The height of a full-grown, full-size llama is 1.7 to 1.8 m (5.6 to 5.9 ft) tall at the top of the head, and can weigh between 130 and 200 kg (290 and 440 lb). At birth, a baby llama (called a cria) can weigh between 9 and 14 kg (20 and 31 lb). Llamas typically live for 15 to 25 years, with some individuals surviving 30 years or more.[1][2][3]

They are very social animals and live with other llamas as a herd. The wool produced by a llama is very soft and lanolin-free. Llamas are intelligent and can learn simple tasks after a few repetitions. When using a pack, they can carry about 25 to 30% of their body weight for 8 to 13 km (5–8 miles).[4]

The name llama (in the past also spelled 'lama' or 'glama') was adopted by European settlers from native Peruvians.[5]

Llamas appear to have originated from the central plains of North America about 40 million years ago. They migrated to South America about three million years ago. By the end of the last ice age (10,000–12,000 years ago), camelids were extinct in North America.[4] As of 2007, there were over seven million llamas and alpacas in South America, and due to importation from South America in the late 20th century, there are now over 158,000 llamas and 100,000 alpacas in the United States and Canada.[6]

Classification

Lamoids, or llamas (as they are more generally known as a group), consist of the vicuña (Vicugna vicugna, prev. Lama vicugna), guanaco (Lama guanicoe), Suri alpaca, and Huacaya alpaca (Vicugna pacos, prev. Lama guanicoe pacos), and the domestic llama (Lama guanicoe glama). Guanacos and vicuñas live in the wild, while alpacas – as well as llamas – exist only as domesticated animals.[7]

Although early writers compared llamas to sheep, their similarity to

the camel was soon recognized. They were included in the genus Camelus along with alpaca in the Systema Naturae (1758) of Linnaeus.[8] They were, however, separated by Cuvier in 1800 under the name of lama along with the guanaco.[9] Alpacas and vicuñas are in genus Vicugna. The genera Lama and Vicugna are, with the two species of true camels, the sole existing representatives of a very distinct section of the Artiodactyla or even-toed ungulates, called Tylopoda,

or "bump-footed", from the peculiar bumps on the soles of their feet.

The Tylopoda consist of a single family, the Camelidae, and shares the order Artiodactyla with the Suina (pigs), the Tragulina (chevrotains), the Pecora (ruminants), and the Whippomorpha (hippos and cetaceans, which belong to Artiodactyla from a cladistic, if not traditional, standpoint). The Tylopoda have more or less affinity to each of the sister taxa,

standing in some respects in a middle position between them, sharing

some characteristics from each, but in others showing special

modifications not found in any of the other taxa.[citation needed]

A domestic llama

Characteristics

The following characteristics apply especially to llamas. Dentition of adults:-incisors 1/3 canines 1/1, premolars 2/2, molars 3/2; total 32. In the upper jaw, a compressed, sharp, pointed laniariform incisor near the hinder edge of the premaxilla is followed in the male at least by a moderate-sized, pointed, curved true canine in the anterior part of the maxilla.[12] The isolated canine-like premolar that follows in the camels is not present. The teeth of the molar series, which are in contact with each other, consist of two very small premolars (the first almost rudimentary) and three broad molars, constructed generally like those of Camelus. In the lower jaw, the three incisors are long, spatulate, and procumbent; the outer ones are the smallest. Next to these is a curved, suberect canine, followed after an interval by an isolated minute and often deciduous simple conical premolar; then a contiguous series of one premolar and three molars, which differ from those of Camelus in having a small accessory column at the anterior outer edge.

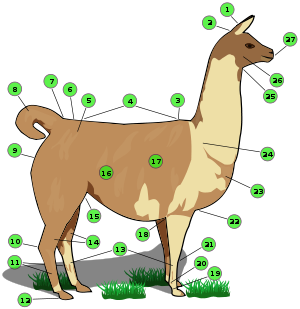

Names of llama body parts: 1 ears – 2 poll – 3 withers – 4 back – 5 hip – 6 croup – 7 base of tail – 8 tail – 9 buttock – 10 hock – 11 metatarsal gland – 12 heel – 13 cannon bone – 14 gaskin – 15 stifle joint – 16 flank – 17 barrel – 18 elbow – 19 pastern – 20 fetlock – 21 Knee – 22 Chest – 23 point of shoulder – 24 shoulder – 25 throat – 26 cheek or jowl – 27 muzzle

Vertebrae:

- cervical 7,

- dorsal 12,

- lumbar 7,

- sacral 4,

- caudal 15 to 20.

In essential structural characteristics, as well as in general appearance and habits, all the animals of this genus very closely resemble each other, so whether they should be considered as belonging to one, two, or more species is a matter of controversy among naturalists.

The question is complicated by the circumstance of the great majority of individuals that have come under observation being either in a completely or partially domesticated state. Many are also descended from ancestors that have previously been domesticated, a state that tends to produce a certain amount of variation from the original type. The four forms commonly distinguished by the inhabitants of South America are recognized as distinct species, though with difficulties in defining their distinctive characteristics.

These are:

- the llama, Lama glama (Linnaeus);

- the alpaca, Vicugna pacos (Linnaeus);

- the guanaco (from the Quechua huanaco), Lama guanicoe (Müller); and

- the vicuña, Vicugna vicugna (Molina)

Differential characteristics between llamas and alpacas include the llama's larger size, longer head, and curved ears. Alpaca fiber is generally more expensive, but not always more valuable. Alpacas tend to have a more consistent color throughout the body. The most apparent visual difference between llamas and camels is that camels have a hump or humps and llamas do not.

Reproduction

A dam and her cria

Like humans, llama males and females mature sexually at different rates. Females reach puberty at about 12 months old; males do not become sexually mature until around three years of age.[15]

Mating

Llamas mate with the female in a kush (lying down) position, which is fairly unusual in a large animal. They mate for an extended period of time (20–45 minutes), also unusual in a large animal.[16]Gestation

The gestation period of a llama is 11.5 months (350 days). Dams (female llamas) do not lick off their babies, as they have an attached tongue that does not reach outside of the mouth more than half an inch (1.3 cm). Rather, they will nuzzle and hum to their newborns.[17]

Crias

A cria (from Spanish for "baby") is the name for a baby llama, alpaca, vicuña, or guanaco. Crias are typically born with all the females of the herd gathering around, in an attempt to protect against the male llamas and potential predators. Llamas give birth standing. Birth is usually quick and problem-free, over in less than 30 minutes. Most births take place between 8 am and noon, during the warmer daylight hours. This may increase cria survival by reducing fatalities due to hypothermia during cold Andean nights. This birthing pattern is speculated to be a continuation of the birthing patterns observed in the wild. Crias are up and standing, walking and attempting to suckle within the first hour after birth.[18][19][20] Crias are partially fed with llama milk that is lower in fat and salt and higher in phosphorus and calcium than cow or goat milk. A female llama will only produce about 60 ml (2.1 imp fl oz) of milk at a time when she gives milk, so the cria must suckle frequently to receive the nutrients it requires.[21]

Breeding situations

In harem breeding, the male is left with females most of the year.

For field breeding, a female is turned out into a field with a male llama and left there for some period of time. This is the easiest method in terms of labor, but the least useful in terms of prediction of a likely birth date. An ultrasound test can be performed, and together with the exposure dates, a better idea of when the cria is expected can be determined.

Hand breeding is the most efficient method, but requires the most work on the part of the human involved. A male and female llama are put into the same pen and breeding is monitored. They are then separated and rebred every other day until one or the other refuses the breeding. Usually, one can get in two breedings using this method, though some studs have routinely refused to breed a female more than once. The separation presumably helps to keep the sperm count high for each breeding and also helps to keep the condition of the female llama's reproductive tract more sound. If the breeding is not successful within two to three weeks, the female is bred once again.

Pregnancy

Llamas at San Pedro de Atacama, Chile

- For "spit" testing, bring the potentially pregnant dam to an intact male. If the stud attempts to mate with her and she lies down for him within a fairly short period of time, she is not pregnant. If she remains on her feet, spits, attacks him, or otherwise prevents his being able to mate, it is assumed she is probably pregnant. This test gets its name due to the dam spitting at the male if she is pregnant.

- For progesterone testing, a veterinarian can test a blood sample for progesterone. A high level can indicate a pregnancy.

- With palpation, the veterinarian or breeder manually feels inside the llama to detect a pregnancy. Some risks to the llama exist, but it can be an accurate method for pregnancy detection.

- Ultrasound is the most accurate method for an experienced veterinarian, who can do an exterior examination and detect a fetus as early as 45 days.

Nutrition

Options for feeding llamas are quite wide; a wide variety of commercial and farm-based feeds are available. The major determining factors include feed cost, availability, nutrient balance and energy density required. Young, actively growing llamas require a greater concentration of nutrients than mature animals because of their smaller digestive tract capacities.[22]

Behavior

A pack llama in the Rocky Mountain National Park

When correctly reared, llamas spitting at a human is a rare thing. Llamas are very social herd animals, however, and do sometimes spit at each other as a way of disciplining lower-ranked llamas in the herd. A llama's social rank in a herd is never static. They can always move up or down in the social ladder by picking small fights. This is usually done between males to see which will become dominant. Their fights are visually dramatic, with spitting, ramming each other with their chests, neck wrestling and kicking, mainly to knock the other off balance. The females are usually only seen spitting as a means of controlling other herd members.

While the social structure might always be changing, they live as a family and they do take care of each other. If one notices a strange noise or feels threatened, a warning bray is sent out and all others become alert. They will often hum to each other as a form of communication.

The sound of the llama making groaning noises or going "mwa" is often a sign of fear or anger. If a llama is agitated, it will lay its ears back. One may determine how agitated the llama is by the materials in the spit. The more irritated the llama is, the further back into each of the three stomach compartments it will try to draw materials from for its spit.

An "orgle" is the mating sound of a llama or alpaca, made by the sexually aroused male. The sound is reminiscent of gargling, but with a more forceful, buzzing edge. Males begin the sound when they become aroused and continue throughout the act of procreation – from 15 minutes to more than an hour.[24][25]

Guard behavior

Main article: Guard llama

Llama guarding sheep on the South Downs in West Sussex

Research suggests the use of multiple guard llamas is not as effective as one. Multiple males tend to bond with one another, rather than with the livestock, and may ignore the flock. A gelded male of two years of age bonds closely with its new charges and is instinctively very effective in preventing predation. Some llamas appear to bond more quickly to sheep or goats if they are introduced just prior to lambing. Many sheep and goat producers indicate a special bond quickly develops between lambs and their guard llama and the llama is particularly protective of the lambs.

Using llamas as guards has reduced the losses to predators for many producers. The value of the livestock saved each year more than exceeds the purchase cost and annual maintenance of a llama. Although not every llama is suited to the job, most are a viable, nonlethal alternative for reducing predation, requiring no training and little care.[28]

History

According to Juan Ignacio Molina, the Dutch captain Joris van Spilbergen observed the use of chilihueques (possibly a llama type) by native Mapuches of Mocha Island as plow animals in 1614.[37]

Fiber

Llamas have a fine undercoat, which can be used for handicrafts and garments. The coarser outer guard hair is used for rugs, wall-hangings and lead ropes. The fiber comes in many different colors ranging from white or grey to reddish-brown, brown, dark brown and black.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.