Emus are soft-feathered, brown, flightless birds with long necks and legs, and can reach up to 1.9 metres (6.2 ft) in height. Emus can travel great distances, and when necessary can sprint at 50 km/h (31 mph); they forage for a variety of plants and insects, but have been known to go for weeks without eating. They drink infrequently, but take in copious amounts of water when the opportunity arises.

Breeding takes place in May and June, and fighting among females for a mate is common. Females can mate several times and lay several clutches of eggs in one season. The male does the incubation; during this process he hardly eats or drinks and loses a significant amount of weight. The eggs hatch after around eight weeks, and the young are nurtured by their fathers. They reach full size after around six months, but can remain as a family unit until the next breeding season. The emu is an important cultural icon of Australia, appearing on the coat of arms and various coins. The bird features prominently in Indigenous Australian mythology.

Taxonomy

History

Emus were first reported as having been seen by Europeans when explorers visited the western coast of Australia in 1696; this was an expedition led by Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh who was searching for survivors of a ship that had gone missing two years earlier.[6] The birds were known on the eastern coast before 1788, when the first Europeans settled there.[7] The birds were first mentioned under the name of the "New Holland cassowary" in Arthur Phillip's Voyage to Botany Bay, published in 1789 with the following description:[8][9]

This is a species differing in many particulars from that generally known, and is a much larger bird, standing higher on its legs and having the neck longer than in the common one. Total length seven feet two inches. The bill is not greatly different from that of the common Cassowary; but the horny appendage, or helmet on top of the head, in this species is totally wanting: the whole of the head and neck is also covered with feathers, except the throat and fore part of the neck about half way, which are not so well feathered as the rest; whereas in the common Cassowary the head and neck are bare and carunculated as in the turkey.The species was named by ornithologist John Latham in 1790 based on a specimen from the Sydney area of Australia, a country which was known as New Holland at the time.[3][10] He collaborated on Phillip's book and provided the first descriptions of, and names for, many Australian bird species; Dromaius comes from a Greek word meaning "racer" and novaehollandiae is the Latin term for New Holland, so the name can be rendered as "fast-footed New Hollander".[11] In his original 1816 description of the emu, the French ornithologist Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot used two generic names, first Dromiceius and later Dromaius.[12] It has been a point of contention ever since as to which name should be used; the latter is more correctly formed, but the convention in taxonomy is that the first name given to an organism stands, unless it is clearly a typographical error.[13] Most modern publications, including those of the Australian government,[5] use Dromaius, with Dromiceius mentioned as an alternative spelling.[5]

The plumage in general consists of a mixture of brown and grey, and the feathers are somewhat curled or bent at the ends in the natural state: the wings are so very short as to be totally useless for flight, and indeed, are scarcely to be distinguished from the rest of the plumage, were it not for their standing out a little. The long spines which are seen in the wings of the common sort, are in this not observable,—nor is there any appearance of a tail. The legs are stout, formed much as in the Galeated Cassowary, with the addition of their being jagged or sawed the whole of their length at the back part.

The etymology of the common name "emu" is uncertain, but is thought to have come from an Arabic word for large bird that was later used by Portuguese explorers to describe the related cassowary in Australia and New Guinea.[14] Another theory is that it comes from the word "ema", which is used in Portuguese to denote a large bird akin to an ostrich or crane.[7][15] In Victoria, some terms for the emu were Barrimal in the Dja Dja Wurrung language, myoure in Gunai, and courn in Jardwadjali.[16] The birds were known as murawung or birabayin to the local Eora and Darug inhabitants of the Sydney basin.[17]

Systematics

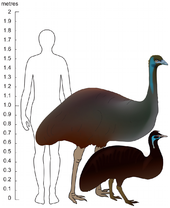

Size comparison between a human, the mainland emu (centre), and the extinct King Island sub-species (right)

| Recent paleognaths |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1912, the Australian ornithologist Gregory M. Mathews recognised three living subspecies of emu,[25] D. n. novaehollandiae (Latham, 1790),[26] D. n. woodwardi Mathews, 1912 [27] and D. n. rothschildi Mathews, 1912.[28] However, the Handbook of the Birds of the World argues that the last two of these subspecies are invalid; natural variations in plumage colour and the nomadic nature of the species make it likely that there is a single race in mainland Australia.[29][30] Examination of the DNA of the King Island emu shows this bird to be closely related to the mainland emu and hence best treated as a subspecies.[21]

Description

The emu is the second largest bird in the world, only being exceeded in size by the ostrich;[31] the largest individuals can reach up to 150 to 190 cm (59 to 75 in) in height. Measured from the bill to the tail, emus range in length from 139 to 164 cm (55 to 65 in), with males averaging 148.5 cm (58.5 in) and females averaging 156.8 cm (61.7 in).[32] Emus weigh between 18 and 60 kg (40 and 132 lb), with an average of 31.5 and 37 kg (69 and 82 lb) in males and females, respectively.[32] Females are usually slightly larger than males and are substantially wider across the rump.[33]

Emu head and upper neck

The eyes of an emu are protected by nictitating membranes. These are translucent, secondary eyelids that move horizontally from the inside edge of the eye to the outside edge. They function as visors to protect the eyes from the dust that is prevalent in windy arid regions.[33] Emus have a tracheal pouch, which becomes more prominent during the mating season. At more than 30 cm (12 in) in length, it is quite spacious; it has a thin wall, and an opening just 8 centimetres (3 in) long.[33]

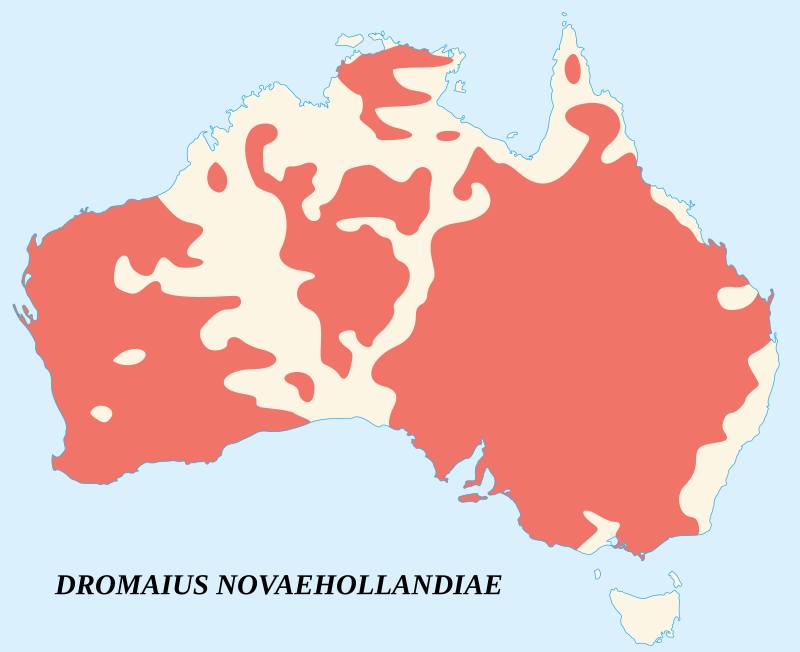

Distribution and habitat

Adult and juvenile foot prints

Behaviour and ecology

Emus are diurnal birds and spend their day foraging, preening their plumage with their beak, dust bathing and resting. They are generally gregarious birds apart from the breeding season, and while some forage, others remain vigilant to their mutual benefit.[43] They are able to swim when necessary, although they rarely do so unless the area is flooded or they need to cross a river.[35]

Emus bathing on a very hot summer day in a shallow dam

Emu grunting and hissing; note the inflating throat

On very hot days, emus pant to maintain their body temperature, their lungs work as evaporative coolers and, unlike some other species, the resulting low levels of carbon dioxide in the blood do not appear to cause alkalosis.[45] For normal breathing in cooler weather, they have large, multifolded nasal passages. Cool air warms as it passes through into the lungs, extracting heat from the nasal region. On exhalation, the emu's cold nasal turbinates condense moisture back out of the air and absorb it for reuse.[46] As with other ratites, the emu has great homeothermic ability, and can maintain this status from −5 to 45 °C (23 to 113 °F).[47] The thermoneutral zone of emus lies between 10 and 30 °C (50 and 86 °F).[47]

As with other ratites, emus have a relatively low basal metabolic rate compared to other types of birds. At −5 °C (23 °F), the metabolic rate of an emu sitting down is about 60% of that when standing, partly because the lack of feathers under the stomach leads to a higher rate of heat loss when standing from the exposed underbelly.[47]

Diet

An emu foraging in grass

Small stones are swallowed to assist in the grinding up and digestion of the plant material. Individual stones may weigh 45 g (1.6 oz) and the birds may have as much as 745 g (1.642 lb) in their gizzards at one time. They also eat charcoal, although the reason for this is unclear.[32] Captive emus have been known to eat shards of glass, marbles, car keys, jewellery, and nuts and bolts.[49]

Emus drink infrequently, but ingest large amounts when the opportunity arises. They typically drink once a day, first inspecting the water body and surrounding area in groups before kneeling down at the edge to drink. They prefer being on firm ground while drinking, rather than on rocks or mud, but if they sense danger, they often stand rather than kneel. If not disturbed, they may drink continuously for ten minutes. Due to the scarcity of water sources, emus are sometimes forced to go without water for several days. In the wild, they often share water holes with kangaroos, other birds and animals; they are wary and tend to wait for the other animals to leave before they quench their thirst.[54]

Breeding

Dark green egg

Males construct a rough nest in a semi-sheltered hollow on the ground, using bark, grass, sticks and leaves to line it.[3] The nest is almost always a flat surface rather than a segment of a sphere, although in cold conditions the nest is taller, up to 7 cm (2.8 in) tall, and more spherical to provide some extra heat retention. When other material is lacking, the bird sometimes uses a spinifex tussock a metre or so across, despite the prickly nature of the foliage.[40] The nest can be placed on open ground or near a shrub or rock. The nest is usually placed in an area where the emu has a clear view of its surroundings and can detect approaching predators.[56]

Female emus court the males; the female's plumage darkens slightly and the small patches of bare, featherless skin just below the eyes and near the beak turn turquoise-blue. The colour of the male's plumage remains unchanged, although the bare patches of skin also turn light blue. When courting, females stride around, pulling their neck back while puffing out their feathers and emitting low, monosyllabic calls that have been compared to drum beats. This calling can occur when males are out of sight or more than 50 metres (160 ft) away. Once the male's attention has been gained, the female circles her prospective mate at a distance of 10 to 40 metres (30 to 130 ft). As she does this, she looks at him by turning her neck, while at the same time keeping her rump facing towards him. If the male shows interest in the parading female, he will move closer; the female continues the courtship by shuffling further away but continuing to circle him.[40][41]

If a male is interested, he will stretch his neck and erect his feathers, then bend over and peck at the ground. He will circle around and sidle up to the female, swaying his body and neck from side to side, and rubbing his breast against his partner's rump. Often the female will reject his advances with aggression, but if amenable, she signals acceptance by squatting down and raising her rump.[41][57]

Nest and eggs

The sperm from a mating is stored by the female and can suffice to fertilise about six eggs.[57] The pair mate every day or two, and every second or third day the female lays one of a clutch of five to fifteen very large, thick-shelled, green eggs. The shell is around 1 mm (0.04 in) thick, but rather thinner in northern regions according to indigenous Australians.[3][56] The eggs are on average 13 cm × 9 cm (5.1 in × 3.5 in) and weigh between 450 and 650 g (1.0 and 1.4 lb).[58] The maternal investment in the egg is considerable, and the proportion of yolk to albumen, at about 50%, is greater than would be predicted for a precocial egg of this size. This probably relates to the long incubation period which means the developing chick must consume greater resources before hatching.[59] The first verified occurrence of genetically identical avian twins was demonstrated in the emu.[60] The egg surface is granulated and pale green. During the incubation period, the egg turns dark green, although if the egg never hatches, it will turn white from the bleaching effect of the sun.[61]

Emu chicks have longitudinal stripes that provide camouflage

Male with older juveniles

Incubation takes 56 days, and the male stops incubating the eggs shortly before they hatch.[42] The temperature of the nest rises slightly during the eight-week period. Although the eggs are laid sequentially, they tend to hatch within two days of one another, as the eggs that were laid later experienced higher temperatures and developed more rapidly.[47] During the process, the precocial emu chicks need to develop a capacity for thermoregulation. During incubation, the embryos are kept at a constant temperature but the chicks will need to be able to cope with varying external temperatures by the time they hatch.[47]

Newly hatched chicks are active and can leave the nest within a few days of hatching. They stand about 12 cm (5 in) tall at first, weigh 0.5 kg (17.6 oz),[32] and have distinctive brown and cream stripes for camouflage, which fade after three months or so. The male guards the growing chicks for up to seven months, teaching them how to find food.[32][65] Chicks grow very quickly and are fully grown in five to six months;[32] they may remain with their family group for another six months or so before they split up to breed in their second season. During their early life, the young emus are defended by their father, who adopts a belligerent stance towards other emus, including the mother. He does this by ruffling his feathers, emitting sharp grunts, and kicking his legs to drive off other animals. He can also bend his knees to crouch over smaller chicks to protect them. At night, he envelops his young with his feathers.[66] As the young emus cannot travel far, the parents must choose an area with plentiful food in which to breed.[51] In captivity, emus can live for upwards of ten years.[29]

Predation

There are few native natural predators of emus still alive. Early in its species history it may have faced numerous terrestrial predators now extinct, including the giant lizard Megalania, the thylacine, and possibly other carnivorous marsupials, which may explain their seemingly well-developed ability to defend themselves from terrestrial predators. The main predator of emus today is the dingo, which was originally introduced by Aboriginals thousands of years ago from a stock of semi-domesticated wolves. Dingoes try to kill the emu by attacking the head. The emu typically tries to repel the dingo by jumping into the air and kicking or stamping the dingo on its way down. The emu jumps as the dingo barely has the capacity to jump high enough to threaten its neck, so a correctly timed leap to coincide with the dingo's lunge can keep its head and neck out of danger.[67]Despite the potential prey-predator relationship, the presence of predaceous dingoes does not appear to heavily influence emu numbers, with other natural conditions just as likely to cause mortality.[68] Wedge-tailed eagles are the only avian predator capable of attacking fully-grown emus, though are perhaps most likely to take small or young specimens. The eagles attack emus by swooping downwards rapidly and at high speed and aiming for the head and neck. In this case, the emu's jumping technique as employed against the dingo is not useful. The birds try to target the emu in open ground so that it cannot hide behind obstacles. Under such circumstances, the emu can only run in a chaotic manner and change directions frequently to try and evade its attacker.[67][69] Other raptors, monitor lizards, introduced red foxes, feral and domestic dogs, and feral pigs occasionally feed on emu eggs or kill small chicks.[2]

Parasites

Emus can suffer from both external and internal parasites, but under farmed conditions are more parasite-free than ostriches or rheas. External parasites include the louse Dahlemhornia asymmetrica and various other lice, ticks, mites and flies. Chicks sometimes suffer from intestinal tract infections caused by coccidian protozoa, and the nematode Trichostrongylus tenuis infects the emu as well as a wide range of other birds, causing haemorrhagic diarrhoea. Other nematodes are found in the trachea and bronchi; Syngamus trachea causing haemorrhagic tracheitis and Cyathostoma variegatum causing serious respiratory problems in juveniles.[70]Relationship with humans

Aboriginal emu caller, used to arouse the curiosity of emus

The early European settlers killed emus to provide food and used their fat for fuelling lamps.[71] They also tried to prevent them from interfering with farming or invading settlements in search of water during drought. An extreme example of this was the Emu War in Western Australia in 1932. Emus flocked to the Chandler and Walgoolan area during a dry spell, damaging rabbit fencing and devastating crops. An attempt to drive them off was mounted, with the army called in to dispatch them with machine guns; the emus largely avoided the hunters and won the battle.[71][72] Emus are large, powerful birds, and their legs are among the strongest of any animal and powerful enough to tear down metal fencing.[35] The birds are very defensive of their young, and there have been two documented cases of humans being attacked by emus.[73][74]

Economic value

In the areas in which it was endemic, the emu was an important source of meat to Aboriginal Australians. They used the fat as bush medicine and rubbed it into their skin. It served as a valuable lubricant, was used to oil wooden tools and utensils such as the coolamon, and was mixed with ochre to make the traditional paint for ceremonial body adornment.[75]An example of how the emu was cooked comes from the Arrernte of Central Australia who called it Kere ankerre:

"Emus are around all the time, in green times and dry times. You pluck the feathers out first, then pull out the crop from the stomach, and put in the feathers you've pulled out, and then singe it on the fire. You wrap the milk guts that you've pulled out into something [such as] gum leaves and cook them. When you've got the fat off, you cut the meat up and cook it on fire made from river red gum wood."[76]

Farmed emu being grain fed

The Salem district administration in India advised farmers in 2012 not to invest in the emu business which was being heavily promoted at the time; further investigation was needed to assess the profitability of farming the birds in India.[80] In the United States, it was reported in 2013 that many ranchers had left the emu business; it was estimated that the number of growers had dropped from over five thousand in 1998 to one or two thousand in 2013. The remaining growers increasingly rely on sales of oil for their profit, although, leather, eggs, and meat are also sold.[81]

1807 plate showing now extinct island emus taken to France for breeding purposes in 1804

There is some evidence that the oil has anti-inflammatory properties;[83] however, there have not yet been extensive tests,[82] and the USDA regards pure emu oil as an unapproved drug and highlighted it in a 2009 article entitled "How to Spot Health Fraud".[84] Nevertheless, the oil has been linked to the easing of gastrointestinal inflammation, and tests on rats have shown that it has a significant effect in treating arthritis and joint pain, more so than olive or fish oils.[85] It has been scientifically shown to improve the rate of wound healing, but the mechanism responsible for this effect is not understood.[85] A 2008 study has claimed that emu oil has a better anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory potential than ostrich oil, and linked this to emu oil's higher proportion of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids.[83][85][86] While there are no scientific studies showing that emu oil is effective in humans, it is marketed and promoted as a dietary supplement with a wide variety of claimed health benefits. Commercially marketed emu oil supplements are poorly standardised.[87]

Emu leather has a distinctive patterned surface, due to a raised area around the feather follicles in the skin; the leather is used in such items as wallets, handbags, shoes and clothes,[81] often in combination with other leathers. The feathers and eggs are used in decorative arts and crafts. In particular, emptied emu eggs have been engraved with portraits, similar to cameos, and scenes of Australian native animals.[88]

Cultural references

The Aboriginal "Emu in the sky". In Western astronomy terms, the Southern Cross is on the right, and Scorpius on the left; the head of the emu is the Coalsack.

Coat of Arms of Australia

The emu on a postage stamp of Australia issued in 1942

The emu is popularly but unofficially considered as a faunal emblem – the national bird of Australia.[93] It appears as a shield bearer on the Coat of arms of Australia with the red kangaroo, and as a part of the Arms also appears on the Australian 50 cent coin.[93][94] It has featured on numerous Australian postage stamps, including a pre-federation New South Wales 100th Anniversary issue from 1888, which featured a 2 pence blue emu stamp, a 36 cent stamp released in 1986, and a $1.35 stamp released in 1994.[95] The hats of the Australian Light Horse are decorated with emu feather plumes.[96]

There are around six hundred gazetted places in Australia with "emu" in their title, including mountains, lakes, hills, plains, creeks and waterholes.[97] During the 19th and 20th centuries, many Australian companies and household products were named after the bird. In Western Australia, Emu beer has been produced since the early 20th century and the Swan Brewery continues to produce a range of beers branded as "Emu".[98] The quarterly peer-reviewed journal of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union, also known as Birds Australia, is entitled Emu: Austral Ornithology.[99]

The comedian Rod Hull featured a wayward emu puppet in his act for many years and the bird returned to the small screen in the hands of his son after the puppeteer's untimely death.[100]

Status and conservation

John Gerrard Keulemans's (c. 1910) restoration of the Tasmanian emu, one of two sub-species which were hunted out of existence

Although the population of emus on mainland Australia is thought to be higher now than it was before European settlement,[14] some local populations are at risk of extinction. The threats faced by emus include the clearance and fragmentation of areas of suitable habitat, deliberate slaughter, collisions with vehicles and predation of the eggs and young.[2]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.