Classification

The species was first described by Titian Peale in 1848. The genus Lissodelphis is placed within the Delphinidae, the oceanic dolphin family of cetaceans.[2] The epithet of the genus was derived from Greek lisso, smooth, and delphis;[3] the specific epithet, borealis, indicates the northern distribution. The common names for the species formerly included northern right whale porpoise, snake porpoise, and Pacific right whale porpoise.[4][5] Both species in the genus are also referred to by the name right whale dolphin, a name derived from the right whales Eubalaena, which also lack a dorsal fin.[3][6]Characteristics

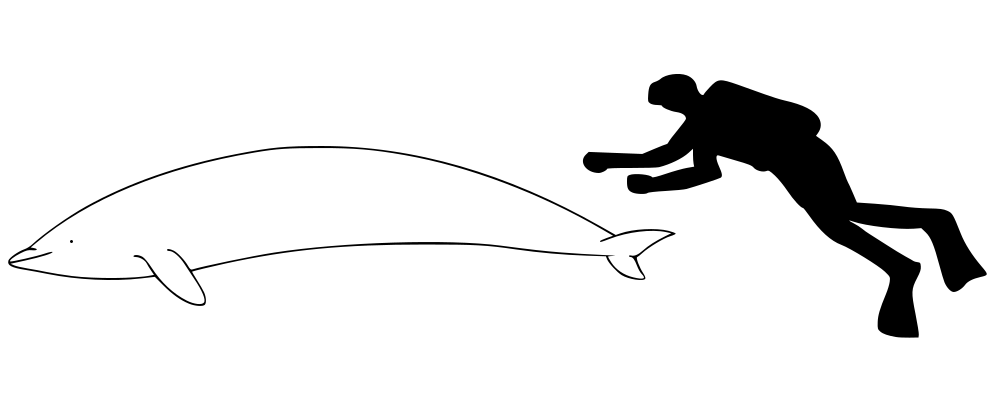

This dolphin has a streamlined body with a sloping forehead, being more slender than other delphinids, and lacks any fin or ridge on the smoothly curving back.[7][8] The beak is short and well defined, a straight mouthline, and an irregular white patch on chin. The flippers are small, curved, narrow and pointed. The body is mostly black with a white marking extending forward as a narrow band from the caudal peduncle, expanding into a wide thoracic patch. In females, this white band is wider in the genital area than in males.[9] The tail flukes are triangular and, like the flippers, pointed. Adults weigh between 60–100 kg (130–220 lb).[7] They have 74 to 108 thin and sharp teeth, not externally visible.[8] As young calves, these dolphins are greyish brown or som[9] etimes cream. They stay like this for a year, before their body turns mainly black, with a clear white belly, and a white streak to their lower jaw.Adults range around 2–3 m (6 ft 7 in–9 ft 10 in) in length; females are recorded as 2.3–2.6 m (7 ft 7 in–8 ft 6 in), males at 3.1 m (10 ft), the sexes are otherwise similar in color and appearance.[4][8] Newborns are around 90 cm (35 in). Northern right whale dolphins have less white on their bodies than the southern species.

Northern right whale dolphins are found as individuals or in groups as large as 2000.[7] The group's average number is 110 in the eastern North Pacific and 200 individuals in the western North Pacific. They often associate with Pacific white-sided dolphins, but have also been reported with Dall’s porpoise (Phocoenoides dalli), Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus), Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii), Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) and others.[8][9]

They can reach speeds up to 30–40 km/h (19–25 mph) across the open ocean, and sometimes along shallow coasts. They can dive up to 200 m (660 ft) in search of fish, especially lanternfish, and squid.[8] They are found in temperate to cold waters, 24 to 8 °C (75 to 46 °F), from latitudes 51°N to 31°N between the west coast of North America and Asia. Lissodelphis borealis has been reported as far south as 29° N latitude, off Baja California, Mexico, during periods of unseasonably low water temperatures.[10] They tend to move southward and inshore in late fall, and northward and offshore in spring.[9]

Yankee whalers occasionally took this species for food in the mid-19th century.[11] Records from the late 20th century show large numbers of L. borealis were caught in drift nets, used for large-scale squid fishing, which is estimated to have reduced the population by one- to three-quarters.[8] Although the current population trend is unknown, IUCN Redlist gives the conservation status as Least Concern.[1]

Behavior

When travelling fast, a group looks as though they are bouncing along on the water, as they make low leaps together, sometimes travelling as far as 7 m in one leap. They often approach boats and partake in bow-riding behavior. These graceful swimmers are spotted occasionally doing acrobatics, such as breaching, belly-flopping, side slapping, and lobtailing.Reproduction

Within this species, is estimated to reach sexual maturity between 8 to 11 years in males is estimated and between 8 and 12 years in females. Researchers found that there is an increase in secondary growth among some animals at 11 – 15 years of age, with an asymptotic 265 cm and is also characterized by an increase in testis weight. This testicular growth has an apparent correlation with reaching social maturity in L. borealis and it has been reported in other odontocetes such as killer whale (Orcinus orca), sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), pilot whale (Globicephala spp.), the spotted dolphin (Stenella attenuata) and the eastern spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris). On the other hand, mature females present ovarian scars indicated that 1-20 corpora were present. In general, the summer calving season reaches its peaks in early July until August. In this species, the gestation period is of approximately 12 months.[12]Sensory system

Unlike most delphinidae, L. borealis vocalizes without the use of whistles. Most visual and audio surveys have confirmed vocalization to primarily be through clicks and burst pulses.[13],[14] L. borealis have repetitive, repetitive, burst-pattern pulses, that can be categorized and associated within L. borealis subgroups. These are hypothesized to be used as patterns of communication between individuals in a similar way to signature whistles in other delfinid species.[13] The evolution of the loss of whistling stemmed from a number of factors; predator avoidance, school size, school species composition, etc. The question of why L. borealis may benefit from the lack of whistle communication has yet to be explored.[15]Population Status

Lissodelphis borealis is currently listed in the least concern category by the IUCN.[12] The reasoning for this classification is that L. borealis is thought to have an abundant population throughout the North Pacific Ocean. All estimates of total population are uncertain, but the recorded population off the West Coast of the US has an estimated 9,000 to 21,000 individuals.[12] The current population trend remains unknown.[9]Predators and Other Major Threats

Natural predators of Lissodelphis borealis are unknown, but may include the Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) and large sharks. Stranding events are uncommon in this species.[9]One of the largest threats that the L. borealis faced was high-sea driftnets.[16] During the most intense period of the high-sea drift net fishery in 1978, the population stock of L. borealis declined anywhere between 24% - 73%.[16] This large discrepancy in the estimate of the population’s decline is due to uncertainty of which population was recorded for the decline. It is estimated that about 15,000 to 24,000 individuals were killed by driftnets used in the squid fishery in the North Pacific.[12]

One reason why the use of high-sea drift nets is so detrimental to the population of the Lissodelphis borealis is because this species is often found in large aggregations, and a drift net has the potential to decimate an entire pod.[16] This fundamental behavior for hunting makes the population dynamics of L. borealis more susceptible to threats that have the capability of killing many individuals simultaneously.

Protection

Regulation of international trade between members of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora 1973 (CITES)- and between non-members and Convention members- has been established by listing the Northern Right Whale Dolphin under Appendix II of the Convention. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) has not yet regulated the taking of these odontocetes.[9]

In Canada, the 1982 Cetacean Protection Regulations of the Fisheries Act of Canada prohibit hunting of L. borealis and other related species. The exception to this rule are aboriginal peoples, who are allowed to take whales for subsistence purposes. In the United States, all cetaceans are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, as well as through the Packwood - Magnuson Amendment of the Fisheries and Conservation Act, and the Pelly Amendment of the Fisherman’s Protective Act.[9]

One of the most effective conservation measures for L. borealis was the U.N. sanction on the high-seas driftnet fisheries.[12] The high-seas driftnet fishery has been required by law to use pingers- devices that deliver an acoustic warning into the water column to help reduce the bycatch of L. borealis and other cetaceans around the globe.

The offshore habitat of the Northern Right Whale Dolphin is generally less susceptible to human impact and degradation than coastal areas.[9]

Range map

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.