Two subspecies occur: C. h. hectori, the more numerous subspecies, is found around the South Island, and the critically endangered Maui's dolphin (C. h. maui) is found off the northwest coast of the North Island.[2] Hector's dolphin is the world's smallest and rarest dolphin.[3] Maui's dolphin is one of the eight most endangered groups of cetaceans. A 2010/2011 survey of Maui's dolphin by the New Zealand Department of Conservation estimated only 55 adults remain.[4]

Hector's dolphin was named after Sir James Hector (1834–1907), who was the curator of the Colonial Museum in Wellington (now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa). He examined the first specimen found of the dolphin. The species was scientifically described by Belgian zoologist Pierre-Joseph van Beneden in 1881.

Māori names for Hector's and Maui's dolphin include tutumairekurai, tupoupou and popoto.

Description

Hector's dolphin has a unique rounded dorsal fin.

The overall coloration appearance is pale grey, but closer inspection reveals a complex and elegant combination of colours. The back and sides are predominantly light grey, while the dorsal fin, flippers, and flukes are black. The eyes are surrounded by a black mask, which extends forward to the tip of the rostrum and back to the base of the flipper. A subtly shaded, crescent-shaped black band crosses the head just behind the blowhole. The throat and belly are creamy white, separated by dark-grey bands meeting between the flippers. A white stripe extends from the belly onto each flank below the dorsal fin.

At birth, Hector’s dolphin calves have a total length of 60–80 cm (24–31 in) and weigh 8–10 kg (18–22 lb).[7] Their coloration is the almost same as adults, although the grey has a darker hue. Newborn Hector’s dolphins have distinct fetal fold marks on their flanks that cause a change in coloration pattern of the skin. These changes are visible for approximately 6 months and consist of four to six vertical light grey stripes against darker grey skin.[7]

Population and distribution

Hector's dolphins are endemic to the coastal regions of New Zealand. The species has a fragmented distribution around the entire South Island. Very occasional sightings of these individuals occur in the deep waters of Fiordland. The members of the species that inhabit the North Island (C. hectori maui) make up a genetically distinct allopatric population from Hector's dolphins.[2] , As of 2011, five areas are designed as marine mammal sanctuaries focusing on Hector's and Maui's dolphins around the nation.[8]The largest populations live on the east and west coasts of the South Island, most notably on Banks Peninsula and Te Waewae Bay[9][10] while smaller local groups are scattered along entire South Island coasts such as at Cook Strait, Kaikoura, West Coast, Catlins (e.g. Porpoise Bay, Curio Bay), and Otago coasts (e.g.Karitane, Oamaru, Moeraki, Otago Harbour, Blueskin Bay).[11] Maui's dolphin lives on the west coast of the North Island between Maunganui Bluff and Whanganui.[12] Occasionally, Hector's dolphins can reach the North Island up to Bay of Plenty or Hawke's Bay.[13]

The latest estimate of South Island Hector's dolphins carried out by the Ministry for Primary Industries is around 15,000 individuals and almost twice the previous, published estimate.[14] Problems with the survey methods and data analysis, identified in peer review, are to be discussed when the Hector's dolphin Threat Management Plan is reviewed in 2018. Until that review, it is reasonable to conclude that the current population is on the order of 10,000 Hector's dolphins. The current population is below 30% of the population estimated in 1970 which was about 50,000.[15] The latest estimate of Maui's dolphin is 55 individuals (1 year and older). Additional population surveys have been carried out off the east coast in 2012 and 2013. The results of these surveys have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

The species' range includes shallow waters down to 100 m (330 ft) deep, with very few sightings in deeper waters.[16][17] Hector’s dolphins showcase a seasonal inshore-offshore movement; they favor shallow and murky waters during the spring and summer months, but move offshore to deeper waters during autumn and winter. Despite this pattern, they are rarely seen farther than 8-10 km from shore. They have also been shown to return to the same location during consecutive summers, displaying high site fidelity, i.e. returning to the same location. This hinders gene flow between populations and ultimately leads to gene isolation. Hector’s dolphins have not been found to participate in alongshore migrations, which may also contribute to their lack of genetic diversity. The inshore-offshore movement of the species may be attributed to the patterns of fish and squid moving to spawning grounds or an increase in fish diversity close to the shore during the spring and summer months.[18]

Population Dynamics

Hector’s dolphins preferentially form groups of less than 5 individuals, with a mean of 3.8 individuals, that are highly segregated by sex. The majority of these small groups are single sex. Groups of greater than 5 individuals are formed much less frequently. These larger groups, >5, are usually mixed sex and have been shown to form only to forage or participate in sexual behavior. Nursery groups can also be observed and are usually all female groups of less than 7 mother and young.[6]This species has been found to be show a high level of fluidity with weak inter-individual associations, meaning they do not form strong bonds with other individuals. Three types of small preferential groups have been found: nursery groups; immature and subadult groups; and adult male/female groups. All of these small groups show a high level of sex segregation. Hector’s dolphins display a sex-age population group composition, meaning they group by biological sex and age.[18]

Ecology and life history

Data from field studies, stranded individuals, and dolphins caught in fishing nets have provided information on their life history and reproductive parameters.[5] Photo-ID research at Banks Peninsula, and other locations around the South and North Island since 1984 has shown that individuals reach around 23 years of age.Overall life-history characteristics mean that Hector's dolphins, like many other small cetaceans, have a low potential for population growth. Maximum population growth rate has been estimated to be 1.8-4.9% per year, although the lower end of this range is probably more realistic.[19]

Reproduction

Males attain sexual maturity between 6 and 9 years old and females begin birthing young between 7 to 9 years old. Females will continue to birth calves every 2-3 years, resulting in a maximum of 4-7 calves in one female’s lifetime. Calves are birthed during the spring and summer.[20] Calf mortality within the first 6 months of life has been found to be approximately 36%. Calves were found to breastfeed until close to a year old.[18]Males of the species have extremely large testes in proportion to body size, with the highest relative weight in one study being 2.9% of body weight. Large testes in combination with males’ smaller overall body size suggests a promiscuous mating system. This type of reproductive system would involve a male attempting to fertilize as many females as possible and little male-male aggression. The amount of sexual behavior per individual in the species is observed most when small single sex groups form large mixed sex groups. Sexual behavior in the species is usually non aggressive.[20]

Foraging and predation

Hector's dolphins at Porpoise Bay, in the Catlins

Hector's dolphins are generalist feeders, with prey selection based on size rather than species. Typically, they feed on smaller prey which tend to measure under 10 cm. in length.[22] Stomach contents of dissected dolphins have included surface-schooling fish, midwater fish, and squid, and a wide variety of benthic species.[23] The largest prey item recovered from a Hector's dolphin stomach was an undigested red cod weighing 500 g with a standard length of 35 cm. Many Hector's dolphins can be observed following fishing trawlers as a result of the amount of disturbed or escaped flatfish and red cod on which the species typically feed. However, this activity can result in the unwanted bycatching of the species.[24]

Similar to the Hourglass Dolphin, Hector's dolphins use high-frequency echolocation clicks. However, the Hector's Dolphin produces lower source-level clicks than Hourglass Dolphins due to their crowded environment. This means they can only spot prey at half the distance compared to an hourglass dolphin.[25] The species has a very simple repertoire with few types of clicks, as well as little audible signals in addition to these. More complex clicks could be observed in large groups.[26]

Natural predators of Hector’s dolphins include sharks and killer whales (orca). Remains of Hector's have been found in sevengill and blue shark stomachs.[27]

Although the biggest threat to this endangered species is inshore fishing, they also suffer from an infectious agent, Toxoplasma gondii. A study of 28 captured Hector's dolphins showed seven of them died due to toxoplasmosis. These dolphins were examined, and haemorrhagic lesions in the lungs, liver, lymph nodes, and adrenals were found.[28]

Loss of genetic diversity and population decline

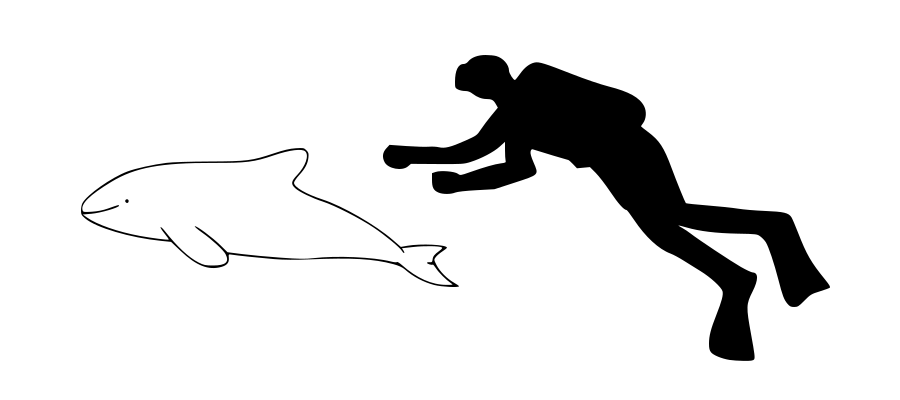

Size compared to an average human

The high levels of sex segregation and fragmentation of different populations in Hector’s dolphin have been discussed as contributing to the overall population decline, as it becomes more difficult for males to find a female and copulate. The Allee effect begins to occur when a low density population has low reproductive rates leading to increased population decline.[29]

Samples from 1870 to today have provided a historical timeline for the species' population decline. Lack of neighboring populations due to fishery related mortality has decreased gene flow and contributed to overall loss in mitochondrial DNA diversity. As a result, the populations have become fragmented and isolated, leading to inbreeding. Geographical range has been lessened to the point where gene flow and immigration may no longer be possible between Maui's dolphin and Hector's dolphin. [30] [31]

Conservation

Dolphin deaths in bottom-set gillnets and trawl fisheries[32] have been responsible for substantial population declines in the last four decades. Gill-nets are made from lightweight monofilament that is difficult for dolphins to detect, especially when they are distracted (e.g. chasing fish) or moving around without using echolocation. Hector's and Maui's dolphins swim into the nets, get caught, and drown - or more accurately, suffocate (breathing is active in dolphins). Hector's dolphins are actively attracted to trawling vessels and can frequently be seen following trawlers and diving down to the net. They have been observed to follow 100-200m behind trawlers in large groups to forage, even picking fish out of the net itself.[24] Occasional mistakes can lead to injury or death.The nationwide estimate for bycatch in commercial gillnets is 110-150 dolphins per year[33] which is far in excess of the sustainable level of human impact.[34] Deaths in fishing nets are the most serious threat (responsible for more than 95% of the human-caused deaths in Maui's dolphins), with currently lower level threats including tourism, disease, and marine mining.[35][36] Research of decreases in mitochondrial DNA diversity among hector's dolphin populations has suggested that the amount of gill-net entanglement deaths likely far surpasses that reported by fisheries.[30]

The New Zealand government proposed a set of plans to avoid further extinction of Hector's dolphin, including protecting/closing areas where dolphins are normally found and changing fishing methods to avoid catching dolphins. The plan involves three steps; The first is to change voluntary codes involving practice and monitoring for fisherman. The second is to close inshore areas from fishing. The third plan is formed around the potential biological removal (PBR) concept which tells how much change would need to be done to protect the dolphins and how much of the dolphins' extinction is caused by humans. PBR testing was done in eight bodies of water surrounding the South Island of New Zealand. These test unfortunately resulted in explaining that the time it would take to determine the populations of dolphins in these waters is much longer than expected and cannot be done until the populations are depleted, but affirms more protection needs to occur in these waters.[37]

The first marine protected area (MPA) for Hector's dolphin was designated in 1988 at Banks Peninsula, where commercial gill-netting was effectively prohibited out to 4 nmi (7.4 km; 4.6 mi) offshore and recreational gill-netting was subject to seasonal restrictions. A second MPA was designated on the west coast of the North Island in 2003. Populations continued to decline due to by-catch outside the MPAs.[12]

Additional protection was introduced in 2008, banning gill-netting within 4 nautical miles of the majority of the South Island's east and south coasts, out to 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) offshore off the South Island's west coast and extending the gillnet ban on the North Island's west coast to 7 nmi (13 km; 8.1 mi) offshore. Also, restrictions were placed on trawling in some of these areas. For further details on these regulations, see the Ministry of Fisheries website.[38] Five marine mammal sanctuaries were designated in 2008 to manage nonfishing-related threats to Hector's and Maui's dolphins.[39] Their regulations include restrictions on mining and seismic acoustic surveys. Further restrictions were introduced into Taranaki waters in 2012 and 2013 to protect Maui's dolphins.[40]

The Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission has recommended extending protection for Maui's dolphin further south to Whanganui and further offshore to 20 nautical miles from the coastline. The IUCN has recommended protecting Hector's and Maui's dolphins from gill-net and trawl fisheries, from the shoreline to the 100 m depth contour.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.