Standing up to a metre tall, adults weigh from 1 to 2 kg (2.2 to 4.4 lb). They have a white head and neck with a broad black stripe that extends from the eye to the black crest. The body and wings are grey above and the underparts are greyish-white, with some black on the flanks. The long, sharply pointed beak is pinkish-yellow and the legs are brown.

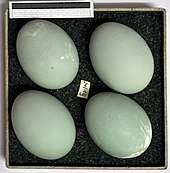

The birds breed colonially in spring in "heronries", usually building their nests high in trees. A clutch of usually three to five bluish-green eggs is laid. Both birds incubate the eggs for a period of about 25 days, and then both feed the chicks, which fledge when seven or eight weeks old. Many juveniles do not survive their first winter, but if they do, they can expect to live for about five years.

In Ancient Egypt, the deity Bennu was depicted as a heron in New Kingdom artwork. In Ancient Rome, the heron was a bird of divination. Roast heron was once a specially-prized dish; when George Neville became Archbishop of York in 1465, four hundred herons were served to the guests.

Description

Head, with neck retracted

The main call is a loud croaking "fraaank", but a variety of guttural and raucous noises are heard at the breeding colony. The male uses an advertisement call to encourage a female to join him at the nest, and both sexes use various greeting calls after a pair bond has been established. A loud, harsh "schaah" is used by the male in driving other birds from the vicinity of the nest and a soft "gogogo" expresses anxiety, as when a predator is nearby or a human walks past the colony. The chicks utter loud chattering or ticking noises.[4]

Taxonomy and evolution

(video) A grey heron foraging on mudflats

Herons are members of the family Ardeidae, and the majority of extant species are in the subfamily Ardeinae and known as true or typical herons. This subfamily includes the herons and egrets, the green herons, the pond herons, the night herons and a few other species. The grey heron belongs in this subfamily and is placed in the genus Ardea, which also includes the cattle egret and the great egret.[5] The grey heron was first described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus who gave it the name Ardea cinerea. The scientific name comes from Latin ardea "heron", and cinerea , "ash-grey" (from cineris ashes).[6]

Four subspecies are recognised:[7]

- A. c. cinerea – Linnaeus, 1758: nominate, found in Europe, Africa, western Asia

- A. c. jouyi – Clark, 1907: found in eastern Asia

- A. c. firasa – Hartert, 1917: found in Madagascar

- A. c. monicae – Jouanin & Roux, 1963: found on islands off Banc d'Arguin, Mauritania.

Distribution and habitat

In flight

Over much of its range, the grey heron is resident, but birds from the more northerly parts of Europe migrate southwards, some remaining in central and southern Europe, others travelling on to Africa south of the Sahara Desert.[4]

Within its range, the grey heron can be found anywhere with suitable watery habitat that can supply its food. The water body needs to be either shallow enough, or have a shelving margin in which it can wade. Although most common in the lowlands it also occurs in mountain tarns, lakes, reservoirs, large and small rivers, marshes, ponds, ditches, flooded areas, coastal lagoons, estuaries and the sea shore. It sometimes forages away from water in pasture, and it has been recorded in desert areas, hunting for beetles and lizards. Breeding colonies are usually near feeding areas but exceptionally may be up to 8 kilometres (5 mi) away, and birds sometimes forage as much as 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the nesting site.[4]

Behavior

The grey heron has a slow flight, with its long neck retracted (S-shaped). This is characteristic of herons and bitterns, and distinguishes them from storks, cranes, and spoonbills, which extend their necks.[4] It flies with slow wing-beats and sometimes glides for short distances. It sometimes soars, circling to considerable heights, but not as often as the stork. In spring, and occasionally in autumn, birds may soar high above the heronry and chase each other, undertake aerial manoeuvres or swoop down towards the ground. The birds often perch in trees, but spend much time on the ground, striding about or standing still for long periods with an upright stance, often on a single leg.[4]Diet and feeding

Swallowing an eel

Small fish are swallowed head first, and larger prey and eels are carried to the shore where they are subdued by being beaten on the ground or stabbed by the bill. They are then swallowed, or have hunks of flesh torn off. For avian prey such as small birds and ducklings, the prey is held by the neck and either suffocated or killed by having its neck snapped with the heron's beak, before being swallowed whole. The bird regurgitates pellets of indigestible material such as fur, bones and the chitinous remains of insects. The main periods of hunting are around dawn and dusk, but it is also active at other times of day. At night it roosts in trees or on cliffs, where it tends to be gregarious.[4]

Breeding

This species breeds in colonies known as heronries, usually in high trees close to lakes, the seashore or other wetlands. Other sites are sometimes chosen, and these include low trees and bushes, bramble patches, reed beds, heather clumps and cliff ledges. The same nest is used year after year until blown down; it starts as a small platform of sticks but expands into a bulky nest as more material is added in subsequent years. It may be lined with smaller twigs, strands of root or dead grasses, and in reed beds, it is built from dead reeds. The male usually collects the material while the female constructs the nest. Breeding activities take place between February and June. When a bird arrives at the nest, a greeting ceremony occurs in which each partner raises and lowers its wings and plumes.[11] In continental Europe, and elsewhere, nesting colonies sometimes include nests of the purple heron and other heron species.[4]

Building nest

Eggs, collection Museum Wiesbaden

The oldest recorded bird lived for twenty-three years but the average life expectancy in the wild is about five years. Only about a third of juveniles survive into their second year, many falling victim to predation.[11]

City life

Seeking food from a zoo penguin enclosure

Herons have been observed visiting water enclosures in zoos, such as spaces for penguins, otters, pelicans, and seals, and taking food meant for the animals on display.[16][17][18][19]

Predators and parasites

Being large birds with powerful beaks, grey herons have few predators as adults, but the eggs and young are more vulnerable. The adult birds do not usually leave the nest unattended, but may be lured away by marauding crows or kites.[20] A dead grey heron found in the Pyrenees is thought to have been killed by an otter. The bird may have been weakened by harsh winter weather causing scarcity of its prey.[21]A study performed by Sitko and Heneberg in the Czech Republic between 1962 and 2013 suggested that central European grey herons host 29 species of parasitic worms. The dominant species consisted of Apharyngostrigea cornu (67% prevalence), Posthodiplostomum cuticola (41% prevalence), Echinochasmus beleocephalus (39% prevalence), Uroproctepisthmium bursicola (36% prevalence), Neogryporhynchus cheilancristrotus (31% prevalence), Desmidocercella numidica (29% prevalence) and Bilharziella polonica (5% prevalence). Juvenile grey herons were shown to host fewer species, but the intensity of infection was higher in the juveniles than in the adult herons. Of the digenean flatworms found in central European grey herons, 52% of the species likely infected their definitive hosts outside central Europe itself, in the pre-migratory, migratory, or wintering quarters, despite the fact that a substantial proportion of grey herons do not migrate to the south.[22]

In human culture

"The Heron. Common Heron, Heronsewgh, or Heronshaw. (Ardea cinerea, Lath.—Héron cendré, Temm.)" wood engraving by Thomas Bewick in his History of British Birds, volume 2, 1804

In Ancient Rome, the heron was a bird of divination that gave an augury (sign of a coming event) by its call, like the raven, stork, and owl.[24]

Roast heron was once a specially-prized dish in Britain for special occasions such as state banquets. For the appointment of George Neville as Archbishop of York in 1465, four hundred herons were served to the guests. Young birds were still being shot and eaten in Romney Marsh in 1896. Two grey herons feature in a stained glass window of the church in Selborne, Hampshire.[25]

The English surnames Earnshaw, Hernshaw, Herne, and Heron all derive from the heron, the suffix -shaw meaning a wood, referring to a place where herons nested.[26]

Range of A. cinerea Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.