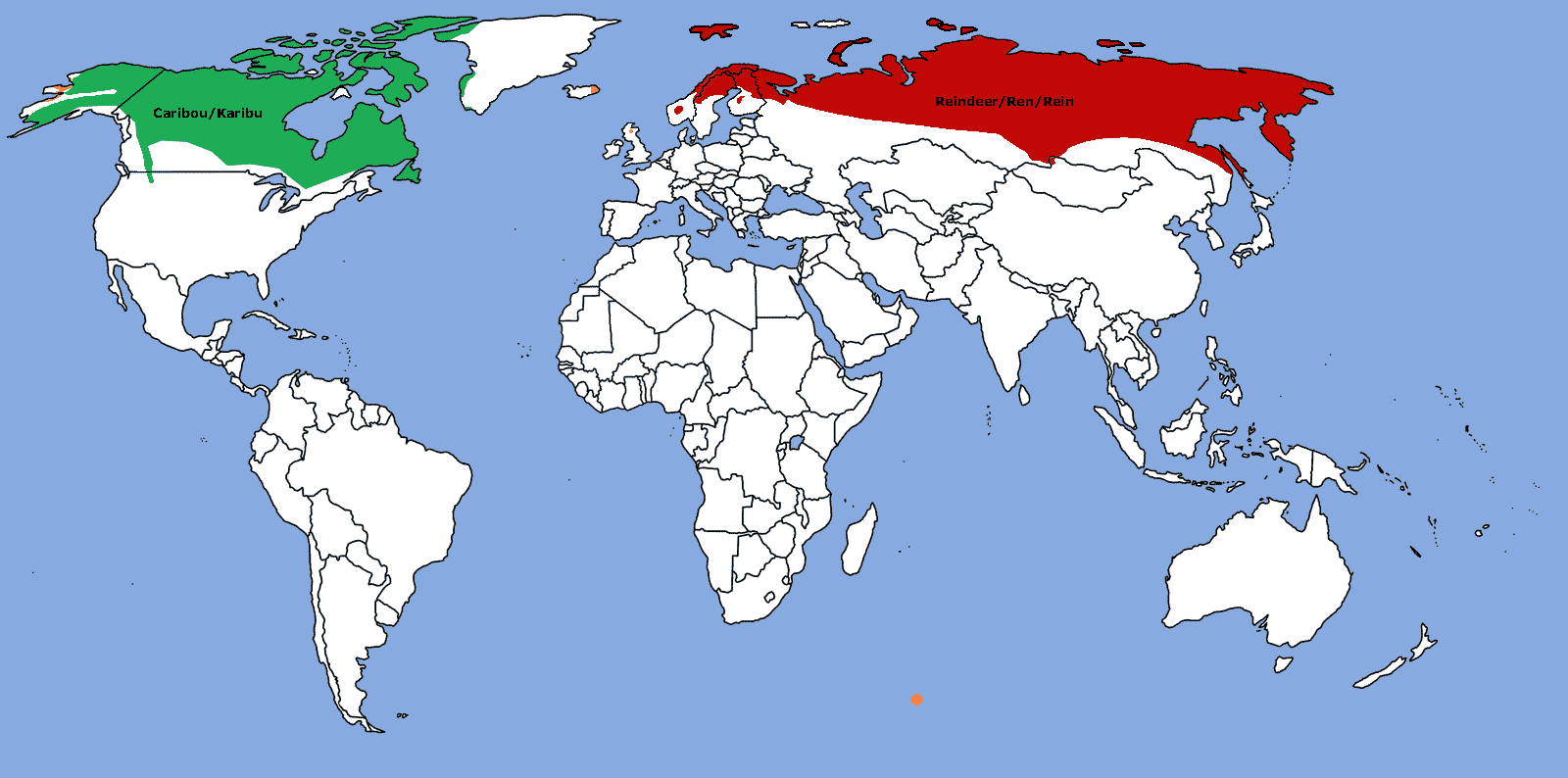

The reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), also known as caribou in North America,[3] is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of northern Europe, Siberia, and North America.[2] This includes both sedentary and migratory populations.

While overall widespread and numerous,[2] some of its subspecies are rare and at least one has already become extinct.[4][5] For this reason, it is considered to be vulnerable by the IUCN.

Reindeer vary considerably in colour and size. Both sexes can grow antlers annually, although the proportion of females that grow antlers varies greatly between population and season.[6] Antlers are typically larger on males.

Hunting of wild reindeer and herding of semi-domesticated reindeer (for meat, hides, antlers, milk and transportation) are important to several Arctic and Subarctic peoples.[7] In Lapland, reindeer pull pulks.[8]

In traditional festive legend, Santa Claus's reindeer pull a sleigh through the night sky to help Santa Claus deliver gifts to children on Christmas Eve.

Description

Status

:focal(2954x2471:2955x2472)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/95/99951bd6-0346-4aae-aed3-6ec51454e16e/istock-579231234.jpg)

The name Rangifer, which Carl Linnaeus chose for the reindeer genus, was used by Albertus Magnus in his De animalibus, fol. Liber 22, Cap. 268: "Dicitur Rangyfer quasi ramifer". This word may go back to a Saami word raingo.[9] For the origin of the word tarandus, which Linnaeus chose as the specific epithet, he made reference to Ulisse Aldrovandi's Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia fol. 859–863, Cap. 30: De Tarando (1621). However, Aldrovandi – and before him Konrad Gesner[10] – thought that rangifer and tarandus were two separate animals.[11] In any case, the tarandos name goes back to Aristotle and Theophrastus – see 'In history' below.

Because of its importance to many cultures, Rangifer tarandus and some of its subspecies have names in many languages. The name rein (-deer) is of Norse origin (Old Norse hreinn, which again goes back to Proto-Germanic *hrainaz and Proto-Indo-European *kroinos meaning "horned animal"). In the Uralic languages, Sami *poatsoj (in Northern Sami boazu, in Lule Sami boatsoj, in Pite Sami båtsoj, in Southern Sami bovtse, in Inari Sami puásui), Meadow Mari pücö and Udmurt pudžej,

all referring to domesticated reindeer, go back to *pocaw, an Iranian

loan word deriving from Proto-Indo-European *peḱu-, meaning "cattle".

The Finnish name poro may also stem from the same.[12]

The word deer was originally broader in meaning, but became more specific over time. In Middle English, der (Old English dēor) meant a wild animal of any kind. This was in contrast to cattle,

which then meant any sort of domestic livestock that was easy to

collect and remove from the land, from the idea of personal-property

ownership (rather than real estate property) and related to modern chattel (property) and capital. Cognates of Old English dēor in other dead Germanic languages have the general sense of animal, such as Old High German tior, Old Norse djúr or dýr, Gothic dius, Old Saxon dier, and Old Frisian diar.[13]

The name caribou comes, through French, from Mi'kmaq qalipu, meaning "snow shoveler", referring to its habit of pawing through the snow for food.[14] In Inuktitut, spoken in eastern Arctic North America, the caribou is known by the name tuktu.[15][16] In the western North American Arctic, the term used by the Iñupiat is tuttu, or tutu.[17]

Taxonomy and evolution

The species taxonomic name Rangifer tarandus was defined by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. The subspecies taxonomic name, Rangifer tarandus caribou was defined by Gmelin in 1788.

Based on Banfield's often-cited A Revision of the Reindeer and Caribou, Genus Rangifer (1961),[18] R. t. caboti (Labrador caribou), R. t. osborni (Osborn's caribou—from British Columbia) and R. t. terraenovae (Newfoundland caribou) were considered invalid and included in R. t. caribou.

Some recent authorities have considered them all valid, even suggesting that they are quite distinct. In their book entitled Mammal Species of the World, American zoologist Don E. Wilson and DeeAnn Reeder agree with Valerius Geist, specialist on large North American mammals, that this range actually includes several subspecies.[19][20][21][Notes 1]

Geist (2007) argued that the "true woodland caribou, the uniformly

dark, small-maned type with the frontally emphasized, flat-beamed

antlers", which is "scattered thinly along the southern rim of North

American caribou distribution" has been incorrectly classified. He

affirms that "true woodland caribou is very rare, in very great

difficulties and requires the most urgent of attention."[19]

In 2005, an analysis of mtDNA

found differences between the caribou from Newfoundland, Labrador,

south-western Canada and south-eastern Canada, but maintained all in R. t caribou.[22]

Mallory and Hillis argued that, "Although the taxonomic designations

reflect evolutionary events, they do not appear to reflect current

ecological conditions. In numerous instances, populations of the same

subspecies have evolved different demographic and behavioural

adaptations, while populations from separate subspecies have evolved

similar demographic and behavioural patterns... "[U]nderstanding ecotype

in relation to existing ecological constraints and releases may be more

important than the taxonomic relationships between populations."[23]

Current classifications of Rangifer tarandus, either with

prevailing taxonomy on subspecies, designations based on ecotypes, and

natural population groupings, fail to capture "the variability of

caribou across their range in Canada" needed for effective species

conservation and management.[24]

"Across the range of a species, individuals may display considerable

morphological, genetic, and behavioural variability reflective of both

plasticity and adaptation to local environments."[25] COSEWIC developed Designated Unit (DU) attribution to add to classifications already in use.[24]

Subspecies

Some of the Rangifer tarandus subspecies may be further divided by ecotype depending on several behavioural factors – predominant habitat use (northern, tundra, mountain, forest, boreal forest, forest-dwelling, woodland, woodland (mountain), woodland (boreal), woodland (migratory), spacing (dispersed or aggregated), and migration (sedentary or migratory).[28][29][30]

The "glacial-interglacial cycles of the upper Pleistocene had a major influence on the evolution" of Rangifer tarandus and other Arctic and sub-Arctic species. Isolation of Rangifer tarandus in refugia during the last glacial – the Wisconsin in North America and the Weichselian in Eurasia-shaped "intraspecific genetic variability" particularly between the North American and Eurasian parts of the Arctic.[3]

In 1986 Kurtén reported that the oldest reindeer fossil was an "antler of tundra reindeer type from the sands of Süssenborn" in the Pleistocene (Günz) period (680,000 to 620,000 BP).[1] By the 4-Würm period (110-70,000 to 12–10,000) its European range was very extensive. Reindeer occurred in

... Spain, Italy and southern Russia. Reindeer [was] particularly abundant in the Magdalenian deposits from the late part of the 4-Wurm just before the end of the Ice Age: at that time and at the early Mesolithic it was the game animal for many tribes. The supply began to get low during the Mesolithic, when reindeers retired to the north."In spite of the great variation, all the Pleistocene and living reindeer belong to the same species."[1]

— Kurtén 1968:170

Humans started hunting reindeer in the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, and humans are today the main predator in many areas. Norway and Greenland have unbroken traditions of hunting wild reindeer from the last glacial period until the present day. In the non-forested mountains of central Norway, such as Jotunheimen, it is still possible to find remains of stone-built trapping pits, guiding fences, and bow rests, built especially for hunting reindeer. These can, with some certainty, be dated to the Migration Period, although it is not unlikely that they have been in use since the Stone Age.[citation needed]

Biology and behaviour

Physical characteristics

The colour of the fur varies considerably, both between individuals and depending on season and subspecies. Northern populations, which usually are relatively small, are whiter, while southern populations, which typically are relatively large, are darker. This can be seen well in North America, where the northernmost subspecies, the Peary caribou, is the whitest and smallest subspecies of the continent, while the southernmost subspecies, the woodland caribou, is the darkest and largest.[32] The coat has two layers of fur: a dense woolly undercoat and longer-haired overcoat consisting of hollow, air-filled hairs.

Like moose, reindeer have specialized noses featuring nasal turbinate bones that dramatically increase the surface area within the nostrils. Incoming cold air is warmed by the animal's body heat before entering the lungs, and water is condensed from the expired air and captured before the deer's breath is exhaled, used to moisten dry incoming air and possibly absorbed into the blood through the mucous membranes.

Reindeer hooves adapt to the season: in the summer, when the tundra is soft and wet, the footpads become sponge-like and provide extra traction. In the winter, the pads shrink and tighten, exposing the rim of the hoof, which cuts into the ice and crusted snow to keep it from slipping. This also enables them to dig down (an activity known as "cratering")[33][34] through the snow to their favorite food, a lichen known as reindeer moss.

The females usually measure 162–205 cm (64–81 in) in length and weigh 80–120 kg (180–260 lb).[35] The males (or "bulls") are typically larger (to an extent which varies between the different subspecies), measuring 180–214 cm (71–84 in) in length and usually weighing 159–182 kg (351–401 lb).[35] Exceptionally large males have weighed as much as 318 kg (701 lb).[35] Shoulder height is typically 85 to 150 cm (33 to 59 in), and the tail is 14 to 20 cm (5.5 to 7.9 in) long. The reindeer from Svalbard are the smallest. They are also relatively short-legged and may have a shoulder height of as little as 80 cm (31 in),[36] thereby following Allen's rule.

The knees of many species of reindeer are adapted to produce a clicking sound as they walk.[37] The sounds originate in the tendons of the knees and may be audible from ten meters away. The frequency of the knee-clicks is one of a range of signals that establish relative positions on a dominance scale among reindeer. "Specifically, loud knee-clicking is discovered to be an honest signal of body size, providing an exceptional example of the potential for non-vocal acoustic communication in mammals."[38]

A study by researchers from University College London in 2011 revealed that reindeer can see light with wavelengths as short as 320 nm (i.e. in the ultraviolet range), considerably below the human threshold of 400 nm. It is thought that this ability helps them to survive in the Arctic, because many objects that blend into the landscape in light visible to humans, such as urine and fur, produce sharp contrasts in ultraviolet.[39] A study at the University of Tromsø has confirmed that "Arctic reindeer eyes change in colour through the seasons from gold through to blue to help them better detect predators...".[40]

Diet

Reproduction and life-cycle

Mating occurs from late September to early November. Males battle for access to females. Two males will lock each other's antlers together and try to push each other away. The most dominant males can collect as many as 15–20 females to mate with. A male will stop eating during this time and lose much of his body reserves.[46]Calves may be born the following May or June. After 45 days, the calves are able to graze and forage but continue suckling until the following autumn when they become independent from their mothers.[46]

Social structure, migration and range

Normally travelling about 19–55 km (12–34 mi) a day while migrating, the caribou can run at speeds of 60–80 km/h (37–50 mph).[2] Young caribou can already outrun an Olympic sprinter when only a day old.[51] During the spring migration smaller herds will group together to form larger herds of 50,000 to 500,000 animals, but during autumn migrations the groups become smaller, and the reindeer begin to mate. During winter, reindeer travel to forested areas to forage under the snow. By spring, groups leave their winter grounds to go to the calving grounds. A reindeer can swim easily and quickly, normally at about 6.5 km/h (4 mph) but if necessary at 10 km/h (6 mph), and migrating herds will not hesitate to swim across a large lake or broad river.[2]

As an adaptation to their Arctic environment, they have lost their circadian rhythm.[52]

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

%20NPS%20Jay%20Elhard.jpg?crop=7%2C0%2C3340%2C2088&wid=1640&hei=1025&scl=2.0370731707317074)

Originally, the reindeer was found in Scandinavia, eastern Europe, Greenland, Russia, Mongolia, and northern China north of the 50th latitude. In North America, it was found in Canada, Alaska, and the northern conterminous USA from Washington to Maine. In the 19th century, it was apparently still present in southern Idaho.[2] Even in historical times, it probably occurred naturally in Ireland. During the late Pleistocene era, reindeer occurred as far south as Nevada and Tennessee in North America, and as far south as Spain in Europe.[47][53]

Today, wild reindeer have disappeared from these areas, especially from

the southern parts, where it vanished almost everywhere. Large

populations of wild reindeer are still found in Norway, Finland, Siberia, Greenland, Alaska, and Canada.

According to the Grubb (2005), Rangifer tarandus is

"circumboreal in the tundra and taiga" from "Svalbard, Norway, Finland,

Russia, Alaska (USA) and Canada including most Arctic islands, and

Greenland, south to northern Mongolia, China (Inner Mongolia; now only domesticated or feral?), Sakhalin Island, and USA (Northern Idaho and the Great Lakes region). Reindeer were introduced to, and feral in, Iceland, Kerguelen Islands, South Georgia Island, Pribilof Islands, St. Matthew Island."[26]

There is strong regional variation in Rangifer herd size.

There are large population differences among individual herds, and the

size of individual herds has varied greatly since 1970. The largest of

all herds (Taimyr, Russia) has varied between 400,000 and 1,000,000; the

second largest herd (George River, Canada) has varied between 28,000

and 385,000.

While Rangifer is a widespread and numerous genus in the northern Holarctic, being present in both tundra and taiga (boreal forest),[47] by 2013, many herds had "unusually low numbers" and their winter ranges in particular were smaller than they used to be.[54] Caribou and reindeer numbers have fluctuated historically, but many herds are in decline across their range.[55] This global decline is linked to climate change for northern, migratory herds and industrial disturbance of habitat for non-migratory herds.[56]

In November 2016, it was reported that more than 81,000 reindeer in

Russia had died as a result of climate change. Longer autumns leading to

increased amounts of freezing rain created a few inches of ice over lichen, starving many reindeer.[57]

Predators

As carrion, reindeer are fed on opportunistically by foxes, hawks, and ravens. Blood-sucking insects, such as black flies and mosquitoes, are a plague to reindeer during the summer and can cause enough stress to inhibit feeding and calving behaviours.[59] An adult reindeer will lose perhaps about 1 liter (about 2 US pints) of blood to biting insects for every week it spends in the tundra.[51] The population numbers of some of these predators is influenced by the migration of reindeer.[citation needed]

In one case, the entire body of a reindeer was found in the stomach of a Greenland shark, a species found in the far northern Atlantic, although this was possibly a case of scavenging, considering the dissimilarity of habitats between the ungulate and the large, slow-moving fish.[60]

Rangifer tarandus by country

Russia

In

2013, the Taimyr herd in Russia was the largest herd in the world. In

2000, the herd increased to 1,000,000 but by 2009, there were 700,000

animals.[54][61] In the 1950s, there were 110,000.[62]

There are three large herds of migratory tundra wild reindeer in

central Siberia's Yakutia region: Lena-Olenek, Yana-Indigirka and

Sundrun herds. While the population of the Lena-Olenek herd is stable,

the others are declining.[62]

Further east again, the Chukotka herd is also in decline. In 1971,

there were 587,000 animals. They recovered after a severe decline in

1986, to only 32,200 individuals, but their numbers fell again.[63] According to Kolpashikov, by 2009 there were less than 70,000.[62]

North America

In North America, because of its vast range in a wide diversity of ecosystems, the subspecies Rangifer tarandus caribou is further distinguished by a number of ecotypes, including boreal woodland caribou, mountain woodland caribou and migratory woodland caribou).[28][29][30] Populations—caribou that do not migrate—or herds—those that do migrate—may not fit into narrow ecotypes. For example, Banfield's 1961 classification of the migratory George River Caribou Herd, in the Ungava region of Quebec, as subspecies Rangifer tarandus caribou, woodland caribou, remains—although other woodland caribou are mainly sedentary.

Rangifer tarandus is "endangered in Canada in regions such as south-east British Columbia at the Canadian-USA border, along the Columbia, Kootenay and Kootenai rivers and around Kootenay Lake. Rangifer tarandus is endangered in the United States in Idaho and Washington. R. t. pearyi is on the IUCN endangered list." According to Geist, the "woodland caribou is highly endangered throughout its distribution right into Ontario."[26]

United States

Although there are remnant populations of R. t. caribou boreal woodland caribou

in the northern United States, most of U.S. caribou populations are in

Alaska. There are four herds in Alaska, the Western Arctic herd,

Teshekpuk Lake herd, the Central Arctic herd and the Porcupine herd.

The Western Arctic Caribou Herd

is the largest of the three. The Western Arctic herd reached a low of

75,000 in the mid-1970s. In 1997 the 90,000 WACH changed their migration

and wintered on Seward Peninsula.

Alaska's reindeer herding industry has been concentrated on Seward

Peninsula ever since the first shipment of reindeer was imported from

eastern Siberia in 1892 as part of the Reindeer Project, an initiative

to replace whale meat in the diet of the indigenous people of the

region.[64]

For many years it was believed that the geography of the peninsula

would prevent migrating caribou from mingling with domesticated reindeer

who might otherwise join caribou herds when they left an area.[64][65] However, in 1997 the domesticated reindeer joined the Western Arctic Caribou Herd on their summer migration and disappeared.[66] The WACH reached a peak of 490,000 in 2003 and then declined to 325,000 in 2011.[35][67]

In 2008, the Teshekpuk Lake herd had 64,107 animals and the Central Arctic herd had 67,000.[68][69]

Migratory caribou herds are named after their birthing grounds, in this case the Porcupine River, which runs through a large part of the range of the Porcupine herd. Though numbers fluctuate, the herd comprises approximately 169,000 animals (based on a July 2010 photocensus).[35] 2,500 km (1,600 mi) a year land migration between their winter range and calving grounds on the Beaufort Sea, is the longest of any land mammal on earth. They are the traditional food of the Gwich'in, a First Nations/Alaska Native people, the Inupiat, Inuvialuit, Hän, and Northern Tutchone. There is currently controversy over whether possible future oil drilling on the coastal plains of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, encompassing much of the Porcupine caribou calving grounds, will have a severe negative impact on the caribou population or whether the caribou population will grow.

Unlike many other Rangifer tarandus subspecies and their ecotypes, the Porcupine herd is stable at relatively high numbers, but the 2013 photo-census was not counted by January 2014.[62] The peak population in 1989 of 178,000 animals was followed by a decline by 2001 to 123,000. However, by 2010, there was a recovery and an increase to 169,000 animals.[62][70]

Canada

The barren-ground caribou subspecies R. t. groenlandicus,,[18]

a long-distance migrant, includes large herds in the Northwest

Territories and in Nunavut, for example the Beverly, the Ahiak and

Qamanirjuaq herds. In 1996, the population of the Ahiak herd was

approximately 250,000 animals.

Ahiak, Beverly, Qamanirjuaq herds

The Ahiak, Beverly, Qamanirjuaq herds are barren-ground caribou.The barren-ground caribou population on Southampton Island, Nunavut declined by almost 75%, from about 30,000 caribou in 1997 to 7,800 caribou in 2011.[62][79]

Peary caribou on Baffin Island

Northwest Territories

There are four barren-ground caribou herds in the Northwest Territories—Cape Bathurst, Bluenose West, Bluenose East and Bathurst.[62] The Bluenose East caribou herd began a recovery with a population of approximately 122,000 in 2010.[82] which is being credited to the establishment of Tuktut Nogait National Park.[83] According to T. Davison 2010, CARMA 2011, the three other herds "declined 84–93% from peak sizes in the mid-1980s and 1990s.[62]

R. t. caribou

The subspecies R. t. caribou commonly known as woodland caribou, is divided into ecotypes: boreal woodland caribou (also known as forest-dwelling), woodland caribou (boreal), mountain woodland caribou, and migratory woodland caribou.[clarification needed]

Caribou are classified by ecotype depending on several behavioural

factors – predominant habitat use (northern, tundra, mountain, forest,

boreal forest, forest-dwelling), spacing (dispersed or aggregated) and

migration (sedentary or migratory).[28][29][30]

In Canada, the national meta-population of the sedentary boreal ecotype spans the boreal forest from the Northwest Territories to Labrador. They prefer lichen-rich mature forests[84] and mainly live in marshes, bogs, lakes, and river regions.[85][86] The historic range of the boreal woodland caribou covered over half of present-day Canada,[87] stretching from Alaska to Newfoundland and Labrador and as far south as New England,

Idaho, and Washington. Woodland caribou have disappeared from most of

their original southern range. The boreal woodland was designated as threatened in 2002.[88] In 2011 there were approximately 34,000 boreal caribou in 51 ranges remaining in Canada.[89]

George River caribou herd (GRCH)

The migratory George River caribou herd (GRCH), in the Ungava region of Quebec and Labrador in eastern Canada was once the world's largest herd with 800,000–900,000 animals. Although it is categorized as a subspecies Rangifer tarandus caribou,[18] the woodland caribou, the GRCH is migratory woodland caribou and like the barren-ground caribou it's ecotype may be tundra caribou, Arctic, northern of migratory, not forest-dwelling and sedentary like most woodland caribou ecotypes. It is unlike most woodland caribou in that it is not sedentary. Since the mid-1990s, the herd declined sharply and by 2010, it was reduced to 74,131—a drop of up to 92%.[90] A 2011 survey confirms a continuing decline of the George River migratory caribou herd population. By 2012 it was estimated to be about 27,600 animals, down from 385,000 in 2001 and 74,131 in 2010."[54][90][91]Leaf River caribou herd (LRCH)

The Leaf River caribou herd

(LRCH),[92] another migratory forest-tundra ecotype of the boreal woodland caribou, near the coast of Hudson Bay, increased from 270 000 individuals in 1991 to 628 000 in 2001.[93] By 2011 the herd had decreased to 430 000 caribou.[54][90][94]

According to an international study on caribou populations, the George

River and Leaf River herds, and other herds that migrate from Nunavik,

Quebec and insular Newfoundland, could be threatened with extinction by

2080.[91]

Queen Charlotte Islands caribou

The Queen Charlotte Islands caribou (R. tarandus dawsoni) from the Queen Charlotte Islands was believed to represent a distinct subspecies. It became extinct at the beginning of the 20th century. However, recent DNA analysis from mitochondrial DNA

of the remains from those reindeer suggest that the animals from the

Queen Charlotte Islands were not genetically distinct from the Canadian

mainland reindeer subspecies.[5]

Greenland

According to Kolpashikov et al. (2013) there were four main populations of wild R. t. groenlandicus, barren-ground caribou, in west Greenland in 2013.[62] The Kangerlussuaq-Sisimiut caribou herd, the largest had a population of around 98,000 animals in 2007.[62][95]

The "second largest, Akia-Maniitsoq decreased from an estimated 46,000

in 2001 to about 17,400 in 2010. According to Cuyler, "one possible

cause might be the topography, which prevents hunter access in the

former while permitting access in the latter."[62]

Norway

The last remaining wild tundra reindeer in Europe are found in portions of southern Norway.[96]

In southern Norway in the mountain ranges, there are about

30,000–35,000 reindeer with 23 different populations. The largest herd

with about 10,000 individuals, is at Hardangervidda. By 2013 the

greatest challenges to management were "loss of habitat and migration

corridors to piecemeal infrastructure development and abandonment of

reindeer habitat as a result of human activities and disturbance."[54]

Norway is now preparing to apply for nomination as a World Heritage Site for areas with traces and traditions of reindeer hunting in Dovrefjell-Sunndalsfjella National Park, Reinheimen National Park and Rondane National Park in Central Sør-Norge (Southern Norway). There is in these parts of Norway an unbroken tradition of reindeer hunting from post-glacial Stone Age until today.[citation needed]

On 29 August 2016, the Norwegian Environment Agency announced the death of 323 reindeer by the effects of a lightning strike in Hardangervidda.[97]

Svalbard reindeer

Finland

The Finnish forest reindeer (R. tarandus fennicus), is found in the wild in only two areas of the Fennoscandia peninsula of Northern Europe, in Finnish/Russian Karelia, and a small population in central south Finland. The Karelia population reaches far into Russia, however, so far that it remains an open question whether reindeer further to the east are R. t. fennicus as well.[citation needed] By 2007 reindeer experts were concerned about the collapse of the wild Finnish forest reindeer (Rangifer tarandus fennicus) in the eastern province of Kainuu.[99] During the peak year of 2001, the Finnish forest reindeer population in Kainuu was established at 1,700. In a March 2007 helicopter count, only 960 individuals were detected.Iceland

East Iceland has a small herd of about 2500–3000 animals.[100] Iceland (increasing or are stable at high numbers 2013) Iceland: Reindeer were introduced to Iceland (17) in the late 1700s[101] cited in.[54]

The Icelandic reindeer population in July 2013 was estimated at

approximately 6000. With a hunting quota of 1,229 animals, the winter

2013–2014 population is expected to be around 4800 reindeer[54]

British overseas territory experiment

French overseas territory experiment

Around 4000 reindeer have been introduced into the French sub-Antarctic archipelago of Kerguelen Islands.

Conservation status

While overall widespread and numerous, some subspecies are rare and at least one has already gone extinct.[4][5] As of 2015, the IUCN has classified the reindeer as Vulnerable due to an observed population decline of 40% over the last ~25 years.[2]

Reindeer and humans

Reindeer meat is popular in the Scandinavian countries. Reindeer meatballs are sold canned. Sautéed reindeer is the best-known dish in Lapland. In Alaska and Finland, reindeer sausage is sold in supermarkets and grocery stores. Reindeer meat is very tender and lean. It can be prepared fresh, but also dried, salted, hot- and cold-smoked. In addition to meat, almost all internal organs of reindeer can be eaten, some being traditional dishes.[104] Furthermore, Lapin Poron liha, fresh reindeer meat completely produced and packed in Finnish Lapland, is protected in Europe with PDO classification.[105][106]

Reindeer antler is powdered and sold as an aphrodisiac, nutritional or medicinal supplement to Asian markets.

Caribou have been a major source of subsistence for Canadian Inuit.

Reindeer hunting by humans has a very long history, and caribou/wild reindeer "may well be the species of single greatest importance in the entire anthropological literature on hunting."[7]

Wild caribou are still hunted in North America and Greenland. In the traditional lifestyle of the Inuit people, Northern First Nations people, Alaska Natives, and the Kalaallit of Greenland, the caribou is an important source of food, clothing, shelter, and tools. Many Gwich'in people, who depend on the Porcupine caribou, still follow traditional caribou management practices that include a prohibition against selling caribou meat and limits on the number of caribou to be taken per hunting trip.[107]

The blood of the caribou was supposedly mixed with alcohol as drink by hunters and loggers in colonial Quebec to counter the cold. This drink is now enjoyed without the blood as a wine and whiskey drink known as Caribou.[108][109]

Reindeer husbandry

There are only two genetically pure populations of wild caribous in Northern Europe: wild mountain reindeer (Rangifer tarandus ssp. tarandus) live in central Norway, with a population in 2007 of between 6,000 and 8,400 animals;[110] and wild forest reindeer (Rangifer tarandus ssp. fennicus), in central and eastern Finland and in Russian Karelia, with a population of about 4,350, plus 1,500 in Arkhangelsk and 2,500 in Komi.[111]

DNA analysis indicates that reindeer were independently domesticated in Fennoscandia and Western Russia (and possibly Eastern Russia).[112] Reindeer have been herded for centuries by several Arctic and Subarctic people including the Sami and the Nenets. They are raised for their meat, hides, and antlers and, to a lesser extent, for milk and transportation. Reindeer are not considered fully domesticated, as they generally roam free on pasture grounds. In traditional nomadic herding, reindeer herders migrate with their herds between coast and inland areas according to an annual migration route and herds are keenly tended. However, reindeer were not bred in captivity, though they were tamed for milking as well as for use as draught animals or beasts of burden.[citation needed] Domesticated reindeer are shorter-legged and heavier than their wild counterparts.[citation needed]

The use of reindeer for transportation is common among the nomadic peoples of northern Russia (but not in Scandinavia). Although a sled drawn by 20 reindeer will cover no more than 20–25 km a day (compared to 7–10 km on foot, 70–80 km by a dog sled loaded with cargo, and 150–180 km by a dog sled without cargo), it has the advantage that the reindeer will discover their own food, while a pack of 5–7 sled dogs requires 10–14 kg of fresh fish a day.[113]

The use of reindeer as semi-domesticated livestock in Alaska was introduced in the late 19th century by the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, with assistance from Sheldon Jackson, as a means of providing a livelihood for Native peoples there.[114] Reindeer were imported first from Siberia, and later also from Norway. A regular mail run in Wales, Alaska, used a sleigh drawn by reindeer.[115] In Alaska, reindeer herders use satellite telemetry to track their herds, using online maps and databases to chart the herd's progress.[citation needed]

Domesticated reindeer are mostly found in northern Fennoscandia and Russia, with a herd of approximately 150–170 reindeer living around the Cairngorms region in Scotland. The last remaining wild tundra reindeer in Europe are found in portions of southern Norway.[96] The International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry (ICR), a circumpolar organization, was established in 2005 by the Norwegian government. ICR represents over 20 indigenous reindeer peoples and about 100,000 reindeer herders in 9 different national states.[116] In Finland, there are about 6,000 reindeer herders, most of whom keep small herds of less than 50 reindeer to raise additional income. With 185,000 reindeer (2001), the industry produces 2,000 tons of reindeer meat and generates 35 million euros annually. 70% of the meat is sold to slaughterhouses. Reindeer herders are eligible for national and EU agricultural subsidies, which constituted 15% of their income. Reindeer herding is of central importance for the local economies of small communities in sparsely populated rural Lapland.[117]

Currently, many reindeer herders are heavily dependent on diesel fuel to provide for electric generators and snowmobile transportation, although solar photovoltaic systems can be used to reduce diesel dependency.[118]

In history

Both Aristotle and Theophrastus have short accounts – probably based on the same source – of an ox-sized deer species, named tarandos, living in the land of the Bodines in Scythia,

which was able to change the colour of its fur to obtain camouflage.

The latter is probably a misunderstanding of the seasonal change in

reindeer fur colour. The descriptions have been interpreted as being of

reindeer living in the southern Ural Mountains in c. 350 BC[9]

There is an ox shaped like a stag. In the middle of its forehead a single horn grows between its ears, taller and straighter than the animal horns with which we are familiar. At the top this horn spreads out like the palm of a hand or the branches of a tree. The females are of the same form as the males, and their horns are the same shape and size.According to Olaus Magnus's Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus – printed in Rome in 1555 – Gustav I of Sweden sent 10 reindeer to Albert I, Duke of Prussia, in the year 1533. It may be these animals that Conrad Gessner had seen or heard of.

During World War II, the Soviet Army used reindeer as pack animals to transport food, ammunition and post from Murmansk to the Karelian front and bring wounded soldiers, pilots and equipment back to the base. About 6,000 reindeer and more than 1,000 reindeer herders were part of the operation. Most herders were Nenets, who were mobilized from the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, but reindeer herders from Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Komi also participated.[120][121]

Santa Claus' reindeer

Heraldry and symbols

Several Norwegian municipalities have one or more reindeer depicted in their coats-of-arms: Eidfjord, Porsanger, Rendalen, Tromsø, Vadsø, and Vågå. The historic province of Västerbotten in Sweden has a reindeer in its coat of arms. The present Västerbotten County has very different borders and uses the reindeer combined with other symbols in its coat-of-arms. The city of Piteå also has a reindeer. The logo for Umeå University features three reindeer.[125]

The Canadian 25-cent coin, or "quarter" features a depiction of a caribou on one face. The caribou is the official provincial animal of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, and appears on the coat of arms of Nunavut. A caribou statue was erected at the center of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial, marking the spot in France where hundreds of soldiers from Newfoundland were killed and wounded in the First World War and there is a replica in Bowring Park, in St. John's, Newfoundland's capital city.[citation needed]

Two municipalities in Finland have reindeer motifs in their coats-of-arms: Kuusamo[126] has a running reindeer and Inari[127] a fish with reindeer antlers.

/--/uploads/2024/02/IH4A1837-1-e1708950084801.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/reindeers-on-a-farm--hetta--enontekioe--finland-1251778560-25c3fca2aad34355903b2b9283cd7c60.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.