The Beringian wolf was similar in size to the modern Yukon wolf (Canis lupus pambasileus) and other Late Pleistocene gray wolves but more robust and with stronger jaws and teeth, a broader palate, and larger carnassial teeth relative to its skull size. In comparison with the Beringian wolf, the more southerly occurring dire wolf (Canis dirus) was the same size but heavier and with a more robust skull and dentition. The unique adaptation of the skull and dentition of the Beringian wolf allowed it to produce relatively large bite forces, grapple with large struggling prey, and therefore made predation and scavenging on Pleistocene megafauna possible. The Beringian wolf preyed most often on horse and steppe bison, and also on caribou, mammoth, and woodland muskox.

At the close of the Ice Age, with the loss of cold and dry conditions and the extinction of much of its prey, the Beringian wolf became extinct. The extinction of its prey has been attributed to the impact of climate change, competition with other species, including humans, or a combination of both factors. Local genetic populations were replaced by others from within the same species or of the same genus. Of the North American wolves, only the ancestor of the modern North American gray wolf survived. The remains of ancient wolves with similar skulls and dentition have been found in western Beringia (north-east Siberia). In 2016 a study showed that some of the wolves now living in remote corners of China and Mongolia share a common maternal ancestor with one 28,000-year-old eastern Beringian wolf specimen.

Taxonomy

From the 1930s representatives of the American Museum of Natural History worked with the Alaska College and the Fairbanks Exploration Company to collect specimens uncovered by hydraulic gold dredging near Fairbanks, Alaska. Childs Frick was a research associate in paleontology with the American Museum who had been working in the Fairbanks region. In 1930, he published an article which contained a list of "extinct Pleistocene mammals of Alaska-Yukon". This list included one specimen of what he believed to be a new subspecies which he named Aenocyon dirus alaskensis - the Alaskan dire wolf.[1] The American museum referred to these as a typical Pleistocene species in Fairbanks.[2] However, no type specimen, description nor exact location was provided, and because dire wolves had not been found this far north this name was later proposed as nomen nudum (invalid) by the paleontologist Ronald M. Nowak.[3] Between 1932 and 1953 twenty-eight wolf skulls were recovered from the Ester, Cripple, Engineer, and Little Eldorado creeks located north and west of Fairbanks. The skulls were thought to be 10,000 years old. The geologist and paleontologist Theodore Galusha, who helped amass the Frick collections of fossil mammals at the American Museum of Natural History, worked on the wolf skulls over a number of years and noted that, compared with modern wolves, they were "short-faced".[4] The paleontologist Stanley John Olsen continued Galusha's work with the short-faced wolf skulls, and in 1985, based on their morphology, he classified them as Canis lupus (gray wolf).[5]Gray wolves were widely distributed across North American during both the Pleistocene and historic period.[6] In 2007 Jennifer Leonard undertook a study based on the genetic, morphology, and stable isotope analyses of seventy-four Beringian wolf specimens from Alaska and the Yukon that revealed the genetic relationships, prey species, and feeding behavior of prehistoric wolves, and supported the classification of this wolf as C. lupus.[7][8] The specimens were not assigned a subspecies classification by Leonard, who referred to these as "eastern Beringian wolves".[9] A subspecies was possibly not assigned because the relationship between the Beringian wolf and the extinct European cave wolf (C. l. spelaeus) is not clear. Beringia was once an area of land that spanned the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Sea, joining Eurasia to North America. Eastern Beringia included what is today Alaska and the Yukon.[10]

Lineage

Basal wolf

DNA sequences can be mapped to reveal a phylogenetic tree that represents evolutionary relationships, with each branch point representing the divergence of two lineages from a common ancestor. On this tree the term basal is used to describe a lineage that forms a branch diverging nearest to the common ancestor.[11] Wolf genetic sequencing has found the Beringian wolf to be basal to all other gray wolves except for the modern Indian gray wolf and Himalayan wolf,[8] and the extinct Belgian clade of Pleistocene wolves.[12][13]Different genetic types of gray wolf

| Phylogenetic tree for wolves | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified mDNA phylogeny for modern wolves and extinct Beringian wolves[8][14] |

Artist's impression of the Beringian wolf

A scenario consistent with the phylogenetic, ice sheet size, and sea-level depth data is that during the Late Pleistocene the sea levels were at their lowest. A single wave of wolf colonization into North America commenced with the opening of the Bering land bridge 70,000 YBP. It ended with the closing of the Yukon corridor that ran along the division between the Laurentide Ice Sheet and the Cordilleran Ice Sheet 23,000 YBP during the Late Glacial Maximum. As wolves had been in the fossil record of North America but the genetic ancestry of modern wolves could be traced back only 80,000 years,[12][13] the wolf haplotypes that were already in North America were replaced by these invaders, either through competitive displacement or through genetic admixture. The replacement in North America of a basal population of wolves by a more recent one is consistent with the findings of earlier studies.[8][13][14]

The Beringian wolves are morphologically and genetically comparable to Late Pleistocene European wolves.[23] One study found that ancient wolves across Eurasia had a mDNA sequence identical to six Beringian wolves (indicating a common maternal ancestor). These wolves included a wolf from the Nerubajskoe-4 Paleolithic site, near Odessa, Ukraine, dated 30,000 YBP, a wolf from the Zaskalnaya-9 Paleolithic site, in Zaskalnaya on the Crimean Peninsula, dated 28,000 YBP, and the "Altai dog" from the Altai Mountains of Central Asia dated 33,000 YBP. Another wolf from the Vypustek cave, Czech Republic, dated 44,000 YBP had a mDNA sequence identical to two Beringian wolves (indicating another common maternal ancestor).[8] The Beringian wolves are phylogenetically associated with a distinct group of four modern European mDNA haplotypes, which indicates that both ancient and extant North American wolves originated in Eurasia.[8] Of these four modern haplotypes, one was only found in the Italian wolf and one only found among wolves in Romania.[24] These four haplotypes fall, along with those of the Beringian wolves, under mDNA haplogroup 2.[14] Ancient specimens of wolves with similar skull and dentition have been found in western Beringia (northeast Siberia), the Taimyr Peninsula, the Ukraine, and Germany, where the European specimens are classified as Canis lupus spelaeus – the cave wolf.[25] The Beringian wolves, and perhaps wolves across the mammoth steppe, were adapted to preying on now-extinct species through their unique skull and tooth morphology.[26] This type of gray wolf that is adapted for preying on megafauna has been referred to as the Megafaunal wolf.[27]

It is possible that a panmictic (random mating) wolf population, with gene flow spanning Eurasia and North America, existed until the closing of the ice sheets,[13][14][28] after which the southern wolves became isolated, and only the Beringian wolf existed north of the sheets. The land bridge became inundated by the sea 10,000 YBP, and the ice sheets receded 12,000—6,000 YBP.[13] The Beringian wolf became extinct, and the southern wolves expanded through the shrinking ice sheets to recolonize the northern part of North America.[13][28] All North American wolves are descended from those that were once isolated south of the ice sheets. However, much of their diversity was later lost during the twentieth century due to eradication.[13][19]

Description

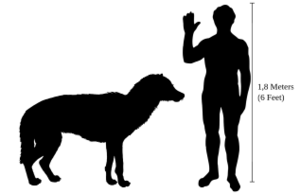

Beringian wolf size compared to a human

The proportions of the skulls of these wolves that vary do so in the rostral area. The area of the skull that is anterior to the infraorbital foramen is noticeably foreshortened and constricted laterally in several of the skulls...Dishing of the rostrum, when viewed laterally, is evident in all of the short-faced skulls identified as Canis lupus from the Fairbanks gold fields. The occipital and supraoccipital crests are noticeably diminished compared to those found in average specimens of C. lupus. The occipital overhang of these crests, a wolf characteristic, is about equal in both groups of C. lupus...Examination of a large series of recent wolf skulls from the Alaskan area did not produce individuals with the same variations as those from the Fairbanks gold fields.[5]The Beringian wolf was similar in size to the modern Yukon wolf (C. l. pambasileus).[8] The largest northern wolves today have a shoulder height not exceeding 97 cm (38 in) and a body length not exceeding 180 cm (71 in).[29] The average weight of the Yukon wolf is 43 kg (95 lb) for males and 37 kg (82 lb) for females. Individual weights for Yukon wolves can vary from 21 kg (46 lb) to 55 kg (121 lb),[30] with one Yukon wolf weighing 79.4 kg (175 lb).[29] The Beringian wolves were also similar in size to the Late Pleistocene wolves whose remains have been found in the La Brea Tar Pits at Los Angeles, California.[8] These wolves, referred to as Rancho La Brea wolves (Canis lupus), were not physically different from modern gray wolves, the only differences being a broader femur bone and a longer tibial tuberosity – the insertion for the quadriceps and hamstring muscles – indicating that they had comparatively more powerful leg muscles for a fast take-off before a chase.[31] The Beringian wolf was more robust, and possessed stronger jaws and teeth, than either Rancho La Brea or modern wolves.[8][18]

During the Late Pleistocene, the more southerly occurring dire wolf (Canis dirus) had the same shape and proportions as the Yukon wolf,[32][33] but the dire wolf subspecies C. dirus guildayi is estimated to have weighed on average 60 kg (130 lb), and the subspecies C. dirus dirus on average 68 kg (150 lb), with some specimens being larger.[34] The dire wolf was heavier than the Beringian wolf and possessed a more robust skull and dentition.[8]

Adaptation

Adaptation is the evolutionary process by which an organism becomes better able to live in its environment.[35] The genetic differences between wolf populations is tightly associated with their type of habitat, and wolves disperse primarily within the type of habitat that they were born into.[26] Ecological factors such as habitat type, climate, prey specialization, and predatory competition have been shown to greatly influence gray wolf craniodental plasticity, which is an adaptation of the cranium and teeth due to the influences of the environment.[26][36][37] In the Late Pleistocene the variations between local environments would have encouraged a range of wolf ecotypes that were genetically, morphologically, and ecologically distinct from each another.[36] The term ecomorph is used to describes a recognizable association of the morphology of an organism or a species with their use of the environment.[38] The Beringian wolf ecomorph shows evolutionary craniodental plasticity not seen in past nor present North American gray wolves,[8] and was well-adapted to the megafauna-rich environment of the Late Pleistocene.[8][9]Paleoecology

Beringia precipitation 22,000 years ago

During the Ice Age a vast, cold and dry mammoth steppe stretched from the Arctic islands southwards to China, and from Spain eastwards across Eurasia and over the Bering land bridge into Alaska and the Yukon, where it was blocked by the Wisconsin glaciation. The land bridge existed because sea levels were lower due to more of the planet's water being locked up in glaciers compared with today. Therefore, the flora and fauna of Beringia were more related to those of Eurasia rather than to those of North America.[43][44] In eastern Beringia from 35,000 YBP the northern Arctic areas experienced temperatures 1.5°C (2.7°F) warmer than today, but the southern sub-Arctic regions were 2°C (3.5°F) cooler. In 22,000 YBP, during the Last Glacial Maximum, the average summer temperature was 3-5°C (5.4-9°F) cooler than today, with variations of 2.9°C (5.2°F) cooler on the Seward Peninsula to 7.5°C (13.5°F) cooler in the Yukon.[45]

Beringia received more moisture and intermittent maritime cloud cover from the north Pacific Ocean than the rest of the Mammoth steppe, including the dry environments on either side of it. Moisture occurred along a north-south gradient with the south receiving the most cloud cover and moisture due to the airflow from the North Pacific.[44] This moisture supported a shrub-tundra habitat that provided an ecological refugium for plants and animals.[43][44] In this Beringian refugium, eastern Beringia's vegetation included isolated pockets of larch and spruce forests with birch and alder trees.[46][47][48][49] This environment supported large herbivores that were prey for Beringian wolves and their competitors. Steppe bison (Bison priscus), Yukon horse (Equus lambei), woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), and Wild yak (Bos mutus) consumed grasses, sedges, and herbaceous plants. Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and woodland muskox (Symbos cavifrons) consumed tundra plants, including lichen, fungi, and mosses.[10]

Prey

Bison surrounded by a gray wolf pack. Beringian wolves preyed most often on steppe bison and horse.

In another stable isotope analysis, half of the Beringian wolves were found to be musk ox and caribou specialists, and the other half were either horse and bison specialists or generalists. Two wolves from the full-glacial period (23,000–18,000 YBP) were found to be mammoth specialists, but it is not clear if this was due to scavenging or predation. The analysis of other carnivore fossils from the Fairbanks region of Alaska found that mammoth was rare in the diets of the other Beringian carnivores.[10]

Dentition

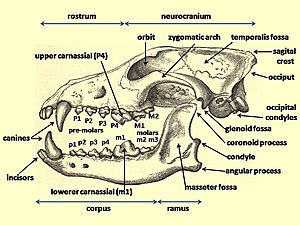

A 2007 study of Canis dentition shows that in comparison with the modern gray wolf and the Pleistocene La Brea wolf, the Beringian wolf possessed large carnassial teeth[8] and a short, broad palate relative to the size of its skull.[6][8] The row length of the Beringian wolf's premolars was longer, the P4 premolar (the upper carnassial) longer and wider, and the M1, M2, and m1 (the lower carnassial) molars longer than those found in the other two types of wolves. The Beringian wolf's short, broad rostrum increased the force of a bite made with the canine teeth while strengthening the skull against the stresses caused by struggling prey. Today, the relatively deep jaws similar to those of the Beringian wolf can be found in the bone-cracking spotted hyena and in those canids that are adapted for taking large prey.[8] Beringian wolves possessed a craniodental morphology that was more specialized than modern gray wolves and Rancho La Brea wolves for capturing, dismembering, and consuming the bones of very large megaherbivores,[8][20] having evolved this way due to the presence of megafauna.[52] Their stronger jaws and teeth indicate a hypercarnivorous lifestyle.[8][18]An accepted sign of domestication is the presence of tooth crowding, in which the orientation and alignment of the teeth are described as touching, overlapping or being rotated. A 2017 study found that 18% of Beringian wolf specimens exhibit tooth crowding compared with 9% for modern wolves and 5% for domestic dogs. These specimens predate the arrival of humans and therefore there is no possibility of cross-breeding with dogs. The study indicates that tooth crowding can be a natural occurrence in some wolf ecomorphs and cannot be used to differentiate ancient wolves from early dogs.[53]

Diagram of a wolf skull with key features labelled

| Tooth variable | modern North America | Rancho La Brea | Eastern Beringia |

|---|---|---|---|

| premolar row length | 63.4 | 63.6 | 69.3 |

| palate width | 64.9 | 67.6 | 76.6 |

| P4 length | 25.1 | 26.3 | 26.7 |

| P4 width | 10.1 | 10.6 | 11.4 |

| M1 length | 16.4 | 16.5 | 16.6 |

| M2 length | 8.7 | 8.9 | 9.2 |

| m1 length | 28.2 | 28.9 | 29.6 |

| m1 trigonid length | 19.6 | 21.9 | 20.9 |

| m1 width | 10.7 | 11.3 | 11.1 |

Tooth breakage

Dentition of an Ice Age wolf showing functions of the teeth

Competitors

In addition to the Beringian wolf, other Beringian carnivores include the Beringian cave lion (Panthera leo spelaea), scimitar-toothed cat (Homotherium serum), short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), and the omnivorous brown bear (Ursus arctos).[10] Beringian wolves would have faced competition for the carcasses of large herbivores from the formidable short-faced bear, a scavenger.[58] Additionally, humans had reached the Bluefish Caves in the Yukon Territory by 24,000 YBP, with cutmarks being found there on specimens of Yukon horse, steppe bison, caribou, wapiti (Cervus elaphus), and Dall sheep (Ovis dalli).[59]A 1993 study proposed that the higher frequency of tooth breakage among Pleistocene carnivores compared with living carnivores was not the result of hunting larger game, something that might be assumed from the larger size of the former. When there is low prey availability, the competition between carnivores increases, causing them to eat faster and consume more bone, leading to tooth breakage.[54][60][61] Compared to modern wolves, the high frequency of tooth fracture in Beringian wolves indicates higher carcass consumption due to higher carnivore density and increased competition.[8]

Range

Path

of Beringian wolves from Alaska to the Natural Trap Cave, Wyoming

(denoted with a black dot). Dog icons represent sites where Beringian

wolves have previously been found, and paw prints represent the proposed

path through the ice sheets.[9]

Extinction

Ubsunur Hollow Biosphere Reserve on the border between Russia and Mongolia, is one of the last remnants of the mammoth steppe.

Phenotype is extinct

A phenotype is any observable and measurable characteristic of an organism and includes any morphological, behavioral, and physiological traits,[66] with these characteristics being influenced by genes and the environment.[67] The mammoth steppe lasted for 100,000 years without change until it came to an end around 12,000 years ago.[44] The American megafaunal extinction event occurred 12,700 YBP when 90 genera of mammals weighing over 44 kilograms (97 lb) became extinct.[68][60] The extinction of the large carnivores and scavengers is thought to have been caused by the extinction of the megaherbivore prey upon which they depended.[69][70] The cause of the extinction of this megafauna is debated[57] but has been attributed to the impact of climate change, competition with other species, including humans, or a combination of both factors.[57][71] For those mammals with modern representatives, ancient DNA and radiocarbon data indicate that the local genetic populations were replaced by others from within the same species or by others of the same genus.[72]

Phylogenetic

tree based on the mDNA of wolves. The modern wolf clade XVI from

China/Mongolia shares a haplotype with a Beringian wolf (Alaska 28,000

YBP).

The radiocarbon dating of the skeletal remains from 56 Beringian wolves showed a continuous population from over 50,800 YBP[22] until 12,500 YBP, followed by one wolf dated at 7,600 YBP. This indicates that their population was in decline after 12,500 YBP,[8] although megafaunal prey was still available in this region until 10,500 YBP.[73] The timing of this latter specimen is supported by the recovery of mammoth and horse DNA from sediments dated 10,500 YBP–7,600 YBP from the interior of Alaska.[73] The timing for the extinction of horses in North America and the minimum population size for North American bison coincide with the extinction of an entire wolf haplogroup in North America, indicating that the disappearance of their prey caused the extinction of this wolf ecomorph.[18][20] This resulted in a significant loss of phenotypic and genetic diversity within the species.[8]

Haplotype is not extinct

There are parts of Central Eurasia where the environment is considered to be stable over the past 40,000 years.[74] In 2016 a study compared mDNA sequences of ancient wolf specimens with those from modern wolves, including specimens from the remote regions of North America, Russia, and China. One ancient haplotype that had once existed in both Alaska (Eastern Beringia 28,000 YBP) and Russia (Medvezya "Bear" Cave, Pechora area, Northern Urals 18,000 YBP) was shared by modern wolves found living in Mongolia and China (indicating a common maternal ancestor). The study found that the genetic diversity of past wolves was lost at the beginning of the Holocene in Alaska, Siberia, and Europe, and that there is limited overlap with modern wolves. The study did not support two wolf haplogroups that had been proposed by earlier studies. For the ancient wolves of North America, instead of an extinction/replacement model indicated by other studies, this study found substantial evidence of a population bottleneck (reduction) in which the ancient wolf diversity was almost lost at the beginning of the Holocene. In Eurasia, the loss of many ancient lineages cannot be simply explained and appears to have been slow across time with reasons unclear.[22]

Animated map showing Beringia sea levels measured in meters from 21,000 years ago to present. Beringia once spanned the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Sea, joining Eurasia to North America.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.