The name ermine /ˈɜːrmɪn/ is used for any species in the genus Mustela, especially the stoat, in its pure white winter coat, or the fur thereof.[2]

The stoat is classed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as least concern, due to its wide circumpolar distribution, and because it does not face any significant threat to its survival.[1] In the late 19th century, stoats were introduced into New Zealand to control rabbits, where they have had a devastating effect on native bird populations. It was nominated as one of the world's top 100 "worst invaders".[3]

Ermine luxury fur was used in the 15th century by Catholic monarchs, who sometimes used it as the mozzetta cape. It was also used in capes on images such as the Infant Jesus of Prague.

Etymology

Skull of a stoat

Evolution

Skulls of a long-tailed weasel (top), a stoat (bottom left) and least weasel (bottom right), as illustrated in Merriam's Synopsis of the Weasels of North America

Combined phylogenetic analyses indicate the stoat's closest living relative is the mountain weasel (Mustela altaica), though it is also closely related to the least weasel (Mustela nivalis) and long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata). Its next closest relatives are the New World Colombian weasel (Mustela felipei) and the Amazon weasel (Mustela africana).[10]

Subspecies

As of 2005,[11] 37 subspecies are recognized.| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern stoat M. e. erminea (Nominate subspecies) |

Linnaeus, 1758 | A small-to-medium-sized subspecies with a relatively short and broad facial region[12] | The Kola Peninsula, Scandinavia | hyberna (Kerr, 1792) maculata (Billberg, 1827) |

| Middle Russian stoat M. e. aestiva

|

Kerr, 1792 | A moderately sized subspecies with dark, tawny or chestnut summer fur[12] | European Russia (except for the Kola Peninsula), Central and Western Europe | algiricus (Thomas, 1895) alpestris (Burg, 1920) giganteus (Burg, 1920) major (Nilsson, 1820) |

| Junean stoat M. e. alascensis |

Merriam, 1896 | Similar to M. e. richardsonii, but with a broader skull and more extensive white tips on the limbs[13] | Juneau, Alaska | |

| Vancouver Island stoat M. e. anguinae |

Hall, 1932 | Vancouver Island | ||

| Tundra stoat M. e. arctica

|

Merriam, 1826 | A large subspecies, with a dark yellowish-brown summer coat, a deep yellow underbelly and a massive skull; it resembles the Eurasian stoat subspecies more closely than any other American stoat subspecies[14] | Alaska, northwestern Canada, and the Arctic archipelago (except for Baffin Island) | audax (Barrett-Hamilton, 1904) kadiacensis (Merriam, 1896) kadiacensis (Osgood, 1901) richardsonii (Bonaparte, 1838) |

| M. e. augustidens | Brown, 1908 | |||

| Western Great Lakes stoat M. e. bangsi |

Hall, 1945 | The region west of the Great Lakes | cicognani (Mearns, 1891) pusillus (Aughey, 1880) | |

| Mustela e. celenda | Hall, 1944 | |||

| Bonaparte's stoat M. e. cigognanii

|

Bonaparte, 1838 | A small subspecies with a dark brown summer coat; its skull is more lightly built than that of richardsonii.[15] | The region north and east of the Great Lakes | pusilla (DeKay, 1842) vulgaris (Griffith, 1827) |

| M. e. fallenda | Hall, 1945 | |||

| Fergana stoat M. e. ferghanae |

Thomas, 1895 | A small subspecies; it has a very light, straw-brownish or greyish coat, which is short and soft. Light spots, sometimes forming a collar, are present on the neck. It does not turn white in winter.[16] | The montane Tien Shan and Pamir-Alaisk system, Afghanistan, India, western Tibet and the adjacent parts of the Tien Shan in China | shnitnikovi (Ognev, 1935) whiteheadi (Wroughton, 1908) |

| Mustela e. gulosa | Hall, 1945 | |||

| Queen Charlotte Islands stoat M. e. haidarum |

Preble, 1898 | The Queen Charlotte Islands | ||

| Irish stoat M. e. hibernica

|

Thomas and Barrett-Hamilton, 1895 | Larger than aestiva, but smaller than stabilis; it is distinguished by the irregular pattern on the dividing line between the dark and pale fur on the flanks, though 13.5% of Irish stoats exhibit the more typical straight dividing line.[17] | Ireland and the Isle of Man | |

| M. e. initis | Hall, 1945 | |||

| M. e. invicta | Hall, 1945 | |||

| Kodiak stoat M. e. kadiacensis |

Merriam, 1896 | Kodiak Island | ||

| East Siberian stoat M. e. kaneii |

Baird, 1857 | A moderately sized subspecies; it is smaller than M. e. tobolica, with close similarities to M. e. arctica. The colour of the summer coat is relatively light, with varying intensities of browning-yellow tinges.[18] | Eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East including Kamchatka, except the Amur Oblast and Ussuriland, Transbaikalia and the Sayan Mountains | baturini (Ognev, 1929) digna (Hall, 1944) kamtschatica (Dybowski, 1922) kanei (G. Allen, 1914) naumovi (Jurgenson, 1938) orientalis (Ognev, 1928) transbaikalica (Ognev, 1928) |

| Karaginsky stoat M. e. karaginensis |

Jurgenson, 1936 | A very small subspecies with a light chestnut-coloured summer coat[19] | Karaginsky Island, along the eastern coast of Kamchatka | |

| Altai stoat Mustela e. lymani |

Hollister, 1912 | A moderately sized subspecies with less dense fur than M. e. tobolica; the colour of its summer coat consists of weakly developed reddish-brown tones. The skull is similar to that of M. e. aestiva.[18] | The mountains of southern Siberia eastwards to Baikal and the contiguous parts of Mongolia | |

| M. e. martinoi | Ellerman and Morrison-Scott, 1951 | birulai (Martino and Martino, 1930) | ||

| Swiss stoat M. e. minima |

Cavazza, 1912 | Switzerland | ||

| Gobi stoat}} M. e. mongolica | Ognev, 1928 | The Govi-Altai Province | ||

| Southwestern stoat M. e. muricus |

Bangs, 1899 | The southwestern extremity of the species' American range (Nevada, Utah, Colorado and other states) | leptus (Merriam, 1903) | |

| Japanese stoat M. e. nippon

|

Cabrera, 1913 | Japan | ||

| M. e. ognevi | Jurgenson, 1932 | |||

| Olympic stoat}} M. e. olympica | Hall, 1945 | The Olympic Peninsula, Washington | ||

| Polar stoat M. e. polaris |

Barrett-Hamilton, 1904 | Greenland | ||

| Richardson's stoat M. e. richardsonii |

Bonaparte, 1838 | Similar to M. e. cigognanii, but larger, with a dull chocolate brown summer coat[15] | Newfoundland, Labrador and nearly all of Canada (save for the ranges of other American stoat subspecies) | imperii (Barrett-Hamilton, 1904) microtis (J. A. Allen, 1903) mortigena (Bangs, 1913) |

| Hebrides stoat M. e. ricinae |

Miller, 1907 | The Hebrides | ||

| M. e. salva | Hall, 1944 | |||

| M. e. seclusa | Hall, 1944 | |||

| Baffin Island stoat}} M. e. semplei | Sutton and Hamilton, 1932 | Baffin Island and the adjacent parts of the mainland | labiata (Degerbøl, 1935) | |

| British stoat M. e. stabilis

|

Barrett-Hamilton, 1904 | Larger than mainland European stoats[17] | Great Britain; introduced to New Zealand | |

| M. e. stratori | Merriam, 1896 | |||

| Caucasian stoat M. e. teberdina |

Korneev, 1941 | A small subspecies with a coffee to reddish-tawny summer coat[12] | The northern slope of the middle part of the main Caucasus range | balkarica (Basiev, 1962) |

| Tobolsk stoat M. e. tobolica |

Ognev, 1923 | A large subspecies; it is somewhat larger than aestiva, with long and dense fur.[20] | Western Siberia, eastwards to the Yenisei and Altai Mountains and in Kazakhstan |

Physical description

Build

Skeleton

The stoat has large anal scent glands measuring 8.5 mm × 5 mm (0.33 in × 0.20 in) in males and smaller in females. Scent glands are also present on the cheeks, belly and flanks.[24] Epidermal secretions, which are deposited during body rubbing, are chemically distinct from the products of the anal scent glands, which contain a higher proportion of volatile chemicals. When attacked or being aggressive, the stoat secretes the contents of its anal glands, giving rise to a strong, musky odour produced by several sulphuric compounds. The odour is distinct from that of least weasels.[26]

Fur

A stoat in winter fur

Behaviour

Reproduction and development

Young stoat

Territorial and sheltering behaviour

Stoat nesting in a hollow tree.

The stoat does not dig its own burrows, instead using the burrows and nest chambers of the rodents it kills. The skins and underfur of rodent prey are used to line the nest chamber. The nest chamber is sometimes located in seemingly unsuitable places, such as among logs piled against the walls of houses. The stoat also inhabits old and rotting stumps, under tree roots, in heaps of brushwood, haystacks, in bog hummocks, in the cracks of vacant mud buildings, in rock piles, rock clefts, and even in magpie nests. Males and females typically live apart, but close to each other.[34] Each stoat has several dens dispersed within its range. A single den has several galleries, mainly within 30 cm (12 in) of the surface.[35]

Diet

Stoat killing a European rabbit

Communication

The stoat is a usually silent animal, but can produce a range of sounds similar to those of the least weasel. Kits produce a fine chirping noise. Adults trill excitedly before mating, and indicate submission through quiet trilling, whining and squealing. When nervous, the stoat hisses, and will intersperse this with sharp barks or shrieks and prolonged screeching when aggressive.[26]

Aggressive behaviour in stoats is categorised in these forms:[26]

- Noncontact approach, which is sometimes accompanied by a threat display and vocalisation from the approached animal

- Forward thrust, accompanied by a sharp shriek, which is usually done by stoats defending a nest or retreat site

- Nest occupation, when a stoat appropriates the nesting site of a weaker individual

- Kleptoparasitism, in which a dominant stoat appropriates the kill of a weaker one, usually after a fight

Range and population

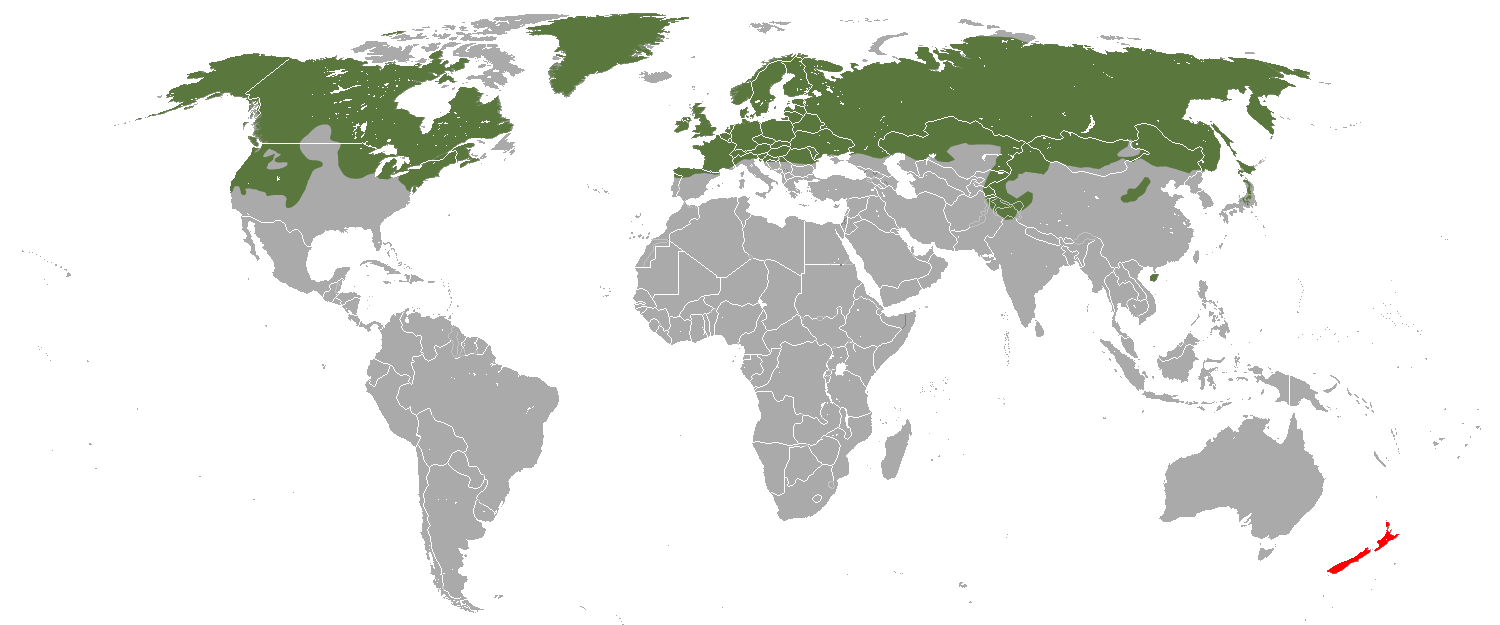

The stoat has a circumboreal range throughout North America, Europe, and Asia, from Greenland and the Canadian and Siberian Arctic islands south to about 35°N. Stoats in North America are found throughout Alaska and Canada south through most of the northern United States to central California, northern Arizona, northern New Mexico, Iowa, the Great Lakes region, New England, and Pennsylvania, but are absent from most of the Great Plains, and the Southeastern United States. The stoat in Europe is found as far south as 41ºN in Portugal, and inhabits most islands with the exception of Iceland, Svalbard, the Mediterranean islands and some small North Atlantic islands. In Japan, it is present in central mountains (northern and central Japan Alps) to northern part of Honshu (primarily above 1,200 m) and Hokkaido. Its vertical range is from sea level to 3,000 m.[1]

Introduction to New Zealand

Stoats were introduced into New Zealand during the late 19th century to control rabbits and hares, but are now a major threat to native bird populations. The introduction of stoats was opposed by scientists in New Zealand and Britain, including the New Zealand ornithologist Walter Buller. The warnings were ignored and stoats began to be introduced from Britain in the 1880s, resulting in a noticeable decline in bird populations within six years.[40] Stoats are a serious threat to ground- and hole-nesting birds, since the latter have very few means of escaping predation. The highest rates of stoat predation occur after seasonal gluts in southern beechmast (beechnuts), which encourage the reproduction of rodents on which stoats also feed, encouraging stoats to increase their own numbers.[41] For instance, the endangered South Island takahē's wild population dropped by a third between 2006 and 2007, after a stoat plague triggered by the 2005–06 mast wiped out more than half the takahē in untrapped areas.[42]Diseases and parasites

Tuberculosis has been recorded in stoats inhabiting the former Soviet Union and New Zealand. They are largely resistant to tularemia, but are reputed to suffer from canine distemper in captivity. Symptoms of mange have also been recorded.[43]Stoats are vulnerable to ectoparasites associated with their prey and the nests of other animals on which they do not prey. The louse Trichodectes erminea is recorded in stoats living in Canada, Ireland and New Zealand. In continental Europe, 26 flea species are recorded to infest stoats, including Rhadinospylla pentacantha, Megabothris rectangulatus, Orchopeas howardi, Spilopsyllus ciniculus, Ctenophthalamus nobilis, Dasypsyllus gallinulae, Nosopsyllus fasciatus, Leptospylla segnis, Ceratophyllus gallinae, Parapsyllus n. nestoris, Amphipsylla kuznetzovi and Ctenopsyllus bidentatus. Tick species known to infest stoats are Ixodes canisuga, I. hexagonus, and I. ricinus and Haemaphysalis longicornis. Louse species known to infest stoats include Mysidea picae and Polyplax spinulosa. Mite species known to infest stoats include Neotrombicula autumnalis, Demodex erminae, Eulaelaps stabulans, Gymnolaelaps annectans, Hypoaspis nidicorva, and Listrophorus mustelae.[43]

The nematode Skrjabingylus nasicola is particularly threatening to stoats, as it erodes the bones of the nasal sinuses and decreases fertility. Other nematode species known to infect stoats include Capillaria putorii, Molineus patens and Strongyloides martes. Cestode species known to infect stoats include Taenia tenuicollis, Mesocestoides lineatus and rarely Acanthocephala.[43]

Relationships with humans

Folklore and mythology

In Irish mythology, stoats were viewed anthropomorphically as animals with families, which held rituals for their dead. They were also viewed as noxious animals prone to thieving, and their saliva was said to be able to poison a grown man. To encounter a stoat when setting out for a journey was considered bad luck, but one could avert this by greeting the stoat as a neighbour.[44] Stoats were also supposed to hold the souls of infants who died before baptism.[45] In the folklore of the Komi people of the Urals, stoats are symbolic of beautiful and coveted young women.[46] In the Zoroastrian religion, the stoat is considered a sacred animal, as its white winter coat represented purity. Similarly, Mary Magdalene was depicted as wearing a white stoat pelt as a sign of her reformed character. One popular European legend had it that a white stoat would die before allowing its pure white coat to be besmirched. When it was being chased by hunters, it would supposedly turn around and give itself up to the hunters rather than risk soiling itself.[47] The former nation (now province) of Brittany in France uses a stylized ermine-fur pattern in forming the Coat of Arms and Flag of Brittany. Gilles Servat's song La blanche Hermine ("The White Ermine") became an anthem for Bretons (and is popular among French people in general).

Ermine were also valued by the Tlingit and other indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. They could be attached to traditional regalia and cedar bark hats as status symbols, or they were also made into shirts.[50]

The stoat was a fundamental item in the fur trade of the Soviet Union, with no less than half the global catch coming from within its borders. The Soviet Union also contained the highest grades of stoat pelts, with the best grade North American pelts being comparable only to the 9th grade in the quality criteria of former Soviet stoat standards. However, stoat harvesting never became a specialty in any Soviet republic, with most stoats being captured incidentally in traps or near villages. Stoats in the Soviet Union were captured either with dogs or with box-traps or jaw-traps. Guns were rarely used, as they could damage the pelt.[51]

Binomial name

Mustela erminea

Stoat range

native introduced

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.