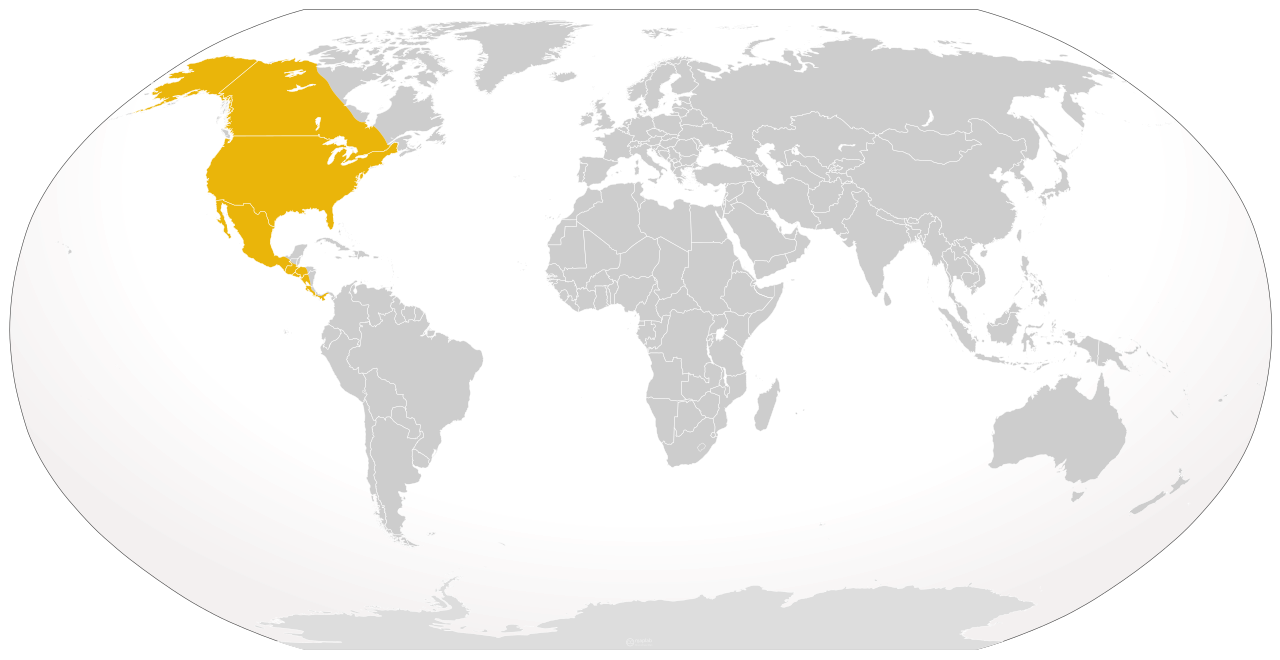

The coyote is listed as least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, due to its wide distribution and abundance throughout North America, southwards through Mexico and into Central America. The species is versatile, able to adapt to and expand into environments modified by humans. It is enlarging its range, with coyotes moving into urban areas in the eastern U.S., and was sighted in eastern Panama (across the Panama Canal from their home range) for the first time in 2013.

The coyote has 19 recognized subspecies. The average male weighs 8 to 20 kg (18 to 44 lb) and the average female 7 to 18 kg (15 to 40 lb). Their fur color is predominantly light gray and red or fulvous interspersed with black and white, though it varies somewhat with geography. It is highly flexible in social organization, living either in a family unit or in loosely knit packs of unrelated individuals. Primarily carnivorous, its diet consists mainly of deer, rabbits, hares, rodents, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, though it may also eat fruits and vegetables on occasion. Its characteristic vocalization is a howl made by solitary individuals. Humans are the coyote's greatest threat, followed by cougars and gray wolves. In spite of this, coyotes sometimes mate with gray, eastern, or red wolves, producing "coywolf" hybrids. In the northeastern regions of North America, the eastern coyote (a larger subspecies, though still smaller than wolves) is the result of various historical and recent matings with various types of wolves. Genetic studies show that most North American wolves contain some level of coyote DNA.

The coyote is a prominent character in Native American folklore, mainly in Aridoamerica, usually depicted as a trickster that alternately assumes the form of an actual coyote or a man. As with other trickster figures, the coyote uses deception and humor to rebel against social conventions. The animal was especially respected in Mesoamerican cosmology as a symbol of military might. After the European colonization of the Americas, it was seen in Anglo-American culture as a cowardly and untrustworthy animal. Unlike wolves (gray, eastern, or red), which have undergone an improvement of their public image, attitudes towards the coyote remain largely negative.

Description

Closeup of a mountain coyote's (C. l. lestes) head

The color and texture of the coyote's fur varies somewhat geographically.[5] The hair's predominant color is light gray and red or fulvous, interspersed around the body with black and white. Coyotes living at high elevations tend to have more black and gray shades than their desert-dwelling counterparts, which are more fulvous or whitish-gray.[8] The coyote's fur consists of short, soft underfur and long, coarse guard hairs. The fur of northern subspecies is longer and denser than in southern forms, with the fur of some Mexican and Central American forms being almost hispid (bristly).[9] Generally, adult coyotes (including coywolf hybrids) have a sable coat color, dark neonatal coat color, bushy tail with an active supracaudal gland, and a white facial mask.[10] Albinism is extremely rare in coyotes; out of a total of 750,000 coyotes killed by federal and cooperative hunters between March 22, 1938, and June 30, 1945, only two were albinos.[8]

The coyote is typically smaller than the gray wolf, but has longer ears and a relatively larger braincase,[5] as well as a thinner frame, face, and muzzle. The scent glands are smaller than the gray wolf's, but are the same color.[7] Its fur color variation is much less varied than that of a wolf.[11] The coyote also carries its tail downwards when running or walking, rather than horizontally as the wolf does.[12]

Coyote tracks can be distinguished from those of dogs by their more elongated, less rounded shape.[13][14] Unlike dogs, the upper canines of coyotes extend past the mental foramina.[5]

Taxonomy and evolution

History

Toltec pictograph of a coyote

The small wolf or burrowing dog of the prairies are the inhabitants almost invariably of the open plains; they usually associate in bands of ten or twelve sometimes more and burrow near some pass or place much frequented by game; not being able alone to take deer or goat they are rarely ever found alone but hunt in bands; they frequently watch and seize their prey near their burrows; in these burrows they raise their young and to them they also resort when pursued; when a person approaches them they frequently bark, their note being precisely that of the small dog. They are of an intermediate size between that of the fox and dog, very active fleet and delicately formed; the ears large erect and pointed the head long and pointed more like that of the fox; tale long ... the hair and fur also resembles the fox, tho' is much coarser and inferior. They are of a pale redish-brown colour. The eye of a deep sea green colour small and piercing. Their [claws] are reather longer than those of the ordinary wolf or that common to the Atlantic states, none of which are to be found in this quarter, nor I believe above the river Plat.[17]The coyote was first scientifically described by naturalist Thomas Say in September 1819, on the site of Lewis and Clark's Council Bluffs, 24 km (15 mi) up the Missouri River from the mouth of the Platte during a government-sponsored expedition with Major Stephen Long. He had the first edition of the Lewis and Clark journals in hand, which contained Biddle's edited version of Lewis's observations dated 5 May 1805. His account was published in 1823. Say was the first person to document the difference between a "prairie wolf" (coyote) and on the next page of his journal a wolf which he named Canis nubilus (Great Plains wolf).[3][18] Say described the coyote as:

Canis latrans. Cinereous or gray, varied with black above, and dull fulvous, or cinnamon; hair at base dusky plumbeous, in the middle of its length dull cinnamon, and at tip gray or black, longer on the vertebral line; ears erect, rounded at tip, cinnamon behind, the hair dark plumbeous at base, inside lined with gray hair; eyelids edged with black, superior eyelashes black beneath, and at tip above; supplemental lid margined with black-brown before, and edged with black brown behind; iris yellow; pupil black-blue; spot upon the lachrymal sac black-brown; rostrum cinnamon, tinctured with grayish on the nose; lips white, edged with black, three series of black seta; head between the ears intermixed with gray, and dull cinnamon, hairs dusky plumbeous at base; sides paler than the back, obsoletely fasciate with black above the legs; legs cinnamon on the outer side, more distinct on the posterior hair: a dilated black abbreviated line on the anterior ones near the wrist; tail bushy, fusiform, straight, varied with gray and cinnamon, a spot near the base above, and tip black; the tip of the trunk of the tail, attains the tip of the os calcis, when the leg is extended; beneath white, immaculate, tail cinnamon towards the tip, tip black; posterior feet four toed, anterior five toed.[3]

Naming and etymology

The earliest written reference to the species comes from the naturalist Francisco Hernández's Plantas y Animales de la Nueva España (1651), where it is described as a "Spanish fox" or "jackal". The first published usage of the word "coyote" (which is a Spanish borrowing of its Nahuatl name coyōtl

- Local and indigenous names for Canis latrans

Evolution

| Phylogenetic tree of the extant wolf-like canids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationships between the extant wolf-like canids based on DNA taken from the cell nucleus,[40][41] except for the Himalayan wolf (Canis lupus filchneri) that is based on mitochondrial DNA sequences[41][42] plus X chromosome and Y chromosome sequences.[42] Timing in millions of years.[41] |

Fossil record

Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford, one of the foremost authorities on carnivore evolution,[43] proposed that the genus Canis was the descendant of the coyote-like Eucyon davisi and its remains first appeared in the Miocene 6 million years ago (Mya) in the southwestern US and Mexico. By the Pliocene (5 Mya), the larger Canis lepophagus[44] appeared in the same region and by the early Pleistocene (1 Mya) C. latrans (the coyote) was in existence. They proposed that the progression from Eucyon davisi to C lepophagus to the coyote was linear evolution.[45]:p58 Additionally, C. latrans and C. aureus are closely related to C. edwardii, a species that appeared earliest spanning the mid-Blancan (late Pliocene) to the close of the Irvingtonian (late Pleistocene), and coyote remains indistinguishable from C. latrans were contemporaneous with C. edwardii in North America.[1]:p175,180 Johnston describes C. lepophagus as having a more slender skull and skeleton than the modern coyote.[46]:385 Ronald Nowak found that the early populations had small, delicate, narrowly proportioned skulls that resemble small coyotes and appear to be ancestral to C. latrans.[47]:p241

C. lepophagus was similar in weight to modern coyotes, but had shorter limb bones that indicates a less cursorial lifestyle. The coyote represents a more primitive form of Canis than the gray wolf, as shown by its relatively small size and its comparatively narrow skull and jaws, which lack the grasping power necessary to hold the large prey in which wolves specialize. This is further corroborated by the coyote's sagittal crest, which is low or totally flattened, thus indicating a weaker bite than the wolf's. The coyote is not a specialized carnivore as the wolf is, as shown by the larger chewing surfaces on the molars, reflecting the species' relative dependence on vegetable matter. In these respects, the coyote resembles the fox-like progenitors of the genus more so than the wolf.[48]

The oldest fossils that fall within the range of the modern coyote date to 0.74–0.85 Ma (million years) in Hamilton Cave, West Virginia; 0.73 Ma in Irvington, California; 0.35–0.48 Ma in Porcupine Cave, Colorado and in Cumberland Cave, Pennsylvania.[1]:p136 Modern coyotes arose 1,000 years after the Quaternary extinction event.[49] Compared to their modern Holocene counterparts, Pleistocene coyotes (C. l. orcutti) were larger and more robust, likely in response to larger competitors and prey.[49] Pleistocene coyotes were likely more specialized carnivores than their descendants, as their teeth were more adapted to shearing meat, showing fewer grinding surfaces suited for processing vegetation.[50] Their reduction in size occurred within 1000 years of the Quaternary extinction event, when their large prey died out.[49] Furthermore, Pleistocene coyotes were unable to exploit the big-game hunting niche left vacant after the extinction of the dire wolf (C. dirus), as it was rapidly filled by gray wolves, which likely actively killed off the large coyotes, with natural selection favoring the modern gracile morph.[50]

DNA evidence

In 1993, a study proposed that the wolves of North America display skull traits more similar to the coyote than wolves from Eurasia.[51] In 2010, a study found that the coyote was a basal member of the clade that included the Tibetan wolf, the domestic dog, the Mongolian wolf and the Eurasian wolf, with the Tibetan wolf diverging early from wolves and domestic dogs.[52] In 2016, a whole-genome DNA study proposed, based on the assumptions made, that all of the North American wolves and coyotes diverged from a common ancestor less than 6,000–117,000 years ago. The study also indicated that all North American wolves have a significant amount of coyote ancestry and all coyotes some degree of wolf ancestry, and that the red wolf and eastern wolf are highly admixed with different proportions of gray wolf and coyote ancestry.[53][54] The proposed timing of the wolf/coyote divergence conflicts with the finding of a coyote-like specimen in strata dated to 1 Mya.[45]

Genetic studies relating to wolves or dogs have inferred phylogenetic relationships based on the only reference genome available, that of the Boxer dog. In 2017, the first reference genome of the wolf Canis lupus lupus was mapped to aid future research.[55] In 2018, a study looked at the genomic structure and admixture of North American wolves, wolf-like canids, and coyotes using specimens from across their entire range that mapped the largest dataset of nuclear genome sequences against the wolf reference genome. The study supports the findings of previous studies that North American gray wolves and wolf-like canids were the result of complex gray wolf and coyote mixing. A polar wolf from Greenland and a coyote from Mexico represented the purest specimens. The coyotes from Alaska, California, Alabama, and Quebec show almost no wolf ancestry. Coyotes from Missouri, Illinois, and Florida exhibit 5–10% wolf ancestry. There was 40%:60% wolf to coyote ancestry in red wolves, 60%:40% in Eastern timber wolves, and 75%:25% in the Great Lakes wolves. There was 10% coyote ancestry in Mexican wolves and the Atlantic Coast wolves, 5% in Pacific Coast and Yellowstone wolves, and less than 3% in Canadian archipelago wolves. If a third canid had been involved in the admixture of the North American wolf-like canids then its genetic signature would have been found in coyotes and wolves, which it has not.[56]

In 2018, whole genome sequencing was used to compare members of genus Canis. The study indicates that the common ancestor of the coyote and gray wolf has genetically admixed with a ghost population of an extinct unidentified canid. The canid was genetically close to the dhole and had evolved after the divergence of the African wild dog from the other canid species. The basal position of the coyote compared to the wolf is proposed to be due to the coyote retaining more of the mitochondrial genome of this unknown canid.[57]

Subspecies

As of 2005, 19 subspecies are recognized.[23][58] Geographic variation in coyotes is not great, though taken as a whole, the eastern subspecies (C. l. thamnos and C. l. frustor) are large, dark-colored animals, with a gradual paling in color and reduction in size westward and northward (C. l. texensis, C. l. latrans, C. l. lestes, and C. l. incolatus), a brightening of ochraceous tones–deep orange or brown–towards the Pacific coast (C. l. ochropus, C. l. umpquensis), a reduction in size in Aridoamerica (C. l. microdon, C. l. mearnsi) and a general trend towards dark reddish colors and short muzzles in Mexican and Central American populations.[59]

| Subspecies | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms | Image |

|---|

Hybridization

Melanistic coyotes owe their color to a mutation that first arose in domestic dogs.[71]

A coywolf hybrid conceived in captivity between a male gray wolf and a female coyote

Eastern and red wolves are also products of varying degrees of wolf-coyote hybridization. The eastern wolf probably was a result of a wolf-coyote admixture, combined with extensive backcrossing with parent gray wolf populations. The red wolf may have originated during a time of declining wolf populations in the Southeastern Woodlands, forcing a wolf-coyote hybridization, as well as backcrossing with local parent coyote populations to the extent that about 75–80% of the modern red wolf's genome is of coyote derivation.[53][80]

Behavior

Social and reproductive behaviors

Mearns' coyote (C. l. mearnsi) pups playing

A pack of coyotes in Yellowstone National Park

Coyote pups are born in dens, hollow trees, or under ledges, and weigh 200 to 500 g (0.44 to 1.10 lb) at birth. They are altricial, and are completely dependent on milk for their first 10 days. The incisors erupt at about 12 days, the canines at 16, and the second premolars at 21. Their eyes open after 10 days, by which point the pups become increasingly more mobile, walking by 20 days, and running at the age of six weeks. The parents begin supplementing the pup's diet with regurgitated solid food after 12–15 days. By the age of four to six weeks, when their milk teeth are fully functional, the pups are given small food items such as mice, rabbits, or pieces of ungulate carcasses, with lactation steadily decreasing after two months.[22] Unlike wolf pups, coyote pups begin seriously fighting (as opposed to play fighting) prior to engaging in play behavior. A common play behavior includes the coyote "hip-slam".[74] By three weeks of age, coyote pups bite each other with less inhibition than wolf pups. By the age of four to five weeks, pups have established dominance hierarchies, and are by then more likely to play rather than fight.[87] The male plays an active role in feeding, grooming, and guarding the pups, but abandons them if the female goes missing before the pups are completely weaned. The den is abandoned by June to July, and the pups follow their parents in patrolling their territory and hunting. Pups may leave their families in August, though can remain for much longer. The pups attain adult dimensions at eight months, and gain adult weight a month later.[22]

Territorial and sheltering behaviors

Individual feeding territories vary in size from 0.4 to 62 km2 (0.15 to 24 sq mi), with the general concentration of coyotes in a given area depending on food abundance, adequate denning sites, and competition with conspecifics and other predators. The coyote generally does not defend its territory outside of the denning season,[22] and is much less aggressive towards intruders than the wolf is, typically chasing and sparring with them, but rarely killing them.[88] Conflicts between coyotes can arise during times of food shortage.[22] Coyotes mark their territories by raised-leg urination and ground-scratching.[89][84]Like wolves, coyotes use a den (usually the deserted holes of other species) when gestating and rearing young, though they may occasionally give birth under sagebrushes in the open. Coyote dens can be located in canyons, washouts, coulees, banks, rock bluffs, or level ground. Some dens have been found under abandoned homestead shacks, grain bins, drainage pipes, railroad tracks, hollow logs, thickets, and thistles. The den is continuously dug and cleaned out by the female until the pups are born. Should the den be disturbed or infested with fleas, the pups are moved into another den. A coyote den can have several entrances and passages branching out from the main chamber.[90] A single den can be used year after year.[23]

Hunting and feeding behaviors

While the popular consensus is that olfaction is very important for hunting,[91] two studies that experimentally investigated the role of olfactory, auditory, and visual cues found that visual cues are the most important ones for hunting in red foxes[92] and coyotes.[93][94]

A coyote pouncing on prey.

Coyotes may occasionally form mutualistic hunting relationships with American badgers, assisting each other in digging up rodent prey.[99] The relationship between the two species may occasionally border on apparent "friendship", as some coyotes have been observed laying their heads on their badger companions or licking their faces without protest. The amicable interactions between coyotes and badgers were known to pre-Columbian civilizations, as shown on a Mexican jar dated to 1250–1300 CE depicting the relationship between the two.[100]

Food scraps, pet food, and animal feces may attract a coyote to a trash can.[101]

Communication

A coyote howling

Body language

Being both a gregarious and solitary animal, the variability of the coyote's visual and vocal repertoire is intermediate between that of the solitary foxes and the highly social wolf.[81] The aggressive behavior of the coyote bears more similarities to that of foxes than it does that of wolves and dogs. An aggressive coyote arches its back and lowers its tail.[102] Unlike dogs, which solicit playful behavior by performing a "play-bow" followed by a "play-leap", play in coyotes consists of a bow, followed by side-to-side head flexions and a series of "spins" and "dives". Although coyotes will sometimes bite their playmates' scruff as dogs do, they typically approach low, and make upward-directed bites.[103] Pups fight each other regardless of sex, while among adults, aggression is typically reserved for members of the same sex. Combatants approach each other waving their tails and snarling with their jaws open, though fights are typically silent. Males tend to fight in a vertical stance, while females fight on all four paws. Fights among females tend to be more serious than ones among males, as females seize their opponents' forelegs, throat, and shoulders.[102]Vocalizations

The coyote has been described as "the most vocal of all [wild] North American mammals".[104][105] Its loudness and range of vocalizations was the cause for its binomial name Canis latrans, meaning "barking dog". At least 11 different vocalizations are known in adult coyotes. These sounds are divided into three categories: agonistic and alarm, greeting, and contact. Vocalizations of the first category include woofs, growls, huffs, barks, bark howls, yelps, and high-frequency whines. Woofs are used as low-intensity threats or alarms, and are usually heard near den sites, prompting the pups to immediately retreat into their burrows. Growls are used as threats at short distances, but have also been heard among pups playing and copulating males. Huffs are high-intensity threat vocalizations produced by rapid expiration of air. Barks can be classed as both long-distance threat vocalizations and as alarm calls. Bark howls may serve similar functions. Yelps are emitted as a sign of submission, while high-frequency whines are produced by dominant animals acknowledging the submission of subordinates. Greeting vocalizations include low-frequency whines, 'wow-oo-wows', and group yip howls. Low-frequency whines are emitted by submissive animals, and are usually accompanied by tail wagging and muzzle nibbling. The sound known as 'wow-oo-wow' has been described as a "greeting song". The group yip howl is emitted when two or more pack members reunite, and may be the final act of a complex greeting ceremony. Contact calls include lone howls and group howls, as well as the previously mentioned group yip howls. The lone howl is the most iconic sound of the coyote, and may serve the purpose of announcing the presence of a lone individual separated from its pack. Group howls are used as both substitute group yip howls and as responses to either lone howls, group howls, or group yip howls.[24]Ecology

Habitat

An urban coyote in Bernal Heights, San Francisco

Coyotes walk around 5–16 kilometres (3–10 mi) per day, often along trails such as logging roads and paths; they may use iced-over rivers as travel routes in winter. They are often crepuscular, being more active around evening and the beginning of the night than during the day. Like many canids, coyotes are competent swimmers, reported to be able to travel at least 0.8 kilometres (0.5 mi) across water.[106]

Diet

Although coyotes prefer fresh meat, they will scavenge when the opportunity presents itself. Excluding the insects, fruit, and grass eaten, the coyote requires an estimated 600 g (1.3 lb) of food daily, or 250 kg (550 lb) annually.[22] The coyote readily cannibalizes the carcasses of conspecifics, with coyote fat having been successfully used by coyote hunters as a lure or poisoned bait.[7] The coyote's winter diet consists mainly of large ungulate carcasses, with very little plant matter. Rodent prey increases in importance during the spring, summer, and fall.[5]

The coyote feeds on a variety of different produce, including blackberries, blueberries, peaches, pears, apples, prickly pears, chapotes, persimmons, peanuts, watermelons, cantaloupes, and carrots. During the winter and early spring, the coyote eats large quantities of grass, such as green wheat blades. It sometimes eats unusual items such as cotton cake, soybean meal, domestic animal droppings, beans, and cultivated grain such as maize, wheat, and sorghum.[22]

In coastal California, coyotes now consume a higher percentage of marine-based food than their ancestors, which is thought to be due to the extirpation of the grizzly bear from this region.[127] In Death Valley, coyotes may consume great quantities of hawkmoth caterpillars or beetles in the spring flowering months.[128]

Enemies and competitors

Comparative illustration of coyote and gray wolf

Mountain coyotes (C. l. lestes) cornering a juvenile cougar

Coyotes may compete with cougars in some areas. In the eastern Sierra Nevadas, coyotes compete with cougars over mule deer. Cougars normally outcompete and dominate coyotes, and may kill them occasionally, thus reducing coyote predation pressure on smaller carnivores such as foxes and bobcats.[131] Coyotes that are killed are sometimes not eaten, perhaps indicating that these compromise competitive interspecies interactions, however there are multiple confirmed cases of cougars also eating coyotes.[132][133] In northeastern Mexico, cougar predation on coyotes continues apace but coyotes were absent from the prey spectrum of sympatric jaguars, apparently due to differing habitat usages.[134]

Other than by gray wolves and cougars, predation on adult coyotes is relatively rare but multiple other predators can be occasional threats. In some cases, adult coyotes have been preyed upon by both American black and grizzly bears,[135] American alligators,[136] large Canada lynx[137] and golden eagles.[138] At kill sites and carrion, coyotes, especially if working alone, tend to be dominated by wolves, cougars, bears, wolverines and, usually but not always, eagles (i.e., bald and golden). When such larger, more powerful and/or more aggressive predators such as these come to a shared feeding site, a coyote may either try to fight, wait until the other predator is done or occasionally share a kill, but if a major danger such as wolves or an adult cougar is present, the coyote will tend to flee.[139][140][141][142][143][144][145][146]

Coyotes rarely kill healthy adult red foxes, and have been observed to feed or den alongside them, though they often kill foxes caught in traps. Coyotes may kill fox kits, but this is not a major source of mortality.[147] In southern California, coyotes frequently kill gray foxes, and these smaller canids tend to avoid areas with high coyote densities.[148]

In some areas, coyotes share their ranges with bobcats. These two similarly-sized species rarely physically confront one another, though bobcat populations tend to diminish in areas with high coyote densities.[149] However, several studies have demonstrated interference competition between coyotes and bobcats, and in all cases coyotes dominated the interaction.[150][151] Multiple researchers[152][153][154][151][155] reported instances of coyotes killing bobcats, whereas bobcats killing coyotes is more rare.[150] Coyotes attack bobcats using a bite-and-shake method similar to what is used on medium-sized prey. Coyotes (both single individuals and groups) have been known to occasionally kill bobcats – in most cases, the bobcats were relatively small specimens, such as adult females and juveniles.[151] However, coyote attacks (by an unknown number of coyotes) on adult male bobcats have occurred. In California, coyote and bobcat populations are not negatively correlated across different habitat types, but predation by coyotes is an important source of mortality in bobcats.[148] Biologist Stanley Paul Young noted that in his entire trapping career, he had never successfully saved a captured bobcat from being killed by coyotes, and wrote of two incidents wherein coyotes chased bobcats up trees.[100] Coyotes have been documented to directly kill Canada lynx on occasion,[156][157][158] and compete with them for prey, especially snowshoe hares.[156] In some areas, including central Alberta, lynx are more abundant where coyotes are few, thus interactions with coyotes appears to influence lynx populations more than the availability of snowshoe hares.[159]

Range

Range

of coyote subspecies as of 1978: (1) Mexican coyote, (2) San Pedro

Martir coyote, (3) El Salvador coyote, (4) southeastern coyote, (5)

Belize coyote, (6) Honduras coyote, (7) Durango coyote, (8) northern

coyote, (9) Tiburón Island coyote, (10) plains coyote, (11) mountain coyote, (12) Mearns' coyote,

(13) Lower Rio Grande coyote, (14) California valley coyote, (15)

peninsula coyote, (16) Texas plains coyote, (17) northeastern coyote,

(18) northwest coast coyote, (19) Colima coyote, (20) eastern coyote[61]

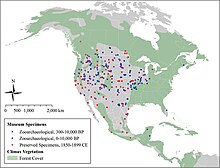

Coyote expansion over the past 10,000 years[160]

Coyote expansion over the decades since 1900[160]

Although it was once widely believed that coyotes are recent immigrants to southern Mexico and Central America, aided in their expansion by deforestation, Pleistocene and Early Holocene records, as well as records from the pre-Columbian period and early European colonization show that the animal was present in the area long before modern times. Nevertheless, range expansion did occur south of Costa Rica during the late 1970s and northern Panama in the early 1980s, following the expansion of cattle-grazing lands into tropical rain forests. The coyote is predicted to appear in northern Belize in the near future, as the habitat there is favorable to the species.[162] Concerns have been raised of a possible expansion into South America through the Panamanian Isthmus, should the Darién Gap ever be closed by the Pan-American Highway.[163] This fear was partially confirmed in January 2013, when the species was recorded in eastern Panama's Chepo District, beyond the Panama Canal.[64]

A 2017 genetic study proposes that coyotes were originally not found in the area of the eastern United States. From the 1890s, dense forests were transformed into agricultural land and wolf control implemented on a large scale, leaving a niche for coyotes to disperse into. There were two major dispersals from two populations of genetically distinct coyotes. The first major dispersal to the northeast came in the early 20th century from those coyotes living in the northern Great Plains. These came to New England via the northern Great Lakes region and southern Canada, and to Pennsylvania via the southern Great Lakes region, meeting together in the 1940s in New York and Pennsylvania. These coyotes have hybridized with the remnant gray wolf and eastern wolf populations, which has added to coyote genetic diversity and may have assisted adaptation to the new niche. The second major dispersal to the southeast came in the mid-20th century from Texas and reached the Carolinas in the 1980s. These coyotes have hybridized with the remnant red wolf populations before the 1970s when the red wolf was extirpated in the wild, which has also added to coyote genetic diversity and may have assisted adaptation to this new niche as well. Both of these two major coyote dispersals have experienced rapid population growth and are forecast to meet along the mid-Atlantic coast. The study concludes that for coyotes the long range dispersal, gene flow from local populations, and rapid population growth may be inter-related.[164]

Diseases and parasites

California valley coyote (C. l. ochropus) suffering from sarcoptic mange

Coyotes can be infected by both demodectic and sarcoptic mange, the latter being the most common. Mite infestations are rare and incidental in coyotes, while tick infestations are more common, with seasonal peaks depending on locality (May–August in the Northwest, March–November in Arkansas). Coyotes are only rarely infested with lice, while fleas infest coyotes from puphood, though they may be more a source of irritation than serious illness. Pulex simulans is the most common species to infest coyotes, while Ctenocephalides canis tends to occur only in places where coyotes and dogs (its primary host) inhabit the same area. Although coyotes are rarely host to flukes, they can nevertheless have serious effects on coyotes, particularly Nanophyetus salmincola, which can infect them with salmon poisoning disease, a disease with a 90% mortality rate. Trematode Metorchis conjunctus can also infect coyotes.[167] Tapeworms have been recorded to infest 60–95% of all coyotes examined. The most common species to infest coyotes are Taenia pisiformis and Taenia crassiceps, which uses cottontail rabbits as intermediate hosts. The largest species known in coyotes is T. hydatigena, which enters coyotes through infected ungulates, and can grow to lengths of 80 to 400 cm (31 to 157 in). Although once largely limited to wolves, Echinococcus granulosus has expanded to coyotes since the latter began colonizing former wolf ranges. The most frequent ascaroid roundworm in coyotes is Toxascaris leonina, which dwells in the coyote's small intestine and has no ill effects, except for causing the host to eat more frequently. Hookworms of the genus Ancylostoma infest coyotes throughout their range, being particularly prevalent in humid areas. In areas of high moisture, such as coastal Texas, coyotes can carry up to 250 hookworms each. The blood-drinking A. caninum is particularly dangerous, as it damages the coyote through blood loss and lung congestion. A 10-day-old pup can die from being host to as few as 25 A. caninum worms.[166]

Relationships with humans

In folklore and mythology

Coyote features as a trickster figure and skin-walker in the folktales of some Native Americans, notably several nations in the Southwestern and Plains regions, where he alternately assumes the form of an actual coyote or that of a man. As with other trickster figures, Coyote acts as a picaresque hero who rebels against social convention through deception and humor.[168] Folklorists such as Harris believe coyotes came to be seen as tricksters due to the animal's intelligence and adaptability.[169] After the European colonization of the Americas, Anglo-American depictions of Coyote are of a cowardly and untrustworthy animal.[170] Unlike the gray wolf, which has undergone a radical improvement of its public image, Anglo-American cultural attitudes towards the coyote remain largely negative.[171]

In the Maidu creation story, Coyote introduces work, suffering, and death to the world. Zuni lore has Coyote bringing winter into the world by stealing light from the kachinas. The Chinook, Maidu, Pawnee, Tohono O'odham, and Ute portray the coyote as the companion of The Creator. A Tohono O'odham flood story has Coyote helping Montezuma survive a global deluge that destroys humanity. After The Creator creates humanity, Coyote and Montezuma teach people how to live. The Crow creation story portrays Old Man Coyote as The Creator. In The Dineh creation story, Coyote was present in the First World with First Man and First Woman, though a different version has it being created in the Fourth World. The Navajo Coyote brings death into the world, explaining that without death, too many people would exist, thus no room to plant corn.[172]

Mural from Atetelco, Teotihuacán depicting coyote warriors

Attacks on humans

A

sign discouraging people from feeding coyotes, which can lead to them

habituating themselves to human presence, thus increasing the likelihood

of attacks

In the absence of the harassment of coyotes practiced by rural people, urban coyotes are losing their fear of humans, which is further worsened by people intentionally or unintentionally feeding coyotes. In such situations, some coyotes have begun to act aggressively toward humans, chasing joggers and bicyclists, confronting people walking their dogs, and stalking small children.[177] Non-rabid coyotes in these areas sometimes target small children, mostly under the age of 10, though some adults have been bitten.[180]

Although media reports of such attacks generally identify the animals in question as simply "coyotes", research into the genetics of the eastern coyote indicates those involved in attacks in northeast North America, including Pennsylvania, New York, New England, and eastern Canada, may have actually been coywolves, hybrids of Canis latrans and C. lupus, not fully coyotes.[181]

Livestock and pet predation

Coyote confronting a dog

Livestock guardian dogs are commonly used to aggressively repel predators and have worked well in both fenced pasture and range operations.[189] A 1986 survey of sheep producers in the USA found that 82% reported the use of dogs represented an economic asset.[190]

Re-wilding cattle, which involves increasing the natural protective tendencies of cattle, is a method for controlling coyotes discussed by Temple Grandin of Colorado State University.[191] This method is gaining popularity among producers who allow their herds to calve on the range and whose cattle graze open pastures throughout the year.[192]

Coyotes typically bite the throat just behind the jaw and below the ear when attacking adult sheep or goats, with death commonly resulting from suffocation. Blood loss is usually a secondary cause of death. Calves and heavily fleeced sheep are killed by attacking the flanks or hindquarters, causing shock and blood loss. When attacking smaller prey, such as young lambs, the kill is made by biting the skull and spinal regions, causing massive tissue and bone damage. Small or young prey may be completely carried off, leaving only blood as evidence of a kill. Coyotes usually leave the hide and most of the skeleton of larger animals relatively intact, unless food is scarce, in which case they may leave only the largest bones. Scattered bits of wool, skin, and other parts are characteristic where coyotes feed extensively on larger carcasses.[182]

Coyote with a typical throat hold on a domestic sheep

Coyotes are often attracted to dog food and animals that are small enough to appear as prey. Items such as garbage, pet food, and sometimes feeding stations for birds and squirrels attract coyotes into backyards. About three to five pets attacked by coyotes are brought into the Animal Urgent Care hospital of South Orange County (California) each week, the majority of which are dogs, since cats typically do not survive the attacks.[195] Scat analysis collected near Claremont, California, revealed that coyotes relied heavily on pets as a food source in winter and spring.[177] At one location in Southern California, coyotes began relying on a colony of feral cats as a food source. Over time, the coyotes killed most of the cats, and then continued to eat the cat food placed daily at the colony site by people who were maintaining the cat colony.[177] Coyotes usually attack smaller-sized dogs, but they have been known to attack even large, powerful breeds such as the Rottweiler in exceptional cases.[196] Dogs larger than coyotes, such as greyhounds, are generally able to drive them off, and have been known to kill coyotes.[197] Smaller breeds are more likely to suffer injury or death.[180]

Hunting

Coyote tracks compared to that of the Domestic dog's tracks.

Prior to the mid-19th century, coyote fur was considered worthless. This changed with the diminution of beavers, and by 1860, the hunting of coyotes for their fur became a great source of income (75 cents to $1.50 per skin) for wolfers in the Great Plains. Coyote pelts were of significant economic importance during the early 1950s, ranging in price from $5 to $25 per pelt, depending on locality.[201] The coyote's fur is not durable enough to make rugs,[202] but can be used for coats and jackets, scarves, or muffs. The majority of pelts are used for making trimmings, such as coat collars and sleeves for women's clothing. Coyote fur is sometimes dyed black as imitation silver fox.[201]

Coyotes were occasionally eaten by trappers and mountain men during the western expansion. Coyotes sometimes featured in the feasts of the Plains Indians, and coyote pups were eaten by the indigenous people of San Gabriel, California. The taste of coyote meat has been likened to that of the wolf, and is more tender than pork when boiled. Coyote fat, when taken in the fall, has been used on occasion to grease leather or eaten as a spread.[203]

Tameability

Coyotes were probably semidomesticated by various pre-Columbian cultures. Some 19th-century writers wrote of coyotes being kept in native villages in the Great Plains. The coyote is easily tamed as a pup, but can become destructive as an adult.[204] Both full-blooded and hybrid coyotes can be playful and confiding with their owners, but are suspicious and shy of strangers,[72] though coyotes being tractable enough to be used for practical purposes like retrieving[205] and pointing have been recorded.[206] A tame coyote named "Butch", caught in the summer of 1945, had a short-lived career in cinema, appearing in Smoky and Ramrod before being shot while raiding a henhouse.[204]Notes

Binomial name

Canis latrans

Modern range of Canis latrans

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.