The okapi (/oʊˈkɑːpiː/; Okapia johnstoni), also known as the forest giraffe, Congolese giraffe, or zebra giraffe, is an artiodactyl mammal native to the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Central Africa. Although the okapi has striped markings reminiscent of zebras, it is most closely related to the giraffe. The okapi and the giraffe are the only living members of the family Giraffidae.

The okapi stands about 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall at the shoulder and

has a typical body length around 2.5 m (8.2 ft). Its weight ranges from

200 to 350 kg (440 to 770 lb). It has a long neck, and large, flexible

ears. Its coat is a chocolate to reddish brown, much in contrast with

the white horizontal stripes and rings on the legs, and white ankles.

Male okapis have short, distinct horn-like protuberances on their heads

called ossicones (which share similar features to the giraffe ossicones in terms of formation, structure and function)[2], less than 15 cm (5.9 in) in length. Females possess hair whorls, and ossicones are absent.

Okapis are primarily diurnal, but may be active for a few hours in darkness. They are essentially solitary, coming together only to breed. Okapis are herbivores, feeding on tree leaves and buds, grasses, ferns, fruits, and fungi. Rut in males and estrus in females does not depend on the season. In captivity, estrous cycles recur every 15 days. The gestational period

is around 440 to 450 days long, following which usually a single calf

is born. The juveniles are kept in hiding, and nursing takes place

infrequently. Juveniles start taking solid food from three months, and

weaning takes place at six months.

Okapis inhabit canopy

forests at altitudes of 500–1,500 m (1,600–4,900 ft). They are endemic

to the tropical forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where

they occur across the central, northern, and eastern regions. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources classifies the okapi as endangered. Major threats include habitat loss due to logging and human settlement. Extensive hunting for bushmeat and skin and illegal mining have also led to a decline in populations. The Okapi Conservation Project was established in 1987 to protect okapi populations.

Etymology and taxonomy

Although the okapi was unknown to the Western world until the 20th

century, it may have been depicted since the early fifth century BCE on

the façade of the Apadana at Persepolis, a gift from the Ethiopian procession to the Achaemenid kingdom.[3]

For years, Europeans in Africa had heard of an animal that they came to call the African unicorn.[4][5] The animal was brought to prominent European attention by speculation on its existence found in press reports covering Henry Morton Stanley's journeys in 1887. In his travelogue of exploring the Congo, Stanley mentioned a kind of donkey that the natives called the atti,

which scholars later identified as the okapi. Explorers may have seen

the fleeting view of the striped backside as the animal fled through the

bushes, leading to speculation that the okapi was some sort of

rainforest zebra.[citation needed]

When the British special commissioner in Uganda, Sir Harry Johnston, discovered some Pygmy

inhabitants of the Congo being abducted by a showman for exhibition, he

rescued them and promised to return them to their homes. The Pygmies

fed Johnston's curiosity about the animal mentioned in Stanley's book.

Johnston was puzzled by the okapi tracks the natives showed him; while

he had expected to be on the trail of some sort of forest-dwelling

horse, the tracks were of a cloven-hoofed beast.[6]

Okapia johnstoni was first described as Equus johnstoni by English zoologist Philip Lutley Sclater in 1901.[8] The generic name Okapia derives either from the Mbuba name okapi[9] or the related Lese Karo name o'api, while the specific name (johnstoni) is in recognition of Johnston, who first acquired an okapi specimen for science from the Ituri Forest.[7][10] Remains of a carcass were later sent to London by Johnston and became a media event in 1901.[11]

In 1901, Sclater presented a painting of the okapi before the Zoological Society of London that depicted its physical features with some clarity. Much confusion arose regarding the taxonomical status of this newly discovered animal. Sir Harry Johnston himself called it a Helladotherium, or a relative of other extinct giraffids.[12] Based on the description of the okapi by Pygmies, who referred to it as a "horse", Sclater named the species Equus johnstoni.[13] Subsequently, zoologist Ray Lankester declared that the okapi represented an unknown genus of the Giraffidae, which he placed in its own genus, Okapia, and assigned the name Okapia johnstoni to the species.[14]

In 1902, Swiss zoologist Charles Immanuel Forsyth Major suggested the inclusion of O. johnstoni in the extinct giraffid subfamily Palaeotraginae. However, the species was placed in its own subfamily Okapiinae, by Swedish palaeontologist Birger Bohlin in 1926,[15] mainly due to the lack of a cingulum, a major feature of the palaeotragids.[16] In 1986, Okapia was finally established as a sister genus of Giraffa on the basis of cladistic analysis. The two genera together with Palaeotragus constitute the tribe Giraffini.[17]

Evolution

The earliest members of the Giraffidae first appeared in the early Miocene in Africa, having diverged from the superficially deer-like climacoceratids. Giraffids spread into Europe and Asia by the middle Miocene in a first radiation. Another radiation began in the Pliocene, but was terminated by a decline in diversity in the Pleistocene.[18] Several important primitive giraffids existed more or less contemporaneously in the Miocene (23–10 million years ago), including Canthumeryx, Giraffokeryx, Palaeotragus, and Samotherium. According to palaeontologist and author Kathleen Hunt, Samotherium split into Okapia (18 million years ago) and Giraffa (12 million years ago).[19] However, J. D. Skinner argued that Canthumeryx gave rise to the okapi and giraffe through the latter three genera and that the okapi is the extant form of Palaeotragus.[20] The okapi is sometimes referred to as a living fossil, as it has existed as a species over a long geological time period, and morphologically resembles more primitive forms (e.g. Samotherium).[14][21]

In 2016, a genetic study found that the common ancestor of giraffe and okapi lived about 11.5 million years ago.[22]

Characteristics

The okapi shows several adaptations to its tropical habitat. The large number of rod cells in the retina facilitate night vision, and an efficient olfactory system is present. The large auditory bullae allow a strong sense of hearing. The dental formula of the okapi is 0.0.3.33.1.3.3.[25] Teeth are low-crowned and finely cusped, and efficiently cut tender foliage. The large caecum and colon help in microbial digestion, and a quick rate of food passage allows for lower cell wall digestion than in other ruminants.[28]

Ecology and behaviour

Okapis are primarily diurnal, but may be active for a few hours in darkness.[30]

They are essentially solitary, coming together only to breed. They have

overlapping home ranges and typically occur at densities around 0.6

animals per square kilometre.[24] Male home ranges average 13 km2 (5.0 sq mi), while female home ranges average 3–5 km2 (1.2–1.9 sq mi). Males migrate continuously, while females are sedentary.[31]

Males often mark territories and bushes with their urine, while females

use common defecation sites. Grooming is a common practice, focused at

the earlobes and the neck. Okapis often rub their necks against trees,

leaving a brown exudate.[25]

The male is protective of his territory, but allows females to

pass through the domain to forage. Males visit female home ranges at

breeding time.[28] Although generally tranquil, the okapi can kick and butt with its head to show aggression. As the vocal cords

are poorly developed, vocal communication is mainly restricted to three

sounds — "chuff" (contact calls used by both sexes), "moan" (by females

during courtship) and "bleat" (by infants under stress). Individuals

may engage in Flehmen response,

a visual expression in which the animal curls back its upper lips,

displays the teeth, and inhales through the mouth for a few seconds. The

leopard is the main natural predator of the okapi.[25]

Diet

Reproduction

Reproduction

The gestational period is around 440 to 450 days long, following which usually a single calf is born, weighing 14–30 kg (31–66 lb). The udder of the pregnant female starts swelling 2 months before parturition, and vulval discharges may occur. Parturition takes 3–4 hours, and the female stands throughout this period, though she may rest during brief intervals. The mother consumes the afterbirth and extensively grooms the infant. Her milk is very rich in proteins and low in fat.[28]

As in other ruminants, the infant can stand within 30 minutes of birth. Although generally similar to adults, newborn calves have false eyelashes, a long dorsal mane, and long white hairs in the stripes. These features gradually disappear and give way to the general appearance within a year. The juveniles are kept in hiding, and nursing takes place infrequently. Calves are known not to defecate for the first month or two of life, which is hypothesized to help avoid predator detection in their most vulnerable phase of life.[34] The growth rate of calves is appreciably high in the first few months of birth, after which it gradually declines. Juveniles start taking solid food from 3 months, and weaning takes place at 6 months. Horn development in males takes 1 year after birth. The okapi's typical lifespan is 20–30 years.[25]

Distribution and habitat

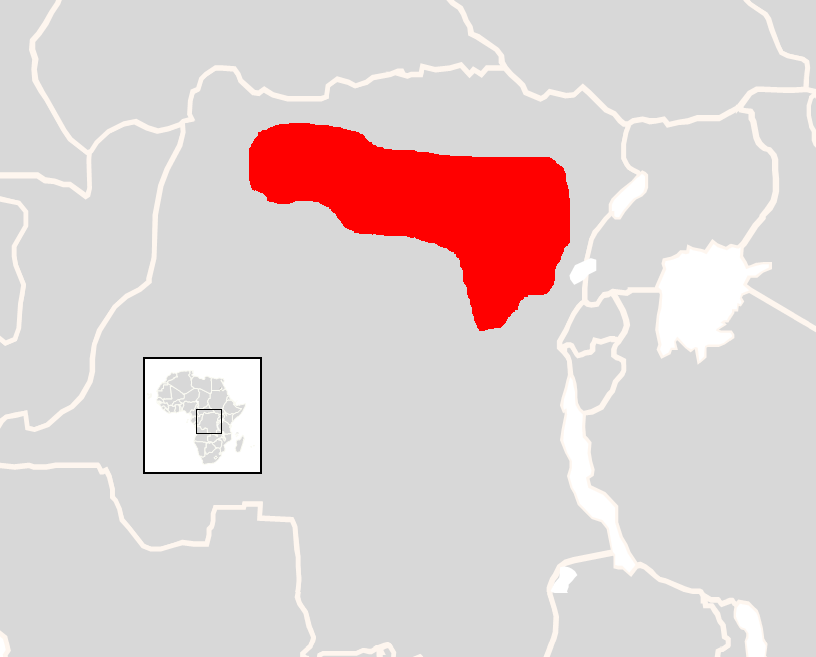

The okapi is endemic to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where it occurs north and east of the Congo River. It ranges from the Maiko National Park northward to the Ituri rainforest, then through the river basins of the Rubi, Lake Tele, and Ebola to the west and the Ubangi River further north. Smaller populations exist west and south of the Congo River. It is also common in the Wamba and Epulu areas. It is extinct in Uganda.[1]

The okapi inhabits canopy forests at altitudes of 500–1,500 m (1,600–4,900 ft). It occasionally uses seasonally inundated areas, but does not occur in gallery forests, swamp forests, and habitats disturbed by human settlements. In the wet season, it visits rocky inselbergs that offer forage uncommon elsewhere. Results of research conducted in the late 1980s in a mixed Cynometra forest indicated that the okapi population density averaged 0.53 animals per square kilometre.[31]

In 2008, it was recorded in Virunga National Park.[35]

Status

Threats and conservation

The Okapi Conservation Project, established in 1987, works towards the conservation of the okapi, as well as the growth of the indigenous Mbuti people.[1] In November 2011, the White Oak Conservation center and Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens hosted an international meeting of the Okapi Species Survival Plan and the Okapi European Endangered Species Programme at Jacksonville, which was attended by representatives from zoos from the US, Europe, and Japan. The aim was to discuss the management of captive okapis and arrange support for okapi conservation. Many zoos in North America and Europe currently have okapis in captivity.[39]

The Bronx Zoo was the first zoo in North America to exhibit okapi, in 1937.[42] They have had one of the most successful breeding programs, with 13 calves having been born since 1991.[43]

The San Diego Zoo

has exhibited okapis since 1956, and had their first birth of an okapi

in 1962. Since then, over 60 births have occurred between the zoo and

the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, with the most recent being Mosi, a male calf born in early August 2017 at the San Diego Zoo.[44]

The Brookfield Zoo in Chicago

has also greatly contributed to the captive population of okapis in

accredited zoos. The zoo has had 28 okapi births since 1959.[45]

Other North American Zoos that exhibit and breed okapis include the Denver Zoo and Cheyenne Mountain Zoo (Colorado); Houston Zoo, Dallas Zoo and San Antonio Zoo (Texas); Disney's Animal Kingdom, Miami Zoo and Tampa's Lowry Park Zoo (Florida); Los Angeles Zoo (California); Saint Louis Zoo (Missouri); Cincinnati Zoo and Columbus Zoo (Ohio); Memphis Zoo (Tennessee); Maryland Zoo (Maryland) and The Sedgwick County Zoo and Tanganyika Wildlife Park (Kansas); Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo (Nebraska); Philadelphia Zoo (Philadelphia).[46]

In Europe, zoos that exhibit and breed okapis include Madrid Zoo (Spain), Chester Zoo, London Zoo, Yorkshire Wildlife Park, Marwell Zoo, The Wild Place (United Kingdom); Dublin Zoo (Ireland); Berlin Zoo, Frankfurt Zoo, Wilhelma Zoo, Wuppertal Zoo, Cologne Zoo, Leipzig Zoo (Germany) and Antwerp Zoo (Belgium); Zoo Basel (Switzerland); Copenhagen Zoo (Denmark); Rotterdam Zoo, Safaripark Beekse Bergen (Netherlands) and Dvůr Králové Zoo (Czech Republic), Wrocław Zoo (Poland); Bioparc Zoo de Doué, ZooParc de Beauval (France); Lisbon Zoo (Portugal).[47][48]

In Asia, only two zoos in Japan exhibit okapis; Ueno Zoo in Tokyo and Zoorasia in Yokohama.[49]

Range of the okapi

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.