing otters' preferences for a

shelter. Neotropical otters prefer dens near fresh water, high food

availability, and relatively deep and wide water. During seasons with

low water, individual otters may be more clumped because they will all

move into areas of a river with deeper water, with more fish.[19]

Deep, wide pools have been found to have a greater diversity of fish,

preferential for otters. Some studies show that otters will forgo a less

preferable, but more available den, like a muddy river bank, to spend

more time in a preferential den, like a rocky shore.[20]

Neotropical otter females will rear pups in a den without a male.

In some cases, a female may find a den that has space to keep her pups

and a separate area for her own space. A study of a male otter's

movement over 35 days showed he used three different dens without

communication between them. Also, this individual moved between two

islands separated by a one-kilometer wide estuary. He spent some time in

a site with heavy mud, poor substrate for a den, so he may have been on

the move to find food.

[21]

Dens may have more than one opening, so the otter can easily exit

to forage for food while staying safe from predators. There are many

classifications of dens that Neotropical otters may use. A cavity among

stones or under tree roots is preferred. In certain parts of South

America, an otter may come across a limestone dissolution cavity or a

cavity in a rocky wall. Though lacking a source of light, the

Neotropical otter can make great use of this sturdy home. As a last

resort, an otter expend energy to excavate a space among vegetation or a

river bank, though those homes are less sturdy. Vegetative cover is

also very important for the Neotropical otter. In comparison to other

otter dens, the Neotropical otter dens do not have holes directly into

the water, they do not use plant material as bedding, and will live in

caves without light. They are elusive creatures and prefer undisturbed

forests without signs of human activity. When humans clear forests for

agricultural land, the number of available otter habitats plummets.[19]

Like

other otter species, Neotropical otters will mark their territory with

scratching or spraint (feces) in obvious places like rocks and under

bridges.[22]

Signs of marking may be most concentrated around their dens. They tend

to only mark in certain areas of the den, separate from the activity

center of the den. In caves, where a water sources may leak through the

walls and wash away the scent, the resident may mark areas inside their

den.[19]

The

niches and ranges of the giant otter and the Neotropical otter overlap

widely. Both species are diurnal and mainly piscivorous. The giant otter

is less of a generalist in habitat, preferring slow-moving water and

overhanging vegetation, but where the Neotropical otter may also occur.

The giant otter is much larger and hunts in groups, so it can take

larger prey. Some areas, like the Pantanal, have high enough

productivity such that both otter species can coexist with little or no

competition (niche partitioning). Additionally, Neotropical otters prefer deeper and wider streams than giant otters.[12]

The Neotropical otter is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

The species is currently protected in Argentina and many other South

American countries. Heavy hunting for its fur in the 1950s–1970s

resulted in much local extinction over the otter's range. Illegal

hunting, habitat destruction through mining and ranching, and water

pollution still affect the population of the Neotropical otter.[23] Although there have been attempts at captive breeding, these attempts have been largely unsuccessful.[6]

Most negative feelings about otters arise from fishermen who

compete with the otter for fish. More data is needed to determine how

much overlap exists between the fishermen's desired catch and the

otter's diet. The highest competition between Neotropical otters and

fishermen occurs during drought conditions. Fishermen may move out of

their regular fishing areas, into deeper pools where the otter usually

hunts in the absence of people. In a study on local fishermen's

attitudes, the study revealed that fishermen's knowledge aligned with

scientific data about the Neotropical otter's behavior, body

description, and other data. Because the fishermen's facts aligned with

scientific knowledge, scientists could then trust the fishermen's

first-hand accounts about problems they experience with otters.

Fishermen reported that otters will damage their fishing gear, but do

not damage crab and shrimp nets. The locals have varying opinions about

the otters' presence, from understanding they have to share space with

the otters to wanting to kill the otters. There have been proposals to

subsidize their fish profits lost to otters. However, it might be more

beneficial to pay them to collect data on the species. This would

benefit fishermen economically, improve fishermen's attitude towards

them, and build on to currently insufficient data about this species.

Otters are rarely get caught in gillnets, and when they do they very

rarely die.[24]

Neotropical otters are threatened by habitat degradation associated with: agriculture, soil compaction, pollution, roadways, and runoff.

Also, when forests are cleared for cattle grazing, heavy vegetation

(which is the otter's preferred habitat) near streams is also cleared or

trampled by cattle. This species is a very important ecological

indicator because they prefer ecologically rich, aquatic habitats and

have a low reproductive potential.[20]

One male and one female Neotropical otter were captured near Caucasia, Colombia, and taken to Santa Fe Zoological Park

in 1994 and 1996, respectively. Zoo staff observed the pair mating in

the water, then separated the animals. The female had three births; one

was successful. The infant deaths may have been unintentionally caused

by the mother. One idea suggested the mother's enclosure was too small

and she had no access to water, as she would have had in the wild. The

mother's gestation period was 86 days for two separate breeding events

recorded at this zoo. An 86-day gestation period is much longer than the

previously accepted belief that gestation lasts around 60 days. Two

possible explanations are: differences might exist between different

subspecies or a later copulation may have occurred and not been

observed. Also, this otter species might display short-term variation in

gestation periods.[18]